Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Dear Kesang

1 December 2020

Dear Kesang,

The word aparichit has always found such a morose yet lyrical tune attached to it. It is the word for stranger in Nepali—translating loosely as “unidentified”—and this is where my letter to you starts. We are unidentified, strangers to one another. And yet strangely, I am writing to you. Here I am, looking at your photographs and occupying your memories; we stand differentiated by time and space.

A close friend informs me that in Tibetan there is no literal translation for the word “stranger,” that “ngo ma shenpa” translates as “someone you do not know.” I do not know you and we are connected, but I am getting ahead of myself. Let me tell you why I am writing to you.

A box of your photographs found its way to The Confluence Collective to become, unwillingly, a part of their archive, and in their office was where we met. Laid before me was an entire lifetime of memories, which had been guarded over time and now they sat with more aparichits trying to make some sense of this entire life and community you belonged to. Martha Langford writes that the photographic album is “…a repository of memory” and “…an instrument of social performance.”[1] Here, I find myself immersed in these memories and social performances of someone else’s life with no connection to validate these instances. I hope you will forgive the insolence of this imagined narrative I have been piecing together, a narrative that is strangely as much mine as it is yours.

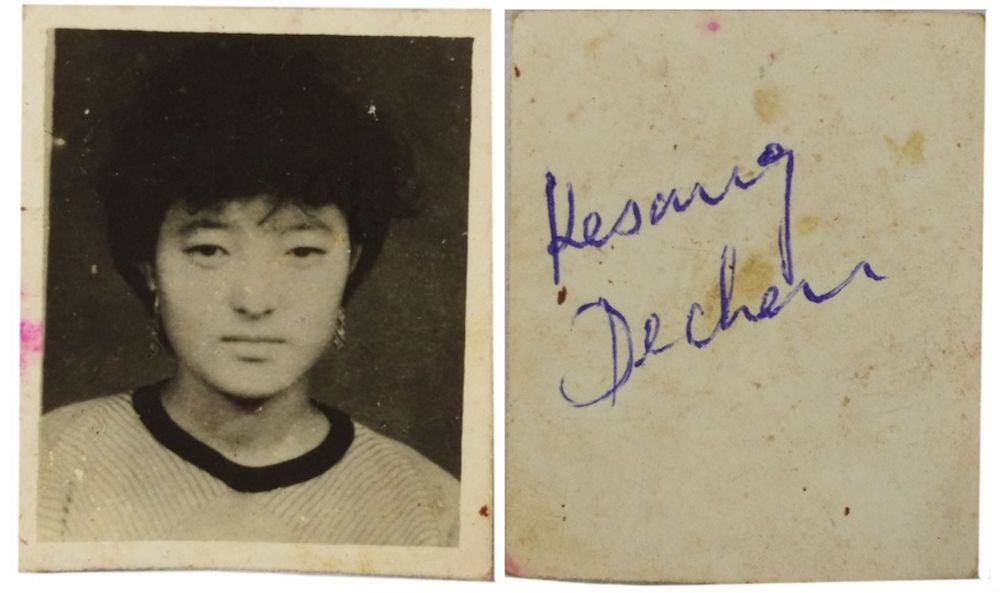

This photograph, in particular, became a focal point in attaching different strands of where and how you went about your life. With your name scribbled behind, it sounded almost like a declaration to the world—that this was you, forging a life for yourself, forging an identity. Sifting through the photographs, I found myself looking for your face; its familiarity almost reassuring among a sea of aparichits. Oddly, I found myself placing your image at the centre of the table while the other photographs formed concentric circles moving away from you. Your family formed the inner circle, while friends and other loose threads formed the other circles.

