Adivaani: A Testimony of Resurgence

As Adivasis (tribal/indigenous), our faces, features and bodies hold the landscape of our lived-in experiences, identities, and struggles.

I bore and bear the stigma of Adivasi stereotyping. I spent my school years hiding from people and places because I became the personification of the inferiority that I was made to feel, internalising the inadequacies I was made to believe I had. Being dark-skinned and Adivasi—information I revealed as there was no reason to conceal my ethnicity—was enough to attract jibes, taunts, and jokes. I could not break through the external impressions of who I was to others to assert that there was more to me. My formative years were clearly the un-making of me.

The story of adivaani is an extension of my own. The becoming of adivaani is the becoming of me, and was born as the result of a threshold I had reached in my

lived-in experience of exclusion and discrimination as an Adivasi. Mine, though, is only a microscopic reflection of the dimensions that prejudice, injustice, violence, and subjugation play out in our everyday lives in addition to state- and corporate-sponsored crimes and neglect. From large scale “development” projects imposed on Adivasis

in places like Odisha, which amount to an invasion and dispossession of their lands and traditional culture, to the price Adivasis have paid for protesting for their right to life and livelihood, to being hunted as Maoists under Operation Green Hunt or Salwa Judum, the cost of being Adivasi is being an expendable, lesser citizen.

adivaani wasn’t something I prepared, planned, or had an idea about. It was something I strayed into when, in April of 2012, I attended a four-month-long publishing course while I was between jobs and had the time. I most certainly wasn’t planning on making a career in publishing.

The first month of the course was called “Publishing Lives,” and involved meeting the who’s who of the industry— national and international, mainstream and independent publishers, authors, poets, illustrators, and printers. We met publishers who exclusively issued writing by and for women, Dalits, or a particular genre like poetry or academic writing.

That spaces were created for specific narratives and identities was awe-inspiring. However, when I glanced at the list of people we were to meet, I realised that there was no Adivasi name, no Adivasi presence on it. That invisibility and erasure bothered me. Were we not important enough to be included as usual or were we non-existent in the publishing panorama?

Non-existent we were not; despite a shorter writing tradition, which really began with the arrival of the Scandinavian Missionaries, who in the early 1800s, published our tales from dictation of oral narratives. But significantly, we were still the sources and not the authors. For the Santhals in particular, the first published author was Majhi Ramdas Tudu, whose Kherwal Bongsho Dharam Puthi—the religious book of the Kherwals, a term for Munda-speaking people—was published in Calcutta in 1894 in the Eastern Brahmi script (Bangla).

Governance or citizenship doesn’t come from a document, a statute, or a law; governance is about relationships … This is not the India our ancestors sacrificed for or hoped for us, and this is not the India we want for our descendants.

We continue to write, in our native and adopted regional languages, mostly self-published, and yet our work wasn’t deemed significant enough to be part of this curriculum. That did it for me. I wanted the Adivasi voice to be counted, and knew I had to do something about it, without necessarily knowing exactly how. It was not a eureka moment, but instead a tipping point.

The adivaani idea was thus born out of the audacity to say enough is enough—to not being represented, to others speaking for us, to being labelled as unintelligent and non-thinking peoples, to being denied a place in history and literature, and to the Adivasi voice being silenced and suppressed.

I leaped into new terrain and tried to make sense of the vacuum I was working in, burdened by not knowing how to proceed. This wasn’t just about a straightforward agenda of representation, of visibility and deliberate, calculative measures to be seen and heard, but about what form this representation would take—it was about agency.

I quickly realised that the reason we were not being paid attention to by the publishing and literary world was because we weren’t publishing in English, but if that’s what it took to be included, respected, or even regarded, then we would do it, whether we knew the language well or not.

As indigenous peoples, we are living documents ourselves, so as a publisher, I was and continue to be confronted by the dilemma of transmitting, translating, and reproducing what’s organic and breathing into a form that in many ways is limiting. We are of an oral tradition and our knowledge systems are kept alive through singers, storytellers, and families, who in their oration preserve and recreate their community’s idea of itself. How do you then project and market such insight, experience, memory, and traditions, the tangible representations of which are books, audio or video files, a piece of fabric, food, photographs, sculpture, or painting.

