1943: Sunil Janah’s Famine Photographs

Neither life nor death, it is the haunting of the one by the other … Ghosts … 1

The images of the Bengal Famine (1943-44) produced by photographer Sunil Janah and the artists affiliated with the Communist Party of India (CPI), represented the first attempt in the history of modern India to expose the plight of refugees and visually inspire resistance for political expediency. During the final decade of India’s battle for freedom in which genocide, famine, war, and populist politics were defining factors, these documentary images constitute one of the most compelling visual attempts to create and mobilise a mass public. Whatever threats were posed to the colonial order by these images of “bare life,” what is interesting to note is the silence in the national narrative in regards to these works. This tenuous and fragile legacy has barely been acknowledged in historical accounts of Indian art, with art historians skirting around it.

In 1945, as World War II drew to a close, Britain’s brief flirtation with the CPI came to an end. A redundant ally in the fight against fascism, CPI members “were promptly told where they belonged.2 Janah continued to photograph political events for the Party up until 1947, when at the Second National Conference of the CPI, leading members declared the bankruptcy of Independence. Moving from the People’s War line back to the strategy of anti-imperialist struggle, the CPI Central Committee described the postwar years in India as “the period of unprecedented opportunity to make the final bid for power.”3

Mindful of the Red Army’s successes, the victories in the People’s Liberation War in China, and the armed struggle for Independence in Southeast Asia, the CPI surmised that a greater degree of insurgence against British rule in India was all the more justified. Party officials were convinced that the interests of landlords and princes were inextricably entangled with the Empire and suspected an impending alliance between “British big business and their Indian brothers.” For this reason, the CPI sought to unleash agitation on a national scale to unite the industrial workers with the peasants.4 In 1947, however, on India’s attaining Independence at the cost of the brutal Partition, the unrest ended.

Following further upheaval in the CPI in 1948, the Party splintered; former General Secretary P. C. Joshi and several members, including Janah, were expelled.5 Their dismissal marked the dissolution of the CPI and the collapse of a movement that had radically transformed the meaning and social function of art. As Janah would later recount:

For many of us, the disastrous Partition of our country, and the murderous communal riots that accompanied India’s Independence, were a heartbreak from which we never recovered. Independence had not brought any beginnings of a new era, nor any remarkable changes in the country, not even the promise of any. I did not rejoin the Communist Party, nor did I want to join any other party. I felt that I could never be a political activist again […] Independence did not, of course, bring relief to the appalling miseries of our people, but it happened to coincide with the termination of my Communist Party days and relieved me from the onerous task of recording further miseries.6

A politically disillusioned Janah returned to Calcutta in 1948, where he set up a private commercial photographic studio. Completely dissociating himself from Party politics, Janah “armed” himself with a Linhof Technika, adding three lenses, and began to work for the Government of India.7 Under Prime Minister Nehru’s drive for rapid industrialisation during the 1950s, Janah found himself covering the country’s major industrial and development ventures. The projects came under the Government’s first Five-Year Plan, Nehru’s “new temples” of modern India. The Hindustan Steel Works, the first public sector undertaking in the steel industry, commissioned Janah to photograph numerous development projects: at Durgapur in West Bengal, Rourkela in Orissa, and Bhilai in Central India amongst others. The function of photography here was no longer to critique poor labour conditions and the plight of workers, but redirected toward producing lavish marketing brochures to attract interest from potential investors. The figure of the worker appears to be entirely subordinated to the machine.

Up until the early 1960s, Janah continually engaged with heavy industry, working for leading Indian industrialists and businessmen such as J. R. D. Tata and G. D. Birla, and for British mercantile firms. In photographing the mining of coal, manganese, bauxite and aluminium, he produced images celebrating the economic foundations of post-colonial India.

In its latter incarnation, documentary photography acquires a different propagandistic purpose. Reminiscent of Margaret Bourke-White’s industrial photography, Janah glamorises machines and industrial prowess at the expense of the workers. The industrial landscape is a “photographic paradise,” remarked Bourke-White of the Cleveland Otis Steel Mills in the early thirties.8 Similarly, during her sojourn in the Soviet Union, “the land of embryo-industry,” Bourke- White conveyed the quasi-religious machine fervour of the Five Year Plan, fusing photographically man and machine in a romantic utopia.9 Janah too delights in the novel spectacle of smokestacks, derricks and titanic machinery. In the photograph There She Blows Setting the Jamshedpur Sky Aglow, commissioned by the Tata Iron and Steel Company in 1957, Bihar, two monumental Bessemer converters emit toxic clouds of smoke. The converters dwarf the two workers depicted in the background, their faces blurred.

