Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Exhibiting South Asia

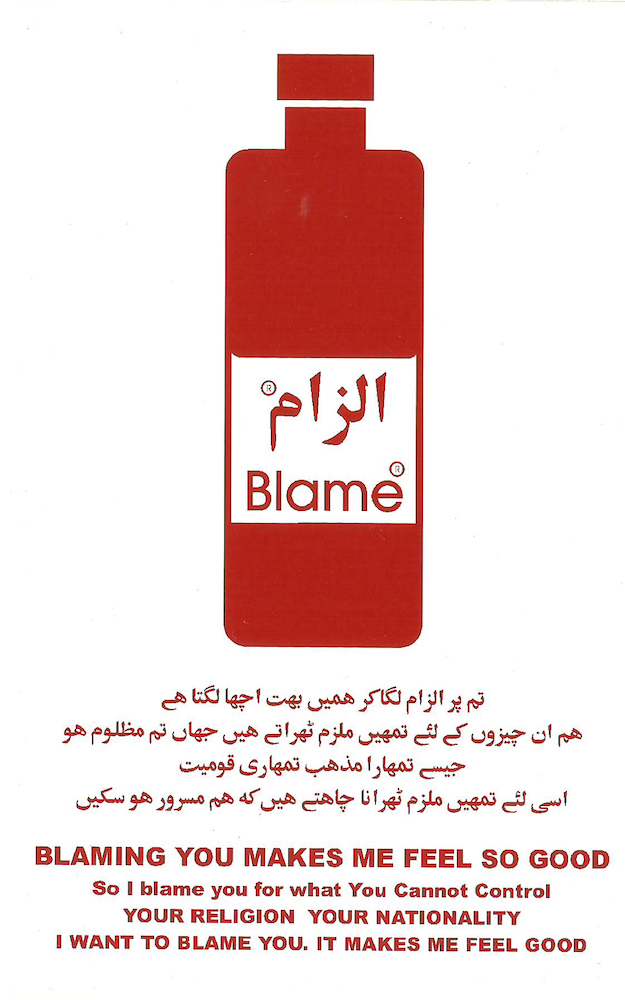

Shilpa Gupta, Aar Paar (Cross-border public project between India and Pakistan), 2002, Poster.

Image courtesy the artist.

This issue of PIX seeks to make visible a contemporary “South Asia” that transcends the normative inscription of the subcontinent as a perennially contested and divided geographical and political entity. As descriptors of regional identity, “South Asia”/ “South Asian”/ “South Asianism” have moved beyond the multiple, diverse, densely intertwined ethnic and socio-cultural commonalities anchored in or associated primarily with the Indian subcontinent, and have also pushed past a shared history of colonialism and decolonization. These descriptors today include a very large South Asian diaspora, with subcontinent-based and diasporic “South Asian” artists individually and collaboratively producing vibrant cross-disciplinary, cross-genre, experimental and intersectional work. Traditional aesthetic paradigms are being repurposed; new curatorial methods are evolving in order to project new, technology-enabled symbolic languages that are increasingly underpinned by an activist consciousness.

Given the ubiquity of image/lens-based culture today, we need to re-evaluate the discourse accreting around these shifts, with a particular focus here on the typologies emerging through new exhibition practices. Repudiating conventional, static and linear narrative formats, exhibitions are now conceived more as micro-archives or specialized caches of cultural material—dynamic nodes that may entertain through scale and spectacle, even as they instruct through the rigorous delineation of trajectory and theme. With South Asian communities as well as historical and contemporary South Asian art objects distributed across the world; there is a growing interest in contemporary voices that testify to the ever-proliferating complexities of internal/external uprooting, origin, belonging/non-belonging, genealogy, migration, exile, resettlement and other themes and trajectories revolving around the core issue of what constitutes and may be claimed, experienced and remembered as “home.”

