Citizenship and Art

The notion of citizenship is most often associated with the rights and responsibilities of an individual in relation to the nation-state. Even though theorists/historians like Benedict Anderson, in his influential book, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983), sought to draw our attention to the imaginative dimensions of nationalism, nevertheless notions of citizenship continue to operate primarily with respect to juridical and political norms.

As artists from diverse backgrounds, our shared collaborative practice investigates the remainders across which norms of identification operate in various contemporary societies. We are also deeply committed to engagement with everyday material and sensory processes that continually recreate a world that is more encompassing than the limits of statist, national, and identitarian affiliations.

Growing up in Karachi during the ’60s and ’70s in a family with parents who had both migrated from India after the 1947 Partition of colonial India into the independent nation-states of India and Pakistan, I grew up with many recollections of a familial and social life that was intangible and distant to our life in Pakistan. And before my teenage years, in 1971 the Bangladeshi struggle for independence from Pakistan precipitated war between India and Pakistan. During the war, many bombs were dropped on Karachi— my school had also been bombed. Despite the effects of war all around us, after the war, the Pakistani government refused to formally acknowledge the loss of East Pakistan and did not recognise Bangladesh as an independent nation- state diplomatically until 1974—during these years of non-recognition, imported magazines and atlases would have the name “Bangladesh” crossed out in black ink by the government censors. For someone still in middle school, this was all very puzzling and unsettling.

Over the years, as I have sought to make sense of these experiences, I have come to realise the degree to which aspects of this experience resonate with others from South Asia and indeed from other postwar nation-states. The decolonisation process, which created new nation-states along Westphalian lines, also ended up shaping the lives and imaginations of their citizens and their subjects. In doing so, other affiliations that communities and societies had developed from premodern eras were denied. But my distrust of the closures of the nation-state was also shared in many ways by Americans I met after I arrived in the US to pursue higher education.

My artistic work over the last two decades has involved an ongoing collaboration with Elizabeth Dadi. Elizabeth grew up on the West Coast of the United States and studied in San Francisco during the ’80s, in an environment that had already been deeply transformed by political and social activism from the late ’60s onwards, and was characterised by profound skepticism regarding the imperialist role of the United States during the late Cold War. Elizabeth studied art at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), which at that time had a very supportive and open environment for critical thinking and for conceptual, new media, and performance art—its alumni included artists like Paul McCarthy, Jay DeFeo, and Stan Brakhage and its faculty included African- American painter Robert Colescott, who reworked motifs from historical paintings towards a parodic critique of race; the multicultural activist and Filipino-American artist Carlos Villa; and the experimental underground filmmaker George Kuchar. Her classmates also came from diverse international backgrounds, and many addressed social and political dilemmas in their work.

Our media-saturated environment creates paradoxical effects: it legitimates official closures through the selection and repetition of powerful narrative forms and affective sensory registers. But simultaneously, popular, counterpublic, and vernacular material and media cultures also persist and become amplified.

Both of us had thus arrived at a juncture where we understood that the art of the present needs to address these quandaries of the self in a divided world. Our collaborative practice for two decades can be placed at the intersection of conceptual art, pop art, and popular culture. The latter term denotes not only the art of mass culture in postindustrial societies, but also the rich materiality of urban street life in cities of the global South, and especially in South Asia, where one encounters bright plastic artifacts from various sources in dense juxtaposition, and where lights, decoration, and signage play a vital role in orienting one’s consciousness and in establishing a relation to the specificity of place. Our practice interrogates both the blindness of official narratives, and the spectacular immersions of popular cultures, by bringing conceptual rigour to a dialogue with the sense and affect of the popular. Two recent projects that we have undertaken underscore these concerns.

