Kashmir: A Lost Childhood

Left: Family Holiday I. Aru and Pahalgham. 1985. QSS print; Right: Family Holiday II. Pahalgham. 1985. QSS print.

- Can you talk about the phases of this project and the challenges of doing so now through the perspective of your own family?

Anita Khemka: This work started as a reaction to an extreme experience. We were on one of our family trips to Srinagar in 2016 when we got housebound as there was a two-weeklong shutdown of the valley. I experienced such a complete lockdown for the first time and it made me acutely aware of the freedom we take for granted. Our initial work of making portraits, in print and x-ray, of the victims of pellet guns began as a compelling need to document the wounds, both physical and psychological. They were made for the sole purpose of creating a “document of proof” and the people participated with a stoic response as their way of protest—they stood in defiance, announcing their identity, not wanting to be portrayed as victims.

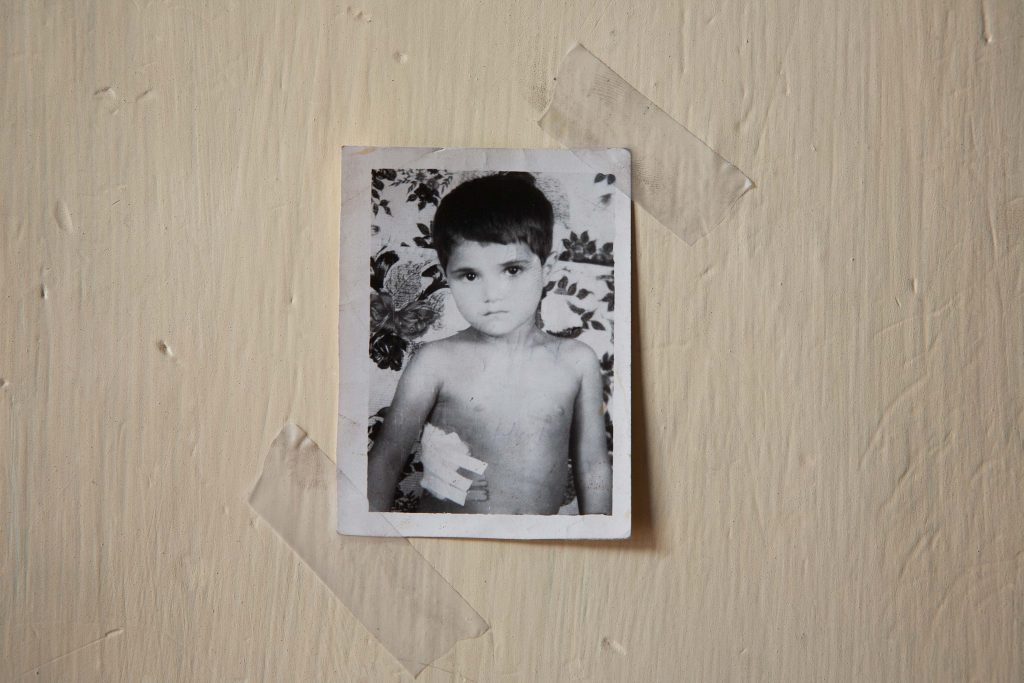

Imran Kokiloo: We realised that the scope and scale of our work was far more than the images of wounds and the response by the people recipient of them. This led to the second phase which involved documenting various tropes of memory — clothes, notebooks, identity cards, photos, documents, and other belongings that families treasure, as memories that had been arrested. This led me to explore my own growing up years in Kashmir. I started making pinhole images of the landscape as an attempt to anchor the memory of my home; a landscape, which bore a mood of uncertainty and urgency then. The melancholic feeling, which hung heavy as fog, has stayed and continues to filter all my memories of that time.

Anita Khemka: Our daughters sleep in gay abandon at our home in Delhi. These images are in stark contrast to the memory Imran has of his own growing up years, which were much more guarded and unsettled. This dichotomy is a grim reminder of the normality and innocence lost and the association it has with geography. Then again the photos in the family album of Imran and his siblings, which were made before the current conflict started, are not very dissimilar to the ones we make of our own children now during our holiday visits. Perhaps we feel a compelling need to make similar photographs of our children with a landscape that is seemingly, equally calm, beautiful, and serene. Maybe it is an attempt to obliviate, suppress and even recalibrate memories of trauma, stress, and anxiety that Imran has witnessed as an adolescent and has since inherited.

Anita Khemka & Imran Kokiloo: With this latest phase of our work, the challenge for us has been at a very personal level. As the understanding of our own journey in this work evolves, the images of our children make way alongside the photographs of children and young adults who were last seen twenty-five, even thirty years ago. Their memories suddenly frozen with that last photo or belonging held by their loved ones. Or the image of a woman holding the photo of her disappeared husband in her lap as she talks to us; she has aged and now the husband looks like her son. These are very disturbing thoughts, knowing well that we and our children share our identity with all of them. The them are us.

Home I. Srinagar. Goa and Delhi. 2017-19. Digital.