“Location” continues to be a key variable in the “South Asian” imaginary. Steady production by artists based in South Asia, as well as by artists from the South Asian diaspora who navigate an equivocal “insider/outsider” position, has propelled South Asian art forward as an important cultural voice of the global South. Subcontinental art is now being critically acknowledged—for example, in context of the exhibition Lucid Dreams and Distant Visions (2017) at the Asia Society in New York, a reviewer asked whether the category of “South Asian art” was “useful” vis-à-vis understanding the shown works, and concluded, “I overwhelmingly say it is. To assert non-nativist contexts for art in North America is not only important today but essential in the face of a political elite that is loudly advocating the assimilation of newly arrived non-European immigrant populations.”[1]

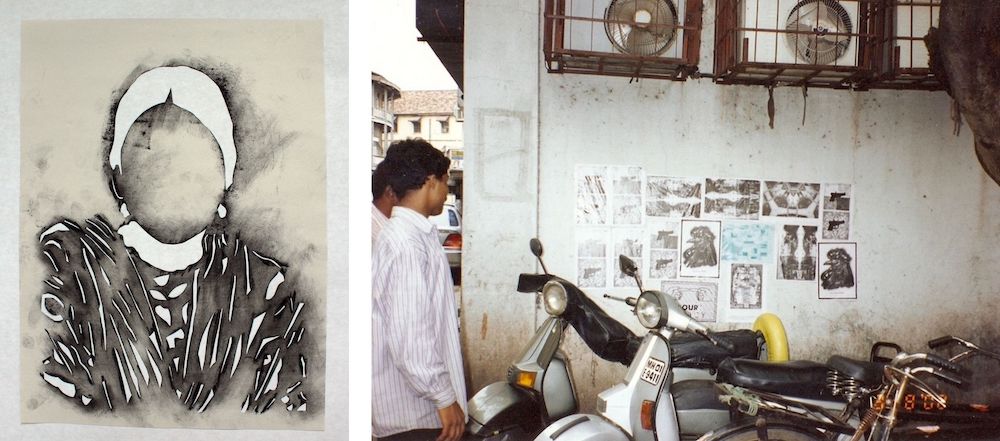

Left: Sa’dia Rehman, Surname/Nom XXXXXXXXXX Given names/Prénoms XXXXXXXXXX Sex/Sexe F, 2019, Columbus, Ohio, USA, Charcoal on hand-cut newsprint. Image courtesy the artist.

Right: Shilpa Gupta, Aar Paar (Cross-border public project between India and Pakistan), 2002, Poster.

Image courtesy the artist.

Globally, exhibitions that project principles of pluralism and inclusion, even while adhering to principles of historicity, are now using new media as a matter of course. It allows them to take advantage of digital technology in order to subsume boundaries and collapse time and space. This is exemplified in two exhibitions from an earlier decade during which the newly-arrived new media technology began definitively widening and altering the orbit of cultural production. The Aar Paar Project (2002), co-curated by Huma Mulji in Pakistan and Shilpa Gupta in India, brought together ten artists from across South Asia. Each artist was asked to work in a single colour, and the resulting images were emailed across borders to be printed in each other’s country and simultaneously exhibited in Karachi and Mumbai.[2] Six Degrees of Separation: Chaos, Congruence and Colaboration in South Asia (2008), organized by the Britto Arts Trust (Dhaka), the Indian Artists Association (New Delhi), Theertha International Artists’ Collective (Colombo) and Vasl Artists’ Collective (Karachi), presented over forty-five projects from across the region. The exhibition saw five editions opening simultaneously in Karachi, Colombo, Kathmandu, Dhaka and Delhi in the first week of September that year. Refuting the assumption that so much is edited, deleted, stereotyped, censored, downplayed, segregated, or simply discarded in our conversations and interactions when we try to understand each other’s “South Asian” subjectivities, both projects pivoted around envisioning how “Other” audiences might respond to culturally specific representations.[3] Both the projects also reflected on the potential of digital image-practices to radically remap “South Asia” through aesthetic modalities, i.e., to generate an open space for cross-border artistic collaboration.

