Record/Resist: Sheba Chhachhi

If we are to read Sheba Chhachhi’s images in the post-colonial south today, we may need to reconsider their deployment and usage as well as questions of viewership, advocacy, and critique; the limitations of over-simplifying the framed object. These regimes of looking, of seeing, and being seen are intervened in most strongly in the photo-video installation she made in 2012, titled Record/ Resist. Her staged images alert us to how the process of “making” an image, or setting the stage, which involved a certain conditioning (a certain regime of perception), so as to most powerfully influence the audience. We might then ask whether Chhachhi’s images challenge viewership and construct a post-Independence discourse, which denounces wresting power from the subject, and thereby denounces traditional perceptions of viewing?

The modern history of photography in India speaks through the vocalization of personal statements and testimonies, a focus on the everyday and a heightened sensitivity towards questions of identity, gender, and race. The idea of enlivening disenfranchised and subaltern voices underlies this concept. Such aspects play out through Chhachhi’s studied consideration of her subjects, but they do so through orchestrated conversational and participatory modes – her interests in researching indigenous forms of feminism, being perceptive of the disconnections with the rural, and even absorbing the poetic/devotional modes of historical figures such as Akka Mahadevi (c.1130-1160), Lal Ded (1320-1392), and Karaikkal Ammayar, contribute to this process. The act of engagement with subjects is a scrutinized, contemplative consideration of how their lives come to bear on and in time; but simultaneously her own place as a documenter, assimilator, a constructor of histories, or an enabler of agency – one that is premised on exchange.

Chhachhi’s images perceivably connect to a more global phenomena – the workings of the women’s movement, or rather the feminist engagement with civil liberties and the need for new treatments of testimony and emancipation, fostering larger discussions around how images too can be agents of change; and the portrait, instead of becoming “iconic,” revises the canon of identity construction through an emphasis on the exceptional in the everyday. Chhachhi’s images have community-driven imperatives, evoking social movements everywhere that no longer need to be captured through a conventional reportage – the crowded streets or state brutality – but as staged, meditative moments (in both private and public settings) that arouse poetic and expansive ways in which diverse forms of cultural production in the contemporary, subconsciously lay claim to renewed motivations around image construction. That is how photography can be used to accentuate “positions” as we witness and bear witness to one another.

The creative juxtapositions, not only within the image, but as a series, invite a re-examination of the expectations of meaning and narrative construction of an image. That is, they also bring to light how documentary practices have enabled interdisciplinary exchanges with a focused scrutiny on ethics and methodologies by highlighting artistic motivations and outlays. What her images probe is whether the inclusion of narratives around the activists constructively change approaches to activism itself, and recast a certain stereotyping of activism as allotted only to the street and not the home or other familiar spaces. This entire complex of associations brings forth different modes of inquiry that have arisen through a careful engagement with marginalized subjects, not only in India, but the subcontinent as a whole – which in turn brings to light Chhachhi’s own placement and position as an enabler.

Is there a scenario here that translates imaging activism into lived experiences once more? Perhaps such a process may help to re-assess visual expectations, invert markers of stereotype, and thereby question the notion of a stable or authentic discourse? The images plausibly provide important subsystems and theorems around notions of conformity. But we may well ask, is it enough to acknowledge the positions from which Chhachhi

is speaking, and are these images in fact representative of the women’s movement as a whole; are they meant to be? In her own words, “Each woman is different. I am different with each woman. The notion of construction itself changes: the work is predicated on relationship.”

■

Sheba Chhachhi is a photographer, women’s rights activist, writer, film-maker, and installation artist. She is based in New Delhi and has exhibited her works widely in India and internationally. Issues centering around women and the impact of urban transformation inform most of Chhachhi’s site-specific installations and independent artworks. In 2017, she was awarded the Prix Thun for Art and Ethics.

