The Residents of Malcha Mahal, Delhi

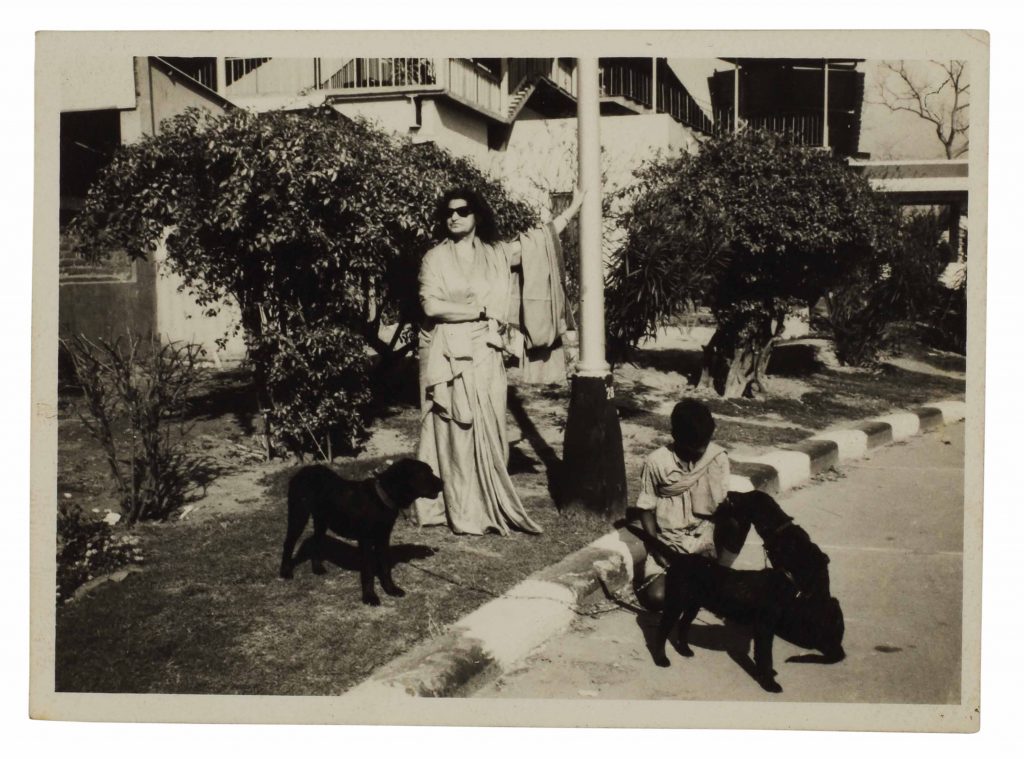

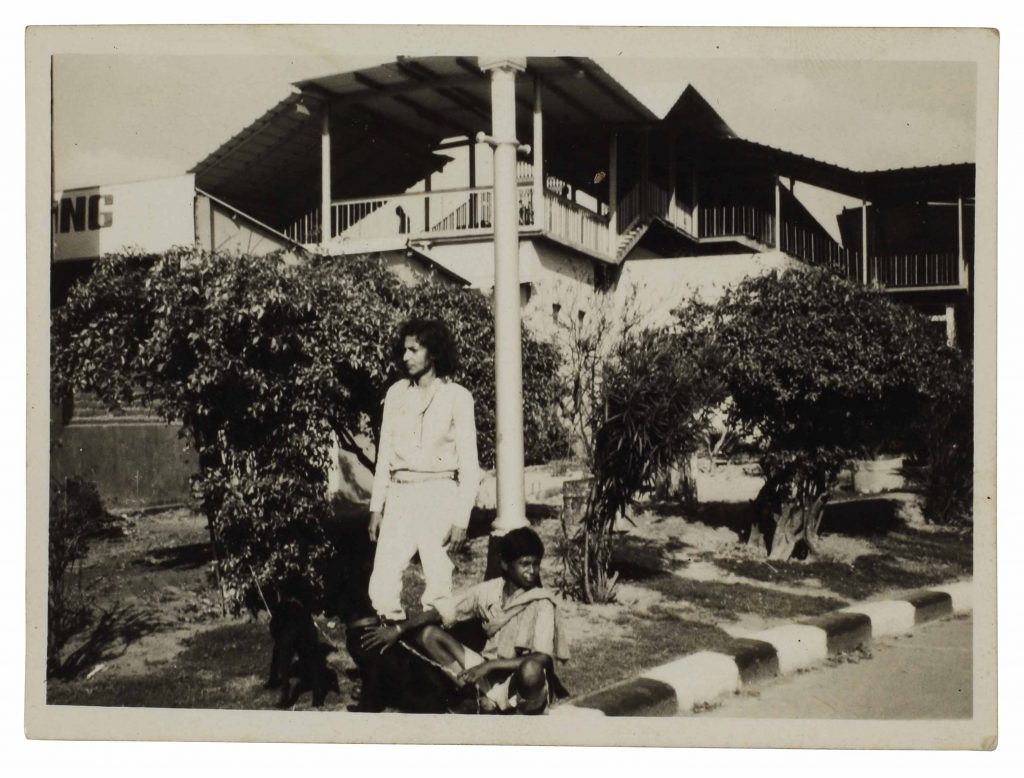

Left: Wilayat and Cyrus outside of Malcha Mahal. c.1990. Photo Negatives; Middle: Sakina in the first class waiting room at the New Delhi Railway Station. c.1980. Archival photograph; Right: Sakina. c.1965. Archival photograph.

I should start out by saying that the family’s history remains mysterious; I cannot say that I entirely solved the puzzle, which spans seventy years, three generations, and three continents. They took great pains to cover-up their background. However, I was able to establish some facts.

Wilayat Malik and Inayatullah Butt were of Kashmiri origin, and grew up in the walled city of Lahore. Wilayat was Inayatullah’s second wife. She was very young, still in her teens, when they married. She moved with him to Lucknow, where he occupied a prestigious position, as assistant registrar of Lucknow University. He was later promoted to the post of registrar, apparently the first Muslim ever to occupy that post. I believe she bore him five sons – Zahid, Khalid, Shahid, Tariq, and Mickey (I think his legal name was Asif) – and a daughter, Farhad, known as Baby.

But the family’s story was violently disrupted by the Partition. In 1947, after what the family members describe as an attack by a group of young men on Inayatullah, the family left Lucknow for Karachi, where Inayatullah was offered the post of Secretary of Pakistan Aviation, Ltd.

Inayatullah died in 1951. From this point onward, the fate of the younger children was propelled by their mother, who was increasingly at odds with Pakistani authorities. Wilayat was a proponent of Kashmiri independence, and an ardent, passionate activist. In 1954, she publicly