Movement and the Making of Home: Family Photographs Through a Transnational Lens

Family photographs often convey a sense of place, a sense of home. They seem to fix people to a location and to each other. Indeed this stasis, one could argue, seems in direct contrast to the increased mobility of people around the world over in the twentieth century, as colonial and postcolonial realities made, dissolved, and remade borders. But what if we understood the sense of home or groundedness conveyed by family photos as a continuance of, rather than contradiction to mobility? What if the seeming stasis in family photos is a direct result of movement? Tucked into a breast pocket or wallet, cut to fit into a locket, carried in a suitcase, or stored on one’s mobile phone, family photos travel with us, asserting our connection to a place and a group of people. This sense of movement seems to be a defining feature in family photos, not only in terms of what they depict but the function they serve. Mobility seems to be at the centre of a cultural practice of family photos. Ariella Azoulay suggests that photography is an event.[1] We contend that the event of family photography is movement.

What does it mean to look at family photos—their history, their practice, their imagery—through a transnational lens? What does it mean to put an economy of movement at the centre of our understanding of family photos? The following are three meditations on these questions. One focuses on a snapshot that travelled across borders but also contains other layers of movement embedded within. The second considers the material and emotional cultures of movement of which family photos are a part. The third explores the potential of the family photo archive through the making of contemporary art as a way to express alternate narratives and histories which are missing from official archives.

Jordache A. Ellapen, Family Portrait I. Chennai/Tongaat. 2017. Courtesy the artist.

I. Deepali Dewan

Family photos depict arrivals and departures as people move from place to place. In the early twentieth century in India, families had their portraits made by professional photographers before they travelled abroad in search of economic opportunities. By the 1960s, professional photographers hung around the then Bombay international airport to capture group portraits of extended family members with their loved ones who were migrating abroad, as they bid goodbye. Some of these photos stayed with those left behind. Others were made into multiple copies to be distributed. Sometimes, members who had gone abroad sent photos home, through the mail or carried by friends or relatives who were visiting. In these cases, photos would travel when people could not.