The contrast between the scale of the human figure and the machine is further accentuated in the photograph Steel Smelting Shop, Tata Iron and Steel Works, Jamshedpur, of the same year. Singling out the steel smelting area of the factory, the viewer is titillated by the play of light generated by the repetitive crates positioned on the ground. The titanic arm of a machine steers a colossal vessel along its tracks, moving towards a Lilliputian worker with his Nehru cap. The spectral figure of the factory worker resurfaces in the highly choreographed photograph Women Workers During Construction at a Thermal Power Plant in Bihar, one of Independent India’s First, 1950s. Female adivasi (tribal) workers descend a vertiginous staircase balancing baskets on their heads, their bodies profiled against the stark diagonal of the scaffolding.10 The precarious and backbreaking work of women is beautifully packaged for the viewer and the potential investor.

Towards the end of his photographic career, an embittered Janah began to photograph India’s adivasi communities. Meeting the well-known British anthropologist Verrier Elwin, with whom he formed a lifelong friendship and association, Janah spent much of his free time escaping the narrow bounds of cheerless, staid respectability in search of the communal experience of tribal life.11 But it appears that Janah’s own primitivist fascination with vanishing pre- industrial humanity would be fuelled by the very forces of development that would eventually annihilate this humanity. This is particularly so in the case of adivasi men and women, recruited as industrial labourers in Nehruvian India and brutally dispossessed of their lands through the construction of factories, damns and mines.

Janah would later recall in his memoirs the arresting sight of “very modern industrial structures being built manually by primitive villagers and tribals carrying cement mixtures in pails on their head at the worksites, where giant steel piles were being driven into the ground by even bigger machines, and monstrous earth-moving machines were roaring around.”12 The figures photographed by Janah rarely resonate with the heroic iconography of the proletarian, industrial worker celebrated through Communist print currencies – an iconography to which Janah had been drawn. The machine, in the case of these photographs, reduces the workers to minute, barely formed humans; the rhetorical power of these images lies more in their evocation of a development that is yet to come through the technology of photography.

Janah’s glorification of the machine and upholding of the extractive post-colonial economy at the expense of the prosaic worker, could be seen as reinforcing the sexual fetishisation of adivasi women as in the photograph Younger of the Two Sisters from Poonani Village Whom I Spotted on a Beach. They were Picking Sea Shells for a Lime Factory.13 The image depicts an adolescent girl who closes her eyes as she coyly offers her breasts to the voracious gaze of the camera.

From an overview of Janah’s career as a photographer, we can see him moving from the turbulent arena of pre- Independence India to the intimate, personal space of the studio, and finally towards nature, a realm seemingly untainted by industry. Whether Janah, in his documenting of idyllic tribal life, was unconsciously shouldering blame for his political disillusionment, is something that enhances the mystery around him.

Under the leadership of Joshi, the CPI played a crucial role in providing food, shelter and medical aid to the victims of the Famine of 1943. Janah’s photographs contributed to this surge of relief activity during the emergency years of World War II. For this reason they represent a peculiar moment in the history of Indian photojournalism, a history marked by the CPI’s paradoxical endorsement of the People’s War line. Though the social welfare operations backed by the CPI challenged the hegemony of the Indian national movement during the 1940s, they offered no genuine political alternative. As Joshi would later put it: “Ultimately, we failed in our basic task, namely, to explain the roots of the problems which confronted the masses.”14 Unable to comprehend and critique the long-term economic, social, and political factors which had made such a society so peculiarly fragile and vulnerable, the CPI failed to explain the famine phenomenon: what had marked its onset, its duration, and future, grim incarnations. Janah too, while a committed Communist, was aware that mere act of taking photographs would not change the course of events:

I do not relish, to this day, the fact that I earned my early fame from the grim business of photographing the starving, the dying and the dead victims of a dreadful famine. Joshi had impressed upon me, however, the need for bringing this hidden tragedy to light, and my only consolation had been that our reportage brought the unfortunate victims of this man-made famine some long-overdue attention, and may have prodded relief efforts.15

