Article 19

Article 19 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan states:

“Every citizen shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression, and there shall be freedom of the press, subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam or the integrity, security or defense of Pakistan … ”

These “reasonable” restrictions have often been exploited against different groups of people such as minorities, journalists, human rights activists, atheists, homosexuals, etc. They are interpreted as a freedom to disregard others’ faiths, perceptions, sexuality, and opinions. In recent years, the enforcement of Pakistan’s blasphemy and criminal defamation laws remain a significant concern, as well as new laws to extend control over the right to freedom of expression online. Killings and attacks on journalists, media workers, and human-rights defenders remain endemic and characterized by ongoing impunity.

This story takes place in Lahore and constitutes a series of portraits of people whose way of thinking, living, and loving is obviously against the official Pakistani narrative. These images have been carefully staged to respect the safety and therefore the anonymity of the people pictured; each of them is named “Noor,” a name that means light and is used indifferently for women and men. This series is ongoing.

■

Raised in a conventional Parisian family, Marylise Vigneau developed an early taste for peeping through keyholes and climbing walls. Her Comparative Literature thesis at la Sorbonne was about cities as characters in Russian and Central- European novels; where and when the clearest narrative gets lost in a heady, haunting uncertainty. Despite her fascination with literature, over time her mode of expression has become photography. What attracts her first and foremost is how human beings are affected by borders both physical and mental, this fugitive space where an unexpected, bold and fragile act or glimpse of freedom can arise.