Langford goes on to write that sociologists recognize the mysteries that bind personal documents and tend to advise “…albums are virtually useless unless examined in the company of their compilers, or at least with members of their circle, who can interpret the social arrangements and signs.”[2] Sitting in the office or at home, looking over your photographs, I often found myself wondering if this act is rendered useless because you or the members of your circle cannot stand witness to this narrative of your life—that stands frozen in time, in these photographs. Is a photograph useless if there is no one to remember what it represents, or what it represented? The countless albums we accumulate, both physical and digital, what happens to them when we are no longer there to validate those memories? Do the stories behind each frame just dissipate eventually? So many questions have plagued me since my first encounter with your photographs. Oddly enough, it has resulted in a longing to preserve all those disintegrating photographs lying at home. What are we without our stories?

Stories constantly evolve around us, from person to person the same story manifests into another being altogether. Strangely, I was reading a novel by Amitav Ghosh and these lines jumped at me from the pages: “Only through stories can invisible or inarticulate or silent beings speak to us; it is they who allow the past to reach out to us.”[3] So, here were these fragments of your stories lying in the Confluence office. In your absence and the resounding silence that it brought, this need felt urgent: a need for your past to reach out to us. To tell us of the journey you might have started from my very own hometown, Kalimpong. To know your story was to understand my town a bit more.

Kesang with her classmates and headmistress, Unknown location, 1963.

Your photographs of boarding school were such a delight to view, from some scribbles behind a photograph we could identify that the school was located at Puducherry. It must have been an adventure, though not without its challenges. Here you are, in 1963, sending back a picture with your headmistress to your family, who I am sure were thrilled and anxious to hear about your life away from them.

Surrounded by peers, given an Anglicized education and away from home. You must have been around eleven- or thirteen-years-old here. It must have been a strange world to occupy and at such a young age; Puducherry is so different from Kalimpong, in its landscape and culture, not to forget cuisine. And I can only imagine, looking over the photographs sent by your friends, that you made quite an impact on people there.

Throughout this process, I wondered what you would have to say about these glaring questions I had: do memories fade away when there are no longer any people left to relive them? Were these photographs left by mistake or did they no longer hold value in a digitized world? The photographs belong to you, as do the memories; and what I do have in my possession is an imagined life. Can it be possible that I have even imagined your memories? Would you have shrugged off these questions and just told me about the adventures you had, the life you built for yourself? Possibly told me that stories are infectious, they find new hosts and new paths to attach themselves to and that is how stories move along, sustain themselves. Sounds utterly bizarre, but here I am, writing to you as I piece together an imagined narrative of your life, of your family and your adventures.

School play, Puducherry, India, Unknown date.

Family trip to Victoria Memorial, Kolkata, India, Unknown date.

I see that your father was a very loved man. Surrounded by his loved ones, on a visit to what looks like the Victoria Memorial, Kolkata. Did he tell you about his travels, why he came to live in Kalimpong of all places?

The picture of him taken in Beijing, in 1953, must truly be a treasured one. I cannot presume life must have been easy then and I am sure he must have found living away from his loved ones very difficult. Was this photograph sent to his parents or your mother, a physical reminder of his absence in their lives? It would have been accompanied by a long letter, I am sure, one telling them about how much he misses everyone and how hard he works to provide for his loved ones.

Your father (Image 4, below) and his brothers look different, but strangely enough, there is a familial bond that you can almost grasp and reach out to. Were you close to them? Would looking at their photos remind you of fond memories that you share, or possibly even sad ones?

Three brothers, Unknown location and date.

Kesang and friends, Unknown location and date.

These photographs and the placement of this lady in the centre made me wonder if this could have been your mother. There was something very soothing about her presence and the ease with which everybody surrounded her. Coming from a family of women who lead and comfort, I could not help but draw a parallel between my family photographs and the central position that my mother commands in them.

Women of Kham, Unknown location and date.

Did your mother or father share their roots with the Khampa women of Kham, Tibet? I presume, given how this photograph has been stored with your family album, that there is an attachment to your history and roots. The Khampa uprising against the Chinese in the late 1950s is well documented. While looking at this picture, I wonder if these women knew how their photograph would be etched in history as that of resilience and solidarity. One that would find itself linked to a collective memory that you share with your family.

The images of you are scattered in this pile sitting here, but there you are surrounded by your friends and half-hidden from the camera. Somewhat content at these relationships you have sealed and—I would like to think—maintained through the years. I draw parallels with my relationships and my aspirations to sustain them over the years, no matter where life might take me.

