The Paradox of Shahidul Alam

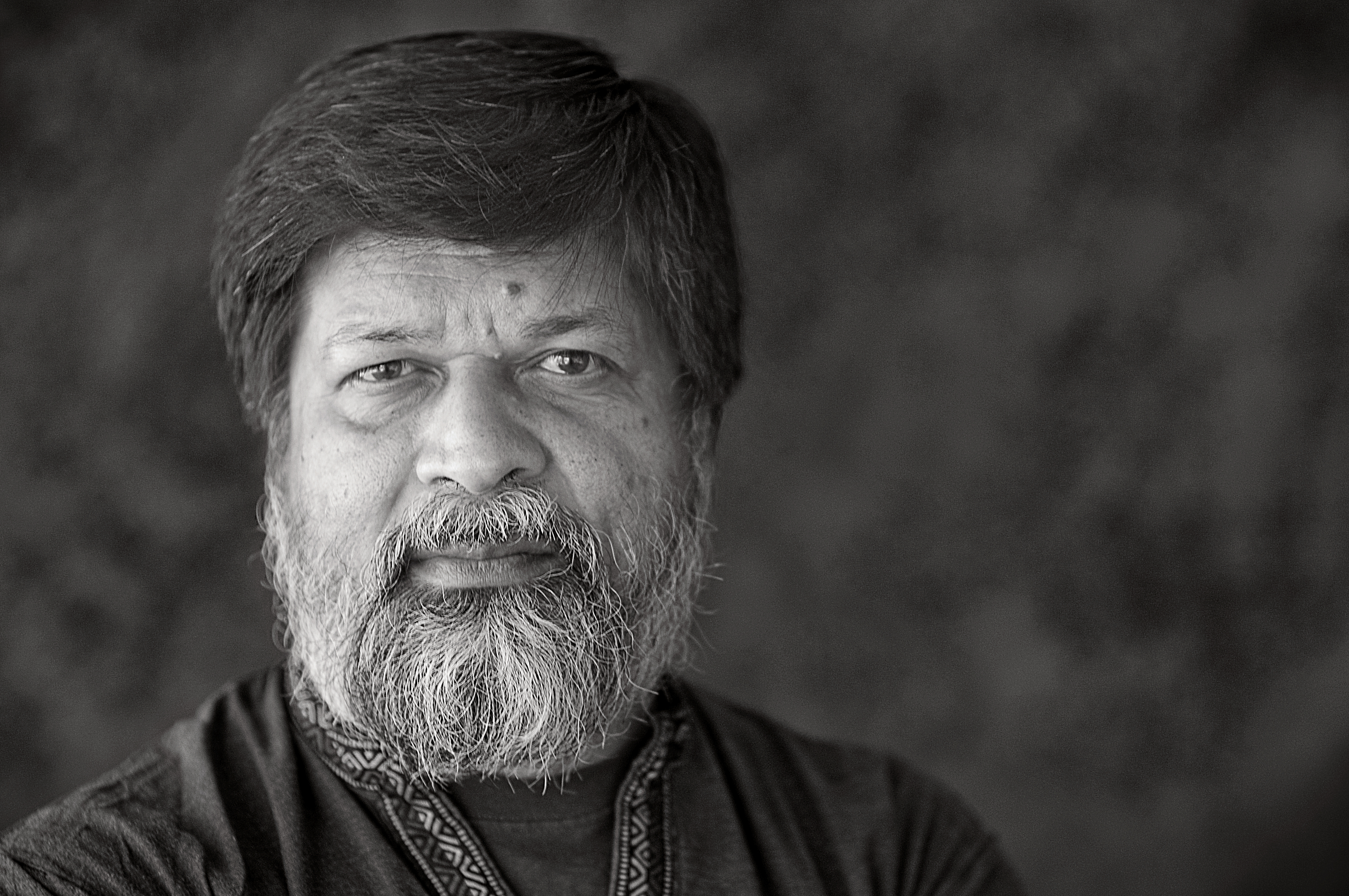

Anyone who has had the privilege of participating in Chobi Mela will have encountered Shahidul Alam as a charismatic and remarkable presence. Mysteriously energetic, he is the model public intellectual who has externalised his exceptional intellect into facilitating structures that have positioned Bangladesh at the forefront of photojournalistic practice and debate. And, while much of his, and Drik’s and Pathshala’s, work draws attention to structural features characterized by collective action or inaction, there was never any doubt that Shahidul’s individual drive, energy, vision, and generosity in enabling those around him was central to this Dhaka phenomena.

Encountering him subsequently at PhotoKathmandu (he had earlier arrived in kurta and chappals on the back of a motorbike to view an open-air exhibit), I was awed by the eloquence and scope with which he presented his work on labour migration in South and South East Asia. The political power and moral urgency of his project seemed to be literally embodied in the strength and clarity of his voice. Visually stunning, his images exemplified the potential of photography as a research method and revealed how the camera could be used to capture both singularity and also process. Moments and details of the migrant experience were suspended in wider panoramas that revealed the histories and structures of labour flow. As with all Shahidul’s images they bore the imprint of his subjects’ encounter with the man who held the camera, with his genial presence, and his indefatigable exuberance and empathy in the face of hardship.

There is no government I know that does not champion democracy and human rights in its rhetoric but also actively suppress both in its practice. It’s best to recognise that reality and work within it rather than fantasise some ideal solution that has no relevance to everyday art practice …

Still later (but in fact earlier last year, when things seemed so different) Shahidul was a source of kind wisdom and generous support during the two preliminary months I spent in Dhaka exploring current everyday photographic practices. I remember him proudly narrating his father’s role in establishing access to safe drinking water in Bangladesh and its prefiguration of Shahidul’s own dissemination of a certain kind of photographic practice as essential for social and political life. Further interaction with Drik and Pathshala sharpened my understanding of the manner in which he had built a powerhouse not as a personal monument but as an element of civil society designed to endure because of its collective strength. This resilience, this distributed and disseminated tenacity, is—to restate the paradox—the result of one man’s extraordinary impact on the world.

Christopher Pinney is Professor of Anthropology and Visual Culture at University College London. His chief interests are in commercial print culture and photography in South Asia and popular Hinduism in central India. He is currently leading the European Research Council funded project “Photodemos /Citizens of Photography” He has been awarded the Padma Shri in 2013.

Tom Hatlestad

Tom Hatlestad