Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Introduction

Bakirathi Mani, Covers of Aspiring to Home (2012) and Unseeing Empire (2020).

Passages offers us photographs that appear uncannily familiar, as if they capture relatives distant and unknown. Plucked out of national and personal archives, these images acquire new lives in the form of photobooks, or on a humble paper bag. Some photographs emerge out of the domestic spaces of a bedroom in New York or Montreal; others come to us from the deep waters of the Persian Gulf, or from the vast desert outback of Australia, or from university campuses in South Africa. Taken in the form of documentary and street style photography, paying homage to sojourners in the nineteenth-century and to the vitality of youth communities now, each of these photographic works remaps our understanding of the relation between South Asia and its diasporas. In the artists’ hands, the photograph becomes at once an archival record of immigration from the subcontinent to Africa, the Americas, Europe and Australia, and a quotidian document of everyday life.

What strikes me is how many of the artists operate as archivists, as curators and as truth-tellers. By selecting images from family albums to recreate as contemporary portraits, or by reproducing newspaper articles that decry South Asian immigration, or by documenting their protests against undemocratic regimes in Bangladesh and in India, these artists deploy the photograph in unexpected ways. We know that the photograph is a medium of duplication, yet what we see through these artworks is not duplicity but something that brings us closer to the truth.

Passages shows us the ties that bind the subcontinent’s imperial pasts to its postcolonial present, the ways in which the photograph links together the private life of the family with the public life of the state. The photographs visualize the complex routes taken by migrants from South Asia to Dubai, Durban and Rio de Janeiro in the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries; as well as the movement of refugees from occupied Tibet to Kalimpong, from Pakistan to India, and from Myanmar to Delhi in our present time. However, these photographs do more than document. Through the artists’ own intimate relation to these images, the photograph becomes a mirror object—a way for us, as viewers, to catch a glimpse of ourselves.

What do we feel when we look at these photographs—especially those of us who are in and of diaspora? Feminist and queer scholars have argued for “feeling” as well as “thinking” photography, arguing that “…the rubric of feeling promises tolink the older photographic criticism’s attention to power and historical materialism with new questions concerning racial formation, colonialism, postindustrial economies, gender, and queer counterpublics.”¹ To attend to our feelings in relation to the photograph requires us to step closer to the histories—personal, familial, national, imperial—that shape how these images came to be and what they have come to mean. The feelings of closeness and distance, belonging and alienation, that we craft in relation to the image enables us to understand why photographs are so dear to us, and why—as diasporic artists and as diasporic viewers—we so often desire to identify with the images we see.

“A box of your photographs found its way to The Confluence Collective to become, unwillingly, a part of their archive,” writes Ruchika Gurung. “I found myself placing your image at the centre of the table while the other photographs formed concentric circles moving away from you.” Dear Kesang, Gurung and The Confluence Collective’s project, illuminates the artist’s desire to come closer to the photographic subject of an unknown archive—a box of photos identified only by the brief appellations on the back of each image. Though these are photographs of a stranger, Gurung finds herself engaging in an imagined dialogue with Kesang, the subject of several of these images. Kesang, who appears to be the daughter of Tibetan refugees, is photographed in Northeast India, Puducherry and in Switzerland; her father is photographed in Beijing and Kolkata. These faded, sepia-toned images come to map not only the trajectories of Kesang’s life, but also Gurung’s own. Like Gurung, who has migrated from Kalimpong to England to Mumbai; Kesang creates new communities and embodies different identities: she is photographed in a chuba, in an Anglican school uniform, in a pair of pants. The relation that Gurung establishes with Kesang—knowing that she is not Kesang, but that Kesang might be like her—is what I have described elsewhere as “diasporic mimesis,” the process of creating a powerful relation of identity between one diasporic subject and the visual representation of another.²

Similarly, in his project Telia, the photographer Yask Desai finds himself compelled by a portrait image of an Indian man in early twentieth-century Australia. This man’s face is reproduced on anti-racism posters across public spaces in Sydney, only to be ripped into and defaced. Moving in concentriccircles from this single image, Desai discovers a larger community of South Asian men who emigrated from colonial India to sell trinkets and other goods across the continent, and whose employment in Australia was central to the financial stability of their families at home. Rendered in the Australian national archives as the “‘Indian Hawker’ nuisance” and buried under the category of “Stranger” in local cemeteries, men like Monga Khan, Khawaja Bux and Ali Buc come to life through the passport and portrait images that Desai reproduces, as well as his own photographs of their descendants in Sydney, Birmingham and Punjab. In Telia, the photograph operates on multiple registers: as an archival object and as an object of mourning, as a pedagogical text and as a political one. By animating through photography the lives of men who were

“…living, working and moving in the shadows of two empires,”³ including, in this case, the British empire and the settler-colonial ethos of the “White Australia” policy, Desai—like Gurung—brings us closer to those men, women and children whose diasporic trajectories preceded our own.