Home I. Srinagar. Goa and Delhi. 2017-19. Digital.

- What for you, through this project, is the place of Kashmiri identity today, even for yourselves, given so many of these histories remain hidden on the one hand and bound to a national politics on the other?

Imran Kokiloo: Kashmiri identity has been limited to a few words by the political discourse today. It is commonly referred to as Kashmiriyat by all without actually defining what Kashmiriyat is. Like all histories, Kashmir’s history is very complex and the identity which has evolved with it is equally complicated. It is layered with memories of repeated tyranny and subjugation at the hands of conquerors. The fact that Kashmir was sold by outsiders to outsiders with no agency for the “natives” has been engrained in the collective.[1] Even though Kashmir has in the past been an independent entity and state for much longer than Modern India, yet there are no national icons for Kashmiris collectively, from before the beginning of the last century. The Kashmiri identity for some time now has unfortunately been chafed by the religious identities of different communities, with the attachment to the Rishi-Sufi culture and the scenic landscapes of the land proving to be the only common catharsis.

Found. Srinagar. 2019. Digital.

Anita Khemka: Our work deals with the present. It is an attempt at recording what we feel today as a family that identifies as being Kashmiri at various different levels. It is about Imran, a so called “native;” it is about me, an outsider, and by virtue of being his partner, and having kids together, how as a family we are tied down to the whole history and narrative of Kashmir. As this work evolves, we are slowly removing the faces of others in our images and bringing in our own and making indexical references to completely new stories.

Imran Kokiloo: Through personal photos, be it the photographs of my sisters and myself or of my parents of early ’80s or the pinholes that I made in 2019, there is an attempt to attach the geography with the identity; the landscape with the memory. The fabled “firdaus,” a term coined by conquerors, is what we have inextricably tried to link ourselves to.[2] The family images are still made as they always were against the scenic beautiful landscapes of the valley. However, the frame is more deliberate, particularly in current times, when we are carefully editing out the blood and violence from the borders of our images. This is an illusion we are carefully crafting for our own and our children’s memory. This might well be a lie, but isn’t this lie important for us to hold on to for our identity?

- What is the story you would like to communicate in the end, not only to the reader, but your own families and children when they see this project as a whole? Has it already elicited some response?

Imran Kokiloo: With this work, we want to pose some questions about the identities we all assign to ourselves; and how that fits in the greater political theatre playing over various time periods. Aren’t all the excesses done by one group of people to another about ascertaining identities or even imposing them? Geographies remain for eons, yet we all claim possession of it knowing well we can’t hold it for long. Either we perish or nation-states do. Then what is it that we are claiming, and from whom? How is the identity of an individual linked to that of the collective and how do we guard its purity even in the bleakest of times? Agha Shahid Ali in his poem Farewell, writes, “My memory is again in the way of your history… your history gets in the way of my memory…” The narratives and counter-narratives that we are working with are all about this constructed identity.

Petitions. Delhi. 2019. Digital.

Anita Khemka: We hope that this work will communicate the struggles people go through in order to give meaning to their own identity. It also hopes to probe as to what gives birth to the self. How does one belong and who defines that criteria? How does a particular geography become a part of one’s being? For our own family and children, these become important questions and through this work, we attempt to find some answers. We look at photos of Imran and his siblings made thirty years ago by his father, and we look at the photos we make of our children. Is it that we are trying to preserve and even relive memories of Imran’s childhood, which was calm and genuinely serene? Are we at some subconscious level trying to subvert factual events of the land that our children are invariably connected to?

Anita Khemka & Imran Kokiloo: Communities, and sometimes even individuals have had to carry the burden of representation for an entire population. We would like our children to see, how without knowing and understanding, we all carry this burden; and how frivolous the questions of identity can become.

Anita Khemka’s practice of twenty-five years has focused on gender, sexuality, and identity. She is also an educator and currently works for The Murthy NAYAK Foundation as a researcher and is represented by PHOTOINK.

Imran Kokiloo is interested in alternate photographic practices and printing techniques. He is committed to controlling all aspects of image-making — right from making the camera to the final prints.

Interview with Rahaab Allana.

Notes:

-

-

-

-

- Refer to the Treaty of Amritsar between the British Government and Maharajah Gulab Singh, March 16, 1846. http://jklaw.nic.in/treaty_of_amritsar.pdf

- Appropriated and inscribed by Zafar Khan, the Governor of Kashmir, under the Mughal Emperor Jehangir on the Black Pavilion of the top terrace of Shalimar Bagh in Srinagar from the sayings of famous Persian poet Amir Khusrau “Agar Firdaus bar ry-e zamin ast, hamin ast-o hamin ast-o hamin ast.”

-

-

-

Belongings I. Baramulla. 2019. Digital.

Displaced. Kupwara. 2019. Digital.

Zero Bridge. Srinagar. 2019. 4×5 film.

But my love exists even today. Budgham and Kupwara. 2019. Digital.

Portraits of pellet victims. 2017. Digital.

X ray portraits of pellet victims. Srinagar. 2017. Stitched digital x-rays.