All images from the series Article 19

Pakistan, 2017-2018 50 x 33 cm

Digital

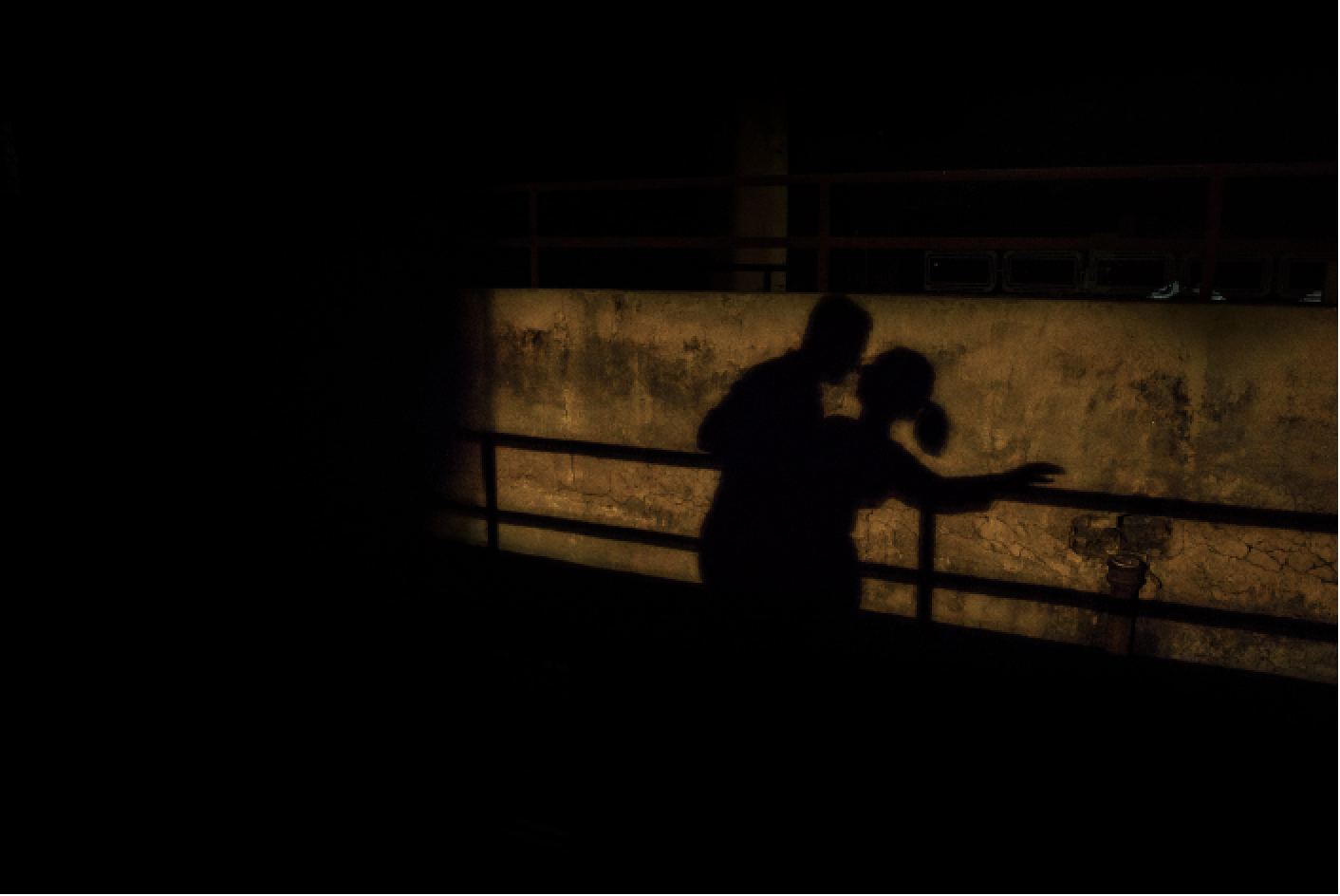

In 1977, under the military rule of late General Zia-ul-Haq, the Pakistani government implemented The Hudood Ordinances to implement Sharia law and bring Pakistani law into “conformity with the injunctions of Islam” by enforcing punishments mentioned in the Quran for Zina, which relates to adultery or extramarital fornication. It has become more frequent for young people to date and sometimes have extra-marital sexual relationships, though they need to be cautious and extremely discreet and they rarely live together outside marriage.

This picture was taken on the rooftop of a young couple that married a year ago but had been living together for the past three years. They belong to two different sects of Islam and had to fight with many prejudices and discontent from their families. They both want to leave Pakistan.

Noor grew up in a family of artists. His mother is a writer and his father was a painter. He spent his childhood surrounded by his parents’ intellectual friends and books both from the subcontinent and the west. He is the only person I encountered who did not need to fight against a conservative religious family. From childhood, he was free to be whom he wanted, a bubble within a highly restrictive society.

Nowadays he is a filmmaker, floating between a rich inner-world populated by Tarkovsky or Abbas Kiarostami and the documentary work he does for a living. He might leave Pakistan for a while in order to find more opportunities.