Such intense relations of feeling—coming close to the photographic object, and identifying with the subject of the photograph as if they are our own kin—are central to the work of several artists in this issue. Cheryl Mukherji and Zinnia Naqvi both create self-portraits in relation to women they are already deeply familiar with. In Mukherji’s case, her mother; and in Naqvi’s, her grandmother. In creating new portraits that reproduce—in whole or in part—photographs of the women they claim kinship with, Mukherji and Naqvi remap feminist genealogies that tie mother to daughter, women to nation, and gender to sexuality. Priya Kambli takes an old photograph of her mother in Mumbai and duplicates it in a portrait of her own daughter in Missouri. As we see this image of Kambli’s daughter, we also see literally reflected in her eyes the photograph of her grandmother: a woman she has never met, a grandmother who died before she was born. Rajat Dey takes his family photographs and through digital collage creates a sense memory of his grandparents’ migration from East Pakistan after the riots of 1964 as well as the life that they built subsequently in Kolkata. Like the ventriloquist in one of Dey’s images, these composite photographs speak for a history that we cannot recover in full.

In the absence of established narratives of migration, the family photo becomes a primary archive of diasporic history and memory. Vijai Patchineelam has curated, compiled and produced a book of his father Sambasiva Rao’s photographs, which map his journeys between Andhra Pradesh and Rio de Janeiro after receiving a Minolta camera in 1972. Though a trained scientist, Sambasiva Rao becomes known to us through this book as an artist; likewise, though Vijai Patchineelam is already established as an artist, here he has become an archivist. The images compiled in this photobook not only navigate the complex passage between Asia and Latin America; they also document the changing technology of photographic film, the colour more saturated in some images than in others. Sambasiva Rao photographs family and strangers in India and in Brazil; he turns the same loving eye to his scientific equipment, whether on boats or in the laboratory. Whether capturing a severed head of fish or a molten face of rock, Rao’s camera moves backwards, forwards and sideways. Patchineelam’s book creates a different temporality of migration: another way of knowing and feeling what it means to live in diaspora.

In Gurkha Sons, a project by Nina Manandhar, we see what it means to create diasporic identities and communities in the present. Manandhar photographs what she describes as a “new generation of British-Nepalis,” the children and grandchildren of Gurkhas, whose renowned military discipline was central to the expansion of the British empire. The Brigade of Gurkhas—which once fought for the British East India Company and subsequently for the British Indian Army—are a 4,000 strong regiment of the British Army today. In Manandhar’s images, we see young men revelling in their masculinity: in the cut of their hair and the swagger of their clothes, the expansive flourish of their tattoos and flashes of gold jewellery. Also based in Britain, Mathushaa Sagthidas’ work, ஒரு தீவிலிரு௺து ஒரு நகரம (Oru theevilirinthu oru nagaram; A City away from an Island)explores what it means to create and embody a feminist identity as Tamil Sri Lankan and as British: in the jewellery that adorns her subjects’ hair, wrists, ears and thighs; in their gaze, at once directed towards the viewer and guarding against them; in the collective solidarity that these women forge with each other.

As diasporic artists create photographic works that explore the ambivalent relation between nationhood and citizenship, they also turn to the passport photograph as a testimony of migration. The passport photo becomes a means for viewers to travel—not in space, but in time. The passport is at once a document of surveillance, a means for the government to monitor its citizens. At the same time, it is a prized personal object that signifies mobility. For those who emigrated out of South Asia before 1947, the passport is also a document of empire. The passport identifies who the traveller is, where they can move, how long they can stay. It is a time stamp and a record. In itself, the passport is an archival document, one that orients the trajectories of diaspora. But what kind of proof does the passport provide? What assurances can the passport photo make of our own belonging?

In Unsettled Identities, Anuj Arora photographs Rohingyas living and working in densely populated refugee camps across Delhi. In one image, we see the passport photograph of a woman named Shaheeda Begum, alongside a family photo. Her passport, in this instance, was mobilized by the military junta in Myanmar as proof of the Rohingyas’ illegitimacy. It functioned not as a testament to belonging, but as a record of the racial and religious discrimination that Shaheeda endures, and that resulted in her exile. Travelling nearly a century backwards, Harsha Pandav scans her great-grandfather’s passport pages. The page on the right has a handwritten inscription that notes his dwelling in Dubai, though the passport is endorsed and stamped by the “Commissioner in Sind.” Issued in Karachi on 22 February 1922, the passport proclaims its owner as a “British subject.” Below his name, we see how empire works to surveil its colonial subjects: the passport pages note the size of Pandav’s great-grandfather’s forehead, nose, mouth and chin; his height and weight; the colour of his hair, his complexion and face. We recognize here that the passport is more than a document of transnational mobility; it is also a visual narrative of eugenics, the colonial racial ideology that determined who is human and who is not. These traces of classification persist into the present in Arpita Shah’s Nalini. In one image, a passport photograph documents her great-grandmother, born in 1915. The date stamped on this passport, clearly issued by the postcolonial Indian government, is obscured by a stem of bougainvillea, a flower introduced during British rule of the subcontinent. Shah’s great-grandmother signs her name under her own photo, but we note that under the category “occupation,” the government emissary has transcribed “nil.” For women, whose labour—both reproductive and domestic—remains unrecognized, the absence of an occupation means that their subjectivity is always tenuous, always contingent on the patriarchal structures of the family and the state. On this passport, the earlier measurements of face, chin, mouth and nose are eliminated, replaced by the subject’s height and a curiously intimate description of her hair color: “black & greying.”

