Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Dear Nani

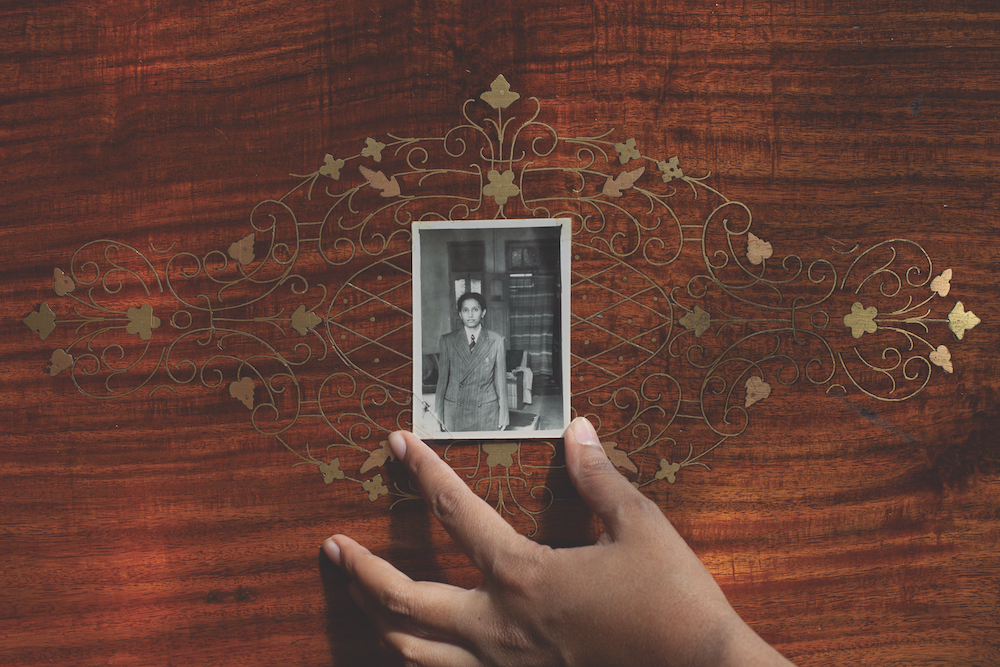

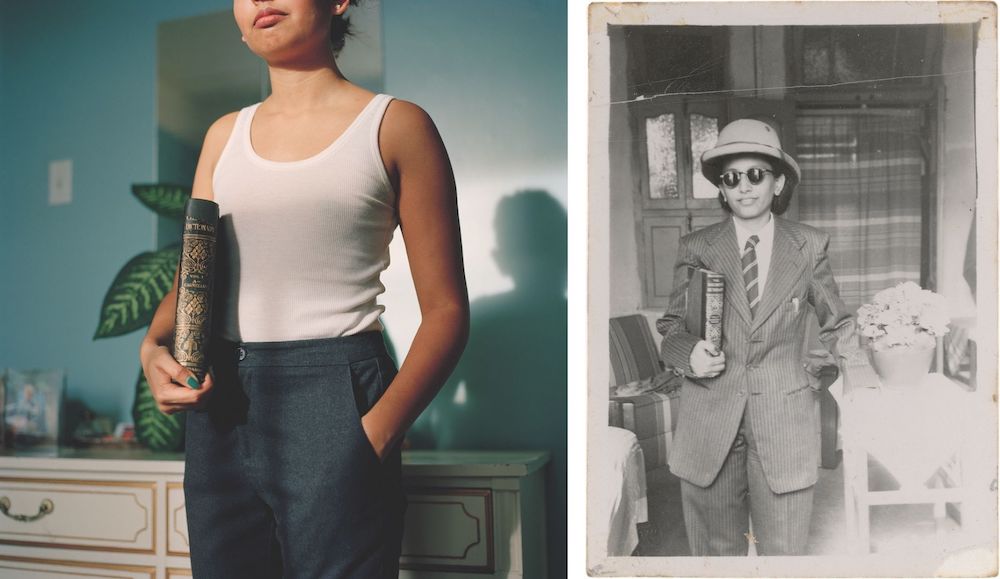

Zinnia Naqvi, Nani in Grey Suit, from the series Dear Nani, Pickering, Ontario, 2020, Digital photograph.

