Interview: Dalit Image-Histories of Nepal

The chances of “truth” surviving the onslaught of power are very slim indeed; it is always in danger of being maneuvered out of the world not only for a time but, potentially, forever. Facts and events are infinitely more fragile things than axioms, discoveries, theories—even the most wildly speculative ones— produced by the human mind; they occur in the field of the ever-changing affairs of men, in whose flux there is nothing more permanent than the admittedly relative permanence of the human mind’s structure. Once they are lost, no rational effort will ever bring them back.

This warning by Hannah Arendt, pioneering German-born American philosopher and political theorist in her 1967 essay, “Truth and Politics” speaks to the redactions of histories, the vagaries of time that distances us from events, and the truth claims that must be made when faced with autocratic regimes—truths that must be recorded or relayed effectively and vigilantly by those who confront or witness atrocity. Power—to resist, desist and challenge then lies with the people, but the lack of visibility often undercuts our ability to assert counter-arguments. And when ideas and facts become mottled and abstracted through truncated versions and hearsay, we must also ask whether visibility itself can become a potential tool or cause for oppression too?

With reference to the Dalit community in Nepal, Diwas Raja KC, Curator of Dalit: A Quest for Dignity in 2016 and the author of the book by the same title notes: “Dalits make complex decisions daily around their own visibility. Where to be seen? How to be seen? When could “being seen” publicly assist their freedom and when could it invite more danger and humiliation? These concerns around visibility no doubt extend to the acts of photographing and being photographed as well.”

By documenting atrocities upon the community, which perpetrators frequently do as they videograph and share these clips as acts of retribution, punishment or sheer vindictiveness, Diwas suggests that in certain situations, giving visibility does not intrinsically bolster their situation or oblige their cause. This requires essential contextual, if not an historical reading in order to forge an arc or trajectory around their “experience.” Any act performed to add or remove from the thesaurus of images surrounding such events must make us question the ethics of viewing itself—in order to see the layered or ingrained structures of discrimination and identity politics within the images (or histories). How will we otherwise be attentive to the “complexities of their lives and ambitions,” or their exclusion from narratives of the country’s past, and absence from many public spaces?

In an extraordinary effort to reclaim such a space, the Nepal Picture Library (NPL) has been generating an archive on Dalit society and experience, bearing in mind that the efficacy

of records and documents are also contingent on power relations. Here, Diwas probes some of the decisions which defined his curatorial delivery of the exhibition drawn from the NPL archive and the challenges of representation when re-telling history in a decidedly inclusive manner.

How and why was the exhibition conceived?

The project came about because of the growing ambition of Nepal Picture Library to become a fully inclusive visual archive. While Nepal Picture Library had so far been working with private albums and collections in order to reflect the multicultural reality of the Nepali people, we felt that we needed to do more to become the kind of repository of

visual records that could properly enable silenced, obscured and fragmented parts of Nepali history. We are increasingly designing our archive to be an intervention in the image

and idea of what counts as the “public” in Nepal. So, we are working with a heightened awareness about how mainstream and alternative forms of publics—or simply publics and counterpublics—have formed themselves and have jostled for space and inclusion.