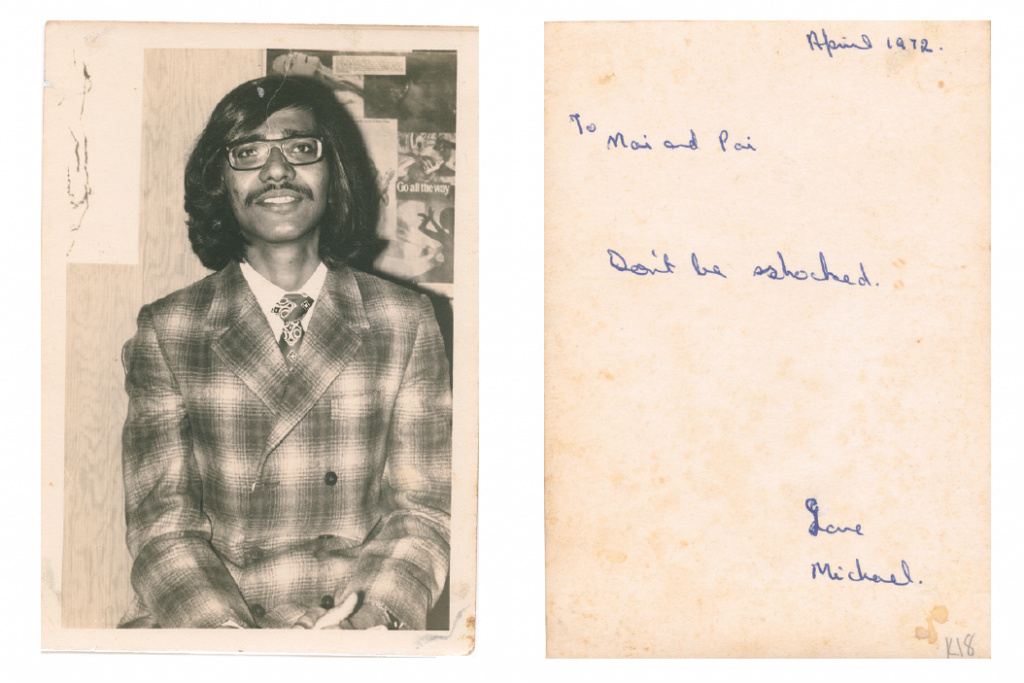

This image of Michael was taken a few years after he arrived in Canada in 1971, sponsored by his elder brother Simon who had come earlier. It is a self-portrait taken with a long shutter cable connected to his Miranda, a single-lens reflex camera manufactured in Japan that Michael bought with money from his first Canadian tax refund.[2] The first one to own a camera in his family, Michael took a series of similar images and sent them back home to his parents in Karachi.

“To Mai and Pai,” he wrote on the back of one photo, “Don’t be shocked. Love, Michael”—referring to his long hair. The photo travelled to Karachi likely through the mail as a way of keeping a connection between Michael and his family back home. The writing on the back of the photos—indexical traces of his hand paralleling the indexical trace of his body in the image—conveys both proximity and distance. I am the same and I am not the same, the words seem to say, and I know how you will react.[3] Both the words and the image negotiate familial intimacy, based on a condition of movement. But this image is associated with several other movements as well. It returned to Canada with Michael in the 2010s, along with other images he brought back after a visit to Karachi when his sister Louisa passed away. Most of the photographs chronicled Michael’s childhood in Karachi, but a few reflected Michael’s family’s migration from Portuguese Goa in the 1930s, before Michael was born. What does it mean for family photos, despite where and when they were made, to be shaped by multiple migrations? How many kinds of movement can be found embedded in family photos?

Movement has been a part of photo history from its start. The evolution of the camera followed a trajectory to become smaller, cheaper, and easier to use in order to enhance its accessibility and portability. The very names of early cameras expressed this intention for portability, and hence, movement —the Folding Pocket camera, the Vest Pocket, or the Tourister. At the same time, the development of the camera coincided with the exponential movement of people around the world due to the trajectories of colonialism, nationalism, neo-colonialism that impressed their legacies of dislocation and relocation on the traveller, explorer, migrant, immigrant, labourer, and refugee. As families were reconfigured, the cultural practice of family photos shaped and was shaped by an economy of movement.

Michael D’Souza, Self-portrait. St. Catherines, Ontario. 1973. Gift of Michael and Colleen D’Souza. Courtesy The Family Camera Network, Royal Ontario Museum collection. Gelatin silver print. 11.6 x 7.7 cm. 2019.82.28