I write this as a woman who also has black and greying hair, a woman born some sixty years after Shah’s great-grandmother. I write as a woman who has held seven Indian passports, from birth till age forty-five, even though I have lived in India for just two years and was raised in Japan thereafter. In my family, I am the first woman to have an occupation listed under my name. I now hold one American passport, issued just before the outset of the pandemic. Its pages are wiped clean of my past travels, and there is only one identifying photograph, saturated with colour. In reading this new document of belonging, I am rendered as a citizen without a past. What stories can come out of the seven passport photos locked away in a filing cabinet, and from a new passport awaiting its first journey? What narratives of South Asia and its diasporas can we map out in the twenty-first-century?

Through the rigour and care that they direct towards the photographic image, the artists in Passages orient us towards these futures.

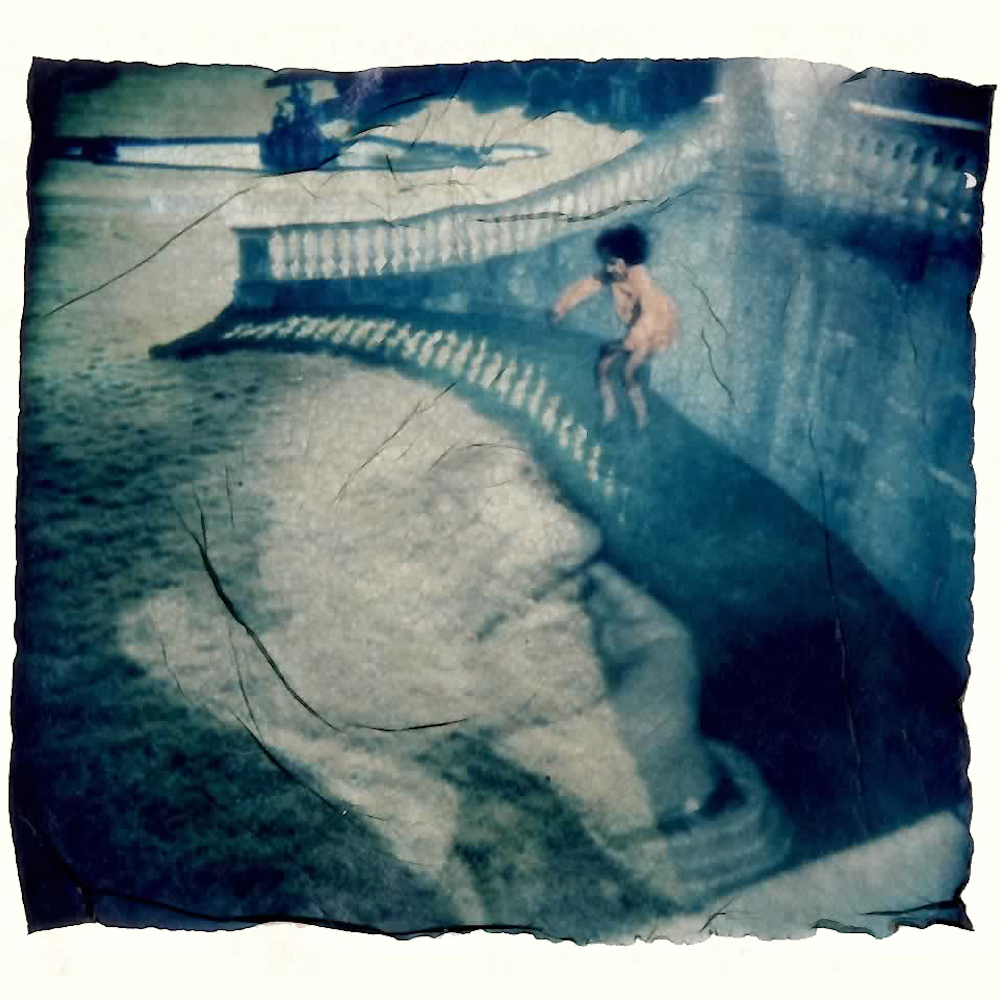

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, Dad & Me, 1999, from Fabricated Memories, 1997-2000, Single image, Polaroid emulsion transfer on paper in handmade artist book with metal box. Image courtesy the artist and sepiaEYE, NYC.

Bakirathi Mani is a Professor in the Department of English Literature and Coordinator of the Gender and Sexuality Studies Program at Swarthmore College. A scholar of South Asian diasporic public culture, she is the author of Unseeing Empire: Photography, Representation, South Asian America (Duke University Press, 2020) and Aspiring to Home: South Asians in America (Stanford University Press, 2012).

NOTES:

1. Elspeth Brown and Thy Phu, “Introduction,” in Brown and Phu, eds. Feeling Photography. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014, pp. 7-8.

2. Bakirathi Mani, Unseeing Empire: Photography, Representation, South Asian America. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020, p. 5.

3. Vivek Bald, Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013, p. 16.