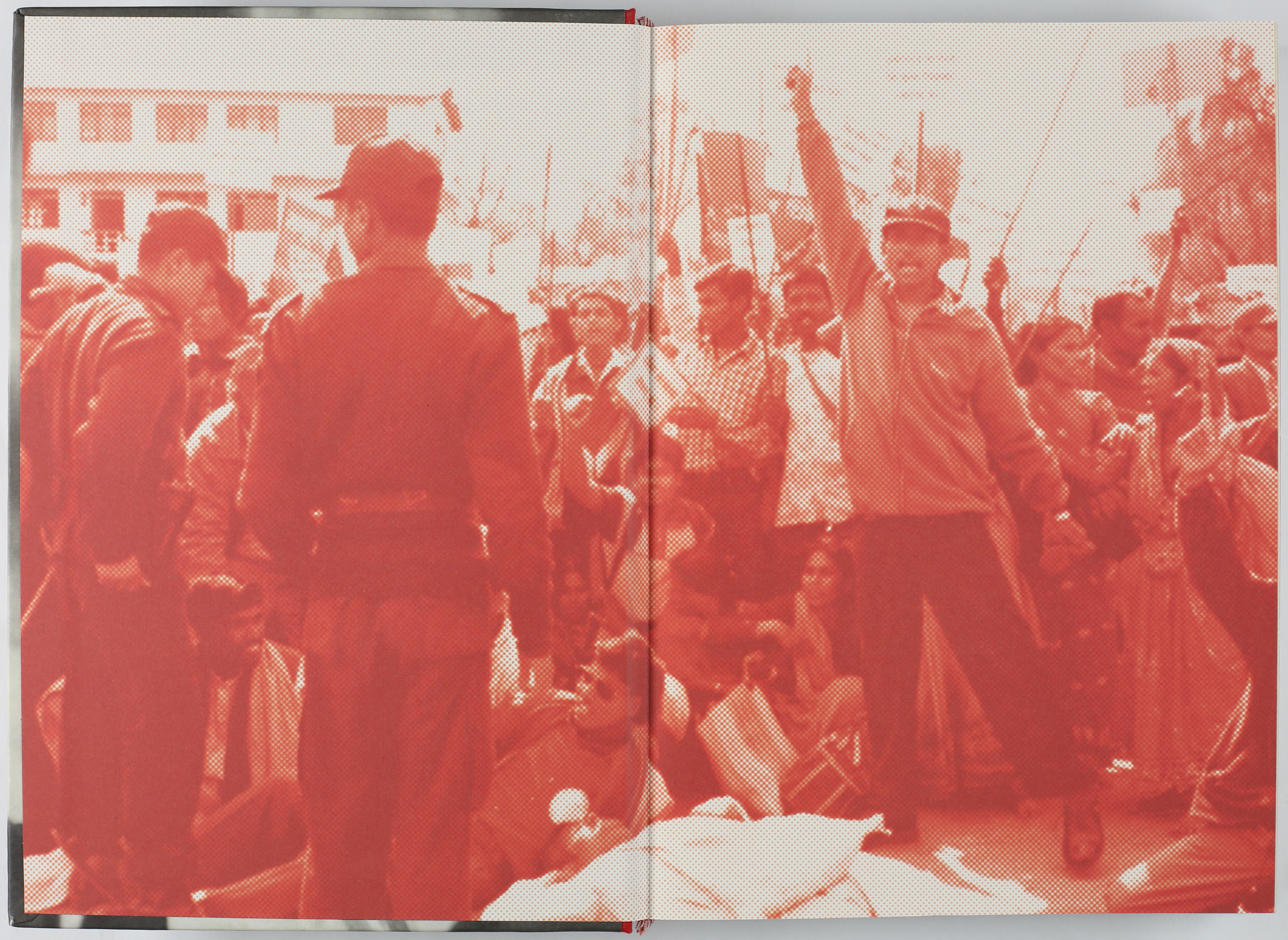

The exhibition was essentially an extension of our archive- building efforts, part of our argument that archives shouldn’t exist as static institutions but become active means for people to deepen their connections with the past. In that sense, the exhibition was also meant as an intervention in public memory. The selections and curation highlighted the experience of witnessing a certain kind of history of the caste regime in Nepal. In some ways, more than any specific insight about what Dalit life is like in Nepal, it was the burden of simultaneously knowing and not knowing our own history that we wanted to convey through the exhibition. And it was our wager that such a reflection on history also mattered deeply to the Dalit movement.

Records too can be tools of oppression and display techniques of power … whose voice can and cannot be used when representing the experiences of a community?

