Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Love & Other Hurts

Tender threads of solace

my trousseau of Phulkari

longings, whims and fancies

bundle of bolis and galis

locked in my heart, love and other hurts.

A reluctant rishtah picture

for an unseen husband

shipped to England

migrant in the bedroom

locked in my heart, love and other hurts.

Silence of a cold life

empty house, late night shifts

garam bistar shared by six

hair short, unsparing hand

locked in my heart, love and other hurts.

The cooking, the cleaning

the foundries, the fears

the lashes, the loathing

deluge of tears, rivers of blood

locked in my heart, love and other hurts.

Broken mother, abusive home

lost childhood, a seam torn

in thousand sleeves cut

my escape stillborn

locked in my heart, love and other hurts.

I rose in rebellion

against father, brother, cousins

ready to murder for honour

I tried to kill myself

locked in my heart, love and other hurts.

The cost of dreaming

marrying a photo, honeymoon wife

a plastic plane at altar of faith

forever vilayat, forever desire

locked in my heart, love and other hurts.

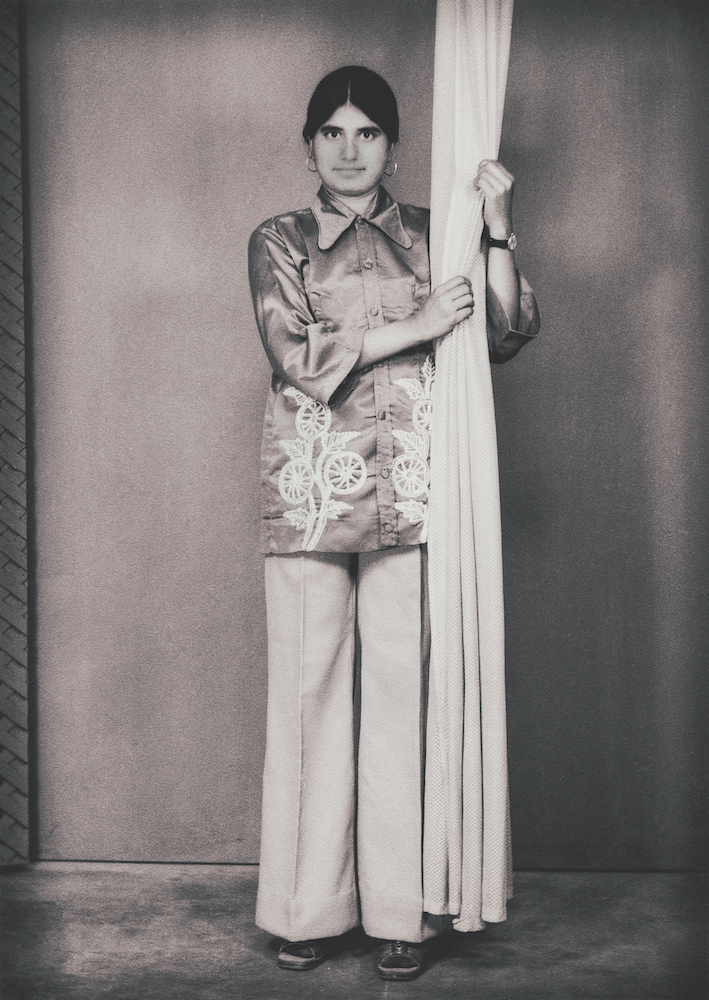

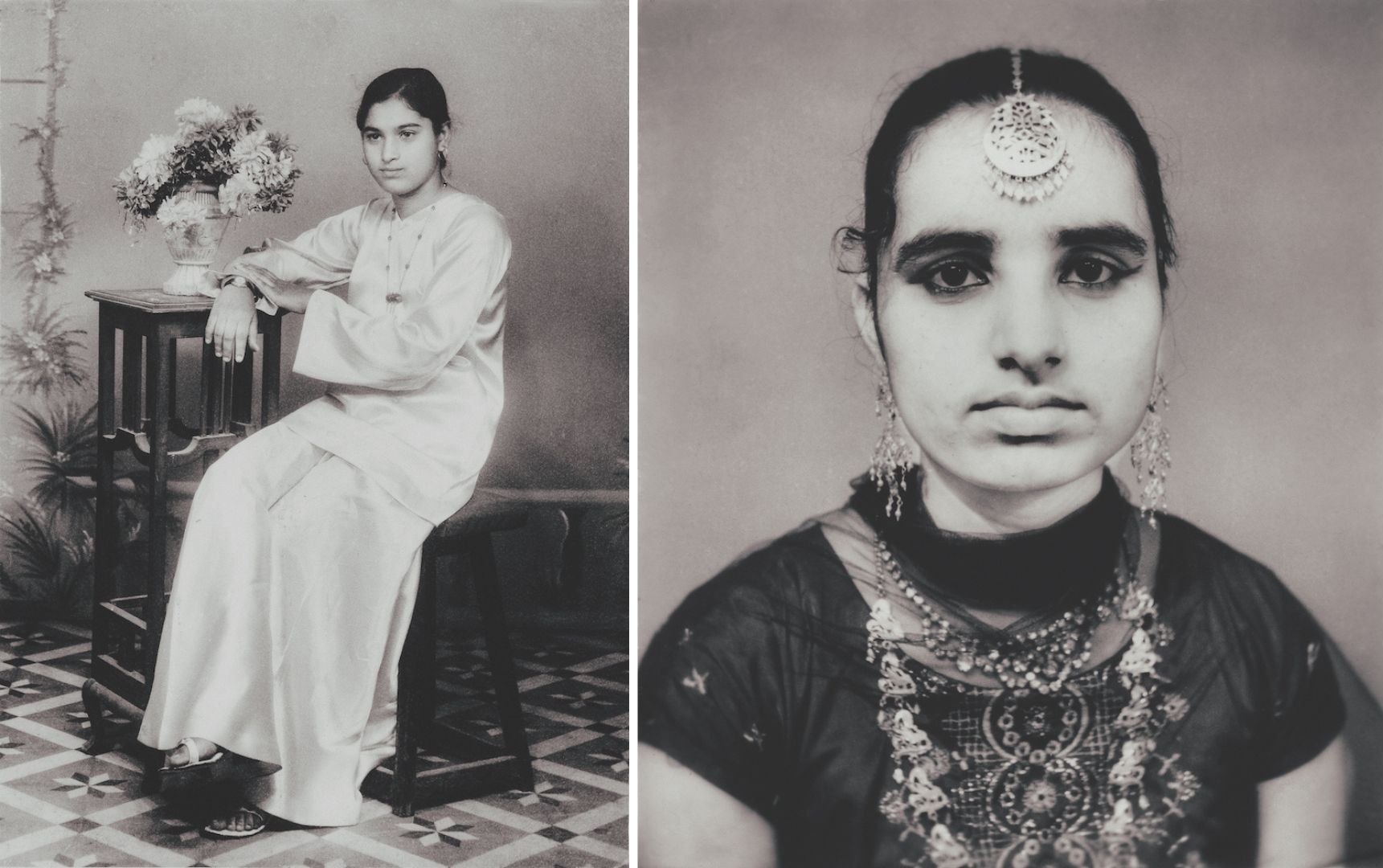

Love & Other Hurts attempts to paint a psychological map of the lives and experiences of British-Punjabi and Indian Punjabi women over the last seventy years. It draws upon personal accounts of love and longing, family bonds and cultural traditions to highlight their struggle to survive in often very challenging circumstances.

Love has always been a central theme in Punjabi folklore, with women turning to songs or bolis and other oral traditions to vocalize their experiences. My series stitches together all these threads to create a visual tapestry of their journey. In many ways, it mirrors the tradition of phulkari embroidery to represent the taana-baa-na (weaving) of life and journeys into the unknown.

