Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Looking to Southeast Asia

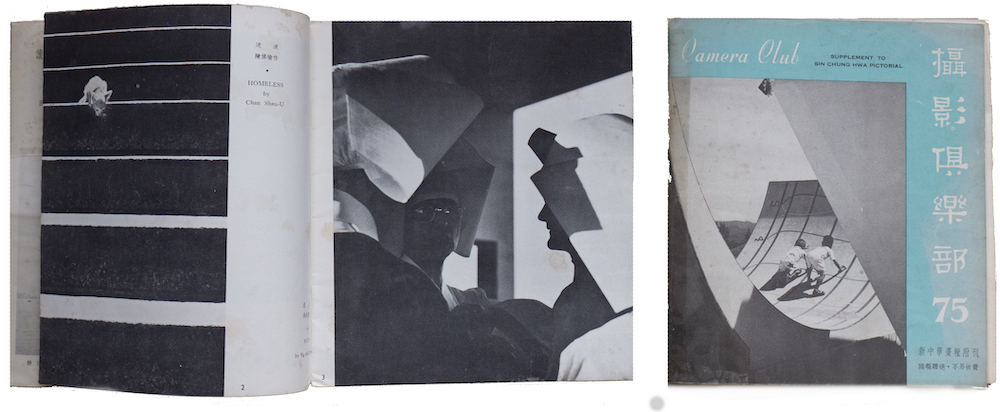

Published out of Hong Kong, these are copies of Camera Club, which was in existence from 1956 to 1960. It came as a free supplement to the popular Sin Chung Hwa Pictorial, a pictorial periodical that covered the progress of communist China. It was reported that its inaugural issue in 1952 was already widely distributed across parts of Southeast Asia. Around the mid-1950s, the pictorial started to include reports on leisurely pursuits like music and gardening to tone down its pro-Beijing political slant. From its 50th issue onwards, it included the Camera Club supplement. The team behind the supplement would go on to publish Photo Pictorial.

Zhuang Wubin, author of Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey, attempts to map the emergence of new narratives of photography from the region, beginning in the colonial era. His writing attempts to show how the transfer of photographic technology occurred between visiting practitioners and local photographers, especially in the countries of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, Philippines and Vietnam. Largely focused on the post-Second World War era, he draws upon the wider relationship between art and photography, and offers an entry point into the cultural and social practices of the region, as well as a prism into the personal desires and creative decisions of its practitioners.

In this interview he goes further to speak about common strands in photography, in the broader Asian region, with a focus on pictorialism and “salon photography.”

Rahaab Allana: When did you start writing about photography in Southeast Asia?

Zhuang Wubin: I started writing in 2004. I was primarily interested in what was happening in Southeast Asia, though I did not really think of it as a regional project at the time. However, as I travelled more, I developed a stronger affinity with the region. Initially, I was collecting interviews and publishing them. Then I became much more systematic in 2008.

In 2010, I received a research grant from the Prince Claus Fund which allowed me to sit down and start doing literature review. That was when the possibility of doing a book emerged. The initial manuscript sat with me for a bit before somebody introduced me to the National University of Singapore Press. After they expressed their interest, I started rewriting the manuscript. Many things were changing rapidly on the ground in places like Cambodia and Myanmar, especially during 2012 and 2013.

RA: It seems like a transnational project, so what were the connecting lines around people’s commitment to social issues?

ZW: At that time, I was more interested in mapping what had happened across the region. The book, Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey, is organized by chapters dedicated to the different nations. I tried not to reduce, for instance, the overall development in Thailand to that of Bangkok. In Indonesia’s case, other than Jakarta, I was also interested in the developments in Bandung, Yogyakarta and East Java.

In the book, I tried to give a preliminary sense of what transpired from the colonial period until the contemporary. I was always conscious that I was writing for the photographers in Malaysia, Philippines or Thailand. When I was doing fieldwork, there were very few writers who were interested in trying to piece together a narrative of the different photographic practices in Indonesia, for instance. So I found myself trying to represent the voices and narratives of local photographers.

