Choti, Nairobi, Kenya, 2017, Digital photograph.

Nalini is a family portrait consisting of a series of photographs and objects brought together by Arpita Shah as she attempts to trace her maternal line back through time and place. The Sanskrit word for “lotus,” Nalini is also the name of Shah’s maternal grandmother. The lotus and other flowers—such as bougainvillea—are used throughout the series as symbolic motifs alluding to femininity as well as the cycle of life, death and rebirth.

Shah’s pastel infused photographs were made in Ahmedabad, Mahemdabad, Mumbai, Mombasa and Nairobi. The collection is enhanced by the inclusion of old black-and-white photographs that were discovered and excavated from her grandfather’s attic. She also uses objects such a sari, old passports and signage to enrich this story of family, time and migration. Western representations of India are often infused with loud, vibrant colours. By contrast, Shah’s pastel shades of pink and blue as well as the occasional greens and yellows are soft and faded. For Shah, they hold associations with the warm light of both India and Kenya. Shah’s family moved to Kenya from India in the late 1920s in order to establish Krishna Milk Depot in Nairobi. In an old photograph, Nalini can be seen as a young girl standing next to her little brother among a large group of workers and a cascade of silver milk urns. The family was forced to return to India due to the outbreak of the Second World War.

Once back in India, Nalini longed for Nairobi. The sense of displacement, as a key vector throughout the series, is palpable in one photograph in particular—of an ageing Nalini looking out over Ahmedabad from her family apartment. Shah herself was born in India but raised and educated between Saudi Arabia, England and Scotland. Together with her mother, she travelled to Kenya for the first time in order to research this project. They tried to locate the original site of the family dairy on Canal Road. However, as all the street names changed once Kenya gained freedom from British rule in 1963, the search—at first—was in vain. Then, through a chance meeting with someone whose own ancestors had purchased the land, they managed to eventually find the location. Shah took a fragment of a brick from the erstwhile dairy wall as proof of her successful quest, an object she displays within the series as a marker or trace. Images and objects thus form a sensory thread along with beads, strands of hair, close-ups of skin and flowers, etc. Together, they represent the currency of familial ties that generate a space in memory, so as to mitigate the disorienting effects of successive displacements.

At the same time, tactility and presence are central to the work. Shah’s portraits of her mother and grandmother are envisaged through evidentiary modes of representation—partially, or taken from angles that do not show their faces in entirety. She speaks of wanting the viewer to experience a sense of longing and distance, of reaching into her images in an attempt to touch and, perhaps, reshape memories; but in the end, being unable to access them completely. Shah also photographs still lifes intimately connected to her ancestors. This includes her great-grandmother’s passport, or a braid of grey hair now shorn from her grandmother’s head following a serious illness—both adorned lovingly with flowers. Photographs themselves become still lifes—held in the hand, encircled with petals or placed in the sands of Mombasa beach. Through these treasured objects, Shah makes manifest her own memories and attempts to create new memories of belonging.

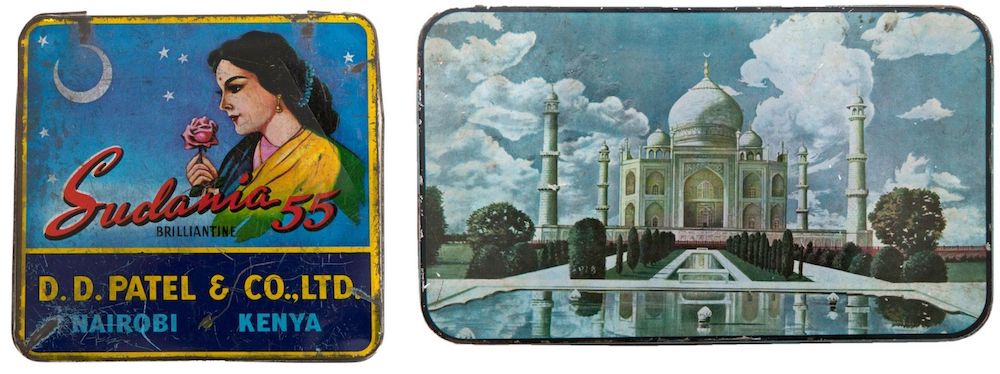

Left: Sudania Tin, Kenya, c.1935, Digital photograph. Right: Great-Grandfather’s Asoo Sweets Tin, India, c.1930s, Digital photograph.

Left: Canal Road, Nairobi, Kenya, 2017, Digital photograph. Right: Nalini in bloom, Ahmedabad, India, 2016, Digital photograph.

Left: Untitled, Ahmedabad, India, 2016, Medium format film. Right: Parimal Gardens, Ahmedabad, India, 2015, Medium format film.

Reshma, Ahmedabad, India, 2015, Medium format film.

Left: English Blue, Ahmedabad, India, 2015, Medium format film. Right: Nelumbo at Dusk, Ahmedabad, India, 2016, Digital photograph.

Left: Bombay, Mumbai, India, 2015, Digital photograph. Right: Untitled, Ahmedabad, India, 2016, Medium format film.

Nalini’s Hand, Ahmedabad, India, 2017, Digital photograph.

Mahemdabad, Mahemdabad, India, 2016, Medium format film.

Arpita Shah is a photographic artist based between Edinburgh and Eastbourne, UK. She works with photography and film, exploring the intersections of culture and identity. Shah spent the earlier part of her life living between India, Ireland and the Middle East before settling in the UK. This migratory experience is reflected in her practice, which often focuses on the notion of home, belonging and shifting cultural identities. Shah’s work tends to draw from Asian and Eastern mythology—using it both visually and conceptually—to explore issues of cultural displacement in the Asian diaspora.

Frank McElhinney is an artist from Scotland whose work focuses on themes of conflict, migration and nationhood. McElhinney studied Fine Art Photography at the Glasgow School of Art, graduating in 2014. He has a first degree in Medieval and Modern History from Glasgow University. He has exhibited in Scotland and internationally; with projects covering the Antonine Wall, the demand for Scottish Independence as well as migration from the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. His projects often look through a historical lens, but seek to address thoroughly contemporary issues.

Watch Arpita Shah talk about Nalini:

View this post on Instagram