Janah’s inability to perhaps radicalise his subjects can be linked to the CPI’s precarious allegiance with the British during the war.16 The latter prevented the Party from embracing a truly revolutionary practice. As Joshi would later state (in 1965): “The historic tragedy of the Indian Revolution was that the Indian Communists were too blinded by Stalinist dogmatism to make a positive contribution in shaping the course of events.”17Janah’s disaffection with party politics explains his reticence to describe some of these photographs. He further recounts:

Photographs cannot make a political statement directly, but they can arouse emotions that can be harnessed for social and political causes. I did that for a time, and then, although politics was never expunged from my thoughts, I settled instead on taking photographs with no other purpose than that of pleasing myself and, perhaps, others too. These photographs captured moments from the history of our people and from the events, experiences and encounters of my lifetime, and they may have, in Susan Sontag’s words from one of her essays on photography, “conferred on them some kind of immortality.”18

Adapted from Art and Emergency: Modernism in Twentieth- Century India. Published by I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. 2018.

■

Emilia Terracciano is a Bowra Junior Research Fellow in the Humanities at Wadham College, Oxford University.

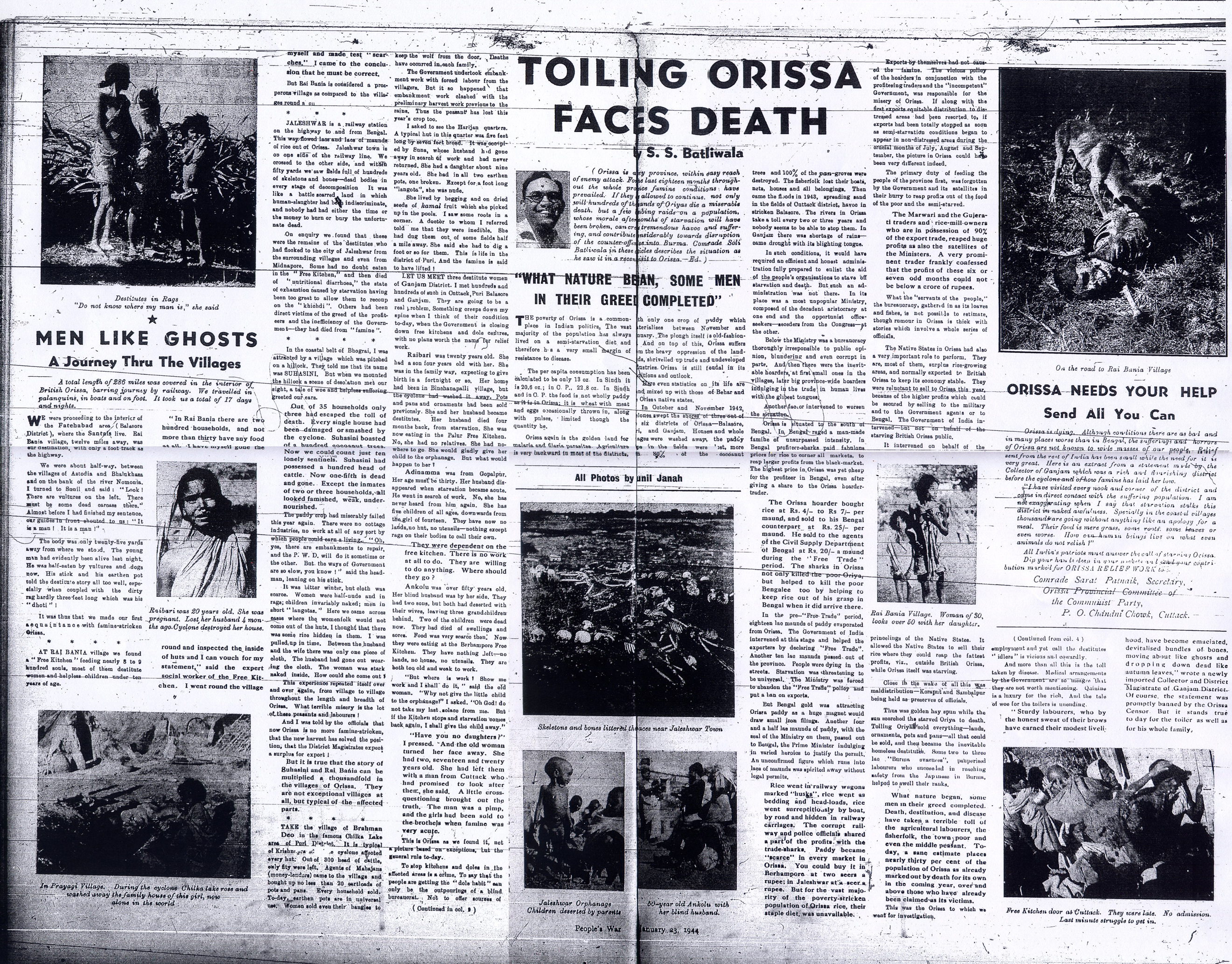

Janah’s firsthand experience of the famine culminated in a photo essay published in People’s War in November 1943, entitled ‘Toiling Orissa faces Death’. The photo essay comprised a written report by party member S. S. Batliwala, interlocked with Janah’s black- and-white photographs.

Janah’s firsthand experience of the famine culminated in a photo essay published in People’s War in November 1943, entitled ‘Toiling Orissa faces Death’. The photo essay comprised a written report by party member S. S. Batliwala, interlocked with Janah’s black- and-white photographs.