Often, while going through family albums, I am taken aback at how seriously we find ourselves being documented. As if a smile would untether the photograph, rendering all memory and activity pointless. The performance we put on often seeps into the enactment of our daily lives as well. Both these images of you allow me access into a small bit of who you were or could have been. Your chuba[4] signals a young woman coming of age and embracing her heritage, but also separates you from friends clad in a salwar kameez. It was interesting for me to find so many photographs of women clad in chubas. As I grow older, I have found a need to understand and appreciate my cultural identity. Often it is the same identity that we tended to disengage with when we were younger and eager to blend in with the diverse environments we occupy. However, in your photographs, this identity seeped in so wonderfully and boldly.

This photograph of your friends wearing chubas was so heartening to see, whether or not they were Tibetans, it embodied a sense of solidarity and curiosity for your traditions and culture.

Looking at the various photographs of women in their chubas got me to revisit an article I had read by Dicky Yangzom that discusses the role clothing plays in the context of movements like the Lhakar movement.[5] Clothing becomes crucial in understanding how communities can “…negotiate and maintain boundary through dress; how the embodiment of dress itself alters political space and civic discourse is imperative to understanding how resistance is performed in creating social change.”[6] While the Lhakar movement is a fairly recent one, impacted by the contentious history of China and Tibet, Yangzom’s work discusses the pivotal role that traditional clothing can play in establishing a cultural identity as a projection of the self and communal identity, especially in public spaces. While a lot of your photographs of family members, wearing a chuba, are located in private or domestic spaces, there are a few like the ones of you at school and of relatives travelling in their chubas. While Yangzom discusses it under the political construct of Lhakar, I began to view these chubas in your photographs through a similar lens of being seen by using the body to visually stake claim: both territorial and historical. What do our traditional clothes speak of, do they work to differentiate us from the other or to assert an appreciation or acknowledgement of a cultural identity? Once again, I digress, seeing the beautiful chubas in your photographs left me wondering how a young girl at a boarding school in Puducherry understands her history and tradition in a space far removed from her home. Elements from my traditional clothing, that I had no use for when I was younger, now have such an impact on my engagement with my culture and my appreciation for its uniqueness. Perhaps, this is where I find myself trying to forge links with your journey.

In attempting to map out the trajectory of your life, there have been glimpses of travel, joy and family bonds. What was missing were the challenges you would have had to overcome. Then again, when do we document such moments? Photographs have tended to function as indicators of family events, travels and momentous or happy occasions. They did not function as they do today, where we incessantly document anything and everything we see. The removed financial element of a film being developed, and our current reality of thousands of photographs saved on a drive somewhere has rendered the tangible value of a photograph worthless. It reads almost prophetically that Langford would state,

“The translation of an album poses an impossible task. Words, like photographs, are furious multipliers, a thousand for each picture, or so the saying goes. To match the photograph, every element in the picture (every propagator of codes) must be measured, weighed, and entered on a mental list, and that is just the beginning.”[7]

How, then, do I go about measuring and validating your album, this box of photographs that have found their way to The Confluence Collective? I am attempting to translate this narrative, in the hope that you or a loved one will find us and fill in these gaps.

