Feminist Posters From the Zubaan Archives

On the 21st of January, 2017, the United States of America witnessed its largest ever single-day protest in the Women’s March, with over four million protestors within the country, and over a million participating in simultaneous marches around the world. The publication Wired declared: “the women’s march defines protest in the Facebook age.”

The centrality of social media in helping garner support from all over the world and share news and images from the various marches across numerous platforms underlined the ubiquitous demands for women’s rights and the urgency to address them.

But what followed the march was also interesting. Scholars, students, volunteers, and curators from leading cultural institutions such as the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., began to collect posters and signage that had been left behind in the wake of the protests, asking demonstrators to donate their protest materials. One of these posters stated: “Too many demands for one poster.”

For a movement as complex and layered as the women’s movement, how does a poster communicate its numerous aspects? As a protest for the Facebook Age in a time of powerful digital media, how does a medium like the poster compare to the fast-paced and ephemeral nature of social media?

For a country like India, which has a brief history of formal design since the sixties, design in the form of posters can claim to have existed long before that, since colonial rule, due to their extensive use in the field of advertising. Their low artistic merit and cheap printing likely made it difficult for them to be preserved and thus become a part of larger national archives.

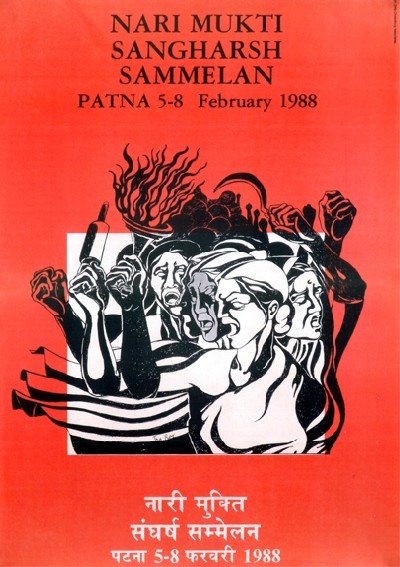

With the primary function to announce, inform, or persuade, protest posters have relied heavily on the use of powerful and memorable imagery to immediately perform these functions visually, before demanding a more cerebral engagement. Also stylistically, the vernacular nature of it meant they were deriving from whichever environment they were to be used in.

Thus, this primacy given to image—either in the form of pictures or of text-as-image—makes posters a particularly resourceful medium to understand the visual culture of a given time.

In a similar initiative in 2006, predating the Women’s March, Zubaan, an independent publishing house based in New Delhi started Poster Women, an undertaking to document and archive posters that were printed as part of women’s movements in India from the 1970s to the 2000s. The idea was “a visual mapping … to ask what the history of the movement would look like through its posters and the visual images it had used.”

Using only the images produced by the women’s movement available through these posters, the attempt of the archive was to investigate: who is the woman that the movement represents, and what is she fighting for?

Over 1,500 posters in the archive have been divided into various categories, from religion to environmental protection, marking a range of issues that have been taken up by the movement over different temporalities and geographies. Posters from some autonomous, spontaneous, and isolated movements like the anti- alcohol movements in Assam, anti-arrack protests in the Andhra Pradesh, and protests against female foeticide in various parts of the country, are the only forms of visual documentation available about these protests. But the archive also acknowledges the under-representation of certain issues, such as campaigns against widow immolation, and regions, like Kashmir or states in South India, in their collection.

Geography presents a direct link between the visuals that emerge with imagery and style influenced by local and regional art, with posters using forms from the Madhubani (Bihar), or Gond (Madhya Pradesh) traditions, for example. The local communities, who were likely the initial artists, thus appear to have had an active, involvement with the conversation around the movement in these regions.

Other posters from organisations such as the Dalit Dastan Virodhi Andolan in Punjab, Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), Ahmedabad, and Jagori, Delhi, acknowledge the efforts at the grassroots level, countering the notion that Indian feminism has for long refused to consider the lived experiences of class, caste, and religion, excluding these from the larger feminist discourse.

It is difficult to define a generalised aesthetic for the visuals from these posters, though there are similarities that transcend regional diversity; the recurrence of certain motifs such as a mother goddess, or the more traditional image of a sari-clad, long-haired, mostly-Hindu woman, result in the creation of visuals which become popular symbols of the movement. Initially, this probably emerged as a result of attempts to bring acceptability and relatability to the women’s discussions in certain regions. Whether arrived at wittingly or unwittingly, as the women’s movement progresses, taking within its fold various identities and related issues, it becomes essential to address: how do we reimagine this image of the “common” Indian woman?

Popular imagery such as the sickle, which originated as a part of largely peasant and left movements, also creeps into the archive. In this manner, the women’s movement becomes a corollary to, or extension of, issues of class and rights taken up by earlier protest movements. As a form of collective protest, then, what are the range of issues that the feminist movement fights for and will fight for in the future? And will this participation in collective social resistance and an engagement with intersectional feminism demand the creation of a new visual vocabulary?

India finds itself in a perilous political moment. With voices standing against majoritarianism and justice being silenced at alarming levels, there is a growing threat to the freedom of speech and protest, witnessed most recently with the arrest of five human-rights activists across the country for spurious links to Maoist conspiracies. Acknowledging that any form of oppression is inherently a violation of our rights, makes this a collective struggle for freedom.

To return to the questions of who and what the women’s movement in India represents, while the posters present the historical context of the origins of certain imagery, and in some cases are the only visual documentation of key issues within the movement, as the feminist discourse progresses, initial questions need to be rephrased—who all does the women’s movement represent today and what all are they fighting for?

At a 2013 exhibition called In Order to Join, originally shown at the Museum Abteiberg, curators Swapnaa Tamhane and Susanne Titz presented the work of 14 women artists who tackled concepts of activism, protest, and philosophy, all while seeking new definitions of feminism. The exhibition featured Rummana Husain, whose works reflect her dual subjugations of being a woman as well as a Muslim during a time the country was headed by a pro-Hindutva government. One of Hussain’s posters in the Zubaan archive features an image from her series Home / Nation (1996), documenting residues of violence in Ayodhya after the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992, a highly contentious moment in India’s communal history. “In Defence of Our Secular Tradition,” the poster expresses discontentment with religious nationalism locating it in the sphere of feminist concerns.

In a moment when feminism is heading towards a more intersectional future, where discussions are acknowledging overlapping social identities, our images need to keep with this changing dialogue. How advancements in media and the power of social media influence this new visual vocabulary remains to be seen. Will the poster be able to evolve to accommodate the many demands?

■

Sukanya Baskar is currently a Curatorial Studies student at CCS Bard, New York.

Left: C.F.John, Mercy Kappen Visthar, Karnataka, 1994 Right: Provenance unknown Bihar, 1988