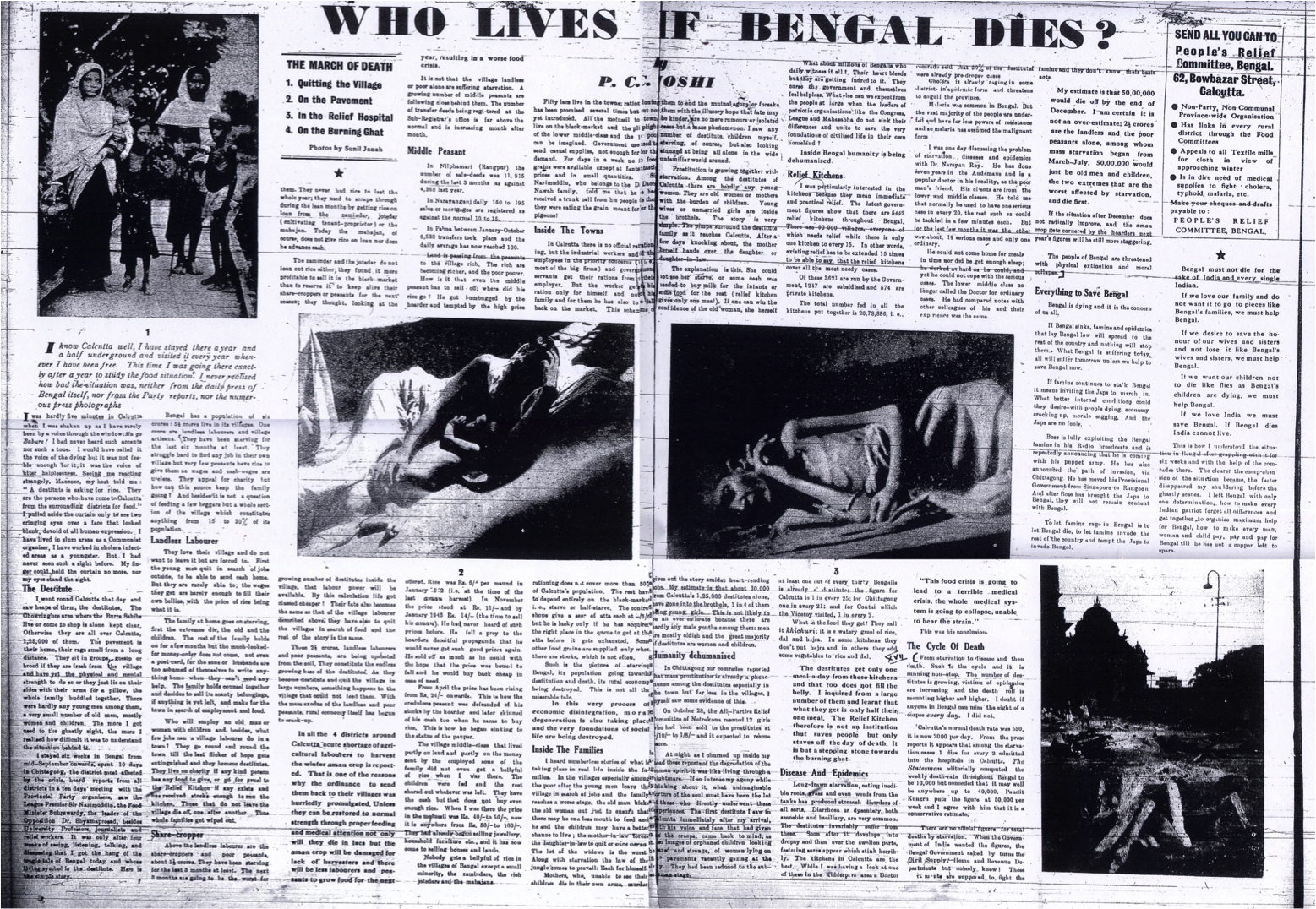

In the same year, another photo essay entitled ‘Who Lives if Bengal Dies?’ was published in People’s War. The four-sequence montage sums up with bleak realism the rural migrants’ dispiriting march unto death.

In the same year, another photo essay entitled ‘Who Lives if Bengal Dies?’ was published in People’s War. The four-sequence montage sums up with bleak realism the rural migrants’ dispiriting march unto death.

Notes

1. Jacques Derrida, ‘The deaths of Roland Barthes’, in H. J. Silverman (ed), Philosophy and Non-Philosophy since Merleau-Ponty (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1997), pp. 266-7.

2. Janah, in conversation with the author (12 March 2009).

3. Habib, ‘The Left and the National Movement’, p. 25.

4. Ibid., p. 26.

5. Under the (Stalinist) leadership of B. T. Ranadive, Communists resolved to continue fighting for a ‘free India’. Ibid., p. 28. In 1964, the Party split into two: The ‘Communist Party of India (Marxist)’ (CPM) and the Communist Party of India (CPI). See Gupta, Communism and Nationalism in Colonial India, 1939-45.

6. Janah, Photographing India, pp. 36-7.

7. The same camera Bourke-White used during her travels in India. Janah, Photographing India, p.41.

8. Bourke-White, Portrait of Myself, p. 33. She writes: ‘To me, fresh from college with my camera over my shoulder, the Flats were a photographic paradise. The smokestacks ringing the horizon were the giants of an unexplored world, guarding the secrets and wonder of the steel mills. When, I wondered, would I get inside those slab-sided coffin-black buildings with their mysterious unpredictable flashes of l ight leaking out the edges?’