II. Thy Phu

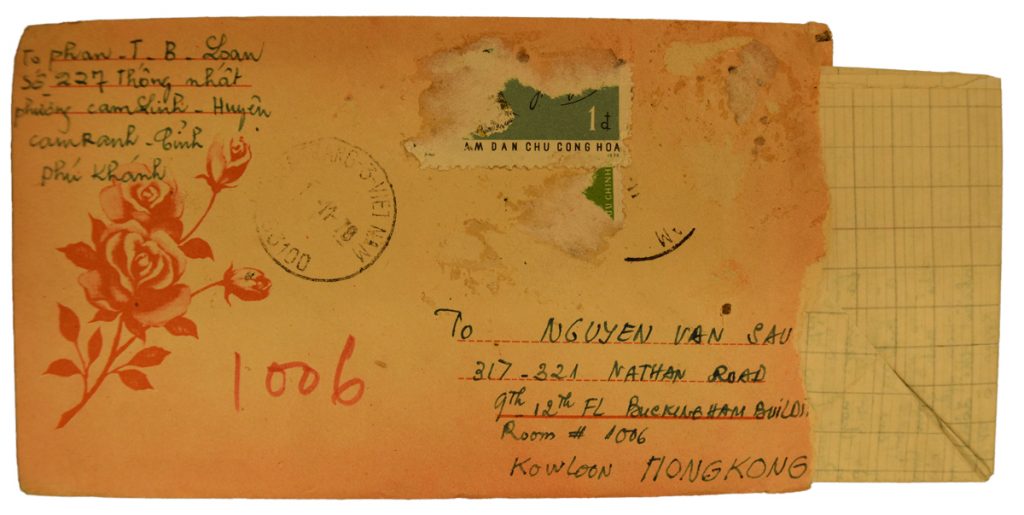

“Where are my mother and father?” Thai Khanh Duong asks in a letter to his sister Luong, written in November, 1978—a cry carried across the Pacific from Moline, Illinois, in the U.S. to the Mayfair, Room 1006, a refugee hotel where she and her family had been staying ever since their boat reached the shores of Hong Kong, two weeks after setting off on its perilous journey from Vietnam. This was just one of dozens of missives scrawled on translucent paper, folded crisply and sealed in sometimes ornately decorated envelopes that criss-crossed oceans and seas, material tracings of an extended family’s multiple migrations, its reunions, and, it turns out, irrevocable separations. Letters are branches that unfurl and stretch to gather loved ones near. They articulate the emotional ties that bind a family together.

They are also conduits of family photos. Writing on the origins of snapshot photos in the nineteenth century, Richard H. Saunders links their increasing popularity to the development of the U.S. Post Office services, which enabled inexpensive and relatively quick transmission of images throughout the nation.[4] More than a century later, the postal service not only facilitates a national exchange of photos; it makes possible a global circuit of exchange. In 1978, a flurry of letters—many of them about photographs or with images enclosed—sent from and received by the Mayfair Hotel, a way station in an ongoing migration, suggests the extension and expansion of this earlier practice. Three months earlier, in August that year, Luong wrote to her parents as they prepared for their voyage from Vietnam, asking her father to arrange passage for her treasured collection of family photos, which she had been unable to bring on her own journey. Her parents dispatched the albums on separate boats, while they embarked on yet another vessel. Superstitious, the family hedged their bets against fortune’s whimsies. Luong’s albums made it to Hong Kong, but as her sister’s desperate message shows, her parents disappeared at sea.

Letter to Loung Thai-Lu from a sibling, one of many exchanged while she and her family were housed at a refugee hotel in Hong Kong. 1978. Gift of Lu-Thai Family. Courtesy The Family Camera Network, Royal Ontario Museum collection.

Perhaps in reply to an unasked yet implicit question prompted by this cruel twist of fate—what does it mean, against all odds, to keep and preserve family photographs, only to lose the dearest members of your family? Luong continued to write letters to her family as they dispersed across the U.S., Canada, Japan, Vietnam, and beyond. In these letters, written in Chinese, English, and Vietnamese, she inserted family photos, copies of original prints contained in her albums. Her adult children, recollecting this unusual practice, describe these reproduced and recirculated photos as “mythical” images, which document a moment before loss and dispersal, reconstituting the family as it had been and should still be.[5] Sending these images across the diaspora, Luong sought through her missives to gather her scattered family together. Seen this way, the flurry of letters tells a poignant story of migration, family, and photography.

III. Jordache A. Ellapen

Ellapen family photograph. Courtesy Jordache A. Ellapen collection.

How is the family album a testament to the ways in which a community invests in creating home, family, and identity against forms of colonial and apartheid governance designed to render them forever foreign and alien-other? How can the family archive be used not just to mine for lost and forgotten lives, but as a site to re-imagine race, kin, and community? In re-figuring the family archive through aesthetic practices, I am influenced by the affective and haptic qualities of the family photo-album, which become a portal to imagine intimacies across time and space, and between racial categories like “Indian,” “black,” and “African.”[6]

