Editor’s Note: A Part of My Life…

My thinking is not separate from objects… the elements of the object, the perceptions of the object, flow into my thinking and are fully permeated by it; my perception itself is a thinking, and my thinking a perception… There is an empiricism which so delicately involves itself with the object that it becomes true theory.

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe[1]

As we go to press (digitally at first) with this issue, the world is in “lockdown,” and a new planetary moment afoot. Some people are already home, while so many prevented from returning in the face of a new contagion, Covid 19. Families are trying desperately to come together, keep each other safe, but fighting an invisible force which has very clear and pronounced effects – migration and politicisation, to communal intensification and resource scarcity. Drawing upon a recent exhibition that I curated as part of the Serendipity Arts Festival titled, Look, Stranger!, there too, the very thematic of the unknown, uncertain, often unreliable and unstable were the very points where personalised interpretations of our current realities become “emplaced.” They suggest that when we cross certain real or imagined thresholds, we often encounter a moment of radical estrangement which, over time, we can make familiar and absorb into ourselves, and sometimes not… Both, from one’s own self and the selves of one’s “others” – our personal paradigm and place provokes us to reflect in broader terms – on the question of external affiliation and belonging, on tangible links to collective histories and identities, on the evidentiary potential of memory, and on the meaning of self-representation and its intimacies.

In a lifelong attempt to bring visibility to an indegenous group, we see a dynamic play of image-making and anthropology realised by Swiss-born Brazilian photographer, Claudia Andujar. In the ‘60s, she presented an exhibition titled Familias Brasileiras (Brazilian Families), which documented indegenous communities in Bororo and Xikrin, before joining a magazine Realidade. Influenced by W. Eugene Smith, she would eventually take some of the most powerful social documentary, politically engaged images associated with family life of the community, the Yanomami and their struggle for survival.[2] One of the most important aspects of photography in postcolonial cultures has been the making visible of various conventions around the depiction of micro-political and domestic spaces. Aesthetic enactments or performative renderings created through different media and diverse iconographies reveal the individual and social methods through which we try to create permanence for ourselves within an essentially transient world, and it is here that the family as an entity is always acknowledged and returned to.

Exhibitions like these, as well as archives which house family photographs alert us to the shifting contextual dimensions which may condition our approach and research around such images. A recent article by JNU professor Suryanandini Narain brings into focus various institutions and personal collections of family photos indicating how departures from the primary locations in which such informal images are made and circulated, can change their meaning.[3] Furthermore, by looking at specific collections such as the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (established in 1993), the School of Women’s Studies at Jadavpur University (which archived images between 1880 – 1970); the photographic engagements of Dayanita Singh and Umrao Singh Sher-Gil; and even films such as Nishtha Jain’s Family Album (2011) – she draws attention to how mnemonic devices can present alternative historical facts.

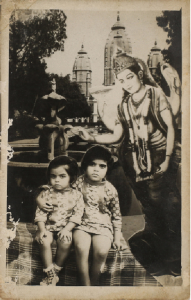

An image from the Patel family albums. Courtesy of Divia Patel.

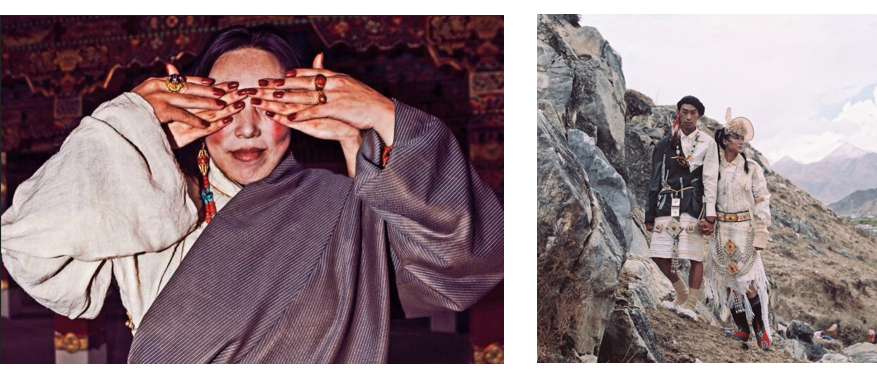

Nyema Droma, Modernizing the world roof. Lhasa, Tibet. 2014; Nyema Droma, From the Sons of Himalaya series. Lhasa, Tibet. 2015.

