Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Of Sandcastles between Sea and Sky

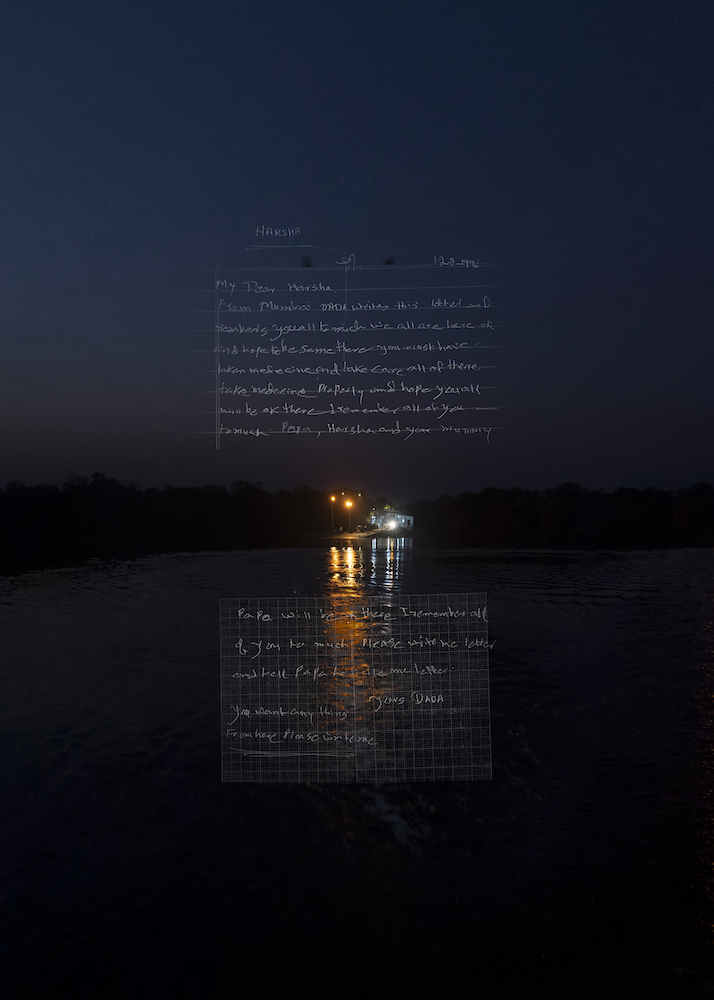

Untitled. “Dada’s last letter addressed to seven-year-old me after he moved to Mumbai post-retirement. The view is of a creek I visited in December 2020 searching for the address of his first home in Mumbai, which—for the lack of precise memory or material evidence of—I’m yet to find. He had begun declining into dementia during this time.” 2020, Digital collage.

The power of nostalgia lies inherently in loss—in the impossibility of returning to another time and place, or even an earlier version of oneself that remains tethered to the past. But what happens when the place to which one is attached is lost in a different way—catastrophically changed for those who continue to inhabit it? What if this place had always been only a mirage, flitting away as readily as it came into being? In how many ways can home be lost? In how many ways can home be found?

Generations of migration. All water, no ripples.

I don’t belong to Sindh, where my grandparents drew their first breaths and pictures of childhood—nostalgic sketches now tainted with a violent political past. Neither do I belong to Mumbai, where a small section of their then-displaced community came to rest, scattering across India like seeds in the wind. My departed don’t seek shelter in Jaisalmer either, where the oldest promises of home can be traced back to a mere scent, faded allegiances forgotten even by the dead.

Saltwater becomes lifeblood.

Westbound winds first brought my family and many other hopefuls to the then Trucial State of Dubai for trade, traceably over a century ago. Years later, the Partition and subsequent degradation of financial and emotional resources would make for my family’s final departure from Sindh to join the soon-to-be United Arab Emirates in building things anew. Decades later, a born-expat, I still ask, where do I belong?

