Interview: Reconstructing Photography and Otherness

How are questions around citizenship and identity tackled through photography by Autograph ABP?

Historically, the visual arts and photography have been a vital component in the execution of Western, supremacist, and colonial policies, especially in relation to the extreme exploitative and aggressive imperial desires that endorsed systems such as slavery and the extinction of indigenous peoples. I would argue that it is therefore logical, or indeed necessary, to engage artistic production not just in geographical or racial terms, but in terms that fundamentally seek to investigate how power works and who is ultimately speaking for whom. At Autograph ABP, it’s been a core institutional driver to disrupt the canon of photography and build a more democratic global understanding of the role photography plays across identity formation in different times, geographical spaces, and within different communities.

Can you highlight some of the personal history projects which have a political mandate? Are there South-Asia-specific projects that you can speak to in particular?

In early 2007, I got an email from the photographer Sunil Gupta who had just recently returned to India. The photographs he sent represented a marked shift in his practice and came to represent a newfound confidence in his returning to India and engaging directly in the politics of queer rights there. His series, The New Pre-Raphaelites, aimed to reinterpret well-known references to Western art history that had gained a degree of international recognition and cultural familiarity. The work strategically referenced the Pre-Raphaelite group of painters in England, which formed to contest the stifling norms of their world, especially assumptions around sexuality and gender. Gupta chose to adapt their focus on the sensual arrangement of the body and re-work the tradition to re-create and radically visualise a modern Indian queer identity. The nature of the project was transgressive, radical, and quintessentially political—it visually campaigned for change and the acknowledgement of a section of society rendered invisible by the state. His practice illustrates fully what Ariella Azoulay has called the “civil contract of photography,” a practice that is always directed towards the ethical and political conjunctures of photography.