confronted Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra over the fate of Kashmir, after which, I believe, she was arrested. Various members of the family confirmed that she was committed for six months to a mental hospital in Lahore. Later, petitioning the Indian government for asylum, she said she was subjected to “inhuman tortures” at the hands of the authorities.

In 1962, she took her youngest four children and returned, by ship, to India, where she settled in Srinagar and set about petitioning for the right to resettle permanently. The oldest among them, Shahid, left the family and returned to Pakistan. Wilayat was granted assistance by a friend, G.M. Sadiq, who was chief minister and then prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir, and India granted her the right to remain on a year-to-year basis “subject to good behavior.” At this point, she began to introduce herself as the begum of Oudh, and insisted that her children could not interact with commoners. They remained in Srinagar until the early 1970s, leaving for Lucknow and Delhi around the time of Mr. Sadiq’s death. One of her sons, Tariq, also known as Assad, did not accompany them, but remained in isolation in Srinagar and died there, alone.

From that point forward, the family’s activities can be traced through the accounts of journalists. They were known as Begum Wilayat, Prince Ali Raza, and Princess Sakina. They aroused much sympathy among U.P. politicians, who tried to offer them assistance, but Wilayat rejected their offer of a house in Lucknow. They stayed briefly in Lucknow, and then settled at the Delhi Railway station, where they remained, on and off, from the mid-1970s until 1984, when Indira Gandhi granted them the use of Malcha Mahal. All three remaining members of the family died in the hunting lodge.

