Tears on the Line

I’m a descendent of a refugee family. Both my parents and their families migrated to India from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in the post-partition period after 1947. Indian Independence resulted in a redrawn map along religious lines, a land transformed into territories and new nation states. In November 2014, I travelled to Bangladesh for the first time and had a strange feeling crossing the border and going through immigration. Bangladesh was the birth place of my parents and once the site of our own ancestral home, but Partition had changed the equations, seemingly erasing centuries of familial identity and essentially rendering my parents foreigners. Our family ties to the land felt severed forever.

My project is thus an exploration of borders and their impact on the lives of people who dwell in their vicinities—a fragile, violent, and uncertain world where one’s own national identity is debatable. Here, I attempt to tackle the critical questions about the way the idea of a border itself is enforced, and how the complexities of history confront the trivialities of a nationalist imaginary.

■

Partha Sengupta is a photographer who spends his time between Kolkata and Dhaka. His work explores borders and their impact on fragmented Bengali communities living along them, and has been shown at the University of Dhaka, and the Asian Heritage Council in Montreal.

All images from the series Tears on the Line

India and Bangladesh, 2015-2018

Film

In the last three years, Panchan Mondal has lost his two sons, the youngest a schoolboy killed by security forces during drills at the border. Neither apparent reasons nor any compensation was given.

In the last three years, Panchan Mondal has lost his two sons, the youngest a schoolboy killed by security forces during drills at the border. Neither apparent reasons nor any compensation was given.

Panchan Mondal walks through his field in the early morning to check the harvest.

Panchan Mondal walks through his field in the early morning to check the harvest.

Sanjeet Mondal, supervising his land for cultivation, twice suffered brutalities at the hands of the Border Security Force, and has since became an activist for others who have suffered harm by the BSF. Due to his advocacy, he is currently battling a case initiated against him by local police on charges of illegal smuggling. In the border area, the police and BSF are often hand-in-glove, issuing false cases to those vocally against them.

Sanjeet Mondal, supervising his land for cultivation, twice suffered brutalities at the hands of the Border Security Force, and has since became an activist for others who have suffered harm by the BSF. Due to his advocacy, he is currently battling a case initiated against him by local police on charges of illegal smuggling. In the border area, the police and BSF are often hand-in-glove, issuing false cases to those vocally against them.

When he was thirteen, Sanjeet Mondal was allegedly beaten by security personnel on the pretext of security measures while searching for smugglers. Five years later, he was again shot mistakenly and the pellets remain in his body. Sanjeet lives in constant fear near the border.

When he was thirteen, Sanjeet Mondal was allegedly beaten by security personnel on the pretext of security measures while searching for smugglers. Five years later, he was again shot mistakenly and the pellets remain in his body. Sanjeet lives in constant fear near the border.