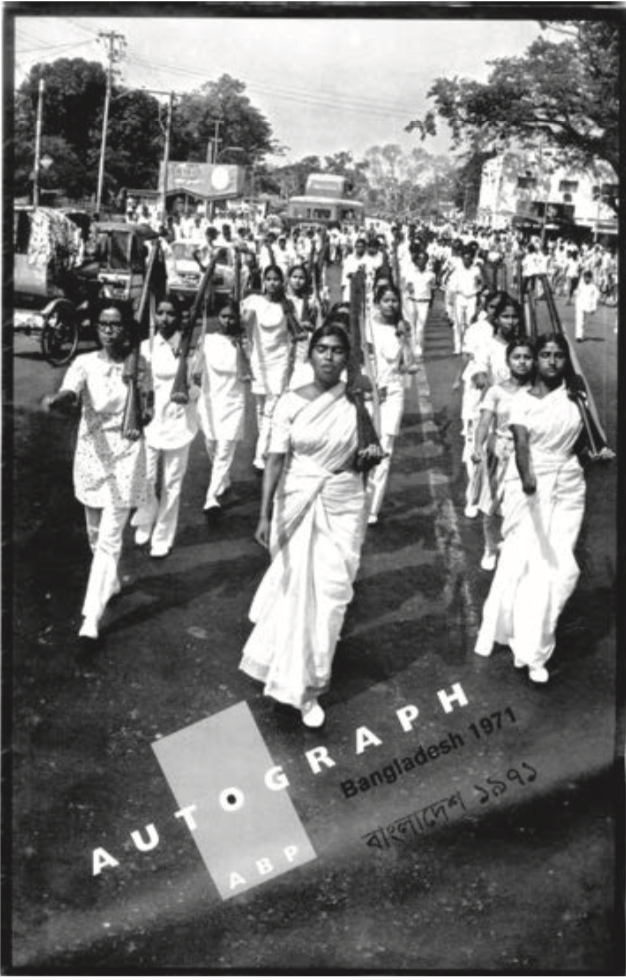

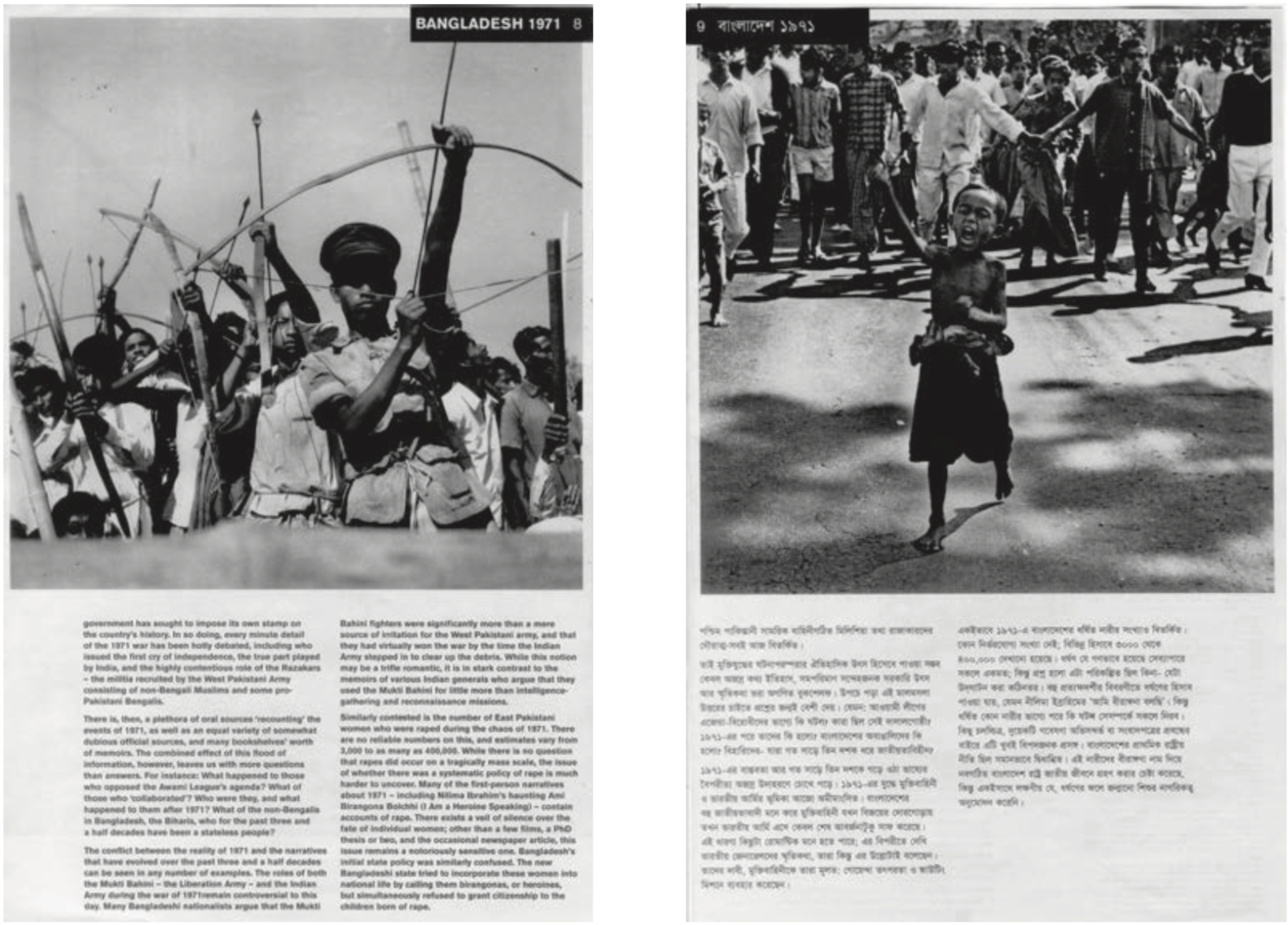

In 2008, I co-curated a major documentary photographic exhibition of primarily Bangladeshi photographers that focused on the independence struggle in 1971. The exhibition was produced in partnership with Shahidul Alam, director of Drik, and a media activist and journalist from Bangladesh. This was to be the first comprehensive review in the UK of one of the most important conflicts in modern history. 1971 was a year of national and international crisis in South Asia. It is recognised that over a million people died in 266 days during the struggle for an independent Bangladesh, whose history is implicitly tied to the partition of India in 1947, therefore inextricably linking the tragic events of that year to Britain’s colonial past. For Bangladesh, ravaged by the war and subsequent political turmoil, it has been a difficult task to reconstruct its own history. It is only during the last few years that this important Bangladeshi photographic history has begun to emerge; it’s a history that is part of an important Cold-War narrative that often gets neglected. The exhibition was a direct invitation to local Bangladeshi communities to discuss their young nation’s past and also celebrate its photographic and film histories.