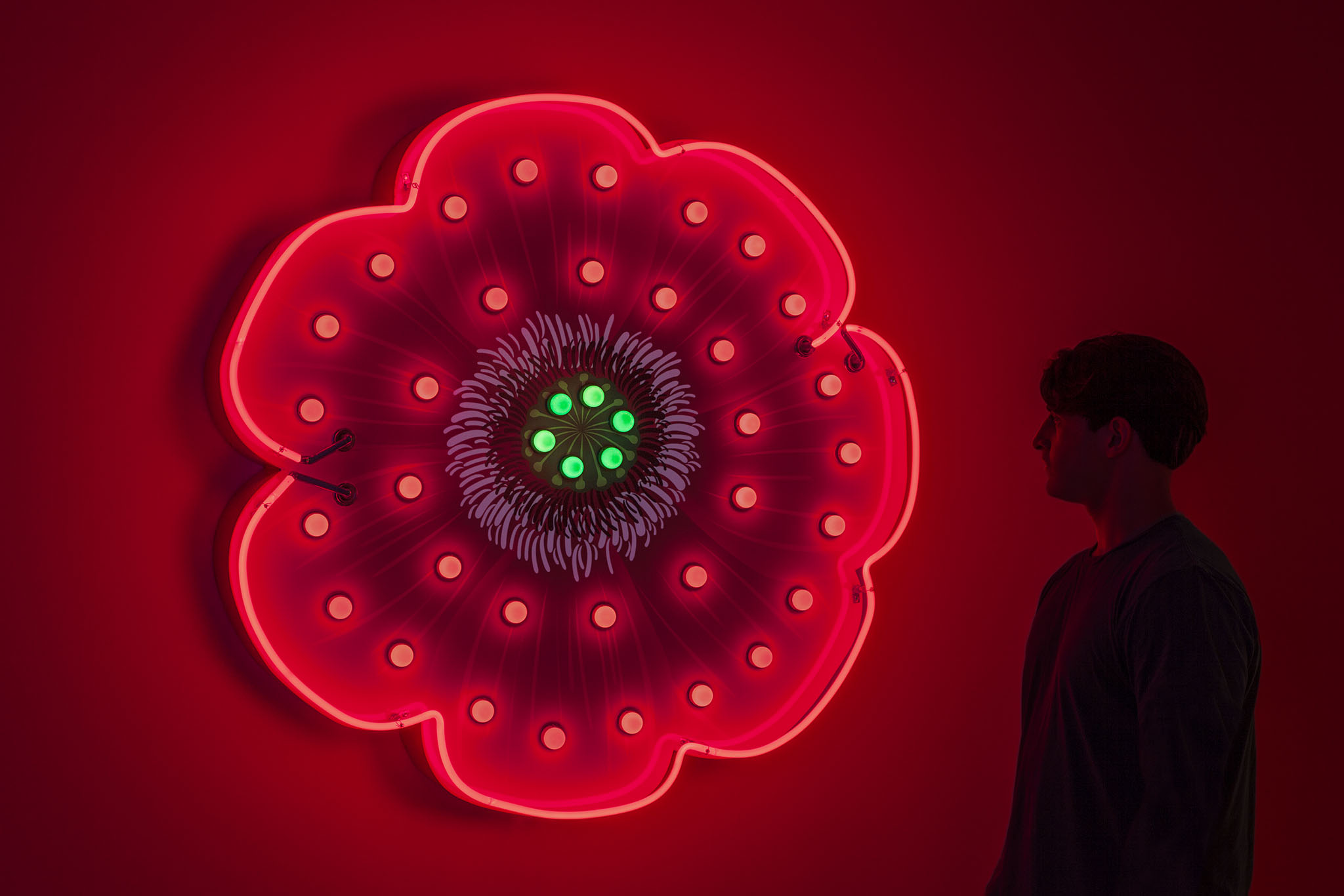

The Efflorescence (2013-onwards) series visualises the strange symbolic emblems of official imagination through a popular visual register of materiality. Benedict Anderson has argued that imagination plays a central role in how nationalism incorporates individuals in its projects, and the official emblems that countries celebrate are therefore not incidental to their claim upon us. Nation-states ascribe various forms of pageantry exclusive to themselves in order to express their singularity. Among other emblems, flowers have become specific national symbols, even though they grow over a wide geographic range. As markers of national identity, they are especially arbitrary, and can truly be characterised as “contested botanicals.”

The Efflorescence series is inspired by the strangeness of this attribution. The word denotes the blooming of a flower and the flowering of a culture or a civilization.

Other connotations include the positive sense of glowing and being lit, but the word also bears negative valences, such as the manifestation of a stain or discoloration. This doubled sense of the word provides an evocative title for this series, which focuses specifically on the national flowers of contested regions. Inspired by popular commercial signage and created as large neon and incandescent works in metal, the works jump scale in their materiality and dimensions. Their graphical form and their industrial artifice acknowledge the manner in which such delicate natural forms are institutionally deployed as fixed emblems to vindicate intangible claims of identity.

