Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Diasporic Rhizome: A Site for Intergenerational Work

Asma Kazmi, Building the City of Exiles, 2020, Digital video still. Image courtesy the artist.

Diasporic Rhizome was an online exhibition organized by the newly established South Asia Institute in Chicago. Put together through an open call for art works, it was juried by artists Brendan Fernandes and Faisal Anwar along with curator Ambika Trasi. The exhibition brought together twenty-one contemporary practitioners from varied backgrounds with diasporic connections to South Asia. A rhizome is a living structure—freely associating and attaching itself to new networks. Drawing on this dynamic model, the exhibition paid attention to the present moment—that of a post-pandemic paradigm of working and enlarging social circles online. The idea of a rhizome also echoed a renewed urgency to create a community and foster spaces from which subaltern histories and futurity could become anchor points, instead of being peripheral and isolated narratives within a largely Euro-American model. Trasi, in her concluding remarks in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition asks, “How does one unmap a region? How does one uncoil rigid and hegemonic understandings of ‘the diaspora’ and ‘South Asia?’”

As one moves through the individual works that range from films, immersive web environments, to image-based as well as performative narratives and so on; different nodes light up in relation to one another. Queer histories of South Asia sit together (uncomfortably) with neoliberal imaginations of its diaspora in the West, religious iconography meets with the aesthetics of the digital vernacular to create a necessarily unclear picture of a counter-future.

Multiple artists in the show articulate questions of identity through detailed investigations of their own histories, families and communities. Intergenerational work in the form of realizations, discoveries and mapping underlie the motivations and practices of artists like Renluka Maharaj, whose photograph Because of You, I Am featured in the exhibition. The photograph is a portrait of her daughter in a sari, set against an archival image of an unnamed woman from India who was a part of the forced migration of indentured labour to plantations in the Caribbean Islands in the nineteenth-century. In conversation, Maharaj talks about her own history and how her grandparents were sent to Trinidad and Tobago under similar conditions. Maharaj’s larger practice consistently dives into these immediate questions of identity and generational memory—Who am I and where do I come from? Her work pays homage to these ancestors who suffered and survived a complete uprooting of their culture, community and history due to colonial violence. Drawing out these histories even from unclassified images belonging to private and state archives, she attempts to reclaim the narrative from the Western colonizer and tell a different story—one of grief, loss and survival. Through iconic image-making, Maharaj’s work attempts to heal the cracks and gaps in history—both personal and colonial.