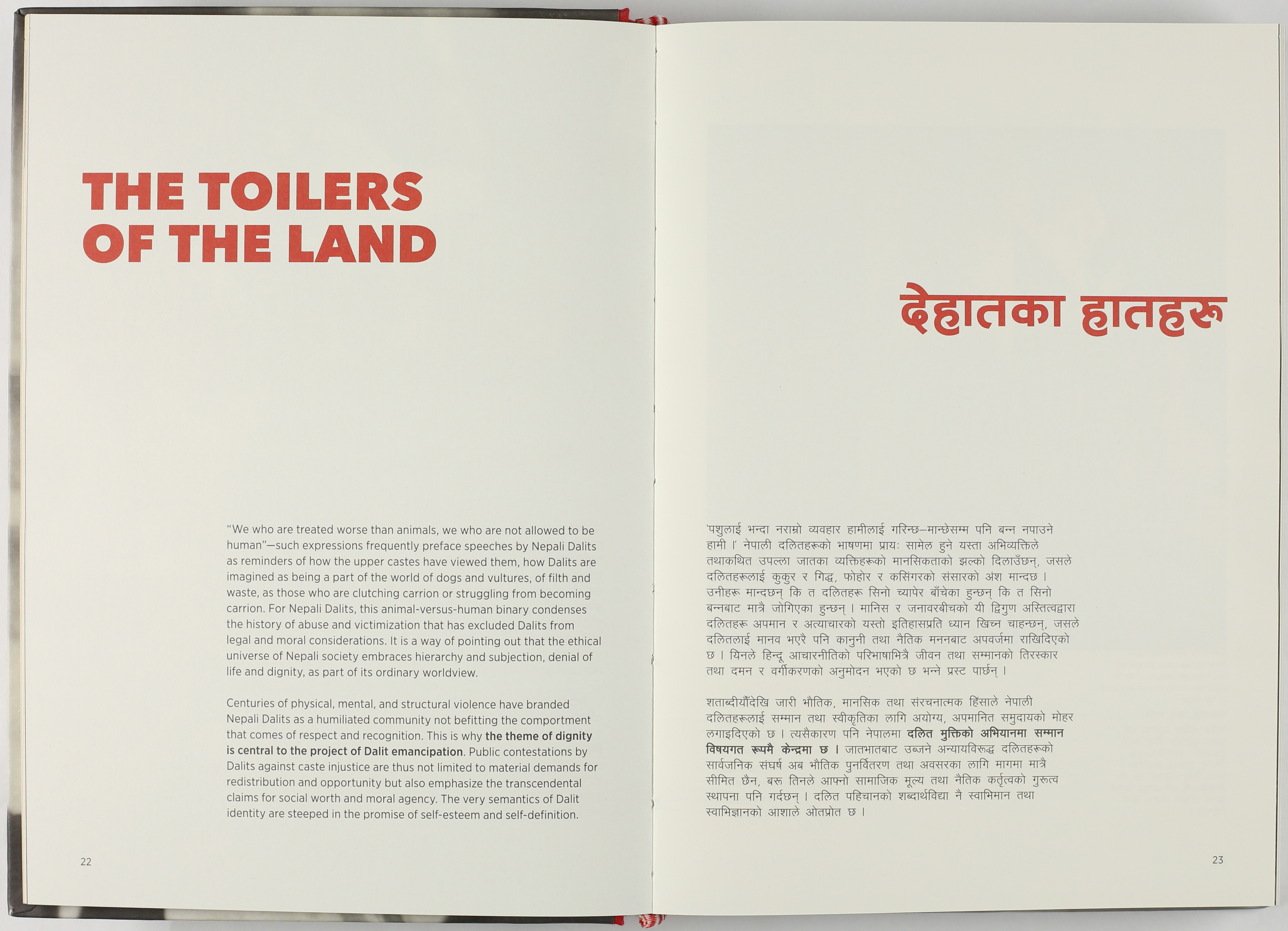

The Dalit community of Nepal is unsurprisingly one of its most neglected and vulnerable populations. And one that could arrive on the political stage only after violent thrusts towards change and revolution in the country. The questions of how to represent the community (both aesthetically and more importantly, politically), who gets to represent the community, whose particular agendas count as pan-Dalit issues, and so on have been fraught, not least because of how poor the conventions of Dalit representation have been. Although at the sociological level it might be possible to identify the specificities of Nepali Dalits, given the distinct patterns of development, modernity, urbanisation, and political formations in the region, the community is, in fact, an extremely diverse one and the unity of Dalit identity has taken serious groundwork.

All of this contributed to the exhibition being uniquely difficult to design. For our part, we felt we needed to structure the show to speak to the widest possible audience but also make sure that it obstructed any facile comprehension of Dalit circumstances in Nepal. The exhibition had to be introductory at one level but also persuade viewers to constantly question and revise their own knowledge and preconceptions. I think a lot of the viewers had come to the exhibition expecting to encounter only deprivation and depredation – victimhood and powerlessness. But we were also pleased to hear from many that they felt the exhibition was providing a more nuanced picture – that it was presenting Dalit experience not as a self-contained lifeworld of a community but as having deep consequences for the entire economic, cultural, and political history of Nepal.

“Records too can be tools of oppression and display techniques of power.” Taking this as a premise, how did you maneuver the challenges of gathering material from archives while curating content for the exhibition?

There weren’t as such any existing archives about Dalits for us to gather materials from. It was because we wanted to create an archive in the first place, believing that Nepal Picture Library had such a responsibility, that we commenced the project. All the wisdom about creatively working with erasures, elisions, and ruptures in the archive which subaltern historians have taught us, fully applied here.