The works in this issue, some of which present artists’ interventions around family archives, further endeavour to distil the contentious relationship between the documentary and the staged, and scrutinise the apparently unremarkable dimensions of the everyday that, upon closer inspection, reveal disorienting and re-orienting truths. These images bring visibility and invisibility into dialogue in different ways, asking whether any familial phenomenon can in fact be entirely known, or whether its liminal, ephemeral aspects – not amenable to verification or calibration – will always elude/ deceive us?

Much of what is volunteered here, such as the works of Yashna Kaul (p.178), Sarah Ainslie (p.188) and Lucero Alomia (p.220), are essentially about piecing fragments, a trans-generational reverbration sometimes realised as “postmemory” that straddles the personal and the impersonal, the after-image, to gradually reconstitute our sense of material place, and our sense of ourselves as solid inhabitants of it. Reconstituted photos like these as well as sensitive documents, revealed and coalesced by Priyadarshini Ravichandran (p.140) and Rajyashri Goody (p.210) offer the experience of re-aggregation, the return to the self through a duration of dispersal. They remind us that internal “snapshots” – those instantly found, felt and framed as well as momentary flashes of the past that live on as an imprint on consciousness – and the mysterious mechanisms of their recall, are ever-present as a field for the practice of archiving family histories or trajectories, and invite our participation accordingly. And together, they further propose – what makes us capture one another for posterity? When people come together or separate, how does the photo seal their pasts and condition their future? And in the end, who decides what each of us may consider a family to be, especially since so many lifelong affiliations lie outside the bonds or ties that are created through birth and circumstance?

The breadth of archival traces and contemporary trajectories in this publication furthermore engage or activate certain theoretical stances, drawing upon the works of practitioners who see great value in recasting their relationship to the family image that is amassed through found material in their homes, or those recast from altarpieces which may have become ossified as stark reminders of where we come from, but don’t necessarily define us entirely either. In constant tension between “being” and “becoming,” between the story of our past and those we chose to ally with in our time, the family photo presents a personal paradigm that means something to everyone given the histories we carry with us, and this is where the introductory pieces of the FAMCAM group position the place of the family photo.

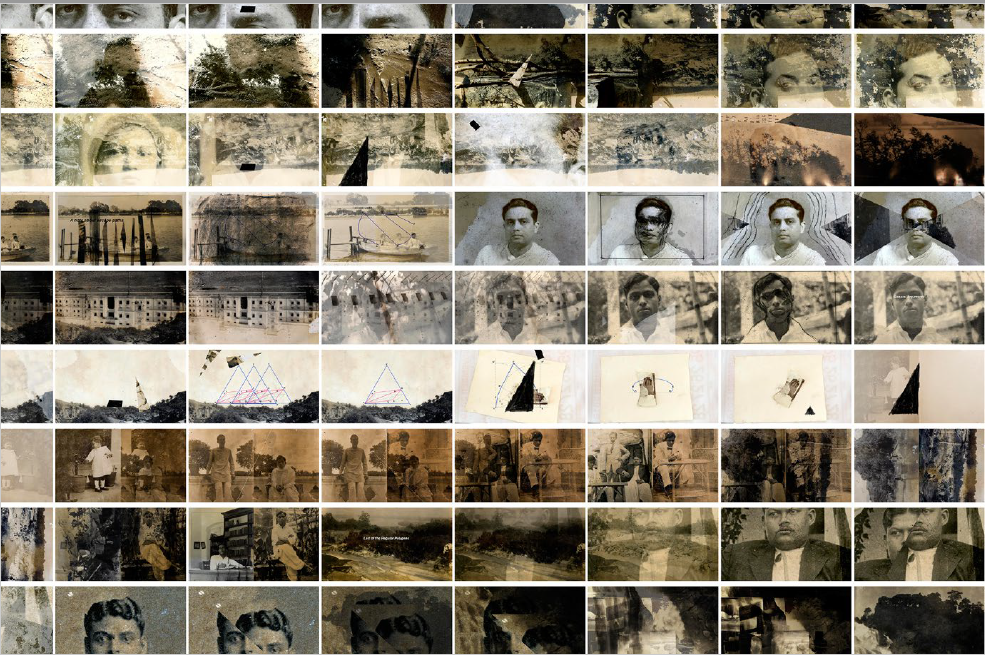

Sukanya Ghosh, Isosceles Forest. Single channel video, 2018. 3’ loop, archival photographs, mixed media and animation.