If you cannot call the place you were born home, then where can you call home?

In this ongoing work, I have journeyed across four generations of emotional geographies in studying the people, places and objects around me. Driven by the need to understand how we arrived at the odd niche we inhabit in this cosmopolitan, yet insular, playground that is Dubai, I have immersed myself in whatever little remains in material and memory to piece together a clearer picture of the foundations we once stood firmly on. Even in the most recent liberal offerings of bureaucratic acceptance through longer-term residence permits or the seductive allure of citizenship, the fine print ensures access to only a select few born into immense privilege. If, then. Your merit measured in millions, the temporariness of belonging an unchanging undercurrent.

Oceans swell; maybe the tide washes over everything you’ve ever known to belong to, maybe it won’t… Now, rest.

In a world that asked of him to revel in the permanence of his temporariness, how did he find the will to build a life, suspended between sea and sky? This work is for my late grandfather, Haridas Maghanmal Pandav—Dada, who despite involuntarily and voluntarily spending almost equal thirds of his life across colonial Sindh, Dubai and postcolonial Mumbai, always remembered his way back home.

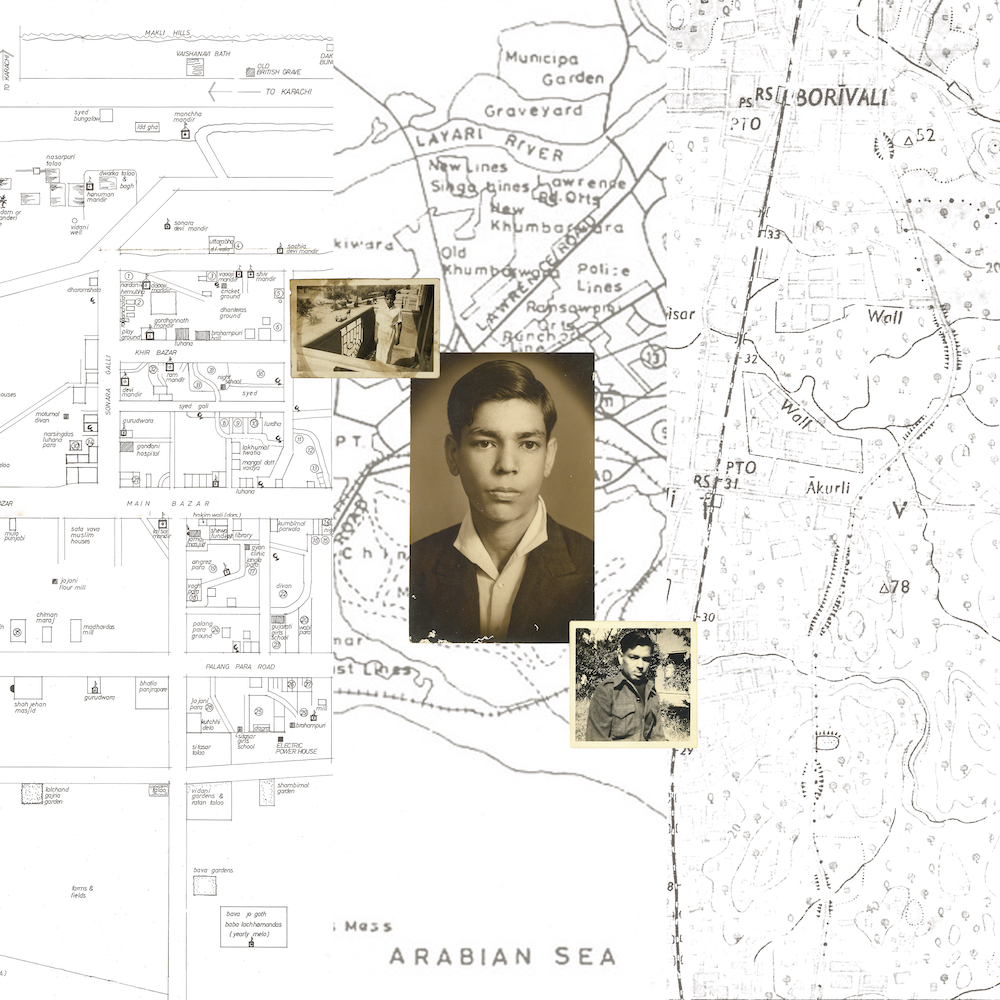

Dada, Growing Up. (Top to bottom:) Thatta, Karachi, and Mumbai, between 1930 and 1947. “Each place was home to its own secret personal milestones. Fractured in space and time, each became just as ungraspable as the last. Colonial influences remained omnipresent, even following him into his future in the Trucial States. The map on the left is of Thatta, hand-drawn from memory by one of my grandmother’s uncles—a manufactured souvenir to retain some semblance of community. The other two were found in public archives.” Digital collage.

Dada, Growing Older. “A few rare and incredibly precious images taken of Dada (seen here with my father) in the Trucial States of Dubai and Sharjah between 1964 and 1967. The top right image shows what is possibly the area of Souq-Al-Baniyani (now the Bur Dubai creek, or more recently the Al Seef project) named after the Baniya—a dominant-caste merchant trader community from India. The background is an aerial image of the region taken roughly within the same era, found in public archives.” Digital collage.