We obviously started by turning to Dalit-identified organisations to see what kinds of materials we could find there. Early on, we had formed close working relationships with Samata Foundation and Jagaran Media Center in Kathmandu, and both organisations are diligent about keeping news clippings. Jagaran also had a trove of photographs from its events, projects, and record-finding missions that were useful for our project. Jagaran, as well as the network of Dalit journalists we came in touch with, take record-keeping of atrocities against Dalits as their prime function. Especially, one finds that the indexical and documentary quality of photographs has come to be of major importance for Dalit activists and journalists as so much “evidencing” is required around the violence and social injustice faced by them. But the type of material that comes from the exigencies of recording and reporting also invite a fair dose of cynicism about what records can actually do towards guaranteeing justice. For justice continues to be elusive and one can easily be overwhelmed by what actually goes unrecorded and unreported. It is hard to ignore the fact that the efficacy of records and documents are also contingent on power relations.

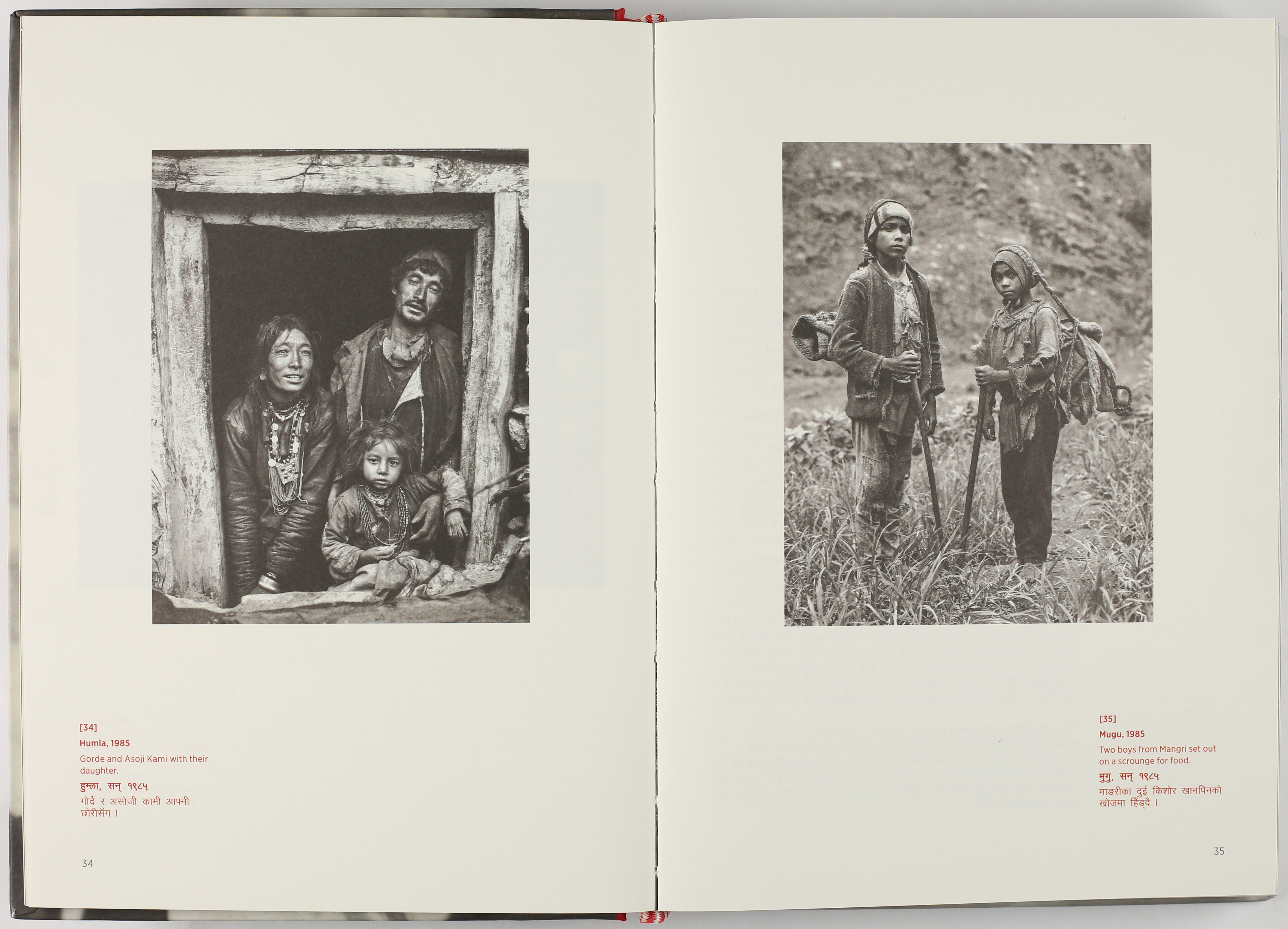

Then there were also temporal silences that we had to struggle with, as in the problem of finding materials from the period before these Dalit organisations and journalists were active. With the kind of confined public sphere that existed in Nepal, the period before the democratic uprising of 1990 and sometimes even the 1990s can be difficult to trace, especially in terms of photographic records. For our exhibition, we luckily found a few personal collections belonging to activists and academics that could reveal significant aspects of Dalit life during the Panchayat Period (1960-1990). We were also tremendously fortunate to have access to an amazing archive of photographs taken by Peace Corps Volunteers created by American activist Doug Hall, which we mined thoroughly to identify Dalit subjects. This did mean that we had to be even more mindful of the representational aspect of the exhibition, but I think overall we did manage to bring attention to the outlooks and perspectives of Dalits as a community in particular.

Whose voice can and cannot be used when representing the experiences of a community? How does agency return to the subject in a project like this? What were some of the other decisions taken (for example the non-capitalisation of the word dalit) in order to present the narrative in a new light?

The bulk of images in the exhibition were not taken by Dalits, yet the purpose of the entire exhibition was to extendedly explore the elements and textures of Dalit identity. We have not been oblivious to the irony of the ventriloquism required to perform such a task. We were not so naïve as to think that we could somehow channel and overlay our speeches with those of the Dalits. But somewhere the project did require that we do not think of “voicing” and “agency” in a direct and straightforward manner.

Perhaps allegorizing agency through the “voice” for a photo exhibition is counterintuitive to begin with. Insofar as the question was about Dalit agency, we were more caught up with the problems of vision and visuality. Our argument was that it was indeed possible to train ourselves to “see” what Dalits do with the dilemmas of their own visibility.