9. Barnaby Haran, ‘Tractor, Factory Facts: Margaret Bourke-White’s Eyes on Russia and the Romance of Industry of the Five-Year Plan’, Oxford Art Journal, vol.38, issue 1, 2015, pp.73-93.

10. For a different reading of this image, see Rebecca M. Brown, Art for a Modern India, 1947-1980 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), pp. 128-9.

11. Notable works are Verrier Elwin’s The Muria and their Ghotul (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1947), The Tribal World of Verrier Elwin: An Autobiography (London: Oxford University Press, 1964), The Baiga (London: J. Murray, 1939), and Leaves from the Jungle: Life in a Gond Village (London: John Murray, 1936).

12. Janah, Photographing India, p.41.

13. Photograph originally entitled: Malabar, Kerala, 1940s. Peasant Girl, Malabar Coast, Kerala 1945.

14. Joshi in Chandra, ‘P. C. Joshi and National Politics’, p. 250.

15. Janah, Photographing India, pp. 10-11.

16. For a compelling discussion on the relationship between photojournalism and fine art photography in the work of photographer Sebastião Salgado, see Julian Stallabrass’s essay ‘Sebastião Salgado and Fine Art Photojournalism’, New Left Review 223 (1997), p. 131. Stallabrass contends that in the case of Salgado’s photographs of the inhabitants of Sahel, there is great difficulty in successfully ascribing agency to subjects, since the latter’s sole preoccupation is the need to find food.

17. Joshi in Chandra, ‘P. C. Joshi and National Politics’, p. 263 [my emphasis].

18. Janah, Photographing India, p. 110 [my emphasis]. Janah is here referring to a passage from Sontag’s Preface to Don McCullin (London: Jonathan Cape, 2001), not paginated [my emphasis].