Every Mother a Cipher

I speak from the depths of the trunk

and dapples of light arise.

There is gold engraved on the surface,

vines that end in blooms

of no colour but wood, there is blood

a thread that spools inwards

a mother, a mother’s mother,

a distant garden where a breeze plays with

a cotton kameez, colours flicker in the air.

I speak for you ask

not to fill up the blanks.

Somewhere in my lifetime a sliver

of mirth was caught

so much of it is fingerlings

sifting through the sieve

which is now in your hands.

I speak but not really

fiddling the dials for a frequency in exile.

Youth is a strange gift

for a body, for a land

an arm once formed and flung in the dark

can grasp anything but itself.

I speak from the heart of this tome

you see me holding, my left hand ablaze

my body pinstriped and face begoggled

a sahib of the Company

a scholar of the East

I ate confidence from the air

gulped each ordinary ray

that dividing line on the coat,

that gilded spine you hold between

nails the colour of a well-trodden sea.

I speak without words

he is there on the wall behind me,

with mirrors, curtains, window panes, my iris:

the treachery of all things reflective

is to let meanings grow slowly,

naturally, like roses white as flames.

I speak from behind the thicket of a life

to that clear day in a garden in Quetta

limbs loose in the slow hours

the laughter of children flooding all crevices

stopping at my occiput, that land known to him and

to our home that once was in Karachi

brief, brilliant sparks in the sky

the other end of which you now hold,

revealing petal by petal,

journeys into ether.

I speak in our language

which barters chasms for sounds

breaks intent from knowledge

swaddles fiction with intimacy

our language is belated

but occasionalist, gathering in ravines

of a posthumous pulse.

I speak from your tensile screen

you are in the background and

pixels stitch your body to mine

as it is: a body from mine

scattered elsewhere, a place I do not feel

carried on a back I have pressed

a belly I have filled, hair I have

clutched, to braid into a song.

I speak because you ask not of origins

nor what survives of us

a flash and we are frozen

peering into a time we will not know

minutes slip into hours

unless a glass shatters somewhere

or life appears as a gift, an invitation to play.

You do not ask for the rules

you ask only to join in.