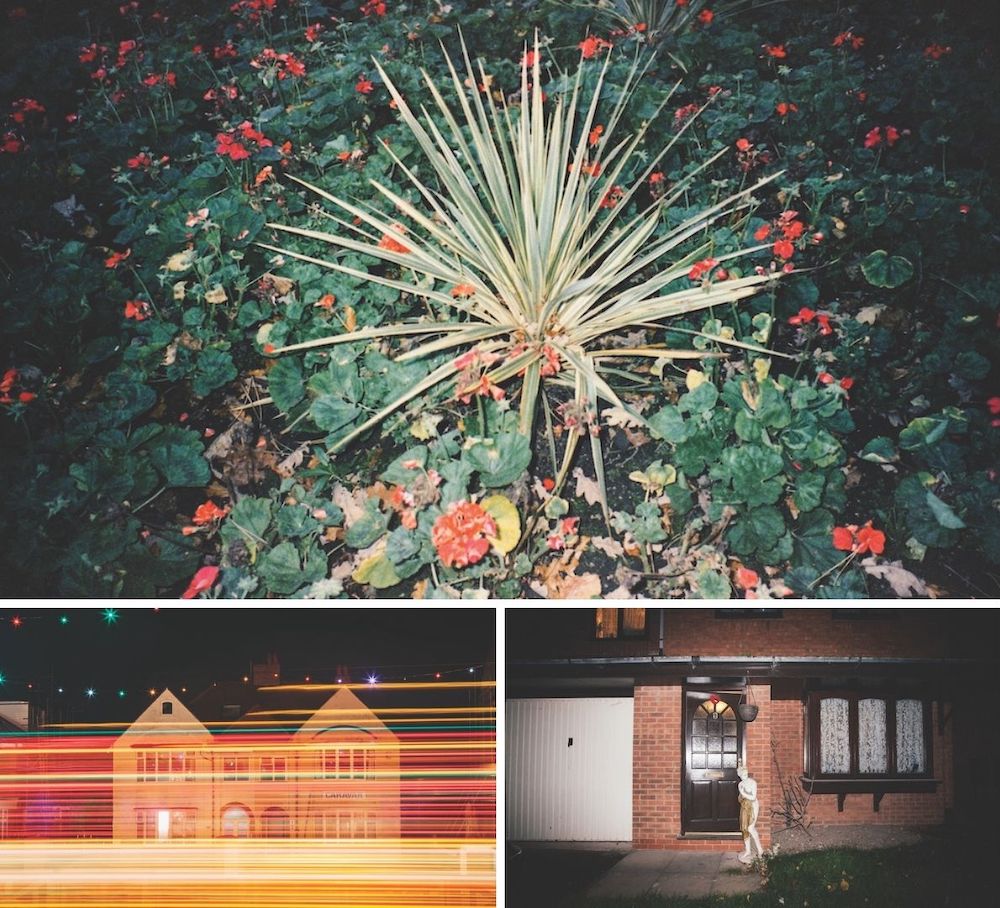

Historically, the migration of communities from rural Punjab to the West Midlands grew out of a demand for cheap labour in the aftermath of the Second World War. Immigration policies favoured workers from Britain’s former colonies. This led to an exodus of men from Punjab who were scalded by the trauma of Partition as well as political and economic instability. Strong community networks facilitated this process of immigration.

For the first generation of migrant women in the Black Country, their journey usually started with a “rishtah” photograph—a picture of the woman was sent to a prospective groom. A few families even sent their daughters without sharing the prerequisite rishtah picture. One woman recounted, “My father would say, ‘Maine apni beti ki numaish nahi lagani (I do not want to put my daughter on show).’ So, I first saw my husband on my wedding day. I accepted my father’s decision to send me wherever he saw fit.” Some women were married off at very young ages and waited for years to join their husbands in the United Kingdom. One woman recounts: “My fiancé used to call from the UK. But it was expensive. So, he started writing letters to me. He did so daily, making my father comment: ‘What does he write to you every day?’ But it was through this exchange that I came to know my husband.”

Most of the early migrants from Punjab in the 1950s and 1960s belonged to agrarian communities rooted in nineteenth-century feudalism and patriarchy. Women did not have any agency or the right to decide their future. Extended family bonds of baradari (kinship) and caste relations paved the way for women to find a footing and settle into their new lives. Brides—young and inexperienced—were sent to wed men they did not know and were compelled to live in an unfamiliar land. Their first impressions on arriving in the Black Country were often accompanied by a deep sense of alienation, loneliness, anxiety, fear and dislocation.

Everyday life during this period involved men working long shifts in foundries or factories, while the women were confined to their living quarters. Life was hard and finding work was not always easy. The language was also a barrier. Interaction with the local people was limited. Many Sikhs felt compelled to compromise their faith by cutting their hair and discarding their turbans so that they did not stand out. The anti-immigrant speech, “Rivers of Blood” by the Conservative Member of Parliament Enoch Powell in 1968, set the tone for the discrimination and segregation that guided public sentiment in those days.

Control over women and young people in general was considered essential to the community’s collective identity. For women to work outside the walls of the home was considered a “behzati” (dishonour). This, however, changed in the late 1970s and early 1980s with the closure of many of Britain’s manufacturing industries. Women were compelled by their families to supplement their husband’s meagre earnings by joining the workforce. Many of them took up sewing. A woman from Wolverhampton explained:

“I had to work very hard. Not only taking care of the cooking, cleaning and the children but also making ends meet by cutting thousands of sleeves and sewing them for up to four or five hours a day besides the housework. So that we could give our children an education and a better life.”

Growing up came with its share of cultural and generational conflicts for the children of this generation. Second-generation diaspora women had to submit to the wishes of their parents and were wed often very young. If they did not, they faced an uphill task,

“I did not go down the traditional route to find myself a partner. I tried online matrimonial dating websites, did not succeed and then the speed dating events came along. You paid twenty pounds, and you got to talk to fifteen boys… and by the end of the night, you could indicate if you wanted to meet someone. Gurdwaras also started preparing lists—an excel spreadsheet—of singletons with maternal/paternal surnames, age, height, job, qualification, etc. I tried them all before finding myself a husband.”