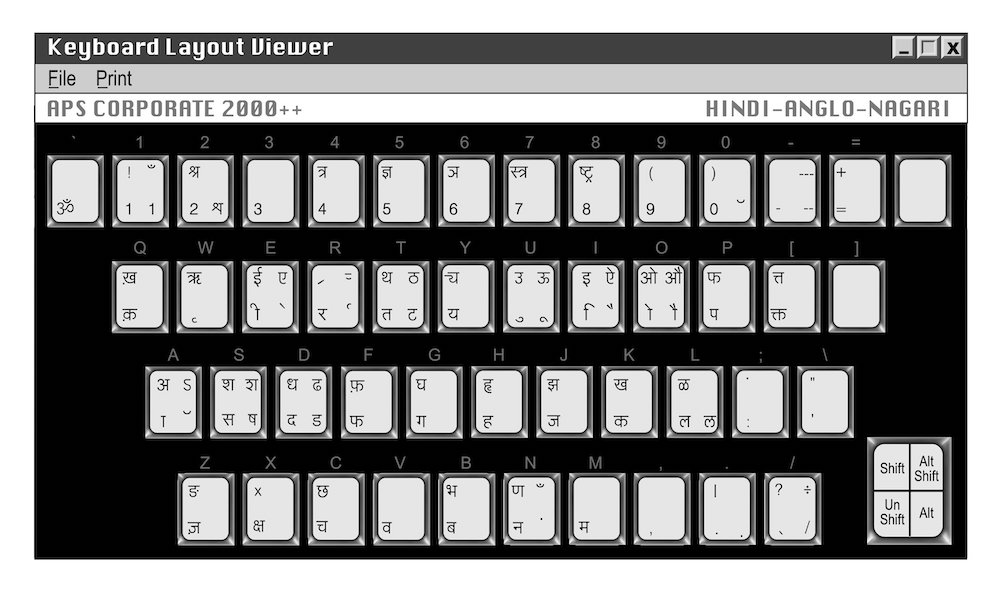

Another project featured in the exhibition, FONTWALA, memorializes more recent cultural history and pays homage to the beginnings of vernacular digital culture in India. The collaborative work between Shubhra Prakash—a first generation American theatre artist—and her uncle, Rajeev Prakash Khare—a typographer and early creator of fonts in Indian scripts—tells the story of local invention in the face of the globalizing force of techno-capitalist industries. While popular commercial operating systems like Windows and Mac OS have grown to support a wide range of languages, the early 1990s presented a unique challenge by pushing many South Asian languages to make the transition into digital interfaces. One of the key factors in this transition from analogue to digital was the work of typographers and entrepreneurs like Khare, whose software company created customized programs and adaptable typefaces using the newly standardized English QWERTY keyboard. This small-scale business was short-lived and eventually taken over by large corporations like Microsoft, who established new universal standards by the 2000s. However, their collaborative project archives and recounts this elided history through multiple informative videos and aesthetic explorations of Devanagari typefaces, as well as workshops and pedagogy around vernacular scripts.

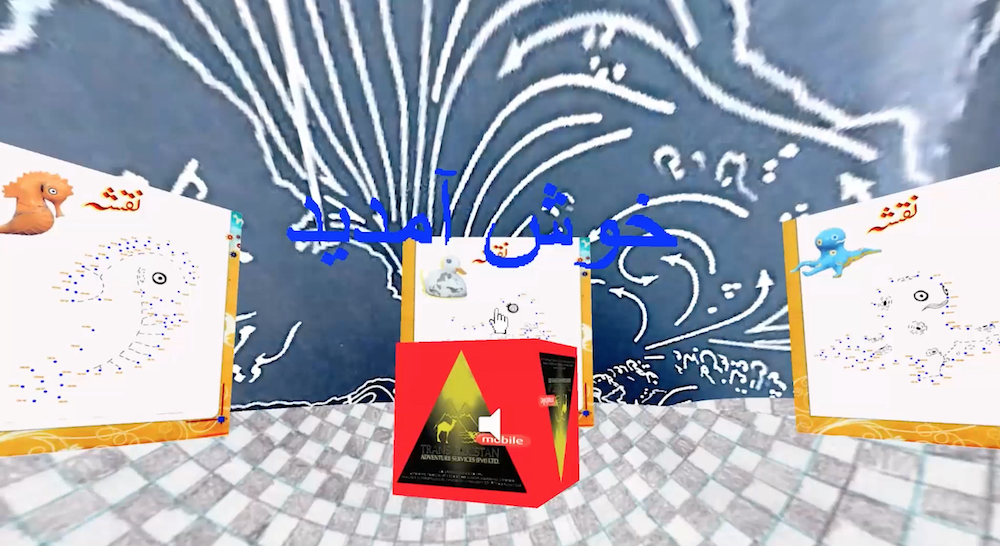

Living intergenerational stories of migration are further explored by Umber Majeed’s interactive web project Fotocopy.net, which draws upon archives of her uncle’s failed tourism company Transpakistan. Founded in the 1990s, Transpakistan—like many other South Asian travel businesses—fostered a particular narrative imagination of the country, directed predominantly at foreign travellers as an undiscovered ecological and cultural melting pot. Brochures and literature that she discovered bring forth Pakistan’s landscape of mangroves, deserts, mountains and forests—each with their pristine beauty.

Majeed’s web environment imagines an alternative Transpakistan. The project attempts to disorient—and then reorient—the viewer within a virtual space, as it exists outside of geographical boundaries, while drawing upon aesthetic and cultural strategies from the lived ecosystems of the homeland. While Majeed was born in the United States of America, her family relocated to Pakistan after the repercussions of heightened racial prejudice towards the Muslim diaspora in the USA following 9/11. In an interview, Majeed shared her experience of moving back to the “motherland” as a formative encounter, where she witnessed the transformation of Karachi’s landscape into a vision of neoliberal cosmopolitanism as imagined by a new Pakistani middle class exposed to global media and Islamic cultures in the gulf and Western countries. Majeed invokes anthropologist Ammara Maqsood’s idea of the “return migration”¹ in the aesthetics she explores—a kind of hybrid national identity where private land acquisition and illegal construction projects are aided and enabled by the state while being justified through the need for development, progress and “globalization.”