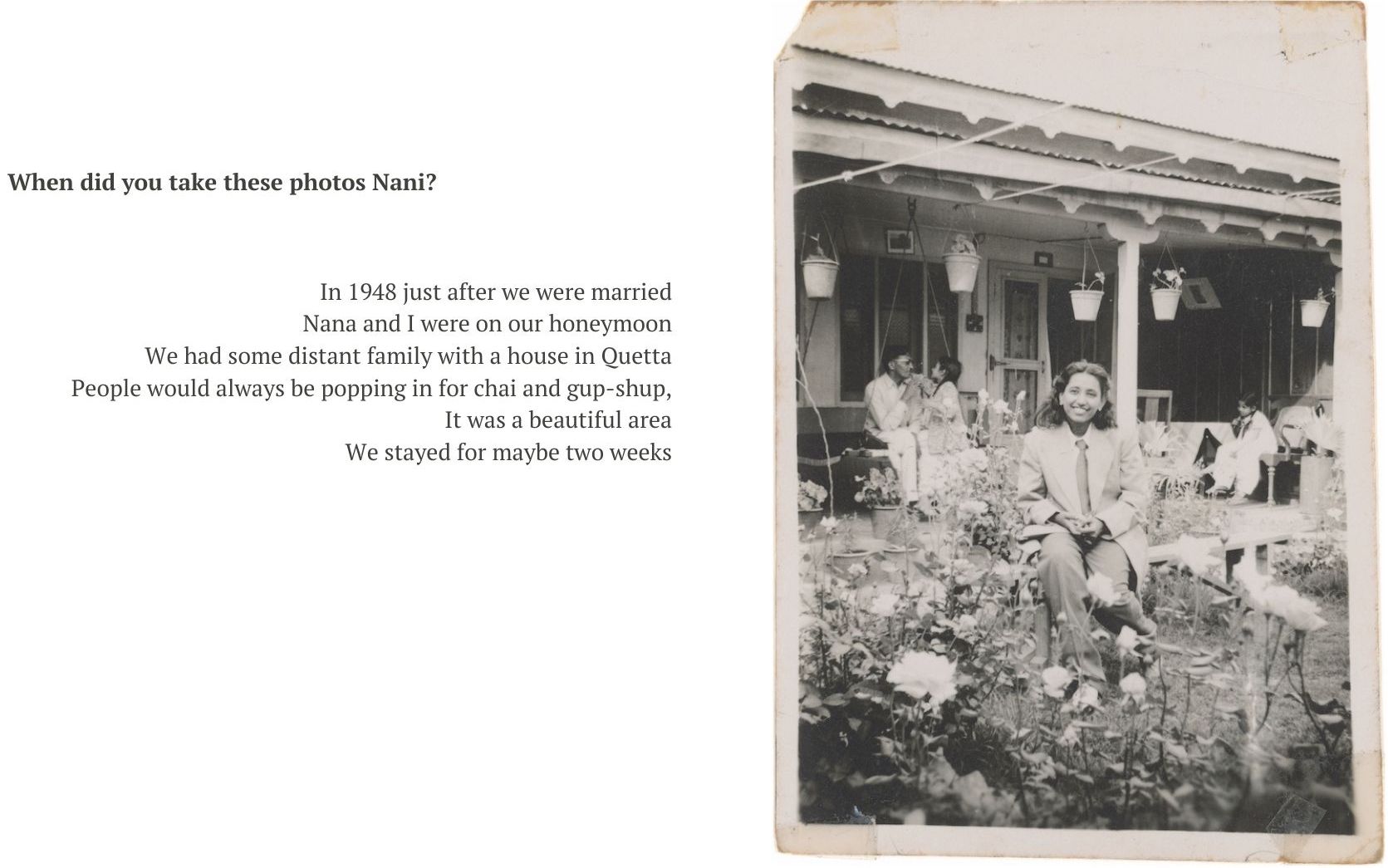

Nani in the Garden, Quetta, Pakistan, 1948, Silver gelatin print.