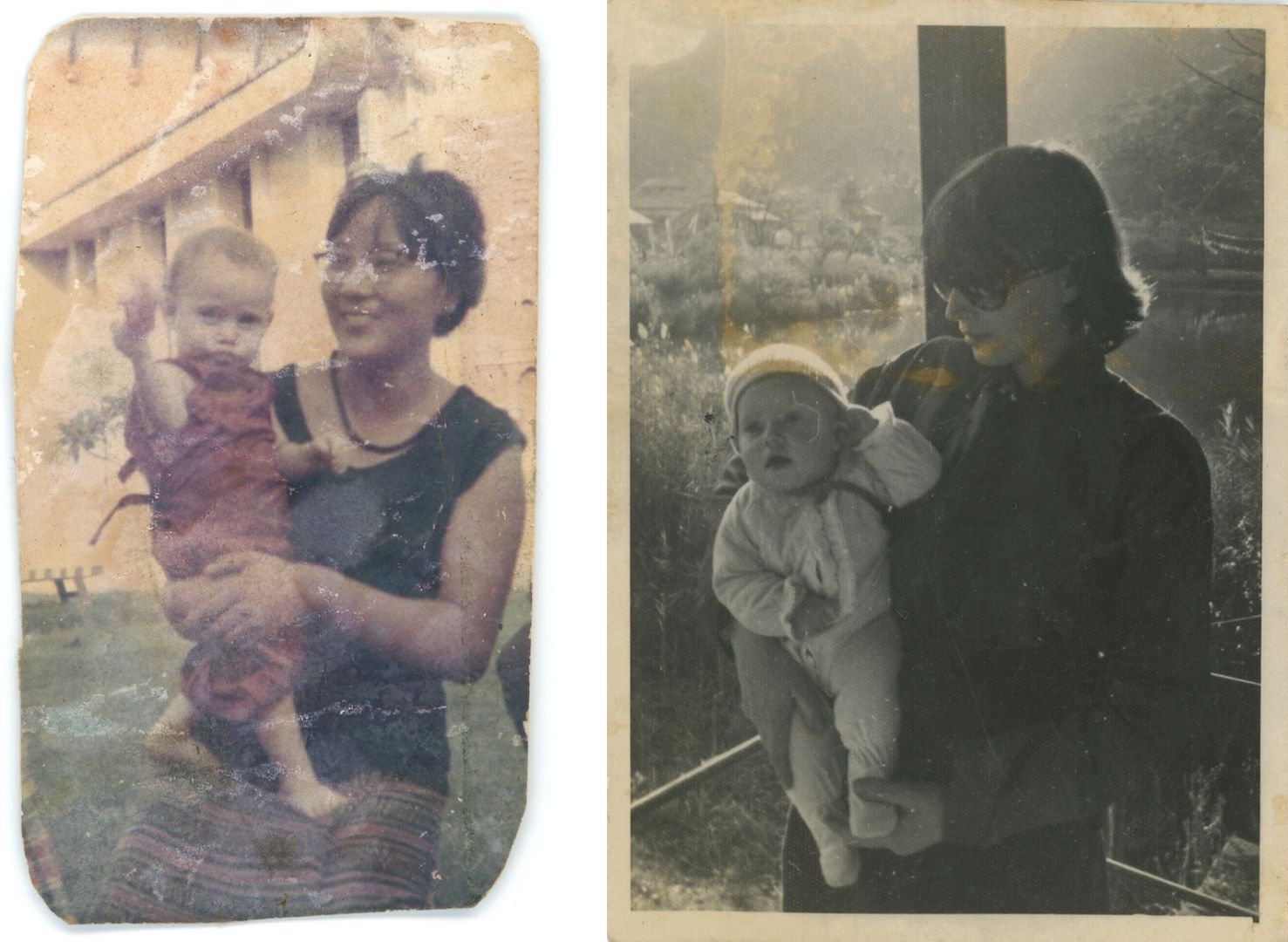

Left: Kesang with friend’s child, Switzerland, Unknown date.

Right: Friend and child, Switzerland, Unknown date.

Piecing together sparse details written on the back of some of these photographs, you have travelled or possibly lived in some of these places. The picture on the left—in relation to some other pictures in the box—show that you were in Switzerland, possibly working or travelling with the Tibet Institute Rikon, a Tibetan monastery situated in Zell-Rikon im Tösstal in the Töss Valley in Switzerland.

Rikon Institute, Switzerland, 1967.

The image below (Image 8) is dated back to 1967, situating your travels around this time. You must have recently finished school when this happened. Would this be a friend you made from the region? Or were you working with children through the Rikon Institute? Did Rikon become a home for you, again culturally so different from the spaces you have occupied? I cannot help but draw parallels again with my own life, wherein I have had to move to spaces so culturally different from my hometown—meeting people and forming support systems to cope with the lack of a family structure.