As a publisher, while I need not explain what I do or what kind of material I produce to my indigenous community, I am called on to do so by dominant groups and audiences. To these majorities, the tribal narratives I produce are steeped in mysticism, wonder, and are often relegated to being of a lower cerebral order. That I can publish scholarly works doesn’t surprise these literate populations as much as the fact that indigenous peoples can produce intellectual material or any writing, for that matter.

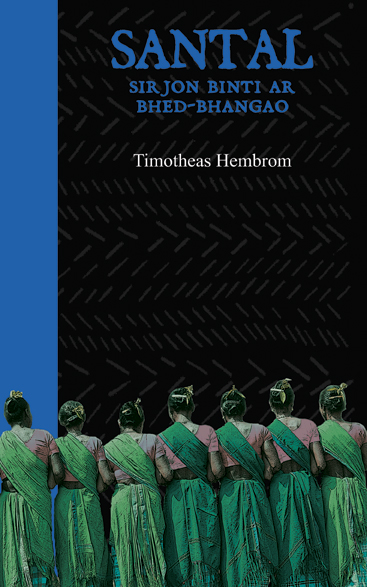

Another challenge for adivaani has been fighting the stereotypes and prejudice that have come to define Adivasi being for the public. Our first book, Santal Sirion Binti ar Bhed Bhangao, was in the Roman Santhali script, and was about the history of the Santhals as a people and entity. The base of the book’s cover is black. The printers we took the book to strongly recommended we change the black to a cheery yellow or a bright maroon as “black is too sophisticated a colour for the very backward Santhals.” Once you are discovered or identified as Adivasi, most dominant people automatically assume power over you and think that they are entitled to tell you what is or isn’t “sophisticated,” and where you do and don’t belong. How did a colour become earmarked only for one people? We stuck to black.

The distributors of an online book portal once refused to sign us on, citing that “Adivasi books are not good” without even looking at our work. The stigmatisation of Adivasi peoples and their knowledge systems is so deeply entrenched that any creative output or scholarship is looked at as an exception, a one-time, lucky spark of brilliance rather than a norm.