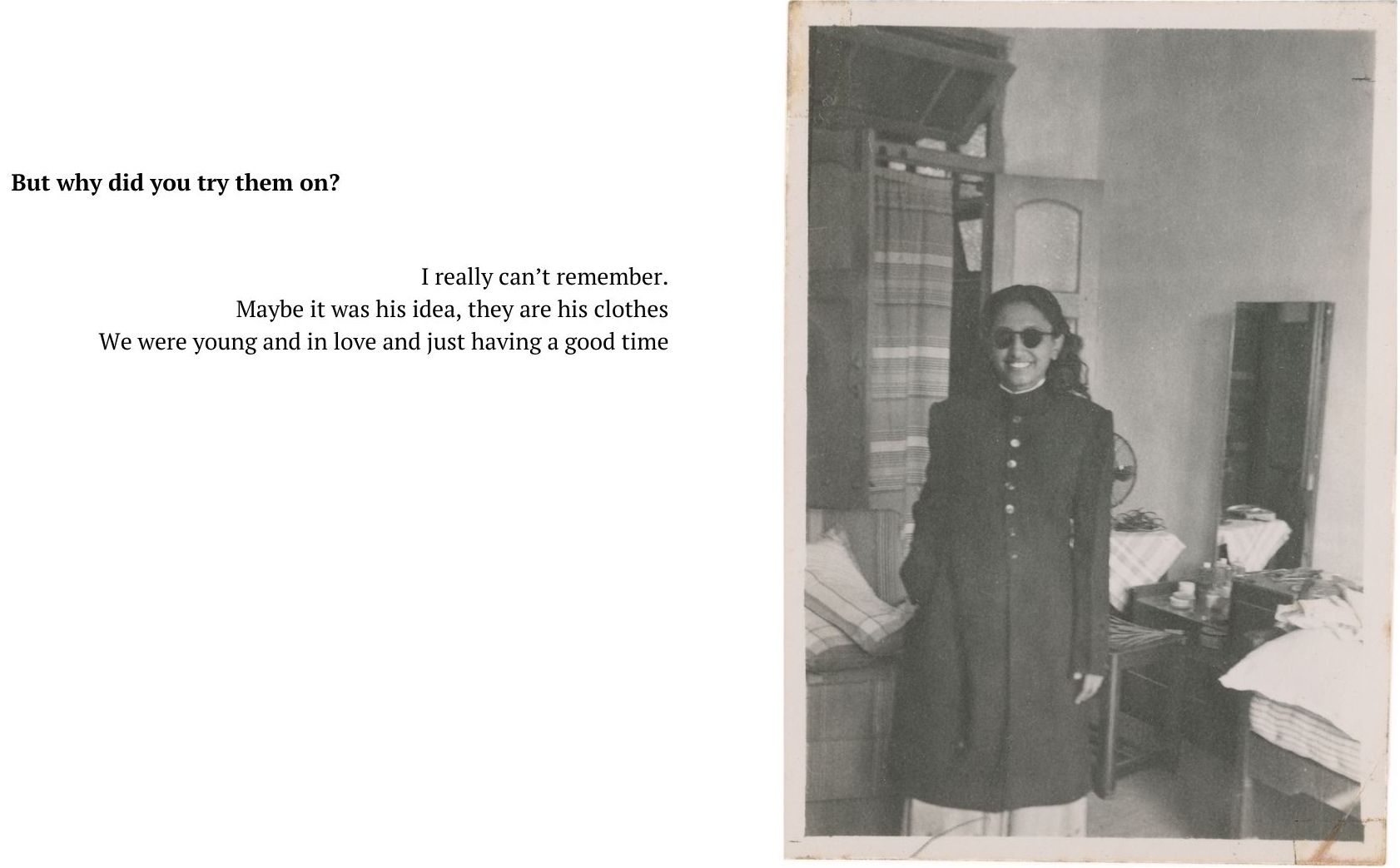

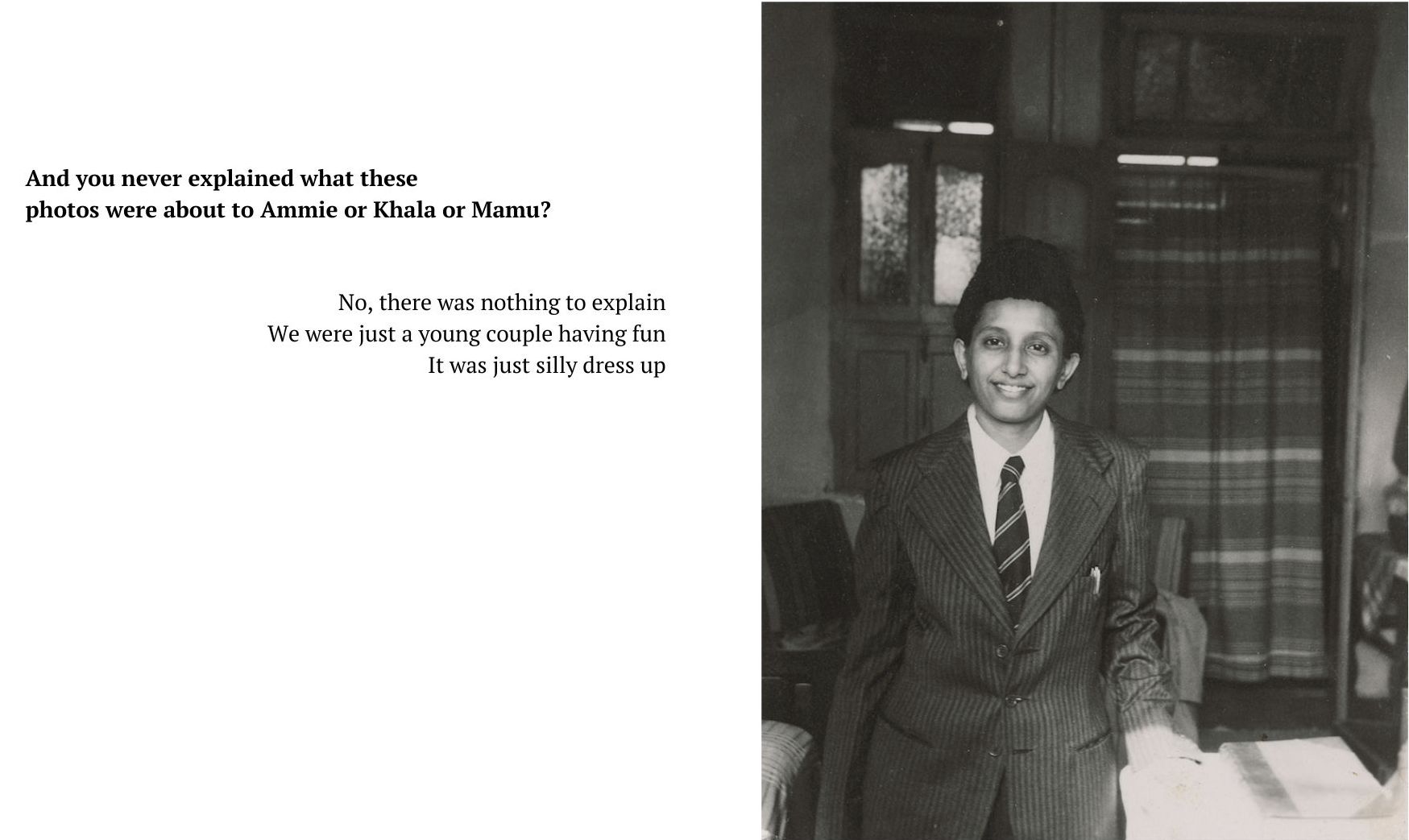

Dear Nani (2017-ongoing) is a project that addresses issues of gender performance and colonial mimicry through the family archive. The photographs included in this project are of my maternal grandmother (Nani), Rhubab Tapal, who cross-dressed by wearing different outfits that belonged to her husband. The photographs were taken in Pakistan in 1948—initially, on her honeymoon in Quetta, and later, once the couple were living in Karachi. My grandfather or Nana, Gulam Abbas Tapal, is the photographer and presumed orchestrator of the photo sessions.

In one of the frames, Nani holds a children’s encyclopaedia produced for subjects of the British colonies, performing the multiple roles of an Indian man who, in turn, performs the role of a British man. These varied strands then inspired me to take on the role of Nani, adding another layer to the impersonation. The fictional dialogue between Nani and me attempts to unpack some of the questions surrounding these images, while also asking the viewer to revisit their own reading.