Such exhibitions enable us to imaginatively recalibrate the fraught, politically polarized, militarized cartography of “South Asia” through the contemporary reframing of established and/or occluded social histories/micro-histories. This process has also been given fresh impetus through an expanded pedagogy—that includes fields such as digital anthropology—and is emphasized in the new scholarship flourishing in South Asian area studies. University departments across the world are now actively engaged in formulating new paradigms and definitions of “South Asia,” “South Asian” and “South Asianism.” For instance, cross-referential theorization infuses the work of scholars such as Professor Parvati Nair[4] and Professor Bakirathi Mani[5] who examine how cultural and media production/consumption is mediated between the “East” and the “West” and transformed through diasporic perspectives that are simultaneously “outside-in” and “inside-out.” The new scholarship also traces the rise in arts activism in South Asia, probing the formation and negotiation of sub-continental nationhood. It presents a counter-narrative to the homogenizing, majoritarian claims pivoting around issues of “legitimate” citizenship—supremacist rhetoric that is stridently deployed all over our region to inflict unconscionable trauma on vulnerable populations accused of being insufficiently “national.”

There is also an increased focus on the expanding significance, role and contribution of cultural institutions, community arts spaces, arts management and arts critique in South Asia. Diverse initiatives and individuals—variously influential in their local and/or national spheres—are essential to the evolving discourse around regional histories of representation, a discourse that logically extends from South Asia to the rest of the global South. These include, among others, Nepali journalist/activist Kanak Mani Dixit, co-founder of the magazine Himal Southasian;[6] Bhutanese filmmaker Dechen Roder and the Voluntary Artists Studio Thimphu (VAST);[7] as well as practitioner-based formations such as The Confluence Collective (India)[8] and the DRUM Archive (South Africa). [9] Many artists, even outside this issue—for instance, Sa’dia Rehman, Allan deSouza, Schandra Singh, Samanta Batra Mehta, Rina Banerjee, Kounteya Sinha and Shoma Basu[10]—have engaged with South Asian themes and trajectories. “South Asianism” as discussed by social scientists such as Ashis Nandy, Arjun Guneratne and Anita Weiss makes us think once more about the current moment of hyper-visibility.[11]

Mahbubur Rahman. All we are saying is give peace a chance. The work was done for the exhibition Six Degrees of Separation: Chaos, Congruence and Collaboration in South Asia, a South Asian Network show by Khoj and Anant Art Gallery, New Delhi. “The line was taken from John Lennon’s famous song. The outfit on the right side was made out of leather from used army boots. The outfit on the left was made of the fabric used for army camouflage. I embroidered it with floral designs. During the opening, I did a performance wearing that outfit and the video of the performance was projected on the measurement tapes hanging from the middle of the ceiling.” 2008, Measurement tapes, army boots, camouflage fabric, digital video footage of performance on the spot. Image courtesy the artist.

This issue of PIX urges us to scrutinize “South Asian” arts production in terms of the multiple meanings of the “real,” the “authentic” and the “true,” as well as in terms of the dialectic of being/becoming. Our symbiotic imaginaries insist that whatever be “our” location, identity or affiliation, within the subcontinent or outside it, through our art “we” will continue to encounter ourselves, to hold the mirror up to ourselves, and to ask ourselves whether it is even possible to fully understand who/what/where we “South Asians” actually are.

Allan deSouza, Indians, from the series The World Series, Alcatraz, California, USA, 2011, Digital photograph. Image courtesy the artist and Talwar Gallery, New York and New Delhi.