– Ellen Berry

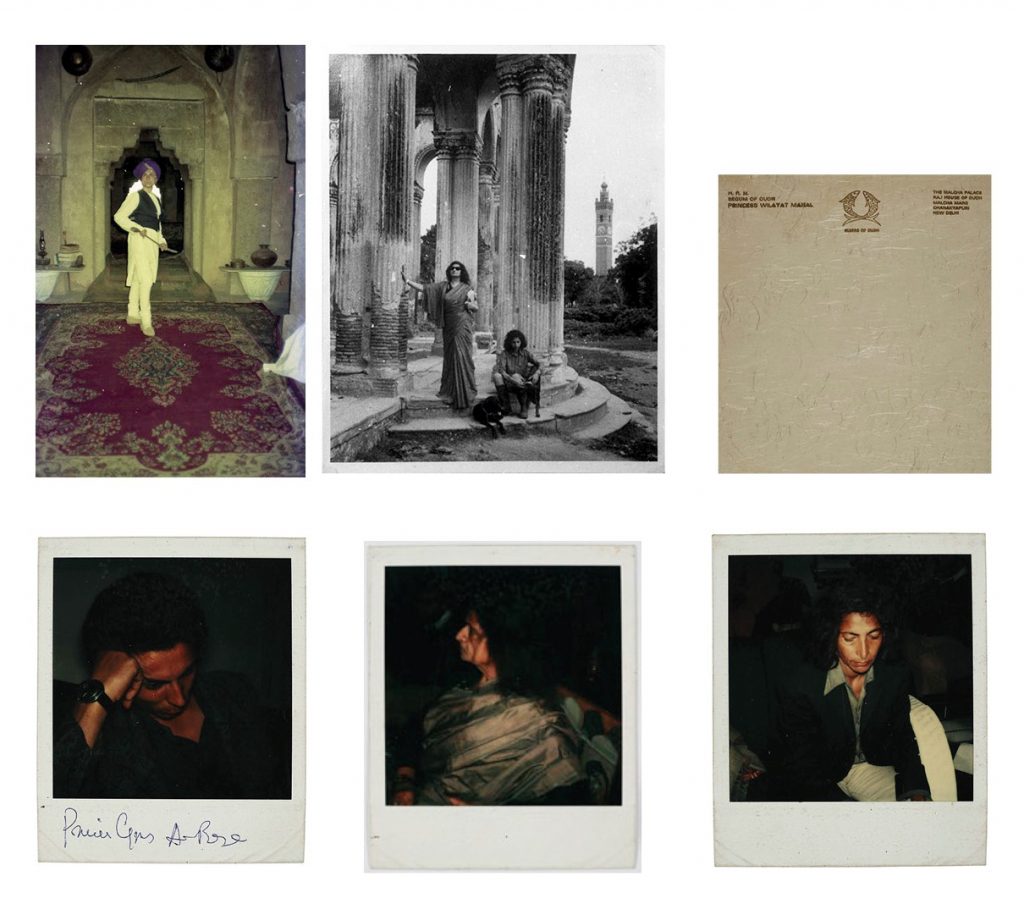

Upper Left: Cyrus in the entrance hall of Malcha Mahal. c.1985. Archival photograph; Upper Middle: Wilayat and Sakina, Lucknow. c.1975. Archival photograph; Upper Right: Personalised Stationery of the Rulers of Oudh. Archival Paper; Lower Left: Cyrus. c.1980. Polaroid print; Lower Middle: Wilayat. c.1980. Polaroid print; Lower Right: Sakina. c.1980. Polaroid print.

- How did you get involved with this fascinating story and what were your initial thoughts and ideas before and while going into the Malcha Mahal?

In February 2015, on a walk through the Ridge Forest in Delhi a friend told me about the Prince and Princess of Oudh. They had been living a mysterious, secluded life in a haunted ruin. My friend told me about how they had lived at the railway station for ten years and about their struggles to get recognition for their royal descent. Their life story was by far the most extraordinary I had ever come across. As a photographer I had spent years capturing people and places, and the relation between the two. This story was different. I thought there would be great visuals here; a centuries old ruin with weathered, stubborn people. I was thinking about the diffused Delhi light and how beautiful it would reflect on their royal artefacts and faces. However, I wasn’t prepared for the emotional impact the meeting with Cyrus would have on me and the complicated nature of the relationship that ensued.

- As the family has been photographed over the years by international journalists and this material and their story been made public in an extensive way, how does one negotiate the material as a living family archive, as opposed to it being a historical archive and news story?

For decades the Royals of Oudh have touched a nerve of many. After Cyrus passed away, a journalist’s obsession to find out who they really were fuelled the fascination that went around the world. As the truth of their identity comes to light, through the material and stories that remain, we are confronted with our own beliefs of identity and recognition. In what ways do they affect our own relationships and sense of self?