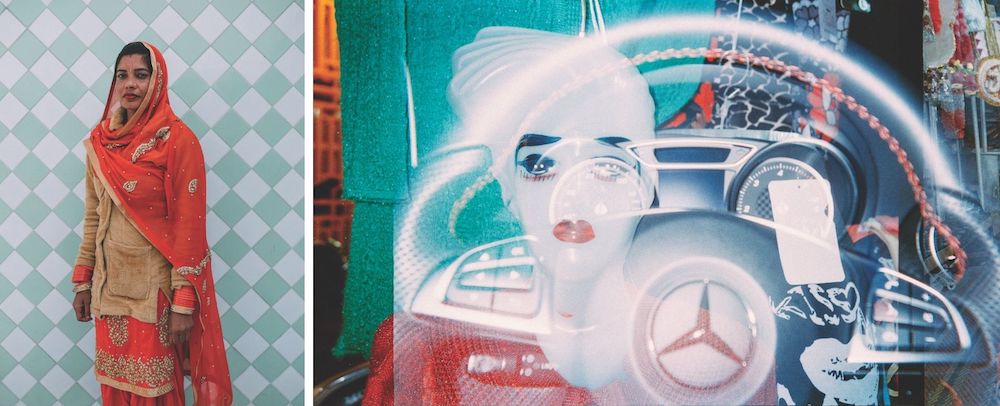

For the women who refused to submit to an arranged marriage, hard-earned freedom was loaded with symbolism. A forty-year-old woman with a university education and a stable job said that she saved up for a wedding that never took place, “When I turned forty, I used my marriage money to buy myself a fancy car. In my father’s generation, when the men did well for themselves, the first thing they did was to buy a car. I did the same.”

Rebelling against parents and the community came at a cost. One woman married to a person suffering from drug addiction not only faced physical abuse, but failed to convince her family that her husband needed medical help. Another woman attracted retribution from the community by daring to live with a man from a different faith, “They kept saying I am sold goods. They tried to kill me. My mother did nothing.” Yet another woman, deeply impacted by her father’s physical violence against her mother, turned to self-harm, “I tried to kill myself when I was seventeen with an overdose of tablets. I have been in and out of psychiatric hospitals.”

These accounts of trauma have never been talked about openly. Instead, Punjabi diaspora communities choose to project a happy face to the world and, in particular, to families and friends back home. Wealth and success camouflage inner hurts. This, in turn, fuels dreams of happy futures for Punjabis eager to emigrate to foreign lands. As one journalist working in the Jalandhar area explained, “Here, everyone is dreaming of vilayat (foreign land). You will find young girls willingly marrying a photograph, or a sword, or even the handkerchief of an emigrant in order to find a new life outside the country.”

Many of these marriages end in tragedy. Non-Resident Indian (NRI) men have been found marrying women from the Punjab under false pretenses, demanding dowry and celebrating their honeymoon only to leave without a trace. In the three years from 2014-17, as many as 20,000 women went through this experience. A sufficiently large enough number to wake up the government, it has reacted by warning that it would confiscate properties to put a halt to this malpractice.

The challenges of emigrating cannot be understated. Leaving home and getting used to a different culture poses many trials to one’s sense of identity, belonging and community. These challenges are compounded for women who are born into value systems that already impose restrictions on their lives. This is certainly true for many of the first and second-generation British-Punjabi women. For them, it is love and other hurts that define their stories.

***

The technique of multiple exposure has been used to interlace individual stories with literature, archives, family albums, personal letters, objects and other found material. The participation of the subjects in the image-making process defines this work. I had given analogue film to a handful of the women subjects to shoot. Over these, I photographed my impressions based on extensive interviews with them, often reshooting the films shot by British-Punjabi women back in Punjab. The element of chance while reshooting the analogue film plays on blurring the boundaries between personal and communal, time and location, as well as fact and fiction.

This series was first shown as part of the exhibition Girl Gaze: Journeys Through The Punjab & Black Country, UK curated by Iona Fergusson, under the Re-imagine India Project (2016) by the Arts Council England and the British Council and was supported by Creative Black Country and Multistory (UK).

All images from the series Love & Other Hurts, 2018.

Uzma Mohsin uses photography to unravel narratives of people, places and their histories. By looking at cross-cultural encounters and perceptions, her work tries to build a conversation around the idea of belonging. Her image-making process involves experimenting with abstraction and metaphoric expression. She has exhibited both in and outside of India—her recent exhibitions include Girl Gaze: Journeys Through the Punjab & the Black Country, UK; Blast Festival, West Bromwich UK (2019); Ellipsis: Between Word and Image, Jawahar Kala Kendra Jaipur (2019); Ephemeral: New Futures for Passing Images, Serendipity Arts Festival, Panjim (2018) and India/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art, FotoFest Biennial, Houston (2018). Her series ‘Songkeepers’ was featured in issue 243: ‘Looking Out/Looking in’ of Aperture magazine in 2021. She is also the recipient of the Alkazi Foundation Documentary Grant (2017). She was born in Aligarh and has graduated from the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, India.