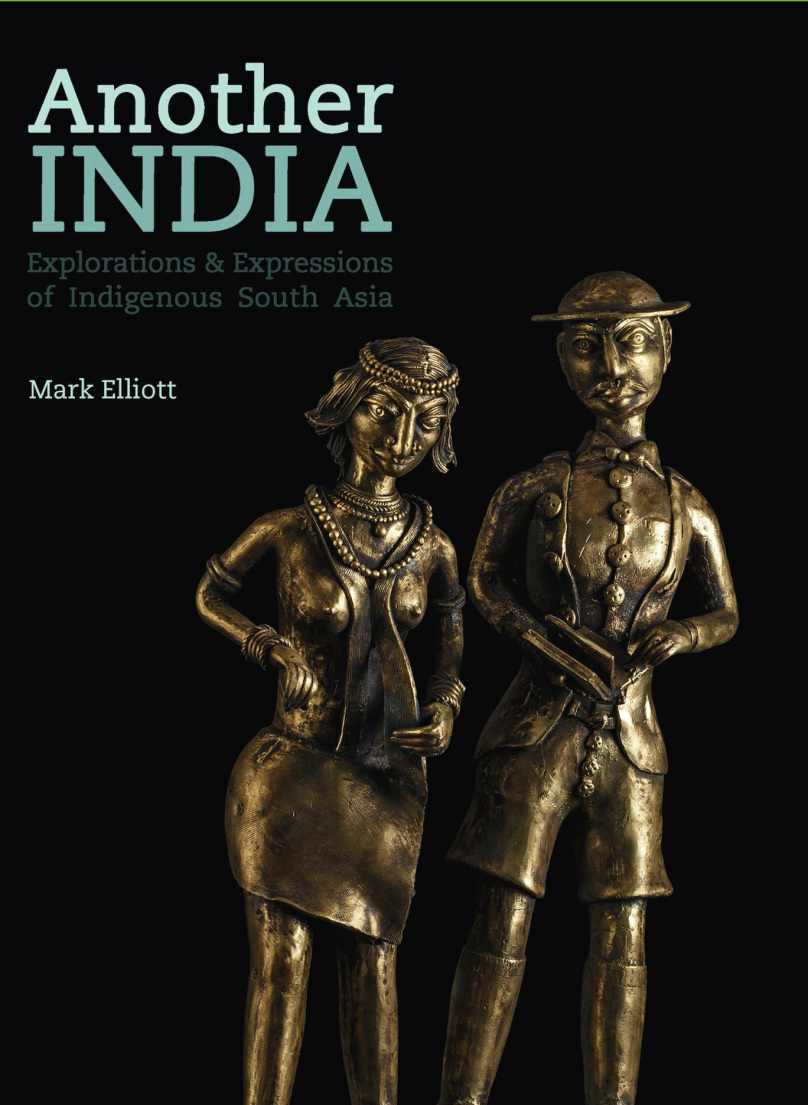

To the world at large, Adivasi literature is typically synonymous with folklore. My concerns are not with the one-dimensional understanding or interpretation of the Adivasi literary landscape. My concerns arise from the then-derived hypothesis that advanced societies have produced culture, while Adivasis have produced folklore, which is considered a lower form of culture because it is mythical. Adivasis are thus denied being a people of culture and are refused attribution of contributing to Indian artistic heritage and culture. In that one premise, the importance and urgency of producing Adivasi knowledge and material surfaces.

News of publishers being asked to pulp books that offend religious and other sentiments as a legal recourse only shows that laws can curb freedom of expression and literature and ultimately alter the pure form of any culture. In 2014, Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternative History was embroiled in litigation, with Penguin India withdrawing the book from the market and agreeing to destroy all existing copies within six months. In the same year Perumal Murugan’s Madhorubagan (One Part Woman) faced a similar fate and copies of the book were withdrawn. Though the Madras High Court dismissed the case in a landmark judgement, we still don’t know how our works will be received and what compromises we’d have to make in the process of producing Adivasi literature.

The need to assert that tribal works are a source of human history, and are not archaic but contemporary, has now become my mission as an Adivasi cultural documentarian and publisher. How tribal narratives cope with such bullying, gagging, and distortion of our histories is a key question. This situation of supervision, regulation or surveillance of culture further accentuates the need for Adivasis to take up documentation themselves and reclaim and control its production.

How do I, as an Adivasi, feel rooted to India and being a citizen? The fact that India is multilingual and multicultural indicates that its identity assertion space is also multilingual and multicultural. Indian-ness is in finding individual articulation and expression in its plurality in terms of social, cultural, historical, political, and linguistic components.

Governance or citizenship doesn’t come from a document, a statute, or a law; governance is about relationships. No matter how much we’ve talked of or engaged in social and political change, amendments and interventions, very little has actually changed for us. This is not the India our ancestors sacrificed for or hoped for us, and this is not the India we want for our descendants.

For an Adivasi, with a history and present steeped in lived experiences of exclusion and injustice, we seek inclusion, equality, and acceptance of our distinctiveness as peoples and communities in this plurality. Adivasis not only share the experience and memory of marginalization, we share the burden of knowing that we continue to live invisible lives. Before we reclaim, we need to claim; before we reproduce we need to produce.

Every time an indigenous person speaks it is a claim, a reclaim, a production, and a reproduction of a knowledge system that is key to our collective survival—an evidence

of who we have been during our centurial travel through our territories. This is claiming our collective place as human beings and refusing to be forgotten. Our knowledge is thus a shared resource, a narrative of pieces of resistance that need to blossom in a collective resurgence.

Every time I go to a library or a book fair, I am overwhelmed by the number of books on the shelves, left wondering about who would read ours in the mountain of uncountable books and also reflecting on the paradox of how many of us can actually read ourselves. Reclaiming the production of indigenous knowledge is also an assertion of its right to exist. Whether we are read or not—we need to have our say, we need to nudge our way into shelves just to be. Silence is not our mother tongue.

■

Ruby Hembrom is the Founder and Director of adivaani.