The history of the Royals of Oudh also portrays a cycle of abuse and damage inflicted by one generation on to the next. It begs the question: How could they have escaped from the mental illness and brainwashing that perpetuated these beliefs? Was the creation of their own reality and the absolute refusal of any challenge a part of it?

What remains is not just a historical archive, but scenes from a crumbling existence. How did the Royals of Oudh archive themselves? What does it say about their search for meaning and selfhood, their claim to fame, holiness, and a place in the history of India? Their story lives on and could not be more relevant in a country riven by questions of identity and belonging.

“We are and were not free with each other very formal reserved in every way perhaps this has been inherited naturally in our blue veins.”

– Princess Sakina

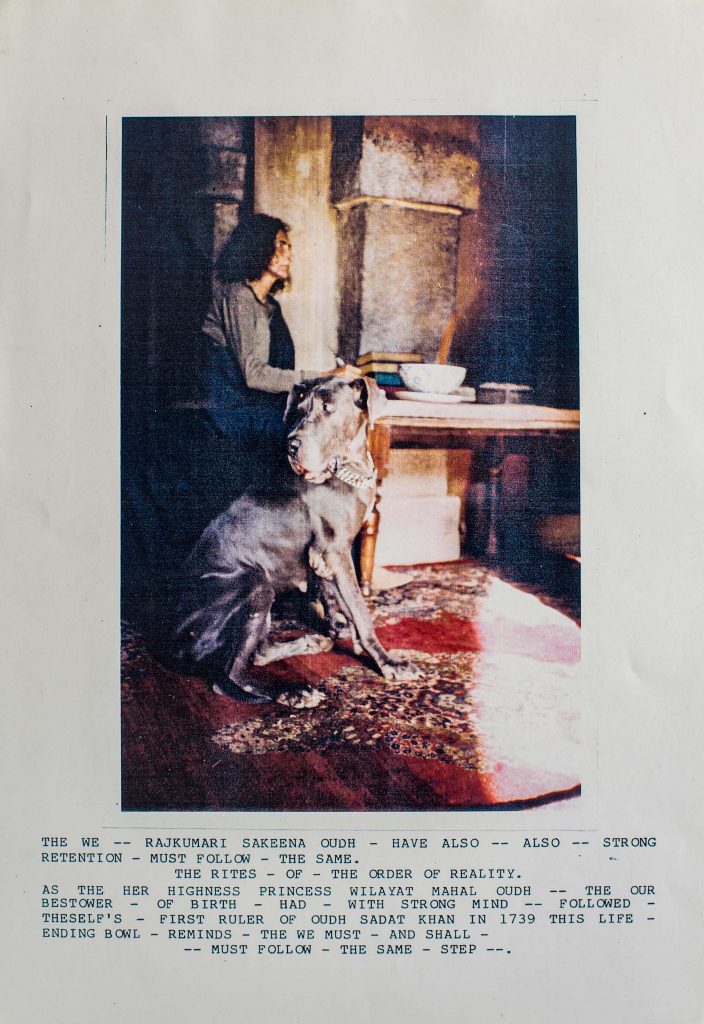

Page from the book “The Rulers of Oudh,” by Sakina. c.1995.