Efflorescence: Shaqa’iq an-numan

Efflorescence: Shaqa’iq an-numan

2013-2015, Installation at John Hartell Gallery, Cornell University (2015)

Neon, bulbs, aluminum, mixed media, Each 48 x 48 x 12 inch

The Efflorescence series constitutes a chapter in our continued investigation into how our consciousness is shaped in the era of mediatized biopower. Our media-saturated environment creates paradoxical effects: it legitimates official closures through the selection and repetition of powerful narrative forms and affective sensory registers. But simultaneously, popular, counterpublic, and vernacular material and media cultures also persist and become amplified.

Roz o shab is a site-specific work created for the Lahore Biennale in 2018. The work was in the Summer Palace, located under the platform of the Mughal-era Lahore Fort. In its undulating form and using the medium of neon, the work situates itself in a complex relation between the Mughal era and the present. It refuses nostalgia by deploying a form and medium that markedly differs from the materiality, symmetry and order of Mughal architecture (but it does reference fluid motifs of the miniature, and of serpents in traditional games like snakes and ladders.) Roz o shab also pays homage to urban aesthetics, in Pakistan and Mumbai and Dhaka, and in places like Hong Kong and Las Vegas that have large-scale neon signage.

The large hall in which the work was installed has a wall 40-feet thick, with two narrow tunnel-like windows that end in screens facing the outside. Even during the day, the hall

is quite dark, evoking a sense being suspended in time and space. One hears and senses the outside world, but at a remove. The Summer Palace also has a complex network of water channels. And the rear section of the Summer Palace has a maze-like layout with a hidden bedroom, and narrow and dark stairs leading to small hidden chambers. It is like

a bhool bhulaiyan, a maze that one finds in Mughal and Oudh architecture.

Other suggestive references for the work’s conception are that the Ravi River had earlier flowed adjacent to the Fort, and that the poet Muhammad Iqbal is buried nearby. Specifically, the work situates itself with respect to Iqbal’s poem Masjid-e Qurtaba, which he had written in the 1930s after a visit to the famous building in Spain, which had

not been used as a mosque for several centuries since the Reconquista by the Spanish. The poem is a philosophical and existential reflection on how we might relate to a past whose flow and continuity has shaped our present, but which has also been severed from us.

![]() Roz o Shab

Roz o Shab

2018, Site-specific installation in Summer Palace, Lahore Fort, Lahore Biennale 01,

Neon, mixed media, 25 x 16 ft

The Mughal era was undoubtedly marked by great cultural achievement. But it was a hierarchical society, rather than being an egalitarian one based on citizenship. And it was pre-industrial. We have no wish to romanticize that era. But the question of how one might meaningfully engage with one’s past cannot also be evaded. Our project aims to acknowledge the site, its history, its architectural balance and symmetry, and the strange sensorial effects the space and the windows evoke. We have attempted to do so by inhabiting three tensions: between the centuries-old past and the evanescent present; between light and dark or night and day; and between Mughal architectural decorum and a playful undulating form that recalls contemporary children’s puzzles and rivers and serpents in Mughal painting.

Part of the work consists of two lines of text facing each other as if in dialogue. They are drawn from Iqbal’s poem Masjid-e Qurtaba. The opening stanza is:

silsila-e-roz-o-shab naqsh-gar-e-hadsat

[The succession of day and night is the architect of events]

The word naqsh-gar (architect) has the sense of making

a design or inscription (naqsh), which are also found as ornamental patterns on the walls of the Summer Palace. The emblem is abstract, and suggestive of geometric ornament but also a stylised flower or lotus at which the neon “river” of time arrives.

The second stanza reads:

silsila-e-roz-o-shab tar-e-harir-e-do-rang

[The succession of day and night is a two tone silken twine]

The two verses provide spatial and philosophical bookends for the undulating form that has two colors –blue, and red. The texts written in neon are based on Iqbal’s own handwritten manuscript. The casual way the text is written also suggests levity when reading these otherwise weighty philosophical proclamations.

However, when works of art become public, their meaning cannot be restricted only to the intentionality of the artist(s). Works of art have relevance to others precisely because they are multivalent and generative of new significations, for publics beyond the specific circumstances and concerns of the artist. For example, some observers found resonances in our installation with the ongoing brutal transformations in Lahore’s public infrastructure, with its flyovers and elevated roads. Others noted that the work suggested a “meandering starburst that had lost its sense of direction and place,” that was nevertheless “aspirational.”

■

Iftikhar Dadi is an Associate Professor at Cornell University in the Department of History of Art.