A Journey of Resistance: The Sahmat Collective

When Sahmat was formed in the emotional aftermath of Safdar Hashmi’s murder in January, 1989, it was decided at the very outset that it would be an artist-run collective and not an affiliate of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), although many in the founding group were Safdar’s comrades in the party. This decision has allowed Sahmat

the freedom to conceive and execute innovative projects, sometimes at lightning speed. Of course Sahmat could never have survived without the support of the CPI(M), its cadre and organisational affiliates. Its first office was located in the enclosed verandah of a flat allotted to the writers’ organisation of the party, and the current office is in the garage of a CPI(M) member of Parliament’s residence. Yet Sahmat’s independence from party diktat has allowed for the participation of people with varying political beliefs, all essentially progressive.

Art as activism in India was fostered mainly by the Communists in the 1940s. It was the vision of the General Secretary of the then undivided Communist Party of India (CPI), P. C. Joshi, that writers, artists, and performers should be involved in direct political action, which led to the founding of the Indian Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) in 1936 and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) in 1942. Both were directly affiliated to the CPI. In fact the party had set up a commune in Bombay of performers, actors, and writer members of IPTA and PWA, which functioned from 1943 to 1947—until the official ties between these organisations and the party were severed after Joshi was ousted from his position.

The event that led to the formation of IPTA and provided the motivation for its incredible reach across India was the Bengal Famine of 1942. It was also the famine that prompted Joshi to recruit two visual artists, the photographer Sunil Janah and the illustrator Chittaprosad, to work for the party’s newspaper People’s War, and move them from Calcutta to the commune in Bombay; their official affiliation with the party also ended in 1947 after Joshi’s ouster. But those five years of intense cultural action had a lasting impact on cultural developments in India after Independence. The idea of “Unity in Diversity”—of the unity of a people’s culture cutting across the multiple religious, caste, and class identities of the subcontinent—was propagated by the Communists in the 1940s. After the dissolution of IPTA in 1947 many of them moved to Delhi and found employment in various government cultural departments set up after independence, including All India Radio. It was through them that the cultural ideas of the left movement became central to the national cultural ethos of the newly independent, “Nehruvian” India.

Sahmat’s direct link to IPTA was through Bhisham Sahni, the writer, and Habib Tanvir, the theatre director. Both had also worked closely with Safdar Hashmi, and they served as the first and second chairpersons, in succession, of Sahmat. If the Bengal famine was a moment that galvanized IPTA, the demolition of the mosque in Ayodhya in 1992 played a similarly central role in Sahmat’s trajectory and led it into a more activist phase. It also served to broaden the base of the collective to include historians, archeologists, and social scientists. Sahmat’s Ayodhya initiatives and the attacks on them led to its national prominence in ways it had never imagined. By staying the course and keeping up the struggle and resistance through the arts, the collective has managed to survive and remain relevant.

Sahmat likes to define itself as a “platform.” Open-ended and inclusive, it has helped to create and maintain the space for cultural resistance. It is on this platform that the historian, even the archeologist, can be a cultural activist. With right-wing politics in India striving hard to restrict cultural space and freedom from within, and the equally massive assault from the globalised economic and mono-cultural interests coming from the outside, it has become even more crucial to defend the space of resistance.

Adapted from The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989, published by the Smart Museum of Art, Chicago 2013.

■

Ram Rahman is a photographer and a member of Sahmat’s founding group.