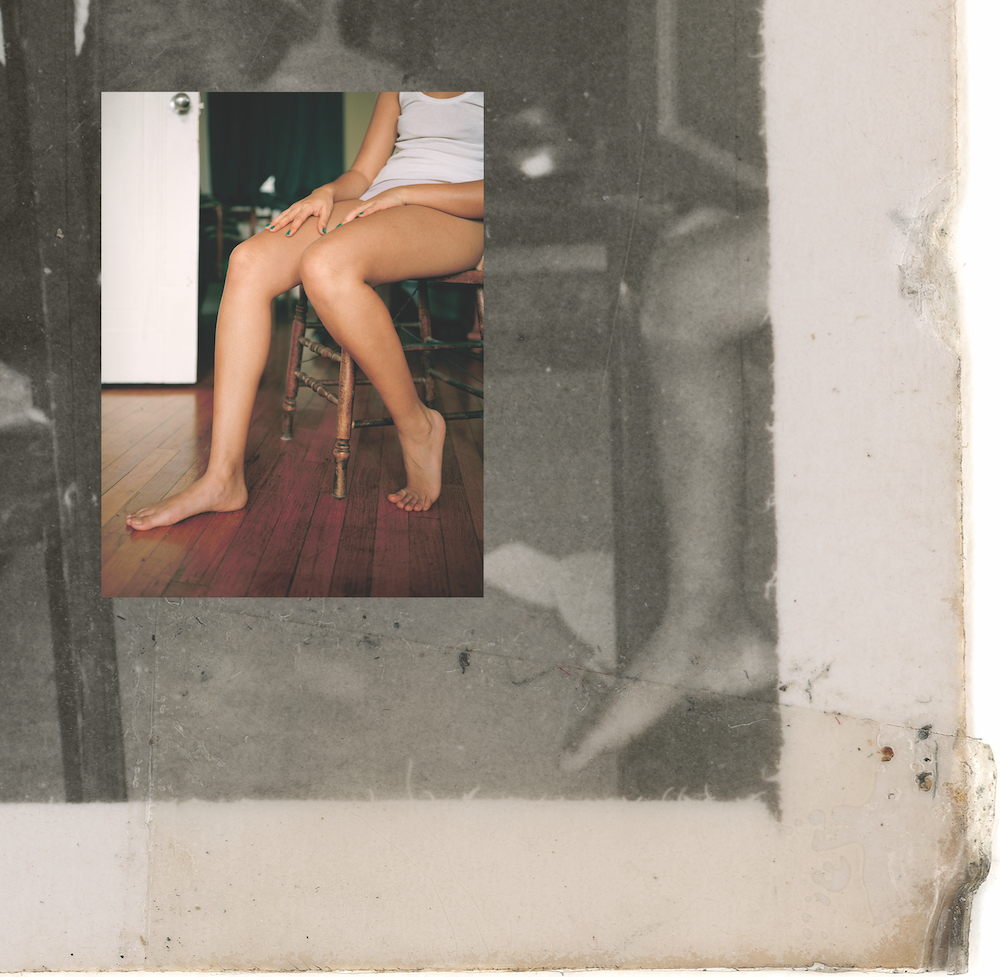

Children make an appearance in many of the found photographs of Nani. They appear in the background, playing or simply looking at Nani and Nana. At times their faces are visible and, at times, they are not. In the image of Nani in the garden, two young girls with long braids are clearly visible, playing with a paternal figure. They are not looking into the camera, nor do they seem particularly interested in what my Nani and Nana are doing. In other images, we see bodies of children hiding behind pieces of furniture. They are passive bystanders in the gendered performance, watching curiously. I imagine these children looking at my grandparents, observing what these adults are doing and perhaps wanting to take part themselves.

I see my position in this project akin to the position of these children, as someone who is looking and attempting to make sense of this performance. For this reason, I have created self-portraits in which I am re-enacting the poses of these children. Often my figure is only partially visible, or out of focus in the background. I do this to keep the focus on the original artefacts, but also to address my hand in bringing these images to light and unpacking their significance. In some of the self-portraits, I wear a white ribbed tank top, or banyan as it is called in Urdu. I chose to wear it because it is something that my father still wears as an undershirt, and I used to wear it too as a child, before I reached puberty. To me, the banyan represents a state of being in one’s body that is at times masculine, feminine, and childlike.