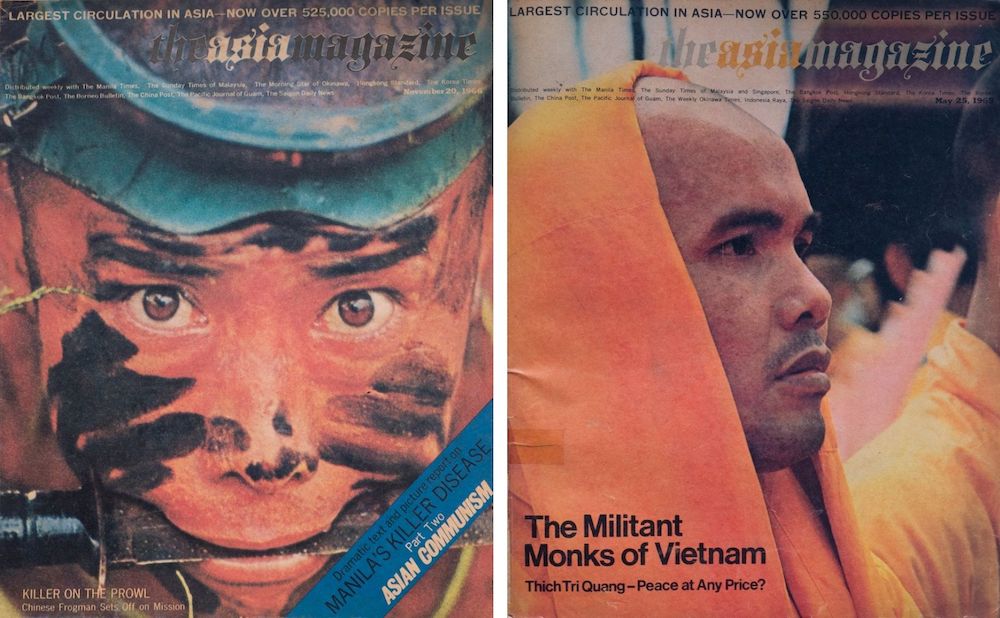

Asia Magazine was founded in 1961 by Norman Soong. It was headquartered in Hong Kong and printed initially in Tokyo.

RA: You referenced particular tropes that came into the publication of certain books from North and South Vietnam. Pictorialism is one of them, salon photography another. Of course, those tie in very closely with developments that were similarly taking place in India. Can we think of this in terms of a common media history?

ZW: In our work, we like to use labels like “documentary photography” or “modernist photography” as a kind of shorthand. However, from a basic standpoint, I am also wary of using all these labels, as they have been appropriated from elsewhere.

We can use the form of the pictorial periodicals in Southeast Asia as an example. This is a topic about which I am trying to find out more. When individuals and publishers started putting out such publications around the 1930s in the region that would become Southeast Asia, it would be problematic to assume that the form of the periodical was seeded from the metropole directly to the colony. The embedding of the idea of the pictorial periodical was much more circuitous.

For instance, those who put out pictorial periodicals in Shanghai during the early decades of the twentieth-century looked at German and Japanese periodicals as their references. It is very likely that Shanghai periodicals, in turn, served as an important reference point for those in Malaya and Singapore bringing out similar publications in the 1930s.

We can also think about the practice of photojournalism. With what we quite naturally call “photojournalism” or “documentary photography,” the question arises—how were these terms and practices initially embedded (translated and refracted) locally across the region? How were they translated into bahasa Indonesia, Vietnamese or Chinese? All these routes of embedding these terms and practices would have implications on how photojournalism or documentary photography would be practised at different points in time.

I am also interested in salon photography. I prefer to use the term “salon photography” instead of pictorialism, partly to point out its longstanding connection to the ethnic Chinese photographers across Southeast Asia. That connection started in the first decades of the twentieth-century. After the end of the Second World War, the number of ethnic Chinese photographers in Southeast Asia who participated in salon photography increased rapidly. For these photographers, the practice was popularized through the Chinese language. If you look at pictorialism in an Asian context, you will see that in places where there are significant Chinese communities, salon photography seems to live on longer. I am not saying that there is no salon photography in Bangladesh or India. However, in many of these postcolonial spaces in Asia where you see a thriving practice of salon photography, it is likely that Chinese photographers are at least partially responsible for sustaining it.

In Singapore, the government presents an award called the Cultural Medallion, which is the highest honour conferred by the state to art practitioners. It used to be organized through the different artforms. Every single photographer who has been awarded the Cultural Medallion has been and, in many cases, continues to be associated with the praxis of salon photography, through his (the salon photographer “recognized” in Singapore is typically male) membership in the amateur photo clubs. In Thailand, they have something similar called the National Artist Award. To the best of my knowledge, most, if not all, of the photographers who have received the accolade have had connections to salon photography. Many of them are/were of Chinese descent.