Children/ Nora and Gustav, Switzerland, 1967.

If you were linked with the Rikon Institute, what would have been your experience as you introduced spirituality to an audience so removed from the culture and values you were brought up with? Was it exciting, terrifying? Did it help you see how when you migrate you not only carry your identity but your culture as well? Did you feel like the other—exoticized or orientalized? How strange that these questions come to you through a letter from an aparichit? How strange that our lives are so far removed from each other, but that I understand what it means to be the other—in your own country and another. You have found yourself passing through and occupying, at different moments in time, different passages that have shaped who you are: from your family coming from Tibet to Kalimpong, then Puducherry, eventually your journey to Switzerland, and possibly so many countless journeys you would have made after that which are absent in this pile of photographs we have found.

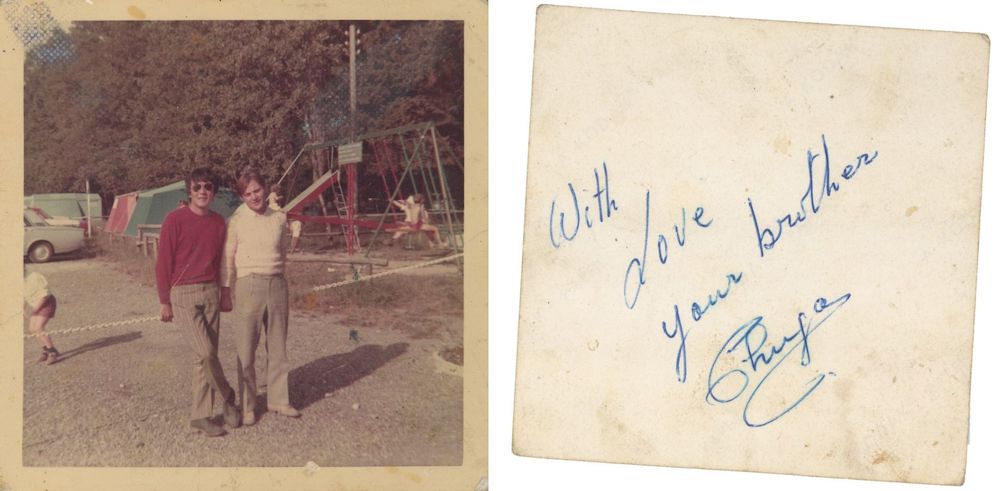

This memory of your brother must have stayed with you, is that how and why you travelled to Switzerland? (Image 9, below) Did he travel to be with you, or did you travel to start a new life? I am getting ahead of myself again. In piecing together this imagined narrative, I found myself moving across time and space. One minute I was with your family in Kalimpong and the next I was in Puducherry with your classmates. Memory is never linear, is it? It darts across time and reason. And despite an absence of me in this narrative, I was increasingly drawn to this experience of looking at the memories of another, but through a narrative I was imposing on them. This letter has taken a long route and it is all over the place, but before I end it, I thought companionship is a good note to end it on. I am sure you would love to see these photographs of your old friends, who loved you dearly. It is in this collection that I found a very relatable thread between us, for who does not understand the joy and sorrow of friendship and the companionship that comes with it.

Chuga and friend, Switzerland, 1967.

These photographs at the Old Lighthouse and on a beach somewhere in Puducherry evoke such playful memories of companionship and love. Your formative years were spent with these girls—learning and growing together—evident in the numerous images sent to you by friends who wish you would never forget them.

There is something so wonderful in these little notes left by friends who do not want to be forgotten, as if their image itself fell short of these resounding words beseeching you to hold on them.

It was an assumption that while you might have forgotten a friend, the photograph would stay with you forever. Are memories that impermanent, outweighed by something tangible? And yet, if you could not recount this face or memory, would it be rendered useless?

School trip to the Puducherry lighthouse, Puducherry, India, Unknown date.