Video still sequence from the installation Record/Resist, 2012

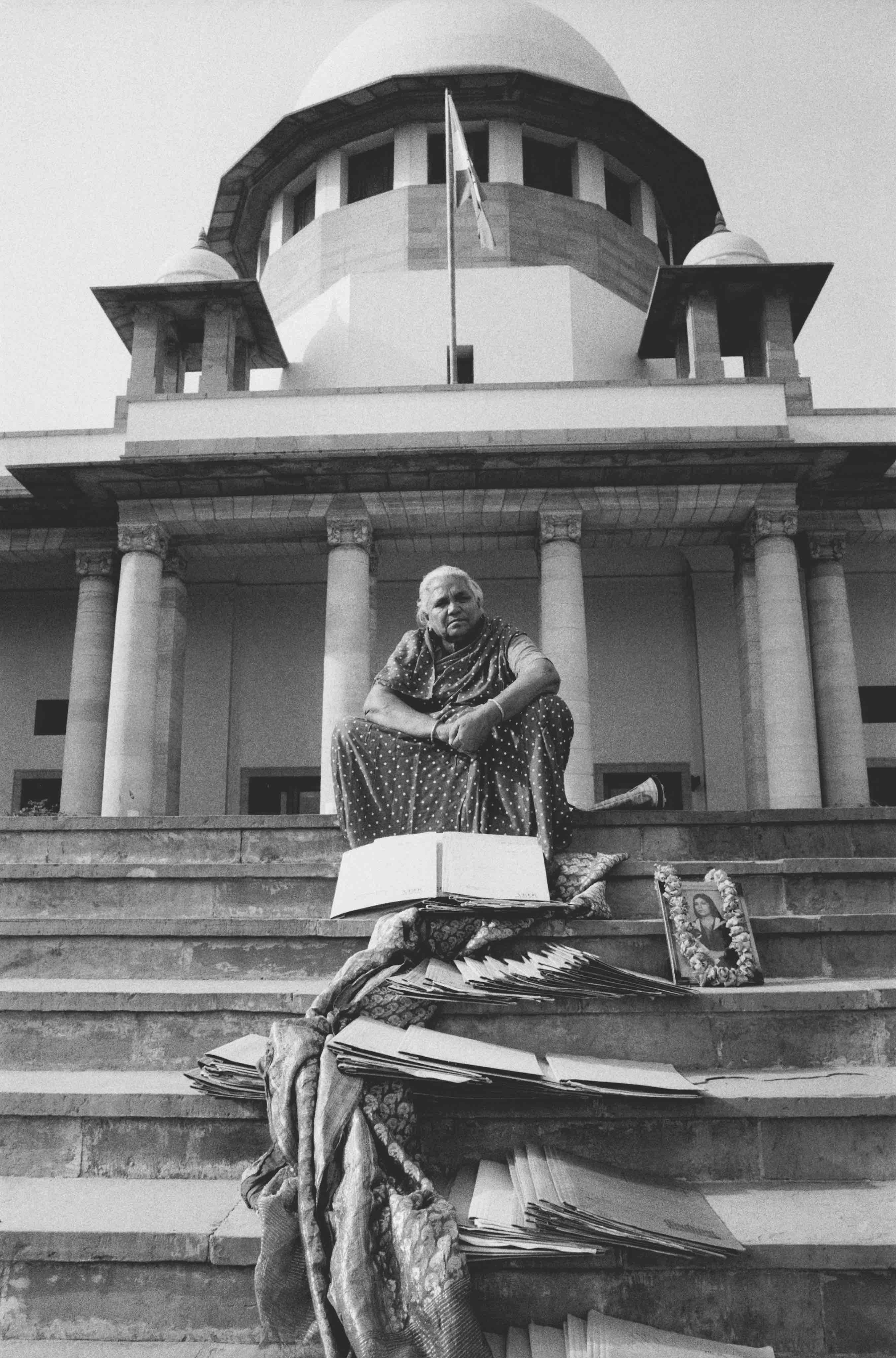

Sathyarani – Staged Portrait, Supreme Court, Delhi 1990; From the series Seven Lives and a Dream, 1980 – 91

Sathyarani – Staged Portrait, Supreme Court, Delhi 1990; From the series Seven Lives and a Dream, 1980 – 91