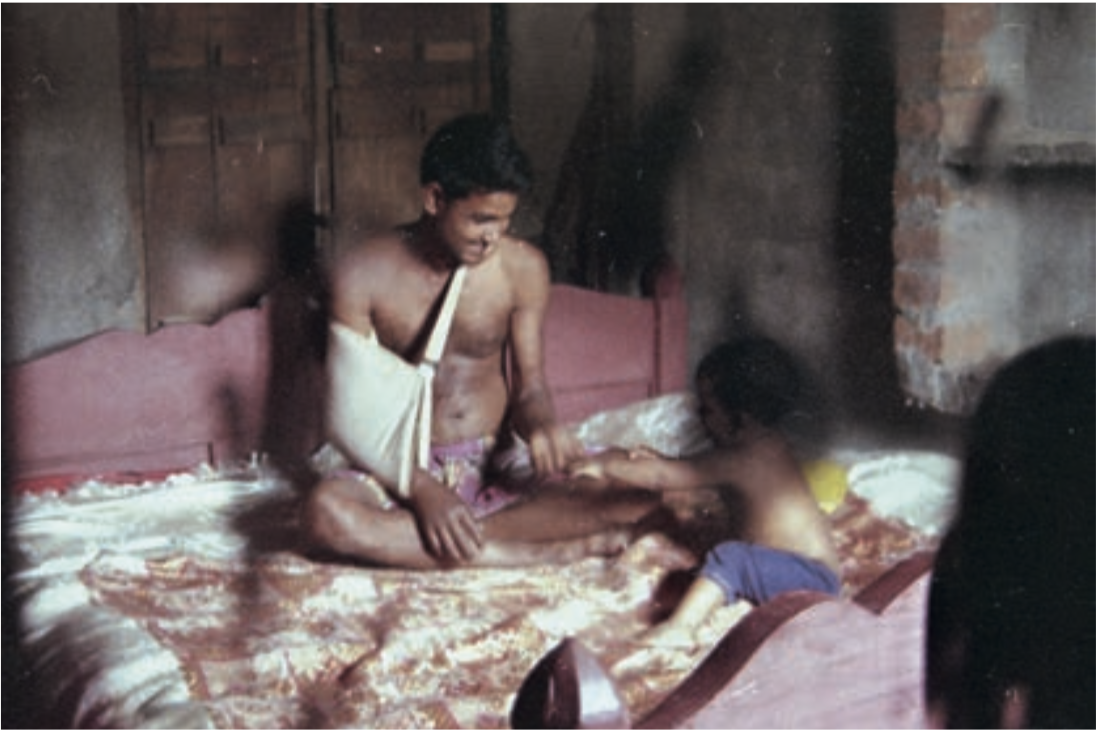

Ganapati Mondal was severely beaten and had his hand broken by security forces. He has limited finances for treatment. As a mason, he is unsure if he’ll be fit to work like before again.

Ganapati Mondal was severely beaten and had his hand broken by security forces. He has limited finances for treatment. As a mason, he is unsure if he’ll be fit to work like before again.

Hossain Ali, who was shot by Indian security forces on an evening when he was on his farmland supervising the field, is now crippled and can no longer work.

Hossain Ali, who was shot by Indian security forces on an evening when he was on his farmland supervising the field, is now crippled and can no longer work.

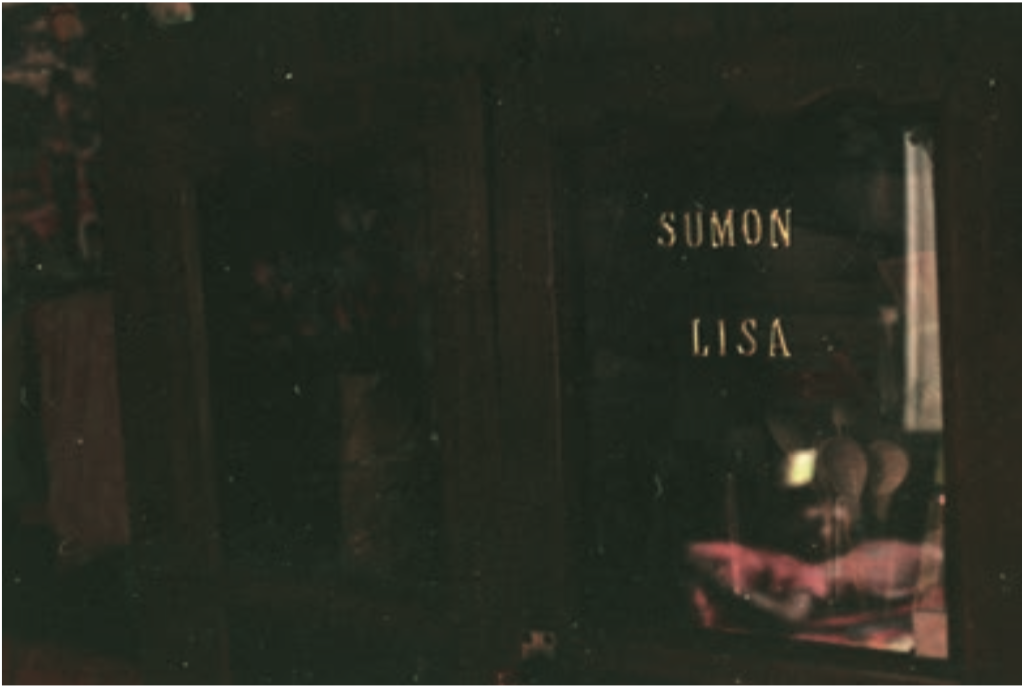

The almirah that bears the name of Suman Islam and his wife Lisa. Permanently paralyzed and without an eye due to ghastly physical torture by security forces, Suman was captured on his way home from a relative’s house one evening.

The almirah that bears the name of Suman Islam and his wife Lisa. Permanently paralyzed and without an eye due to ghastly physical torture by security forces, Suman was captured on his way home from a relative’s house one evening.

Saheb Bibi was seven months pregnant when she was beaten and manhandled by security forces in her own house in the name of a check, as her home is close to the border area. She had to spend several days in the hospital and continues to be haunted by the trauma of that day.

Saheb Bibi was seven months pregnant when she was beaten and manhandled by security forces in her own house in the name of a check, as her home is close to the border area. She had to spend several days in the hospital and continues to be haunted by the trauma of that day.

Eleven-year-old Bellal Islam was hospitalised two years ago when he was severely beaten by security forces on the pretext of flushing out smugglers from the border region. His education was hampered by his injuries and trauma. Young boys are often targeted by security forces, who think they are involved with cross-border smuggling.

Eleven-year-old Bellal Islam was hospitalised two years ago when he was severely beaten by security forces on the pretext of flushing out smugglers from the border region. His education was hampered by his injuries and trauma. Young boys are often targeted by security forces, who think they are involved with cross-border smuggling.