In more recent times, we have seen how memorabilia, the keepsakes that we treasure can also become politicised –they are indelible markers of how the state may consider someone an “insider” or an “outsider” depending on the documents we keep (take for example the recent, undemocratic CAA Amendment Bill). Hence the thrust of this issue is also about what comes to define the self through others, and vice versa. Some of the most important spaces that contain personal documents as historical traces in South Asia are the memorial or Partition Museums in both India and Bangladesh, drawing attention to explorations of history through lived experiences, even indicated in this issue by practitioners Philippe Calia (p.38), and Anita Khemka and Imran Kokiloo (p.46); or outside the publication seen in the works of artist Siva Sai Jeevanantham who has addressed the disappearances of Kashmiri persons, and hence depicted the narrative of loss and retrieval. They explore, to an extent, how individuals when faced with circumstances outside their control, try to seize control of their own memories and even lives, by drawing upon the importance of their own relationship to places and people that can never be eradicated. These are in essence, paradigms that can never change, but are always in motion, always needing to be recalled and adapted to circumstance.

One of the key aspects through which the writers address the complicated aspects of belonging and displacement, is by addressing dominant strains within the images, and moments wherein the congregation of people which is documented is defined by an event, a moment that conditions “how,” “when,” and “why” the images are then taken. But on the other hand, so many of our associations to images come from having discovered them or seen them for the first time, unleashing trajectories through lapses and secrets that we may not have known, pasts we may only now be discovering. The space that these images open up are taken by artists as raw data through which the construction of their own narratives commence… And we see this even from outside the issue, in works such as those of Sukanya Ghosh, wherein she generates optical collages and montaged prints, and hence questions provenance, often erasing or rebuilding that which is contextual, traceable, or linear through an interplay of historical and narrative time.

Another early referent to this can be considered the work of Mohini Chandra, who in the ‘90s created a series in which she replaced individuals from the image with symbolic landscapes that were then inserted into their silhouette. Or indeed the works of Ayisha Abraham such as The Firefly Filled Night Goes by Like That (2016), a recent self-published book which volunteers images taken in the vacant house of her maternal grandmother situated in the cantonment of Bangalore – and she transformed the house for one month prior to its demolition into an arts space. For Ayisha – history, memory, and the archive, come together through a process that began in 1991 with four photos and a letter from her grandmother. Examples like these focus on the affective power of photography that stems from its ability to trigger responses, shifts, and modulations that are unexpected and ever changing. On the other hand, looking at another article outside the issue by Divia Patel (from the Victoria & Albert Museum, London), which charts the migration of her own family from East Africa to Britain, pinpointing the essential question of where we come from or belong. A similar arc is drawn by artist Arpita Shah, through her series a Portrait of Home (p.025), or more recently Nalini, where the artist looks to capture memories of her maternal ancestors. As noted by art historian Emilia Terracciano, in the latter series, “Botanical icons become metonyms for other continental ecologies and testify to the experience of growing up…”

Extendedly, as historian Benedict Anderson suggests in Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983), nations, like families, are socially constructed phenomena, ideologically verified and validated through, among other processes, numerous inter-personal strategies. All nations have their “national” archives, as do families. Another work outside the issue which is pertinent here, is inspired by a photo of a bare-chested Bengali peddler from the People of India series. Artists Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall embellished the anonymous subject by adding a 1940s-style suit, simulating a transformation of the colonised “native” into a completely unrelated entity: a black jazz musician from Chicago. This arbitrary transnational re-contextualisation recalls another narrative of traumatic subjugation and racist violence that has left its own suppurating, indelible traces upon a continent.

The stark allure of this audacious image invokes philosophical arguments about “reality” and “illusion,” as well as issues around the revisionist augmentation of “national” cultural history. It also interrogates the false universalism of the categories “nation,” “nationalism,” and “national” identity, which play out often when we think of family.

Disciplinary power… is exercised through its invisibility; at the same time it imposes on those whom it subjects a principle of compulsory visibility. In discipline, it is the subjects who have to be seen. Their visibility assures the hold of the power that is exercised over them. It is this fact of being constantly seen, of being able always to be seen, that maintains the disciplined individual in his subjection. —

Michel Foucault[4]

As I have also stated in Look, Stranger!, I invoke once again here, Foucault, who warns us to beware of describing the effects of power in negative terms – as repression, concealment, abolition, censorship, etc. – asserting that in fact power does not negate reality but actively generates it through a range of applications and instruments, or “technologies.” He reminds us that the “interdiction, the refusal, the prohibition, far from being essential forms of power, are only its limits, power in its frustrated or extreme forms. The relations of power are, above all, productive.” In Foucault’s thematic, the exercise of power constantly produces knowledge, and knowledge constantly induces effects of power; knowledge and power are co-conspirators, inseparable, never antithetical or amenable to counter-positioning.

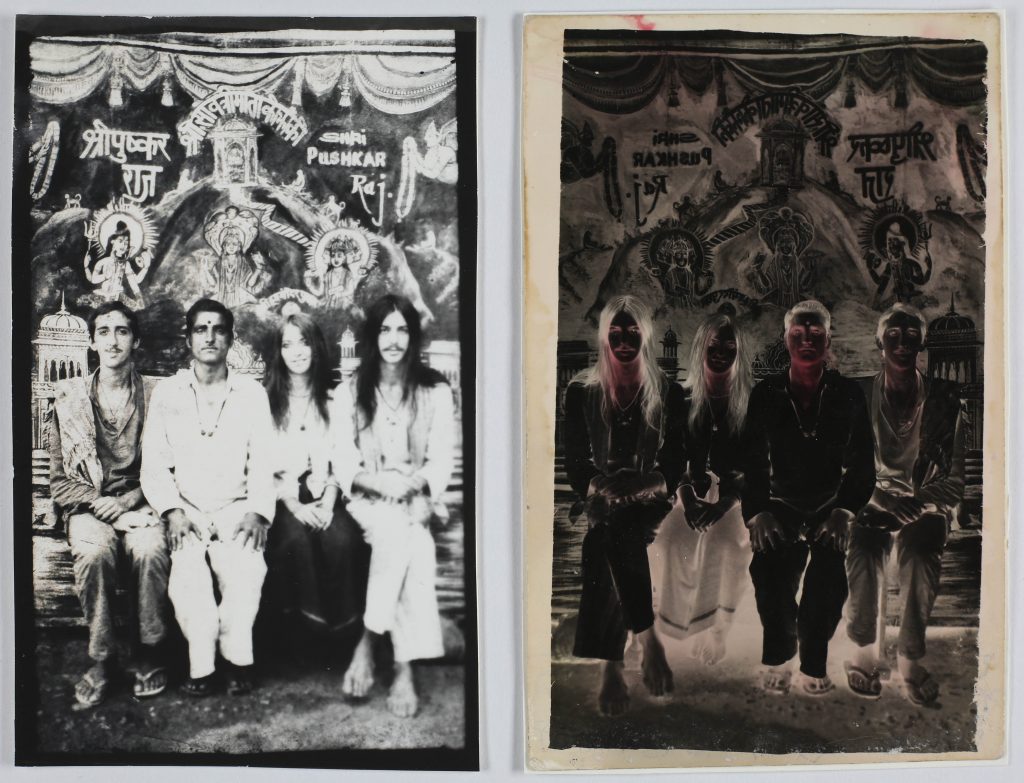

Bharat Bhushan Mahajan and Kinshan Chand Hemlani. Images c. 1970s-80s. Silver gelatin prints and copy negatives. Courtesy the Alkazi Collection of Photography.

Thus, power is “not an institution, a structure or a certain force with which certain people are endowed: it is the name given to a complex strategic situation in a given society.” And because power is relational, resistance to power becomes possible, since that relation, existing in different complex forms, can be modified within certain conditions, and according to certain strategies.

The politically informed works of Rohith Krishnan (p.78), and from a personal perspective, Uma Bista (p.100), in this publication scrutinise the methods by which we are constituted and categorised, in both state and personal archives, and the varied aesthetic registers created through these images. In recent years there has been a concerted global shift in focus to affirming the evidentiary nature of personal images as valid forms of testimony and “truth.” The works in the first case are from family archives and in the second, by a practitioner going into personal spaces; these present the need, across our arts and media discourses, for the documentation of alternative histories, and the magnification of subaltern, regional, and vernacular voices, rituals, myths, and practices as a counter-narrative to aggressive majoritarianism.

Can the notion of “personal paradigms” then be extended to the theme of surveillance, to be theoretically explored by association, and invite viewers into mirroring a kind of experience where certain communities are registered and biometrically indexed in order to be verified as “legitimate.” This now-normative practice exemplifies the need for resistance to the state panopticon, as well as to current ethos of toxic identity politics, xenophobic suspicion, objectification, penalisation, and demonisation of the “other,” those on the periphery, those deemed deviant – the migrant, the stranger, the outsider, marginalised minorities, and all those who for one reason or another cannot or will not assimilate into the hegemonies of “national” culture.

Can they then make us focus on the complexity of bringing to light the notions of love, bonding, and solidarity that we see in the works of Harikrishna Katragadda and his partner Shweta Upadhyay (p.150), or infact Srinivas Kuruganti (p.232) – all manifestations of free association, and against the grain of any stereotyping.

We must then also look at memory and trauma as vectors that also emanate from violation and manipulation that may occur within the family net, boldly articulated in the recently manifested installation of Indu Antony titled Vincent Uncle (p.26-27). Can they bring us to focus on new initiatives of Goa Familia (p.114)and a recent focus of GoaPhoto (p.106), or outside this issue, the works of Nyema Droma looking at Tibetan exiles as themselves and their imagined others – on the family as needing restitution from constant abandonment, or disappearance, and do they make us consider, carefully that though we were not in control of where, when and to whom we were born, we can assert the need to share our experiences of displacement, exile, and even settlement in order to make place in a new world.

REFERENCES

- David Mellor, Germany: The New Photography, 1927-33: Documents and Essays (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978).

- Exhibition Claudia Andujar, The Yanomami Struggle, on view at the Cartier Foundation till May 10, 2020.

- Suryanandini Narain, “In the Family: Photographic Archives from India,” in Photo-Objects: On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives, eds. Julia Bärnighausen, Costanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, and Petra Wodtke (Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge, Studies 12, 2019).

- Michael Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin UK, 1991).

Karan Kapoor, from the series Anglo Indians. 1979-1980. Tri-X film. Exhibition view: Origins, British Council. New Delhi. 2016. Curated by Rahaab Allana; A still from the film Family Album. 2011. Directed by Nishtha Jain.

Arpita Shah, The Azad Family. From the series Portrait of Home. 2014. Medium Format, 120 Film; Nyema Droma, Untitled. From the Sons of the Himalaya series. Damxong, Tibet. 2015.

Indu Antony, installation view of Vincent Uncle, at Serendipity Arts Festival 2018. Panjim, Goa. Installation photography by Philippe Calia.

The pieces in this project are autobiographical and investigative in nature. The artist is investigating Vincent Uncle and in so doing is investigating the male figure within the Indian family. Each image is like a piece of evidence, almost scientific in nature. The theory of psycho-cybernetics (self-help through visualisation) mentions that it takes twenty days to make or break a habit. The artist applied the same theory to the exercise of creating this body of work, she photographed twenty-one legs to explore my memory of Vincent Uncle’s hairy legs, the images are all shot at a certain height, as if seen by the eyes of a child. The Mundu (a loose piece of cloth worn by men in South India) is worn and has been used to indicate her personal history in South India. Another significant element was the smell of Vincent Uncle and how he used Attar (a natural perfume oil derived from botanical sources which when mixed with body sweat has a particular smell). The smell was not pleasant. The artist collected and bottled sweat from multiple men to stimulate a nasal memory. While the memory of my uncle slowly resurfaced, in pieces, dreams were dominant for her during this phase. She chose to create films of these dreams and later they became part of the installation titled Dream Doors.

— Text by Anna Fox