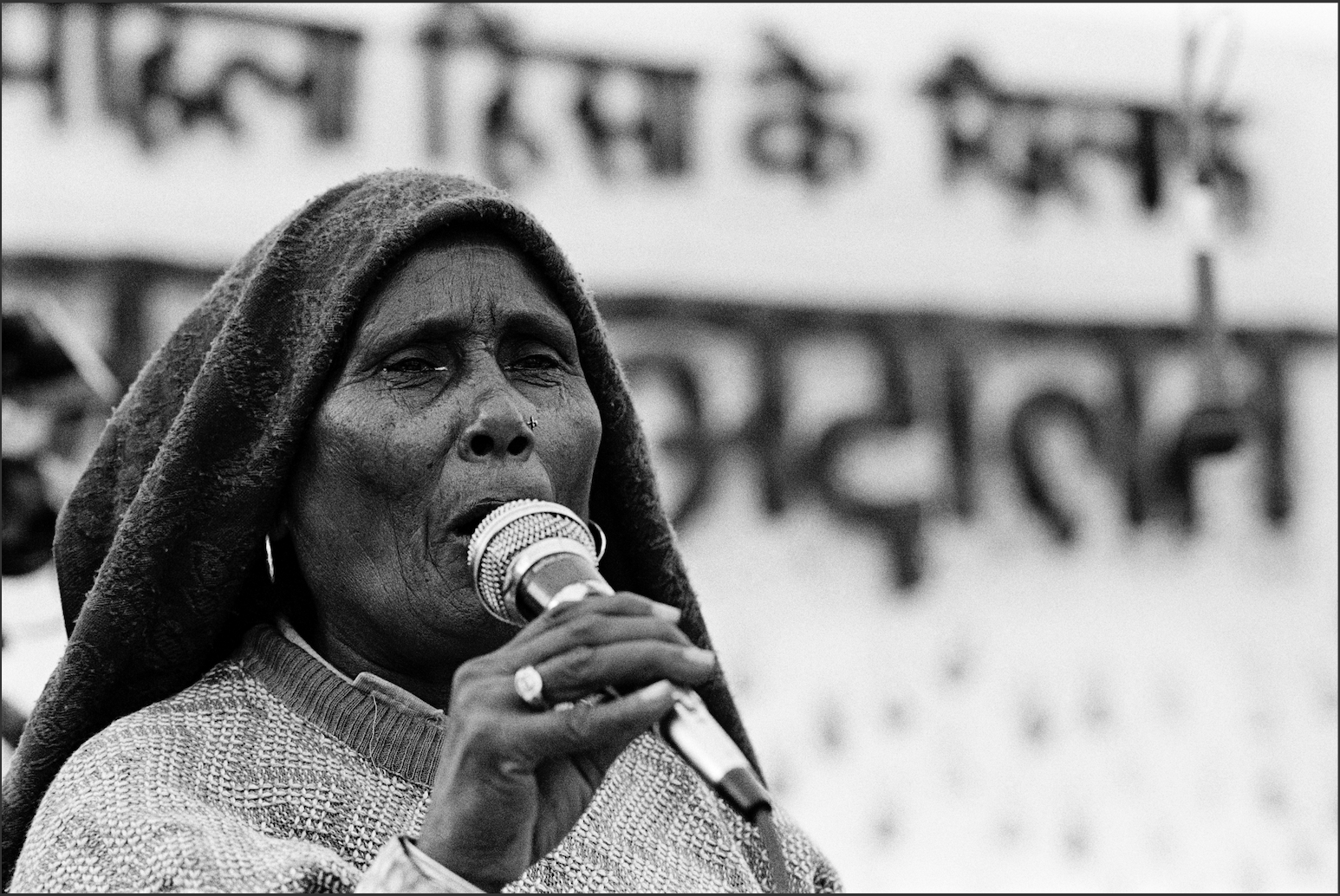

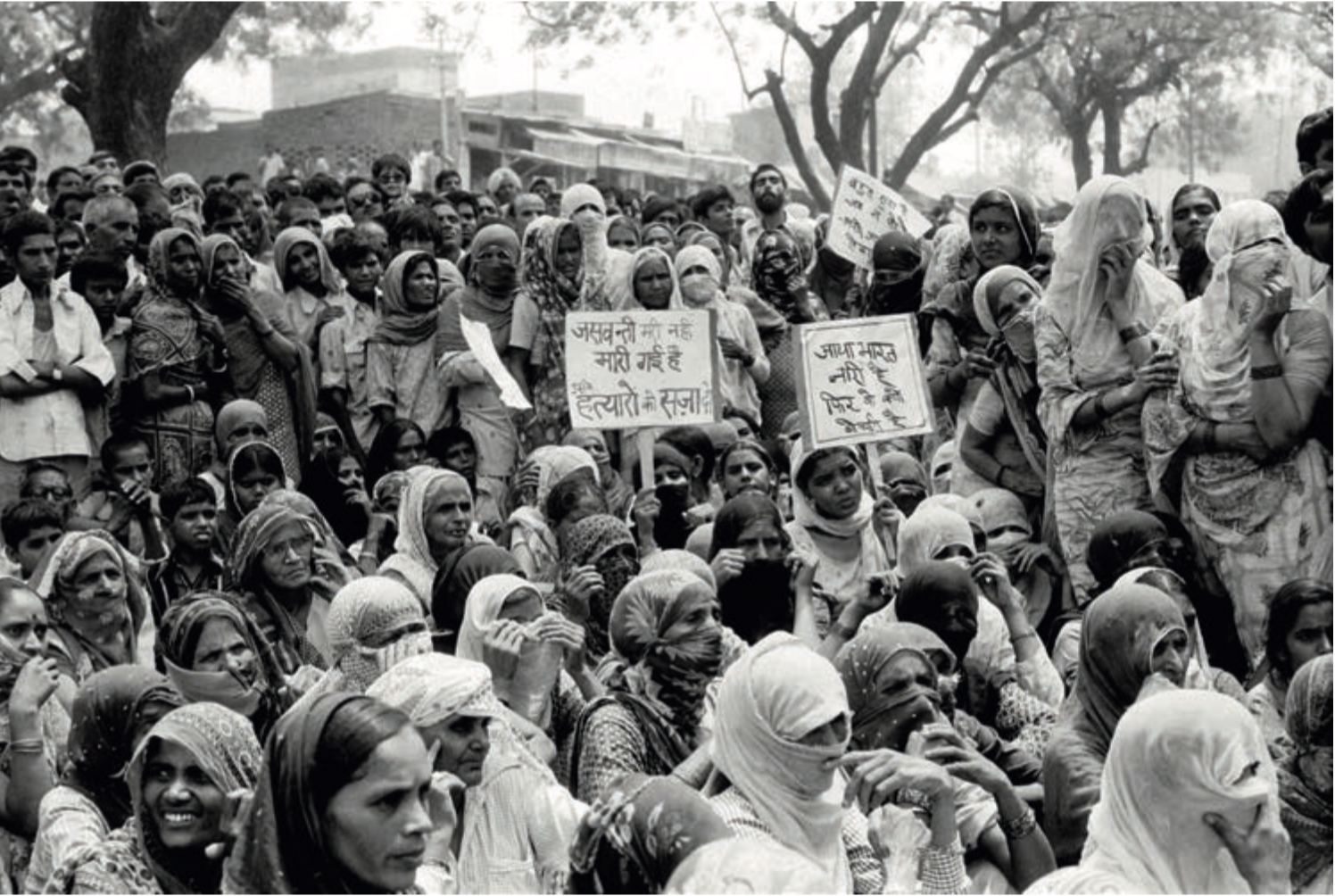

Above images from Record/Resist, 2012

Above images from Record/Resist, 2012

Record / Resist, installation view from the 9th Gwangju Biennale, 2012

Record / Resist, installation view from the 9th Gwangju Biennale, 2012 Still from Record/Resist, 2012

Still from Record/Resist, 2012