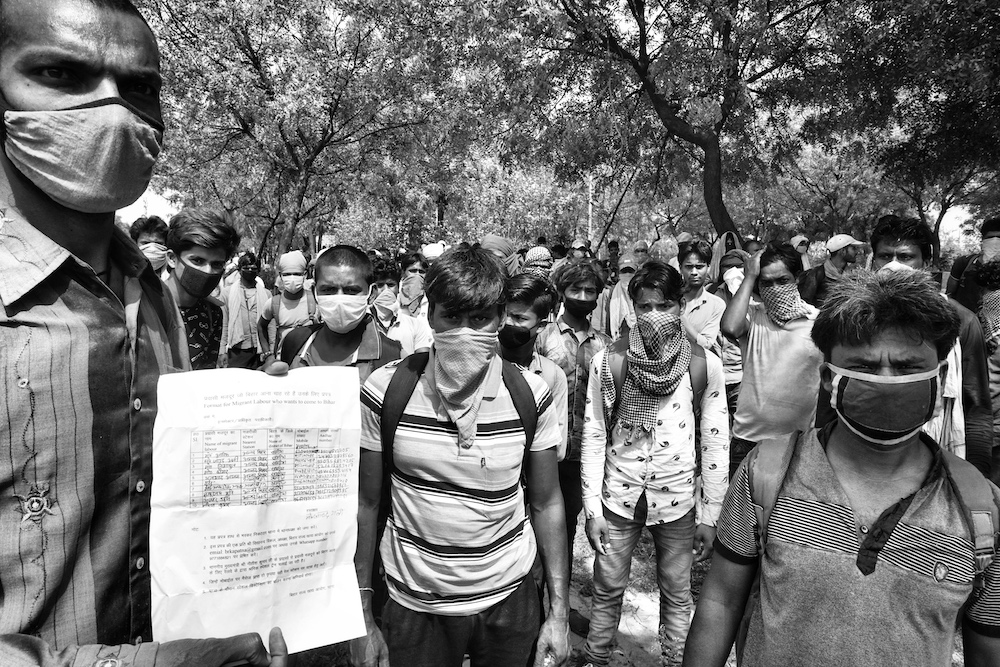

Shome Basu, Lockdown Migrant Workers. “Md. Arif has filled the form but the District administration is not taking any heed, he says. There is no information about trains from Anand Vihar in New Delhi, so they are confused.” Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India, 2020, Digital photograph. Image courtesy the artist and The Wire.

NOTES:

1. Hrag Vartanian, “What Does It Mean to Make Art in the South Asian Diaspora?” Hyperallergic, 4 August 2017. Source: https://hyperallergic.com/391578/what-does-it-mean-to-make-art-in-the-south-asian-diaspora/

2. “Aar Paar was a project in which artists from Karachi and Mumbai, made work which was swapped between the two cities and shown in public spaces: roadside eating places, paan shops, etc. The idea of intervening in the city was to encourage an alternative audience, extend viewership of art, to not exclusively an ‘art’ audience, but incidental viewing and sharing of work by artists, in places where spontaneous interaction between people occurs.” Source: https://aarpaar2.tripod.com/

3. Visit: https://khojworkshop.org/programme/six-degrees-of-separation-chaos-congruence-collaboration/ and https://www.anantart.com/publications/75-six-degrees-of-separation-chaos-congruence-collaboration-group-exhibition/

4. Nair is a Professor of Hispanic, Cultural and Migration Studies at Queen Mary, University of London.

5. Mani is a Professor in the Department of English Literature at Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania.

6. Visit: https://www.himalmag.com/

7. Valentina Vitali, “Interview with Dechen Roder,” in BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies, Vol. 11, Issue 1, November 2020, pp. 96-100. Also, visit: https://www.bhutanfilmfestival.bt/

8. Visit: https://www.theconfluencecollective.com/

9. Lesley Cowling, “Echoes of an African Drum: The Lost Literary Journalism of 1950s South Africa,” in Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2015, pp. 9-32. Also, visit: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/drum-magazine

10. Visit: http://www.sadiarehman.com/, https://allandesouza.com/, https://dhoomimalgallery.com/artist_info.php?id=MjA5, https://samantabatramehta.com/

11. Visit: https://rinabanerjee.com/, https://www.asian-voice.com/Opinion/Columnists/Keith-Vaz/Kounteya-Sinha, https://idronline.org/contributor/shome-basu/, https://thewire.in/author/sbasu

12. Ashis Nandy, “The Idea of South Asia: A Personal Note on Post-Bandung Blues,” in Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Vol. 6, No. 4, 2005, pp. 541. Also, see: Arjun Guneratne and Anita Weiss, eds., Pathways to Power: The Domestic Politics of South Asia. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014