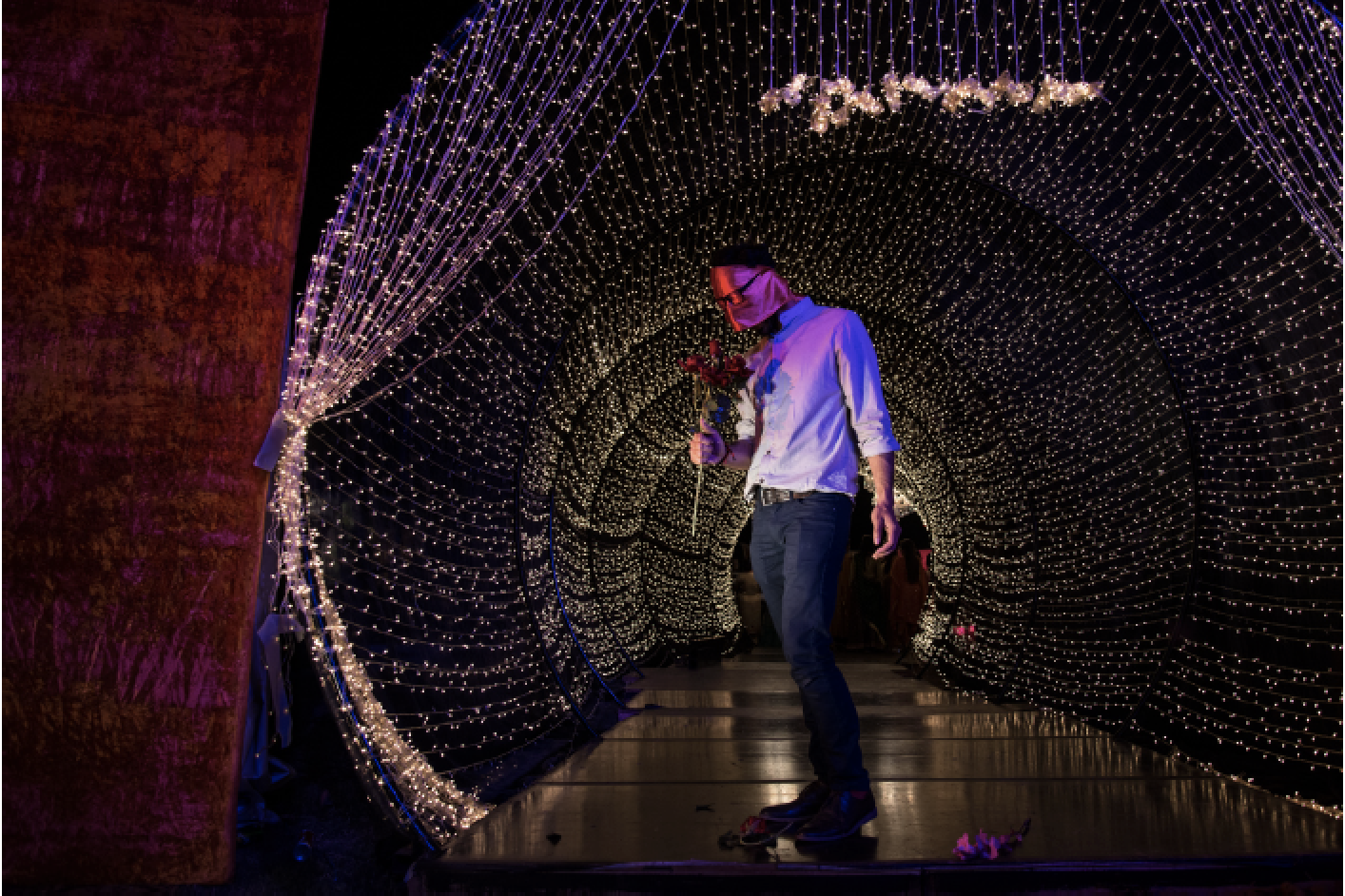

Noor is a musician in his thirties who moved to Lahore some years ago. To please his parents, he spent time in England studying something he was not interested in. He left Pakistan heartbroken and came back uncured. He almost surrendered to an arranged marriage but escaped a week before the wedding.

Earlier in his life, he had tried to force himself to believe and behave accordingly. He had even stopped playing the guitar and listening to music. All in vain since he is nowadays an atheist. He studied Marxism and was a social activist for a while but is slowly giving up because “everything is so screwed-up in this country.” Nowadays he finds shelter and comfort in his passion for music. “The only thing that matters now is how to make my career in music, that’s all. And I am loving the whole process.”

Noor, who is in her late thirties, is married to a man she had never seen before the day of her wedding. Needless to say that she was a virgin. She was utterly ignorant and very scared of everything sexual. Her defloration took a week. She is now very aware that she was lucky not to be raped during her wedding night as happens too often. Today, she loves her husband and her body. Posing naked in front of a camera was, despite her immense shyness, a celebration of life and love.

Noor is very aware that his dog Jupiter is not very popular among most muslims despite his blue eyes and white fur that make him look like the Hoors awaiting the pious and righteous in Paradise. Therefore, he makes Jupiter wear a cat mask for his safety when they venture out of the house. Cats are said to have been Muhammad’s best-loved animals.