I think it is problematic to assume that the imprint of salon photography has been relegated to the past. In Karen Strassler’s work, she believes that salon photography has been mobilized by the Indonesian state to create a national iconography during decolonization, a kind of national imaginary that is still relevant today.

In the Republic of Vietnam, salon photography was practised by Vietnamese and Chinese photographers. After 1975, we still see the spectre of salon photography beneath the veneer of the Vietnamese Association of Photographic Artists (VAPA), as it is directly affiliated with Fédération Internationale de l’Art Photographique (FIAP / The International Federation of Photographic Art). Even though VAPA has had its origins in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the communist north, it continues to operate, post reunification, through the praxis of salon photography. On the surface, its practitioners might engage in what looks like apolitical work, precisely because of VAPA’s political connection to the state.

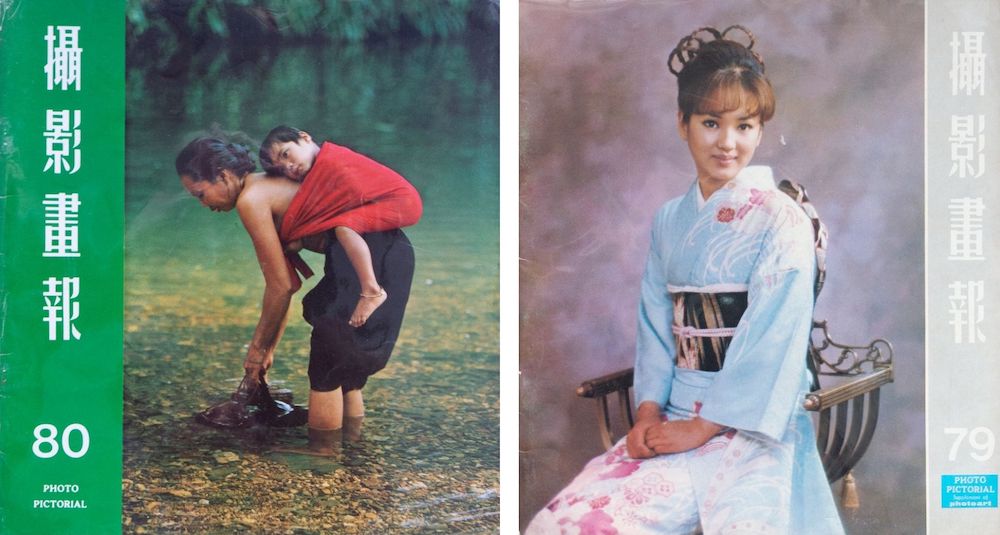

These are copies of the iconic Photo Pictorial, published out of Hong Kong from 1964 to 2005. Its initial focus was on salon photography and photography as a hobby. The magazine also put forth an aestheticized form of street photography. It was popular amongst Chinese-speaking readers in Southeast Asia.

RA: How does one view Southeast Asia’s predicament within current media dissemination?

ZW: I do not mark time this way anymore. Somehow, I feel that a lot of what is happening in the contemporary moment is really a continuation of our past. For instance, when we talk about this massive circulation of images on Instagram, we are talking as though this is something that is very new. I think the only real difference is the speed and reach of the circulation of images. However, speed is always relative. When cinema became available to the masses across part of the region in the early decades of the twentieth-century, it was, to them, an acceleration of speed, a traversing of time.

When we revisit spaces like Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Batavia, Rangoon and Calcutta before the Second World War, there was already a kind of cosmopolitan culture circulating through radio, gramophone, cinema, photography and the popular periodicals, among others. Of course, I am not suggesting that these places were cosmopolitan in the same way or to the same degree. In any case, the big marker of change with the onset of digital technology is a far deeper penetration of these technologies (including photography) into the masses. In this sense, I am reluctant to say that the circulation of images today is much more global than it was in the past. This is because I am not sure that it is historically or experientially accurate to say so, especially for people who were in Rangoon, Madras, Bangkok or Batavia then.

The other issue concerns the elision of older, longstanding cultural practices. In the decolonizing movement after the Second World War, the popular masses in Southeast Asia experienced nationalism as a progressive force to unshackle themselves from colonialism. However, it is problematic to think that the nation-building process was concluded in the 1960s.

Today, it seems to me that the contemporary artist is more interested in mining for these long forgotten visual, cultural “traditions.” The younger documentary photographers working in the Philippines, Thailand or Singapore will continue to reference World Press Photo or Aperture. The earlier generation would speak of Life magazine or Time. These are still the reference points, which are essentially from the USA and Europe.