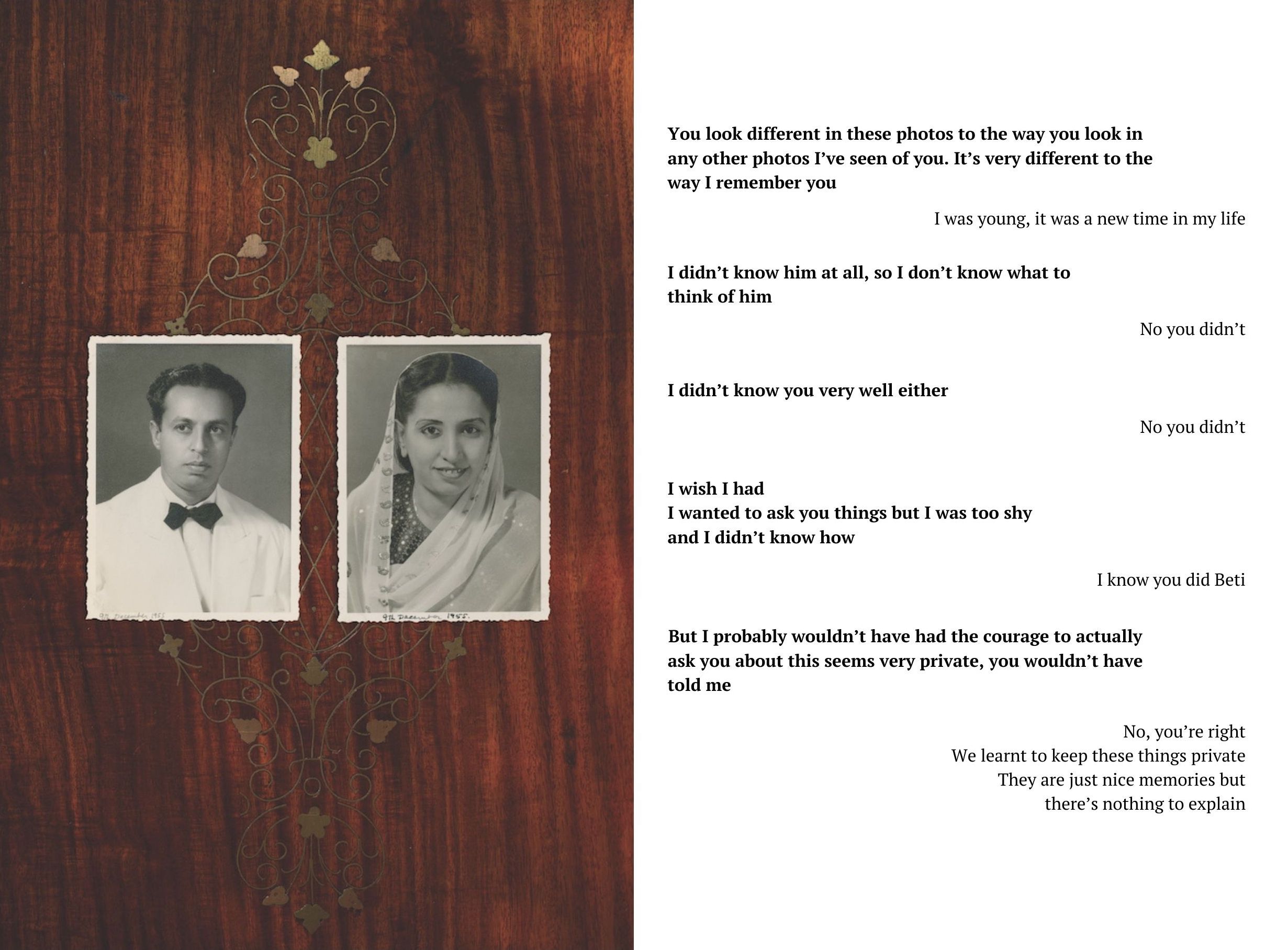

From my perspective of working in the West, I see these images as complicating what we expect historical images of South Asian women to look and behave like. But as a daughter and granddaughter, I see evidence of a young couple at the height of their love for one another. There are socio-political layers beneath this act or performance, but alongside them runs a current of romance, youth and liberation, as well as the hidden lives of our elders, which children do not often have the opportunity to witness first-hand. Through these images, I can interact with a version of Nani that I did not have access to in my life.

Nani in Black Sherwani, Karachi, Pakistan, 1948, Silver gelatin print.

Self-portrait as unknown child, Montreal, Canada, 2017, Medium format film.

Left: Self-portrait as Nani, Montreal, Canada, 2017, Medium format film. Right: Nani in Safari Hat, Karachi, Pakistan, 1948, Silver gelatin print.

Nani in Jinnah Cap, Karachi, Pakistan, 1948, Silver gelatin print.

Self-portrait with Nani in the Garden, Pickering, Canada, 2017, Medium format film.

Portraits of Nani and Nana in Karachi in 1955, Digital photograph of Silver gelatin prints.

Zinnia Naqvi is an interdisciplinary artist based in Tiohtià:ke/Montreal and Tkaronto/Toronto, Canada. Her work examines issues of colonialism, cultural translation, language, and gender through the use of photography, video, writing, and archival material. Her artworks often invite the viewer to question her position and working methods. Naqvi’s work has been shown across Canada and internationally. She is a recipient of the 2019 New Generation Photography Award organized by the Canadian Photography Institute of the National Gallery of Canada and was awarded an honourable mention at the 2017 Karachi Biennale in Pakistan. Naqvi is member of EMILIA-AMALIA Working Group, an intergenerational feminist collective. She received a BFA in Photography Studies from Ryerson University and an MFA in Studio Arts from Concordia University.

Arushi Vats is a writer and poet, who lives in New Delhi. She is the recipient of the Eyebeam and Momus Critical Writing Fellowship 2021.