Noor is an Ahmadi, which means that since childhood she has known that she needs to conceal this part of her identity in order to avoid verbal violence and discrimination. She understood very early that she belonged to a persecuted minority. She used to skip school on the days when the chapter about Ahmadis was studied. The Ahmadiyya sect of Islam emerged from the Sunni tradition, but most Pakistani muslims consider them non-muslims because they consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, founder of the movement, to be a prophet. Muslims consider Muhammad to be the last prophet and Ghulam Ahmad’s messianic claims are considered blasphemy. For the five million Ahmadis, religious persecution has been particularly severe and systematic in Pakistan, which is the only state to have officially declared Ahmadis as non-muslims. Pakistani laws prohibit them from identifying as muslims, and their freedom of religion has been curtailed by a series of ordinances, Acts and constitutional amendments. When applying for a Pakistani passport, Pakistanis are required to declare that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad was an impostor prophet and his followers are non-muslims. In 2008, Aamir Liaquat, a famous TV anchor, permitted a guest scholar on his show to declare Ahmadis liable to be killed due to the “blasphemous” nature of their faith. Within two days, two prominent Ahmadis were killed, one of them a physician and another a community leader.

Noor is now in her thirties and is a successful, independent, professional woman. She is proud of her freedom and enjoys reading, learning, dancing, and carnal pleasures.

She once had the opportunity to travel to a non-muslim country in South-east Asia. For the first time in her life, she could wear a skirt and feel the tenderness of the wind on her legs.

She wishes to leave Pakistan.

Noor is a gay visual artist and more recently has declared himself to be a Muslim atheist. At a young age, he lost his father, who was serving in the armed forces, to a skirmish in Baltistan, and was declared a “shaheed.” The word originates from the Quranic Arabic word meaning “witness” and is also used to denote a martyr, used as an honorific for Muslims who have died fulfilling religious duties, especially those who die waging jihad, or historically in the military expansion of Islam. Within Islamic mythology a “shaheed” transcends death. In Pakistan the word has acquired more nationalistic sentiments and is used to legitimize the deaths of its officers by portraying them as martyrs and creating a mythology around them using religion and state-sponsored propaganda. After the loss of his father, Noor was informed that there was no need to mourn his father as he was still alive, a statement which would later in his life help him come to terms with the faith he was born into.

In his teenage years, Noor became aware of his attraction towards other boys. He fell passionately in love with a much older man who would eventually lead him into a religious

cult and was the beginning of a painful romance. These experiences eventually allowed Noor to formulate a personal identity construct. Noor had once written, “there is a deep anger inside of me and a fire,” which much like the burdens of his identities, he carries inside of himself with great pride.

Noor pursued partial higher education in Europe with a thesis titled “Safety and the pursuit of the safe space,” which according to him: “of all the utopian postulations, is perhaps the most dangerous idea of all. This idea instills within us visions of a just democratic state, a life void of suffering, and eternal bliss after death, and most importantly it forces us to selflessly commit our lives towards the realization of such delusional ideas.”

Noor is back in Pakistan, where he lives with his mother who knows that he is gay and fears for his safety. In order to spare her from further anguish, he keeps his atheism to himself. He currently has no lover, “I do not wish to be somebody’s dirty little secret.”

Dancing used to be part of life in Pakistan until the rise of Zia-ul-Haq. In his policy of radical Islamization of society, he banned classical dance performances and cracked down on popular Kathak performers. The origins of Kathak, a major form of Indian dance, are attributed to the travelling bards of ancient Nothern India. Nowadays, Kathak has gone virtually underground, with only a few remaining qualified instructors and even fewer public performances.

Noor is a gorgeous woman who has decided to learn this dance. She considers herself “the most beautiful creation of God” and takes pleasure in her beauty, her body, and her sensuality.