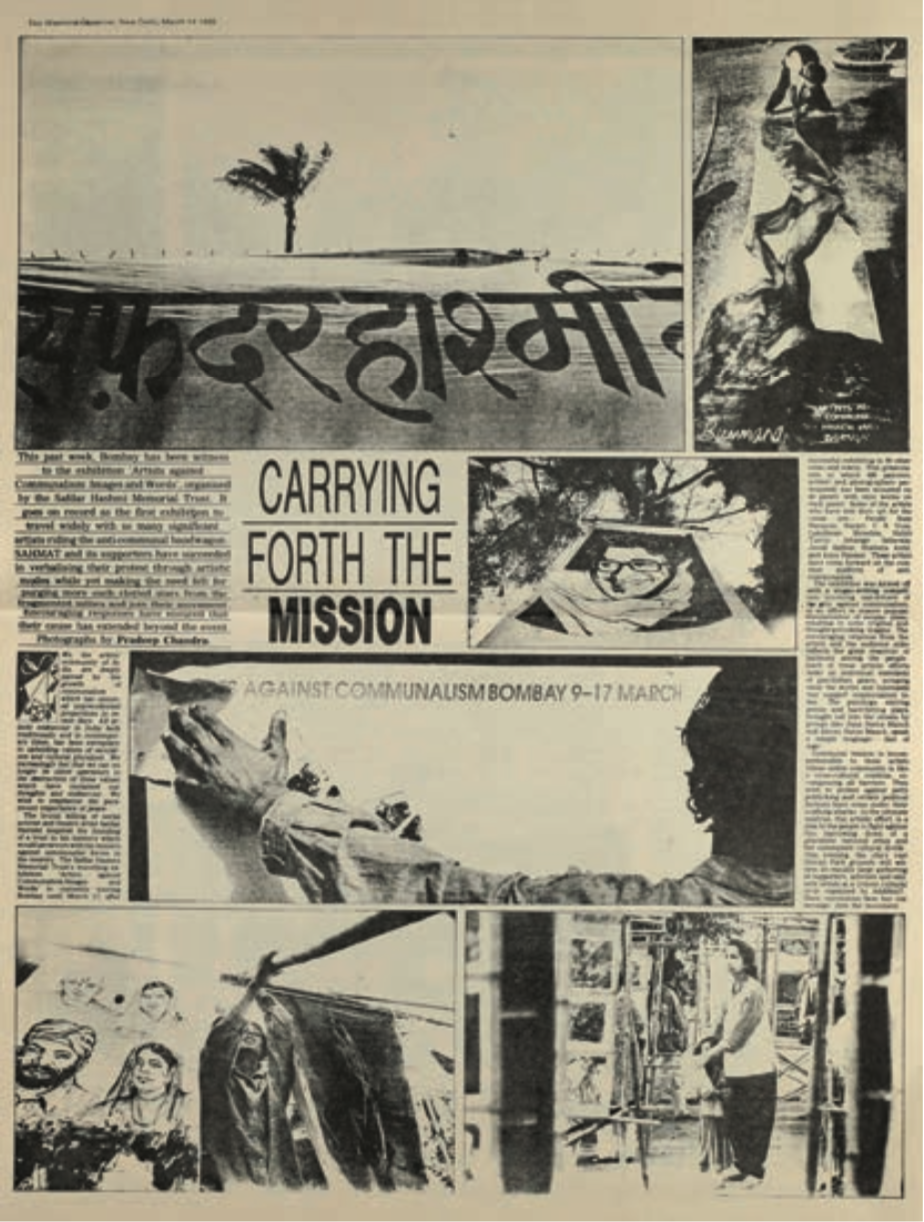

Page from Artists Against Communalism, Sahmat, 1992

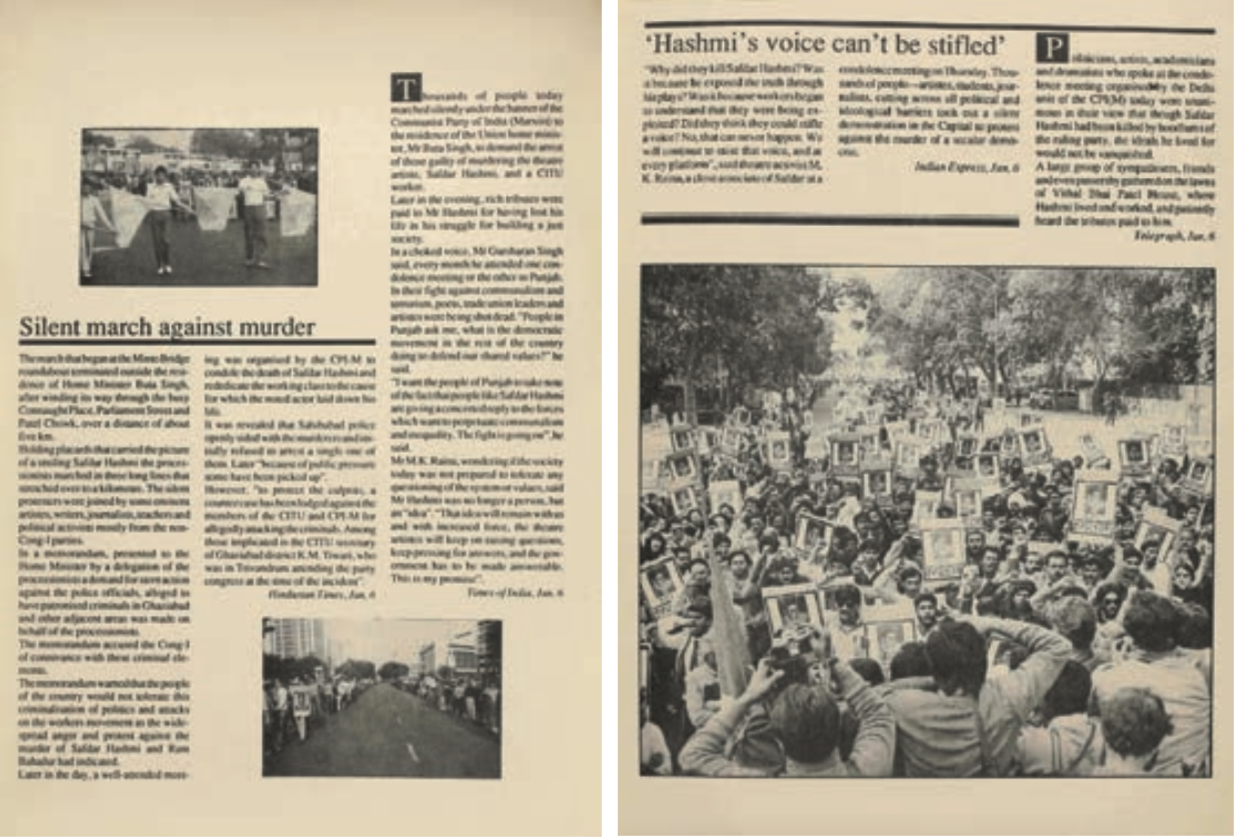

Spreads from Safdar, Sahmat, 1989

Spreads from Safdar, Sahmat, 1989

Safdar Hashmi: Performance of Aurat, Delhi, March 1979, 35 mm

Safdar Hashmi: Performance of Aurat, Delhi, March 1979, 35 mm

Left: Ratan Das, Mai Diwas ki Kahani, 1986. LIC parking space, Delhi, 35 mm. Right: Safdar Hashmi / Janam, Sati Virodhi Sangharsh Manch, 1987 Delhi, 35 mm

Left: Ratan Das, Mai Diwas ki Kahani, 1986. LIC parking space, Delhi, 35 mm. Right: Safdar Hashmi / Janam, Sati Virodhi Sangharsh Manch, 1987 Delhi, 35 mm