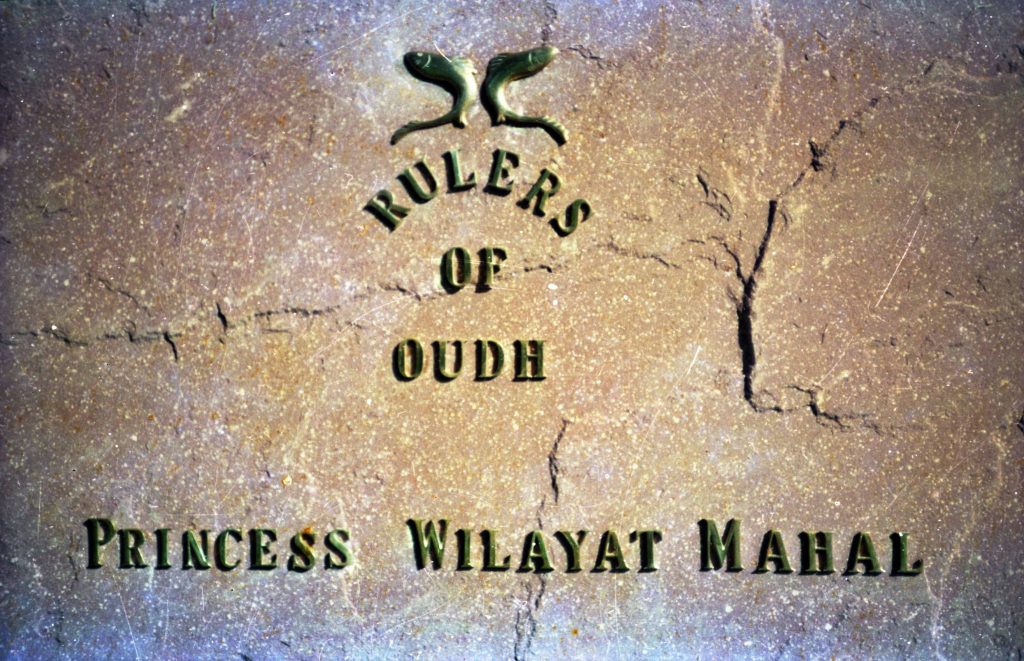

Entrance sign of Malcha Mahal, Page from the book “Rulers of Oudh,” by Sakina. c.1995.

It is the viewer’s choice whether the family archive is alive. It all depends on the willingness to answer the question about how we construct an idea about who we are, and whether we are open to change this when because of these ideas our relationships with others and the lives we could have lived fall apart.

- How do you address the process of making documentary photographs? Could you talk about your perspective on the elaborate fiction surrounding the family and how that may have affected you?

When I first visited Cyrus, I was mainly focused on photographing him and Malcha Mahal. I already had visuals in mind, his royal features, Rembrandt-esque lighting, and splendorous artefacts. My idea on how to document the Royals of Oudh was to get a portrayal of how Cyrus lived and how he and his family had been able to keep up their royal presence under very harsh circumstances. This was the only truth I thought I could document, as I felt photographing Cyrus’ from another perspective was too unclear in order for it to represent a form of truth. Cyrus was very mysterious about his life and history, but little by little he showed me family photos and other areas of the palace. He asked me specifically to help him digitally archive his photos, which I did. He felt the same urge to archive his life, his history, just like his sister had. Cyrus was such a lonely man. His sister had recently passed away and he was desperately holding on to the story that had shaped his life and identity. The craziness that had given meaning to his cruel life. I could see his hunger for normality.

It wasn’t after Cyrus had passed away and I had access to more material that I got more insight in their personal lives, thoughts, and feelings. This fascinated me much more than any of the claims the Royals had ever made. I decided to focus my work on Sakina’s diary, their constructed history, and photos. My own images show how place and objects lose their meaning once the constructed ideas about them crumble. After finding out more about Cyrus’ identity and reading the documents and Sakina’s book, the question of whether they were royal or not didn’t even matter to me anymore. I started to see Cyrus’ personality through the documents, his struggles, his arrogance, and the manipulation he had suffered. I discovered a woman who had loved him, a brother who had supported him, a deep love for a sister he hardly spoke to and a loneliness and confusion that is hard to grasp.

When thinking about how the elements in the fiction surrounding the family determined the documentation of the story of the Royals of Oudh, I realise that it is the context within which a photo is produced and consumed that shapes the meaning of it. It took quite a few instances of “viewer’s rage” to become aware of my own paradigm from which I had been reading and documenting the history of the Royals of Oudh. As our understanding of the reality of the Royals of Oudh grows, we need to calm our rage, grasp the opportunity to look at the materials from a new perspective and honour their extraordinary lives.

Through what is left, I am trying to see glimpses of the real Cyrus and Sakina, their struggles, loves, and dreams. This is what documentary photography is all about, experiencing the change in perception of the work, discovering that it is not even about what is truth or not, but by being touched by its changing reality in a profound way.

Leonie Broekstra is portrait and documentary photographer. Her work explores how meaning is given to places, objects, and living beings and how this changes over time. She studied photography at the Open College of Arts and is currently based in New Delhi.