Eurocentric photography is haunted by its own colonial psyche, and reading the history of European photography in the present tells us much more about the colonising eye than it does about the myriad foreign, othered subjects it focused on.

The old history of photography is now read as a fragmented and broken body, consumed by the fact that it is full of missing chapters, absent stories, and neglected or overlooked archives. It is therefore pressing that these lost photographic moments, particularly those produced by the Other, marginalised or historically colonised peoples are brought out of the archive and into the world. These images will only help identify and close the historical cultural gaps that imperial photographic regimes have imposed across our visual understanding of the world.

It is only since the celebrated 1994 Bamako photography festival that photography’s Other histories began to enter Europe’s cultural institutions in any meaningful way. The celebrated Malian studio photographers Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, have now entered photography’s great halls of fame. The events at Bamako 1994 mark the beginning of a decolonial history, one that is diasporic and multifaceted, surfacing out of photography. What’s compelling about these Malian and Other studio photographic practices such as those of Suresh Punjabi—who founded Studio Suhag in Nagda, a small town in Madhya Pradesh—is that the images produced there reside both within and outside of European photographic epistemic systems. They require local knowledge to interpret their meanings fully; as archives, they reflect the outcomes of global human exchanges and encounters.

Critically then, for us to fully appreciate photography’s otherness, what is required is a new politics of reconstruction work (Hall, 1984) and new ways of thinking about photography, to recognise the significance when photography’s missing chapters are brought forth out of obscurity and into the domain of representation.

In 2017, I was introduced to the amazing photographs of Maganbhai Patel—known popularly as Masterji—who was Based in Coventry in the UK. His work highlighted the fact that Western scholars working in photography have been culturally blinded by their own reflections. Rather than acknowledging photography as being, from its first inception, a truly global phenomenon, Eurocentric curators and historians have focused on building a photographic visual regime that places the West above the rest.

Eurocentric photography is haunted by its own colonial psyche, and reading the history of European photography in the present tells us much more about the colonising eye than it does about the myriad foreign, othered subjects it focused on.

Photography’s history has been waiting for Maganbhai Patel’s work to surface. The idea that there was no one person from within the migrant body of Indian subjects journeying to Britain, taking up the camera to document the hopes and aspirations of the newly arrivant migrants marks a fault line in our understanding of the global appeal of photography, the migrant’s desire to record a new sense of being, and to have this new sense of self captured in a photograph and sent back home as record of having “made it.” Not merely to a new destination, but as modern subjects in the modern world, framed within their own terms as uniquely future-facing people with new and exciting identities (Hall, 1984), with the capacity to generate and circulate their own new images, purely for their own pleasure.

Masterji’s photographic practice is unique in the sense that he was clearly a photographer in tune with his community’s sense of time and place. In picking up the camera to record this hugely transitional moment in both British and Indian history, he considered himself and his family to be as much a part of this historical moment as the subjects he photographed. There is no great objectifying distance in Masterji’s practice; he is culturally in love with his subjects and his sitters become a portrait of an extended family that are bound together not through bloodlines but through the lens of his camera. Masterji’s photographs can therefore be read as intimate, quiet moments that operate between both the internal and external desires of the subject in focus. It is in these moments that his studio becomes a laboratory for future thoughts in which both the real and the imagined self can emerge anew in the new world.

In contrast to the work of Masterji, I also worked over a period of four years, with Mahtab Hussain on his project titled You Get Me? which Autograph exhibited in 2017. The project focused on the critical question of masculine identity among young working-class, British Asian men. This intimate series of portraits, produced over nine years, aimed to operate within the highly contested political terrain of race and representation, respect, and cultural difference. Hussain’s photographs examine how the weight of masculinity impacts the subject’s self, providing provocative visual moments that invite the audience to consider how young men and boys negotiate the complex social constructions of that have been historically placed on them.

What are some of the growing concerns for Autograph, especially at a time when social media has made us aware of a multitude of voices?

We have to recognise that we can’t be all things to all people. Social media is a complex space and I think in many ways small arts organisations will always be challenged by the frontiers that social media provides. I think one of the key things we understand here at Autograph is that it is essential to recognise that there is no one decisive moment, no one decisive history, and no one way of being—history is a shape- shifter and a time-bender. What we attempt to do through the programmes we build is respect the very idea of difference.

■

Mark Sealy is the director of Autograph ABP

Following pages from: Bangladesh 1971, Autograph ABP, 2008