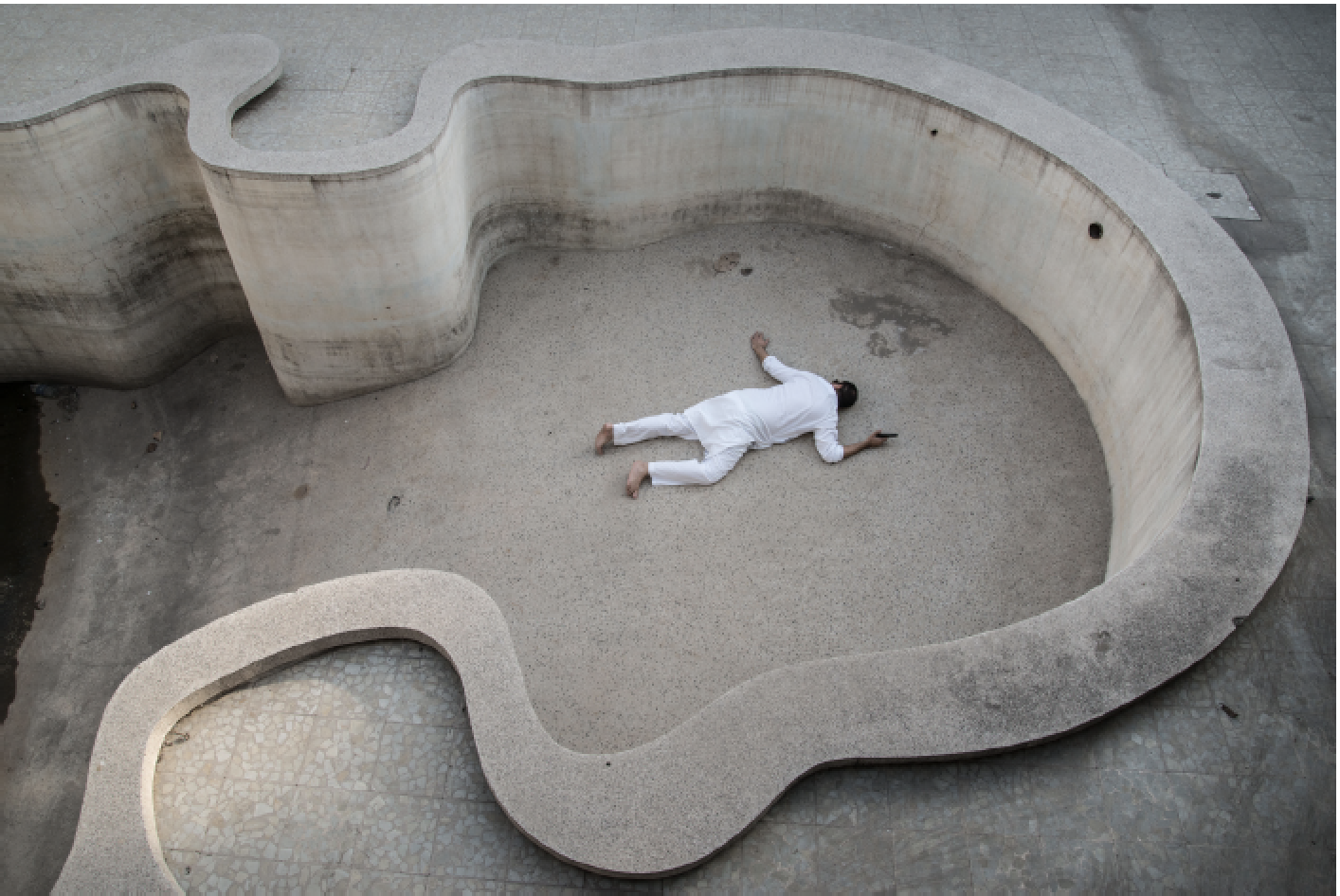

Noor is the grandson of two legendary figures of Pakistani cinema. He belongs to the Shia community but is a non-believer. He and his wife chose to give birth to their son in America so he could possess an American passport and is never stuck in Pakistan.

He poses in an empty pool in a house that is soon to be destroyed and replaced by a commercial mall. The miniature gun his in his hand once belonged to a famous British actor.

He is tired of a society that practices hypocrisy on a daily basis out of social and religious fears. “I’m afraid of your fears because it is out of fear that you act most irrationally,” he said.