Interview with Anisha Baid

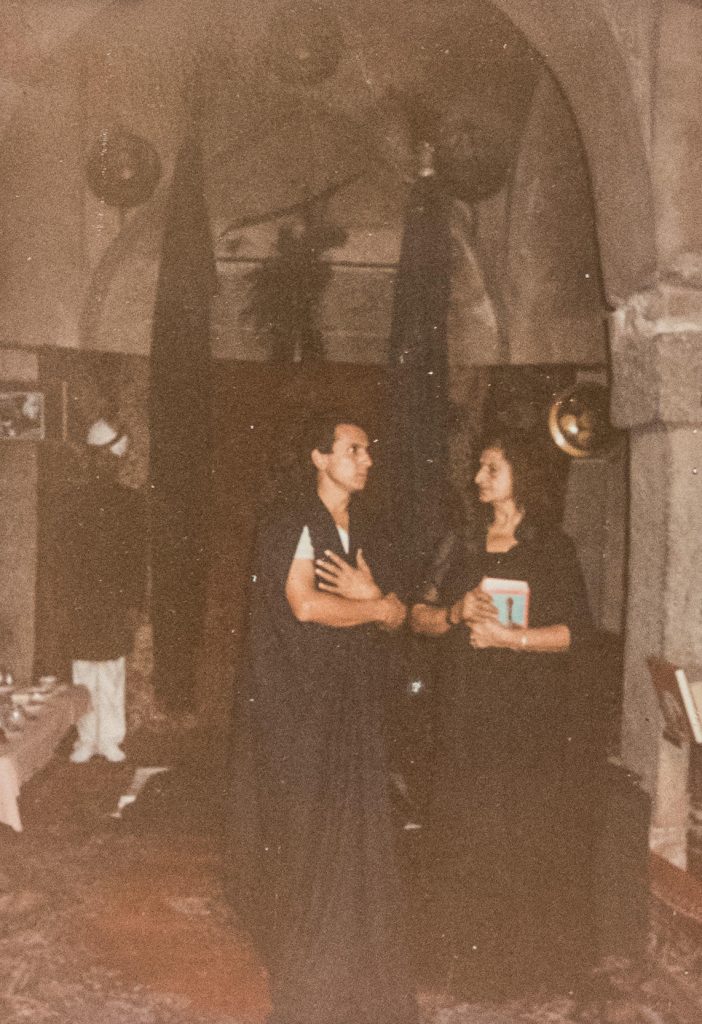

Cyrus and Sakina, Malcha Mahal. c.1990. Archival photograph.

Leonie Broekstra, Embossing stamp of the Rulers of Oudh. November 2017. Digital.

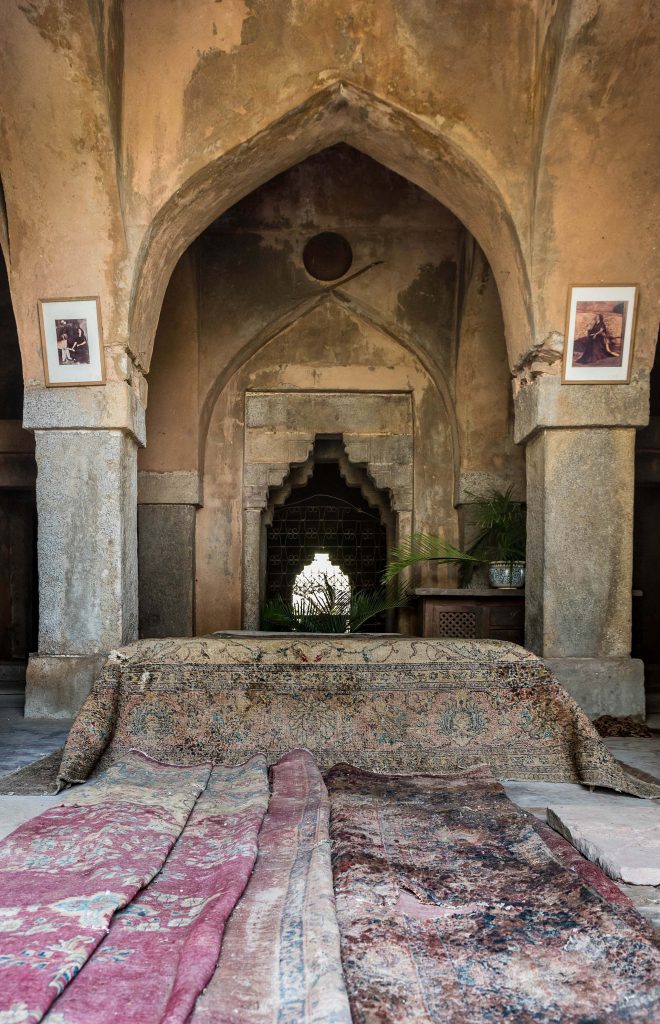

Leonie Broekstra, Interior of the Malcha Mahal entrance hall. February 2017. Digital.