I do not think that has changed much, but there is another history to be written. For someone who lived in Southeast Asia during the 1950s and the 1960s, they might point us to other reference points within and beyond the region. This is the case for salon photography in Southeast Asia, which was partly propagated and sustained then through the circulation of Chinese-language periodicals emanating from Hong Kong.

Salon photographers participated in regional and international contests. They received endorsements from abroad when their submissions were accepted by the Royal Photographic Society in the UK or in the photo salons organized in Hong Kong (widely heralded amongst the Chinese photographers throughout the region as the kingdom of salon). As their fame increased, the colonial/national governments sought to bring them into the fold of the nation-building project. The salon photographers might be commissioned to take photographs of the emerging nation in order to attract tourist money. Not surprisingly, what attracted them in terms of subject matter became part of the national imaginary.

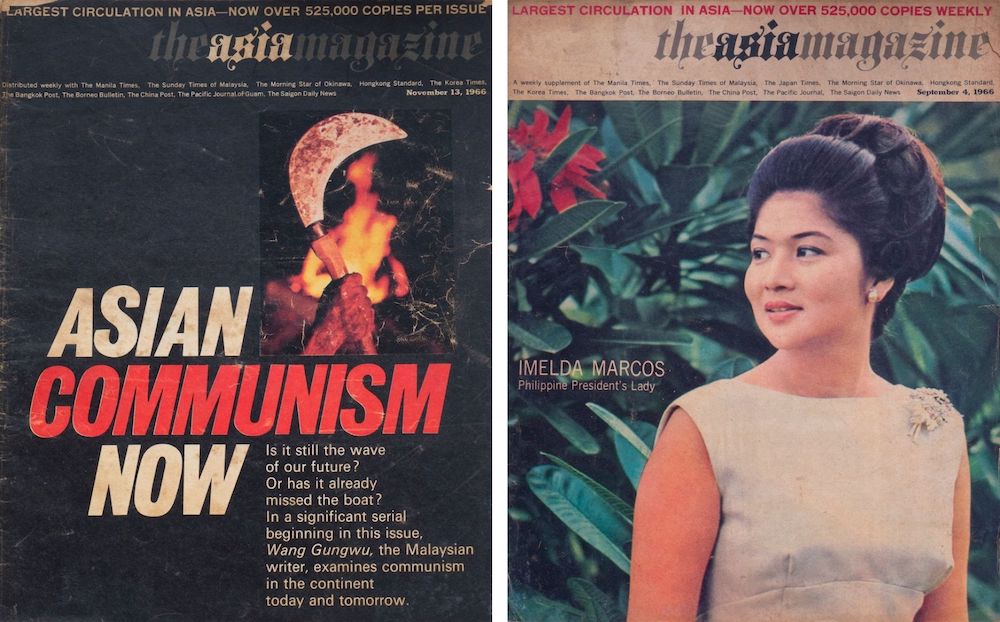

Today, there is a clearer division of labour when we talk about travel photography, photojournalism, news photography, fashion photography or product photography. This “professionalization” of the different photographic practices is more recent. In the past, the commercial photo studio did everything. In Malaya or Singapore during the 1920s or the 1930s, the Japanese or the Chinese photo studio did it all: they did studio portraiture; contributed images to newspapers, periodicals and books; and even covered colonial and state events. They did not limit themselves in terms of categories or different practices. I think that in parts of Southeast Asia, the division of labour only became more pronounced by the 1970s. For instance, a photographer working for the Chronicle Magazine (a popular periodical that took Life as its reference) in Manila during the 1960s, would have to do whatever his editors would assigned him, even though he might have a stronger interest in fashion photography. As a side track, I am also very interested in Asia Magazine. Some of the most prominent Indian photographers contributed to this magazine, which was published out of Hong Kong and Tokyo. It was in existence from 1961 till the 1990s. For many years, it was the pictorial periodical with the largest circulation in Asia. In most cases, it came to the households of Asia as a Sunday supplement to the local daily.

Returning to the story of salon photography, the postcolonial state continued to be a major patron. In that era, if you wanted to make a living in Vietnam, Malaya or Singapore, the state would be one of the major patrons. Of course, the state would be attracted to the fact that you were an award-winning salon photographer. That was the avenue for photographers in the emerging nations to gain recognition through the external and regional framework of salon photography. That was how the praxis of salon photography became entangled with the desires of the nation.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer who makes photographs, publications and exhibitions. He is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, “Chineseness,” and the Cold War in Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. Wubin received his PhD by Published Work (Research–Photography) from the University of Westminster, London.