Non-Dalit photographers may very well photograph using an outsider gaze and the overwhelmingly non-Dalit viewers who frequent exhibition spaces may also be used to looking at Dalit iconography from their own perspectives. But photographs also work by referring to a world that is much wider than what’s captured within the frames. We meant to draw attention to the fact that Dalits are also “looking” and acting with the knowledge of the particularities of vision in a caste-based society. So, when we work with a more ocular understanding of agency than a sonic one, our questions about it need to maneuver accordingly.

In addition, I was also interested in unearthing new theories about ways of looking at the situation of Dalit vision, taking us into a non-representational territory. If so, questions about modes of embodying, encountering, and inhabiting the social world would need to take precedence. The other thing we did to address the issue of agency was to adopt the aesthetic strategies of Dalit protest – that of transfiguring anguish and dispossession into a visage of dignity and inalienability. This was crucial in order to ensure that the exhibition highlighted the politics of Dalit self-affirmation and presence. Dignity is the term that brings together all the material and symbolic constituents of the Dalit movement. And it affords us the prospect of accessing Dalit experience in the context where it may be difficult to speak of the same through identity.

With regards to the capitalisation of “Dalit” versus “dalit,” we did give it some thought but perhaps not enough. Both are conventional, and perhaps in our vernacular languages, such a debate makes little sense. We settled with lowercase for the exhibition because we understood the word as a proper noun designating a group or community as well as a term signifying a worldview and a political possibility. The issue of capitalisation was raised by one of the reviewers of the exhibition, but the critique came more from a place of policing English usage rather than from a consideration of choices people make with any language. Subsequent to the exhibition, however, we have switched to using upper case, because we realised that similar stylistic contestations have also occurred around terms like “Black” and “Indigenous” and respective communities have increasingly pushed for capitalisation as another effort at recognition.

What are some of your forthcoming activities around the archive?

The archive has continued to grow since the exhibition and some of that will be visible in the publication Dalit: A Quest for Dignity (now published). One effect the exhibition has had for sure is the realisation of the importance of good documentation practices and that generates the possibility for creating multiple archives that can work in collaboration.

We are looking forward to taking the content far and wide, because the material does have the capacity to speak to broader issues of contemporary politics, history, archival practices as well as visual culture.

The Dalit project has also triggered a new sensibility towards visual history at Nepal Picture Library and we have started to apply this sensibility to other areas of Nepali social

and cultural history. One outcome is the present Feminist Memory Project we started this year whose scale and scope is already extraordinary. In the coming months, we will also be preparing an exhibition of this material, which we are certain can further the conversations we have already begun with our Dalit work.

■

Diwas Raja KC is a researcher, writer, and curator based in Kathmandu. He was last at the University of Michigan pursuing academic training in South Asian history and anthropology. His work has focused on various social movements in South Asia, especially examining issues of gender, sexuality, and labour. He is also a part-time documentary film editor and a commentator on visual culture.