Leonie Broekstra, Ransacked cupboards after Cyrus’ passing. November 2017. Digital.

Leonie Broekstra, Interior of the Dining Hall after Cyrus’ passing. November 2017. Digital.

Leonie Broekstra, Table set for Wilayat. November 2017. Digital.

Dogs. c.1990. Archival photograph.

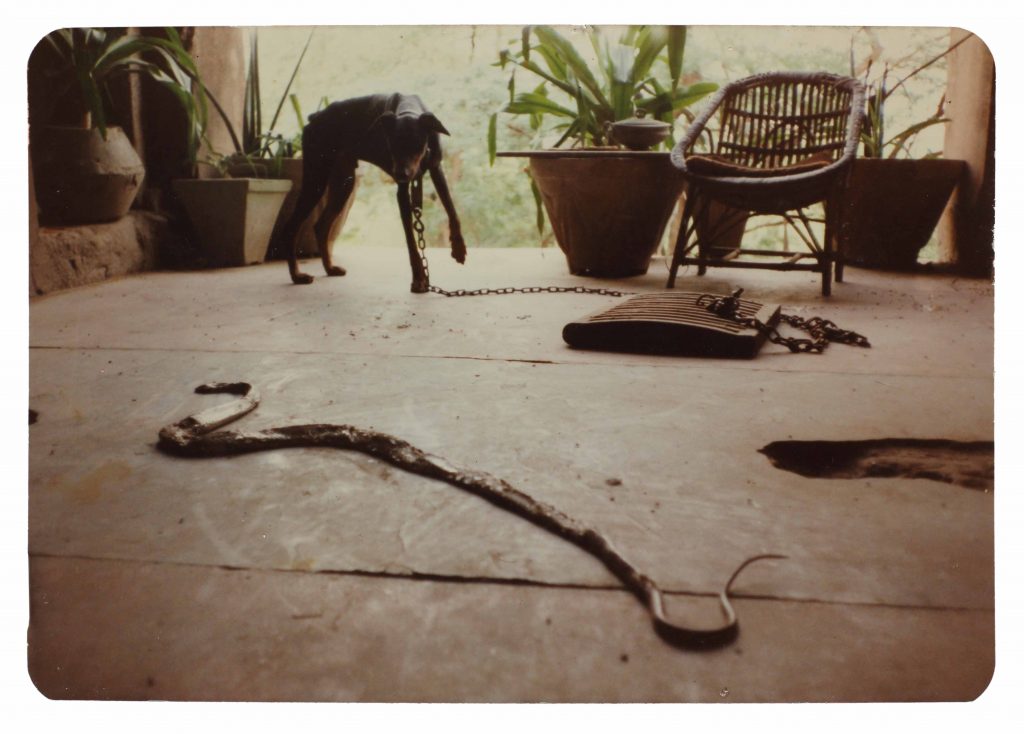

Dog and dead snake. c.1990. Archival photograph.