I wonder what would have been if you and your friends were to meet today, would these photographs remind you of days that have long gone, or would you all rejoice in the memories they evoked?

These photographs and the little notes that accompany them stand suspended in time, waiting for you to relive them. As I sift through them, I cannot help but imagine a narrative of fun and mischief, of love and heartbreak, of sorrow and pain. After all, do we not relive these emotions so intensely when we are young and not as wary of the world.

Looking at these, I almost feel envious that I do not have such photographs embedded with memories sent by my friends. We share endless calls and emails as well as an occasional postcard, but the tangible photograph is one I am afraid we appear to have never shared. Our memories are attached to other things, digitally stored and guarded. They do not always feel like photographs that I can smell, feel, and pass around.

Coming back to Ghosh’s lines that it is through stories that invisible or silent beings speak to us; these photographs have opened a narrow crack into what your life must have been—a life of adventure, travel, challenge, love and migration. One that I am sure there will be plenty to discuss over, that is, hoping one day I have the opportunity to meet you or your loved ones. Till then I hope this letter and these photographs will reach you safely and find you well. I started by looking at your memories, hoping to piece an identity both individual and communal. What I then found myself going over repeatedly is: what does a family photograph do? Does it only maintain familiality, perform an individual or communal identity? Gillian Rose writes that when a photograph is put on display at home or a dwelling, “…they play an important role in producing that space as domestic: as a space for family.”[8] Your home and domestic space have constantly moved around with you, as have your memories. These photographs—spread out in the Confluence office in Kalimpong—have recreated an imagined space, one that is as aparichit as it is familiar. Through these photographs, I get a sense of the family you were a part of, the school that shaped you and there I begin to understand the woman that you became: one unafraid to visit new lands and form new relationships.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

Ruchika Gurung

Wendy, Kolkata, India, 1964.

All images by unknown photographers, Silver gelatin prints, courtesy of The Confluence Collective.

Ruchika Gurung is working at the University of Cambridge Museums, focusing on community engagement for their “Legacies of Empire and Enslavement Project”. She is an educator and researcher from Kalimpong, who strongly champions participatory and creative models of learning. Having completed her doctoral degree in Film Studies at the University of East Anglia, she has taught Media and Cultural Studies at universities and worked on numerous outreach and community-based projects in India and England.

The Confluence Collective are a collective of photographers and researchers working to create a common platform to bring together visual and oral stories of the Kalimpong and Darjeeling hills and Sikkim. The collective’s objective is to use visual mediums to rewrite and retell stories of the people, places and communities that make up these regions. Their archive aims to provide a space for photographs to be collected, digitized, catalogued, preserved and made accessible for academic, institutional, and independent researchers as well as practitioners.

NOTES:

1. Martha Langford. “Speaking the Album: An Application of the Oral-Photographic Framework,” in Kuhn, A. and McAllister, K. E., eds. Locating Memory: Photographic Acts. New York: Berghahn Books, 2006, p. 223.

2. Ibid., p. 224.

3. Amitav Ghosh. Gun Island. Gurgaon: Penguin Random House, 2019, p. 127.

4. Chuba is a national dress of Tibet, consisting of a long-sleeved coat-like garment worn by both men and women.

5. Lhakar was a nonviolent grassroots movement of civil resistance in Tibet after the uprising of 2008 that protested the colonization of Tibet by China. Dicky Yangzom writes that the movement “…was quickly adopted by Tibetans in the diaspora” and continues to be supported by the diaspora who observe Wednesday as a day to “…wear traditional clothes, speak Tibetan, eat in Tibetan restaurants, and buy from Tibetan-owned businesses.” Dicky Yangzom, “Clothing and Social Movements: Tibet and the Politics of Dress.” Social Movement Studies, (Vol. 15, Issue 6, 2016), p. 624.

6. Ibid., p. 623.

7. Martha Langford. Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001, p. 4.

8. Gillian Rose. Doing Family Photography: The Domestic, the Public and the Politics of Sentiment. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2010, p. 126.

Watch Ruchika Gurung talk about Dear Kesang:

View this post on Instagram