“Family Portrait I. Chennai/Tongaat” (see first image on page) is a digital assemblage made up of various photos—a family portrait, ethnographic photos, and other digital photos—that are digitally layered and juxtaposed to create a visual narrative of movement and stasis, dwelling, and home-making. In this assemblage, a family portrait consisting of three generations of women occupies the center. This portrait is superimposed over a black/brown body suspended in the center of the image and whose face is covered with an African mask. Together, the family portrait and the body of the masked figure connect two photos that represent two different geographical locations: on the left we see a shot of the ocean taken on a beach in Chennai and on the right, we see a shot of a sugarcane field, taken in Tongaat South Africa, a rural town along the Indian Ocean, historically associated with Indian indentureship. The suspended masked figure functions as a representation of Africa. Africa is the point of convergence; every photo in this assemblage touches Africa and is touched by Africa. The portrait of an Afro-Indian family is the only photo in this assemblage that bleeds into the others suspending within the frame of this image the various visual elements and the different geographic, historical, spatial, and temporal moments this image attempts to capture.

By placing the photos of the ocean and the sugarcane side by side, I was interested in exploring the dynamics of migration and what it meant to create “home,” “family,” and “identity” in Africa. The oldest woman in the portrait—seated in the center of this image—arrived with her husband and her two daughters, who stand at her sides, as indentured labourers. This family was indentured to a coal mine (Elandslaagte Collieries) close to a town named Ladysmith. As you gaze at the visual assemblage, two ethnographic images taken from the book The People of India become visible—one of a man and a woman titled “Hindoos of Low Caste Vagrants, Delhi” and another of two men titled “Low Caste Hindoos, Bihar.” The people in these images appear as ghostly shadows; a reminder of the dynamics of caste and social standing in India. I wondered how caste translated amongst the indentured against an already well-established racial order in Southern Africa. For me, the juxtapositioning of the family portrait and the ethnographic images speaks to the power of the family portrait to fracture and return the ethnographic gaze. Through the family portrait, which I understand, following Tina Campt, as a performative practice rather than an objective documentary record of a particular place, time, and people, we can read the desire for stability, continuity, and familial intimacy.[7] As an assemblage, this image at once captures and complicates the process of making “home, kin, and community” by exploring the dynamics of migration, history, diaspora, and race.

Deepali Dewan is the Dan Mishra Curator of South Asian Art & Culture at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, and editor of the special issue “Family Photography,” Trans Asian Photography Review (Fall 2018).

Thy Phu is a Professor of English Studies at Western University, and Principle Investigator of The Family Camera Network Project.

Jordache A. Ellapen is an Assistant Professor of Feminist Studies in Culture and Media in Women and Gender Studies at the University of Toronto.

REFERENCES

- Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008).

- Interview with Michael D’Souza by Deepali Dewan, July 15, 2019. Courtesy the Family Camera Network, Royal Ontario Museum collection.

- Michael recalled later that he was mostly referring to his long hair and the jacket he wore, which was from Karachi.

- Richard H. Saunders, American Faces: A Cultural History of Portraiture and Identity (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 2016).

- Interview with Lu-Thai family by Thy Phu, October 11, 2016. Courtesy the Family Camera Network, Royal Ontario Museum collection.

- This image is part of my ongoing digital assemblage project “Queering the Archive: Brown Bodies in Ecstasy,” where through digital technologies I create visual assemblages to examine race, migration, history, memory, and sexuality in the South African context. The photos used in this project are drawn from my own family albums. For more information on this project see “Queering the Archive: Brown Bodies in Ecstasy: Visual Assemblages and the Pleasures of Transgressive Erotics,” in Scholar and Feminist Online (Special Issue, Afro-Asian Feminist and Queer Formations), 14, no. 3 (2018).

- See Campt, Tina. “Family Matters: Diaspora, Difference, and the Visual Archive,” Social Text 27, no 1 (98) (2009): 83- 114; Fleetwood, Nicole. “Posing in Prison: Family Photographs, Emotional Labor and Carceral Intimacy,” Public Culture 27, no 3. (2015): 487-511.