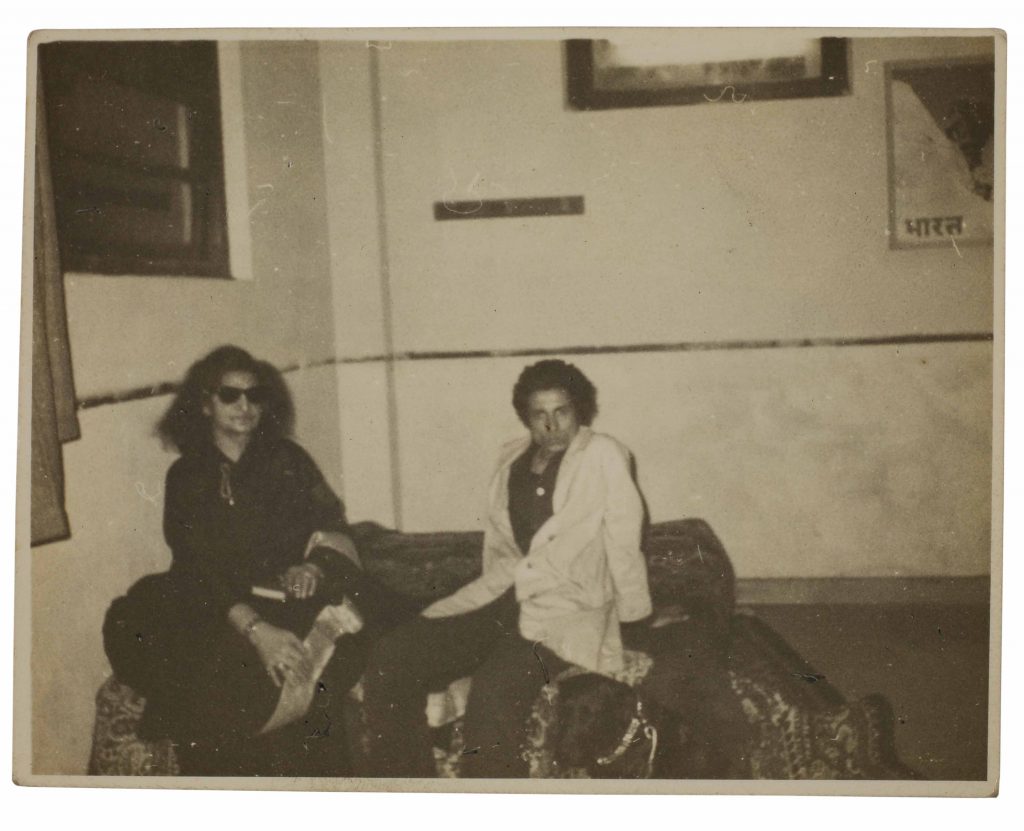

Wilayat and Cyrus in the First Class Waiting Room at the New Delhi Railway Station. c.1980. Archival photograph.

Wilayat. c.1970. Archival photograph.

Sakina. c.1970. Archival photograph.

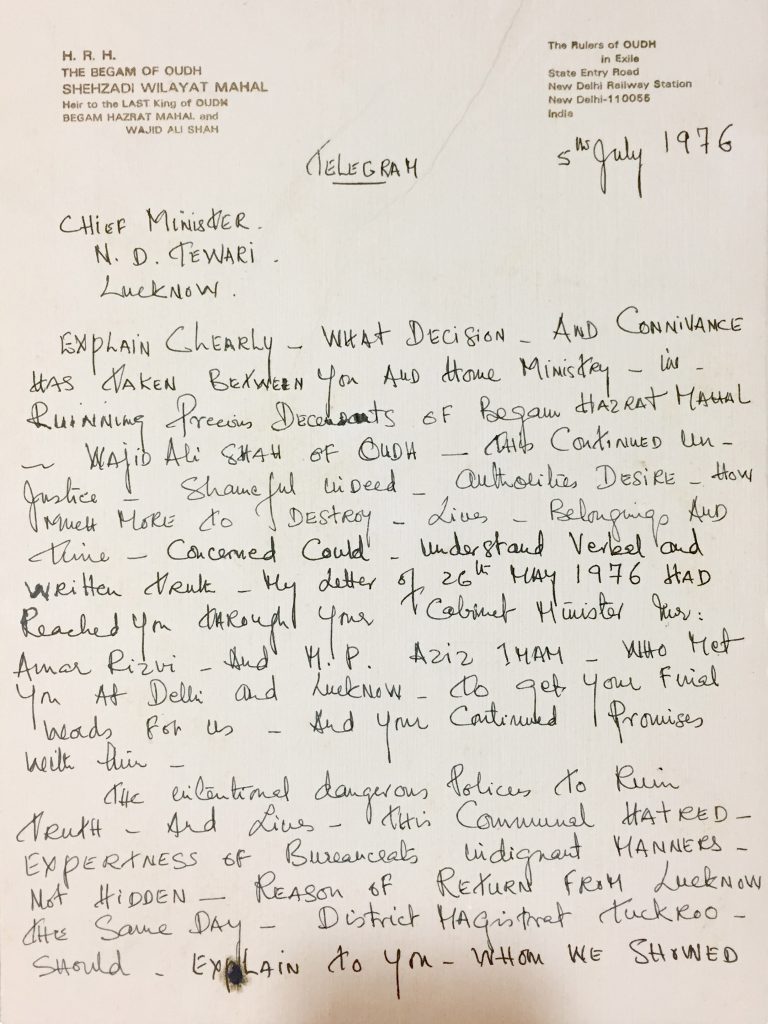

Letter from Wilayat to Chief Minister Chewari. July 1976.

Letter from Wilayat to Chief Minister Chewari. July 1976.

Watch Leonie talk about The Residents of Malcha Mahal, Delhi: