Indian Memory Project: Materiality and Tactility

“He left behind several boxes of photographs and slides that he had taken as an immigrant in UK. My need of engaging with his memory was to look and re-look at the photographs and relive the stories about the images he would narrate often. Naturally then, for me a photograph, any photograph, then had to have a story.”

– Anusha Yadav, Founder, Indian Memory Project.[1]

Indian Memory Project (hereafter IMP) is a visual, online archive with biographical sketches and details that traces unearthed vintage, modern, and contemporary histories of photography from the Indian Subcontinent. With over 200 submissions, IMP initially started as a Facebook group, where Anusha Yadav, its founder, invited people to post their wedding photographs, given its currency in the present. Driven by an enthusiastic response and the sheer desire to volunteer their stories, people began to share family histories, portraits, and other situational and event-oriented images from their own family albums, and therein began the birth of a platform beyond its initial mandate.

This online resource now spans across Independence-era images that deal with the trauma of Partition, bringing to light aspects related to migration, exile, and displacement that are also narrated through anecdote and recollection. This very fact, has expanded its potential in a globalised world, wherein questions of origins and “home” have become a complicated terrain with unprecedented implications.

Anusha’s initiative of making a sub-continental album out of collective memories – snippets from personal albums, diaries, loose images – began in 2010. This “album” is one of the largest repositories one may say of “personal paradigms,” wherein encounters and experiences of love, loss, intimacy, and secrecy, are channelled through individual accounts or shared as excerpts from the “family album.”

In the archive of IMP, these first person stories are an entry point also into how a certain politics – the perception and retelling of a historical context through biography – is communicated through transitions and challenges a family or community undergoes. And so many of these photos relate to the tradition of the “snapshot” – taken during matrimony, death and birth ceremonies, everyday encounters, feasts, travels among several other incidents. The question I was interested in while looking that these images and the way in which they are shared through an online forum, was their modes of circulation – I wanted to know how a story gets affected or changes when these personal snapshots are put in the public domain and studied as part of a people’s history?

In her book, Snapshot Photography: The Lives of Images (2013), Catherine Zuromskis remarks that such imagery is an intensely private and personal form of photographic representation, however as a cultural convention, it is also one of the most public iterations. This tension between the snapshot’s private and public lives points to a more fundamental paradox. On the one hand, the genre is often identified as “photography at its most innocent,” while the aesthetic shortcomings of the photographs discussed above are typical of the genre. The snapshot photo is often mundane and formulaic, characterised by stiff frontal poses and choreographed moments. It is also all too commonly marred by technical blemishes and faults – such as the lens flare, a misplaced finger in front of the lens, an improper exposure, or crude lighting. But however awkward the pose and imperfect the expression, the photographic trace of a friend or loved one carries a significant existential weight, an undeniable assurance that, to quote Roland Barthes, is an important indicator of temporality and the event itself, a moment “that has been.”

The importance of these, and other snapshots only increases with time because of how these personal images offer a glimpse of the past, providing us a sense of cultures, traditions and the heritage of the subcontinent. More importantly, each of these images have a story narrated by the sitters, or their kith and kin. Text plays a crucial role, as often these are contextual or regional and contain the inflexions of traditions and experiences that may be well beyond the grasp of the reader. But one may also ask, without this preliminary step of exposure and volunteering, how else are these micro-narratives to come to light and whether the act of showing itself is the first step towards the discovery of elided histories.

These personal accounts, presented as an archive of “memories” help shape the outlook of the history by ushering an intimate understanding of the impact public events have had on lives of the people. The history taught to us through official means on the other hand, lays emphasis on chronology and ways in which policies have been administered and executed. The importance of this is undeniable yet one may then erase or unknowingly discard a learning from people who were a part of making history, of experiencing the aftershocks. Hence the pedagogical implications of personal histories, that have so impacted our sense of “what matters” and “how,” is one of the key trajectories imparted by the IMP.

And in this process, archiving itself becomes an important means and filter. The process itself may condition how we consider identity as fluid, freewheeling and unfixable. Letters, photos, and other documents, ones which today may well account for our “citizenship” to a place, or discount us as residents of another – dug out from rusted trunks strewn with naphthalene balls to prevent silverfish from feasting on the artefacts of our ancestors – how far do these create an alternative assessment of “belonging,” of considering our allegiances and affinities in times when our documents can become fossilised, indefinite, rigid and permanent imprints of our now shifting lives.

One can argue that the “digitisation of memories” may not have the same impact as an encounter with the “real” object, and this distancing itself curtails how one may read notions of identity in the present. But while the ability to encounter the actual works is indeed important, this growing interface perhaps reflects more accurately the place of communicability and exchange in the present. How else are we to share our experiences across boundaries and continents with ease if not through the new fibre optics that allow for sharing platforms and strategies to proliferate without the fetters of an “official” structure of dissemination. The IMP therefore induces us to think not only about the narratives that ebb to the surface, but the question of materiality and tactility.

“They started conversing about things I hadn’t anticipated. When these conversations happened, the vocabulary of it started forming categories in my head. When there is a category, there is a library, and that is how it fell into place, slowly and steadily.”[2]

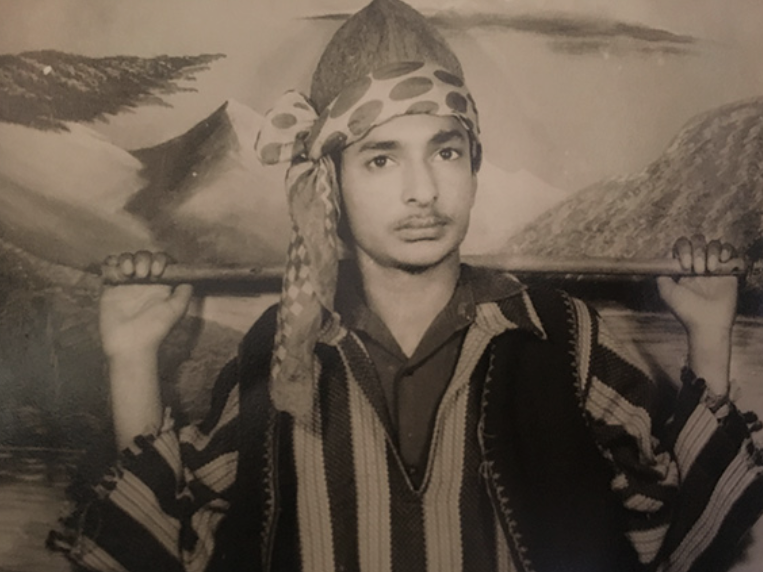

The Pocket Money Photograph

Born in 1968, Subhash grew up in Bhatinda, Punjab. After taking his Board exams, he took a trip to Vaishno Devi Temple with his parents. Fascinated by the idea of solo photograph, Subhash managed to get away from his parents’ eyes and sneak into a photo studio where he dressed in a Kashmiri attire and posed in front of an old camera. Subhash spent half of his pocket money (5 paisa) to secretly get this photo taken. (Image and narrative contributed by Sayali Goyal, New Delhi, IMP)

Subhash Goyal. Vaishno Devi Temple premises. Jammu & Kashmir. 1979.

Matrimonial Picture of a School Girl

This photograph of Rohini Palan was taken in a photo studio not very far from her school. Rohini’s father showed this picture to the prospective grooms and fixed her alliance right after she had returned from school. (Image and narrative contributed by Manorath Palan, Mumbai, IMP)

Rohini Thejappa Palan (nee Talwar). Bombay. Maharashtra. c.1939.

They Committed to Photos, and Married Four Years Later

This portrait of Nazni Naqvi with her husband, Hadi was taken on their wedding day. Nazni fell in love with Hadi the moment she saw his matrimonial photograph. She insisted on marrying him and four years later, this picture was taken on the terrace of her parent’s home, a hundred room palace in Patna from where she moved to a two bedroom government allotted flat after marriage. Nazni’s story is one of the most heart-warming love stories in the archive. (Image and narrative contributed by Nazni Naqvi, Mumbai, IMP)

Imam Hadi Naqvi and Nazni Naqvi, a few days after our marriage. Patna, Bihar. 1958.

A Teenage Couple’s Fight for Freedom

Chameli Devi was a Gandhian fighting for India’s freedom from the British Raj. She was 14 when she got married to Phool Chand. Holding hands in public, even for a married couple was seen as unusual. But defying the conservative majority Chameli Devi posed for a photograph holding hands with her husband. Her defiance went much beyond that. She marched with the women and joined protests, faced arrest for months. And when she was released, she wore her Ghoongat a few inches higher and wore only hand spun clothes. Her stories of resistance are known to one and all and she has an award named after her.(Image and narrative contributed by Sreenivasan Jain, Delhi, IMP)

Chameli Devi Jain and her husband, Phool Chand Jain, shortly after their marriage. Delhi. c. 1923.

My Grandfather’s Secrets

These photographs belonged to Jason’s grandfather, Bert Scott Bert avoided talking explicitly about these photographs but the intimacy in the pictures made Jason so curious that he sat down to crack the curious case of this girl in his grandfather’s album. His only clue was his grandmother’s passing remark on seeing the album, “those books are just full of photographs of his ex-girlfriends!” Jason began to chase his grandfather’s past and he was lucky to find out that this girl was his grandfather’s love, and they had to part ways when Bert and his family left India during Indo-Pak Partition. When he found out Margurite was alive and living in an old age home, he got in touch with her daughter and sent her photographs of Bert and Margurite Margurite’s memory was dimmed but soon after seeing the photographs she asked, “Is Bertie here?” (Image and narrative contributed by Jason Scott Tilley, Coventry, UK)

Margurite Mumford, and Albert Scott. Ooty & Bombay. 1930s.

The Only Valuable He Saved While Fleeing to India in 1947

On October 2, 1947, during the partition Anand and his family were told their Mohalla was going to be attacked by rioters from another community. The family had minutes to pack all their necessary belongings and leave from Rawalpindi. On reaching Delhi, Anand’s father took stock of what valuables his family members had carried. Upon seeing what Anand had carried, he lost his temper- “Why did you not carry valuables!? What useless things have you carried with you? How can we survive without our valuables? You should have carried some valuables!” He lost his mother, Sumitra Bali, when he was around nine years old. On being yelled at, he told his father – “Money we can earn when we find work, but if these photos of her were lost, no amount of money could ever bring them back for me. Pictures of her are all I have to live with, my entire life!” (Image and Narrative contributed by Rakesh Anand Bakshi, Mumbai)

Anand Prakash Bakshi as a child with his parents. Rawalpindi (now Pakistan). c.1930.

Zainab Mufti is a visual artist and writer based in Kashmir. She is pursuing her BA in Journalism and finds refuge in photography and writing.

Notes

1. & 2. These quotes have been extracted from a telephone interview with Anusha Yadav that was conducted on 28th January 2020 by the author.