Renluka Maharaj, Because Of You, I Am, 2021, Digital photograph. Image courtesy the artist.

The last decade has witnessed a definite rise in hyper-nationalistic sentiments within South Asian diasporic communities (especially in the USA). It has resulted in the creation of a new stakeholder in national politics with considerable socio-economic and lobbying powers. This form of diasporic nationalism, according to many contemporary artists and thinkers, is rooted in alienation and nostalgia—the desire to belong and the memory of a once harmonious time. In her book The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym warns of the destructive power of this sentiment, “The nostalgic desires to obliterate history and turn it into a private or collective mythology… The nostalgic is never a native but a displaced person who mediates between the local and the universal.”² We continue to witness the erasure of histories and living communities as divisive nationalism dominates the political landscape across the world.

In the work titled My Goddess gave birth to a Goddess, Indrani Ashe, also a Founder of the Berlin Diaspora Society, speaks to the experience of longing for an unknown home. The work draws from the aesthetics of B-grade cinema, the lives of local entertainers and sex workers in India, as well as iconography of Hindu goddesses to create mythological beginnings for the artist’s own displaced identity. Ashe was born in the USA and was separated from her Indian mother very early in her life, growing up in a Christian family in North Carolina. In an interview, she talks about encountering images of Hindu gods and goddesses when visiting her aunt. Besides books, films and access to Indian stores and businesses in the USA, this was one of her only routes of access to India. Her work and practice therefore emerges from this state of dislocation—being marginalized in her home country (the USA), while having only fleeting images of her place of origin (India). In such a situation, she refers to her work as a “necessary mythology”—a strategy for survival, rebellion and futurity.

Umber Majeed, Fotocopy.net, 2021, Digital video still. Image courtesy the artist.

The idea of diaspora as a marker for alter-identity, then, holds radical potential to reorient oneself to a heterogeneous world. Ashe describes it as a “…collective no place for all the people that do not belong,” much like Brendan Fernandes, who describes queerness as, above all, a “…marker for self-inclusivity.” These notions find kinship refuge and convergence in the diasporic rhizome as artists simultaneously visualize their absent pasts and unwritten futures.

After Party Collective, some dance to remember, some dance to forget, 2020, Digital video still. Image courtesy the artists.

After Party Collective, in their video work some dance to remember, some dance to forget, explore these tensions between the written and unwritten, the law and lived realities. The work is an overlay of an extended performance of gender deviant bodies, sexualities and intimacy between the artists, together with textual excerpts from the landmark NALSA vs Union of India judgment passed by the Supreme Court of India in 2014. The collective’s statement reads,

“The judgment unconditionally allows for the self determination of gender including a non-binary identity, as well as takes into consideration the differential socio-caste status of trans people in the subcontinent, directing Indian central and state governments to make provisions for reservations in educational and employment opportunities for the trans community.”

Their work draws attention to the affirmative and liberating language of this judgment—a pivotal one in South Asian queer history which stands in contrast today with the recent Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act (2019), passed and celebrated by the nationalist government and its supporters in India.

Indrani Ashe, My Goddess gave birth to a Goddess, 2018, Digital video still. Image courtesy the artist.

Shubhra Prakash and Rajeev Prakash Khare, FONTWALA, 2021, Digital web project still. Image courtesy the artists.

The artists connected by this exhibition, are individually embedded within multiple charged political conversations, charting their own passages even while being geographically or culturally situated. As such, the exhibition creates an alternative map of practices—across geographies, identities and aesthetic dispositions. Many of these practices are rooted in the digital/virtual spaces, which become surfaces for the materialization of marginalized narratives—a home for placelessness.

Anisha Baid is an artist and writer from Kolkata, India, currently pursuing an MFA at the Carnegie Mellon University. Her practice and research involve an investigation of pervasive technologies through an examination of their design, diversity of use, and their relationship with ideas from science fiction. Her work attempts to poke at the flat-scapes of the computer screen to decode computer labour through the interface—a technological tool that has converted most spaces of work into image space. She is also invested in understanding digital image cultures through the lens of photography and works extensively with appropriated stock images and commercial imagery.

NOTES:

1. See Ammara Maqsood. The New Pakistani Middle Class. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017.

2. See Svetlana Boym. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001.