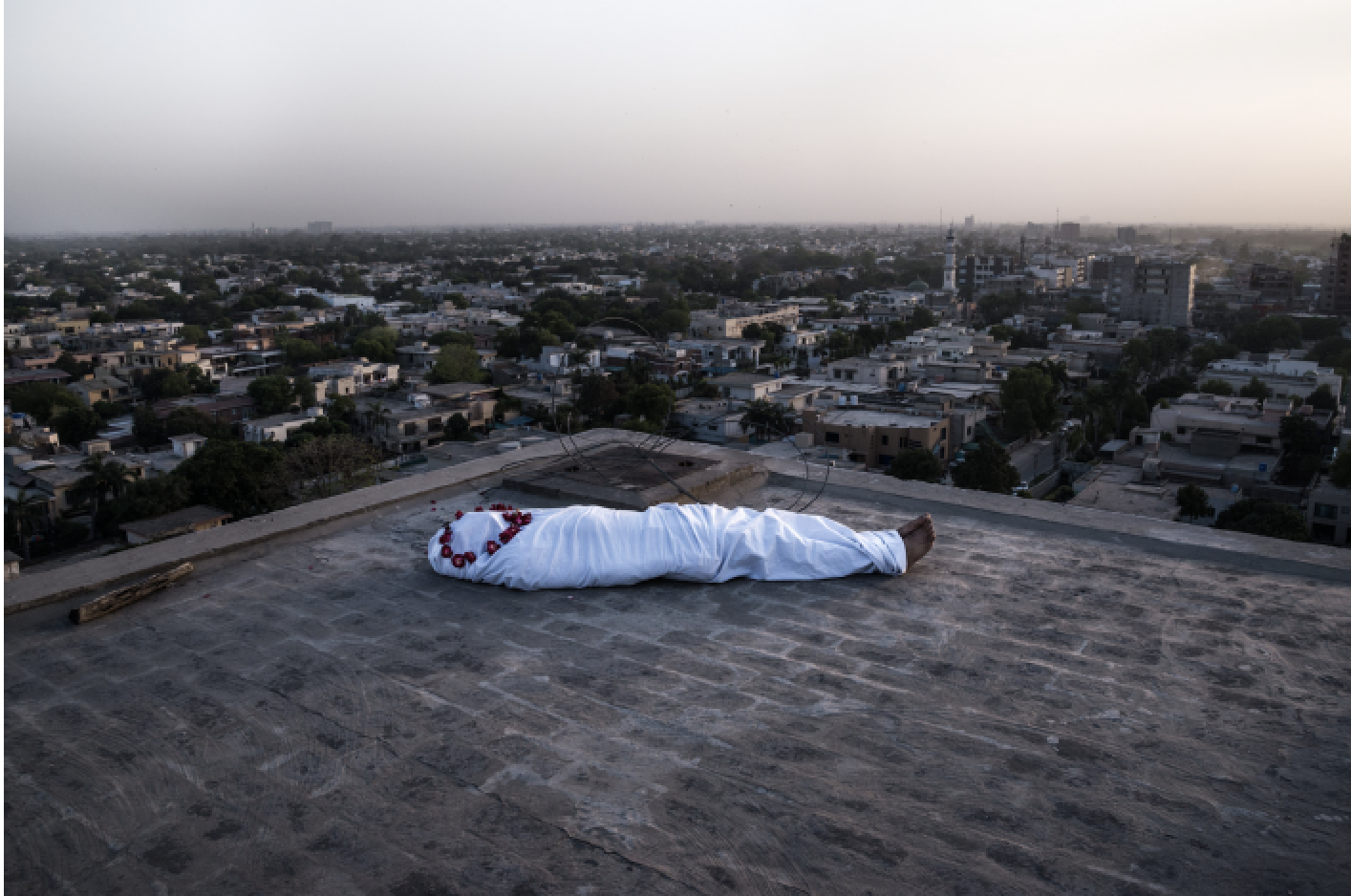

Noor was a bright, curious, sharp-eyed child. As a teenager, he found it difficult to accept the omnipresent religious narrative and began to question it. He battled and tried believing in vain. Increasingly, his vivacity, sexual urges, and observations drove him away from Islam.

Nowadays, he is an atheist without regret. He is therefore also an apostate, making him “wajib-ul-qatal” (liable to be killed) according to some extremists. He knows that announcing apostasy means inviting the risk of death— even if spared by government authorities and courts, a fanatic mob would certainly not have mercy on him. For that reason, we choose to photograph him wrapped in a shroud on the roof above a city that he loves and is sad to see being destroyed by corruption, religious intolerance, social indifference, and a kind of feudal capitalism.