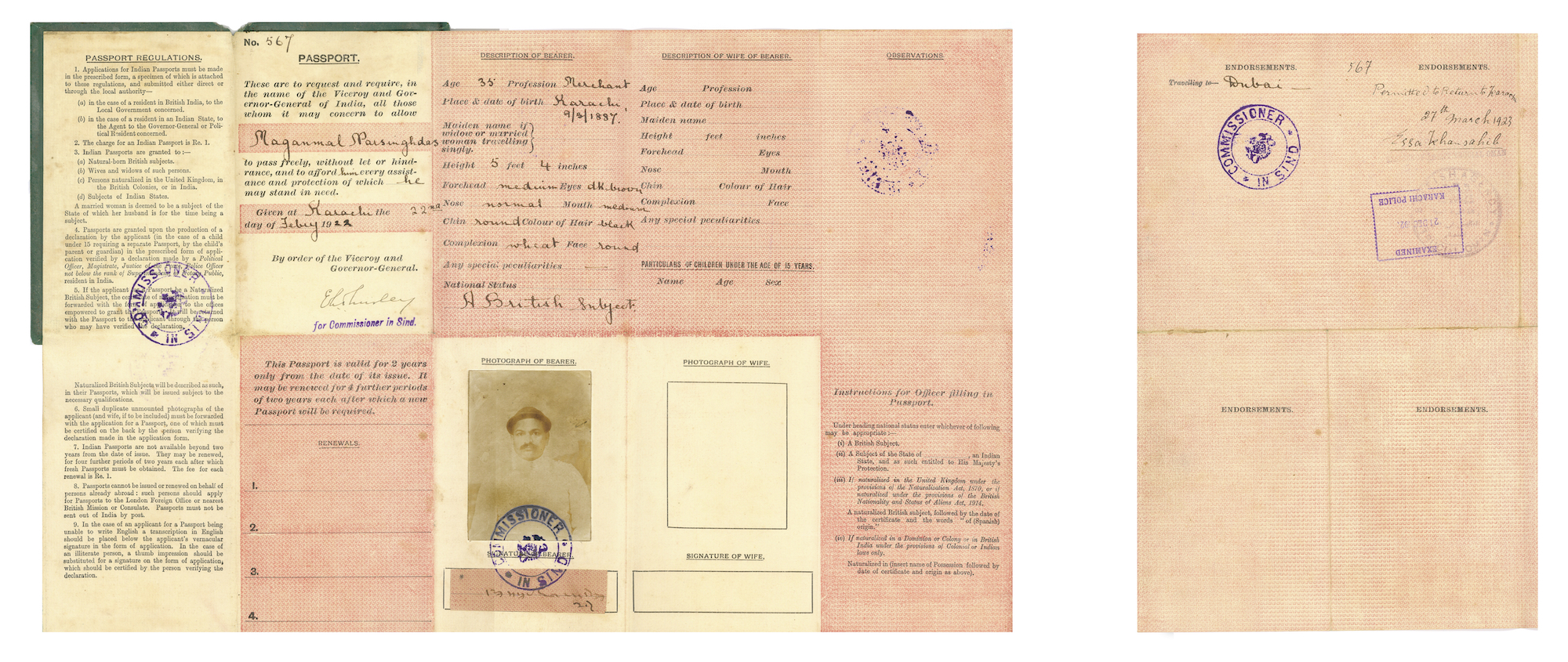

Great-grandfather’s passport.

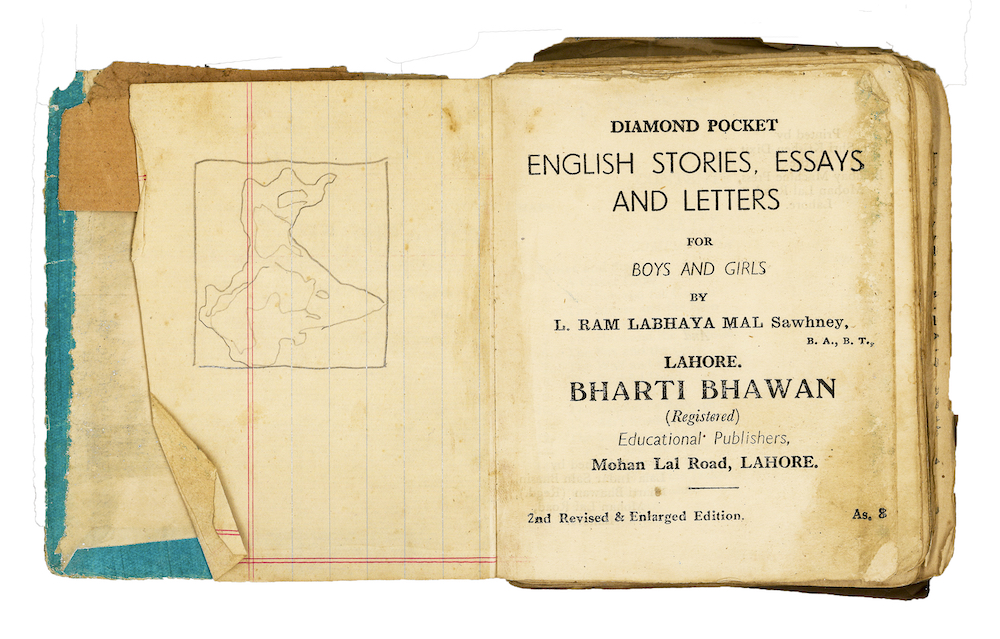

Dada’s English-medium textbook from the early 1940s in Karachi, with a doodle of India. By the time he was sixteen-years-old, he had formally studied—and was fluent in—at least four distinct scripts. Digital photograph.

Childhoods under Dubai Skies (Father and I). “The first time Dada met his son, my father was eight-months-old. My grandmother traveled to the Trucial States with all her children to stay there for just under two years. There were still no accessible formal schools for ‘expat’ children in the region at the time, so settling there as a family was not yet an option. The picture of my father here is from the end of this trip, when he was about two-years-old. The next time he would see his father was two-and-a-half-years later, over another similar extended visit. By the time I was born in 1989, the country had developed significantly and whole families were increasingly able to settle there. Dada was still employed in Dubai when the photo of me here was taken in 1990. He was forced to leave after his retirement due to visa restrictions and financial constraints, only a few years later. Separation, somehow, transcended generations.” Dubai, UAE, Images from 1965-66 and 1990, Digital collage.

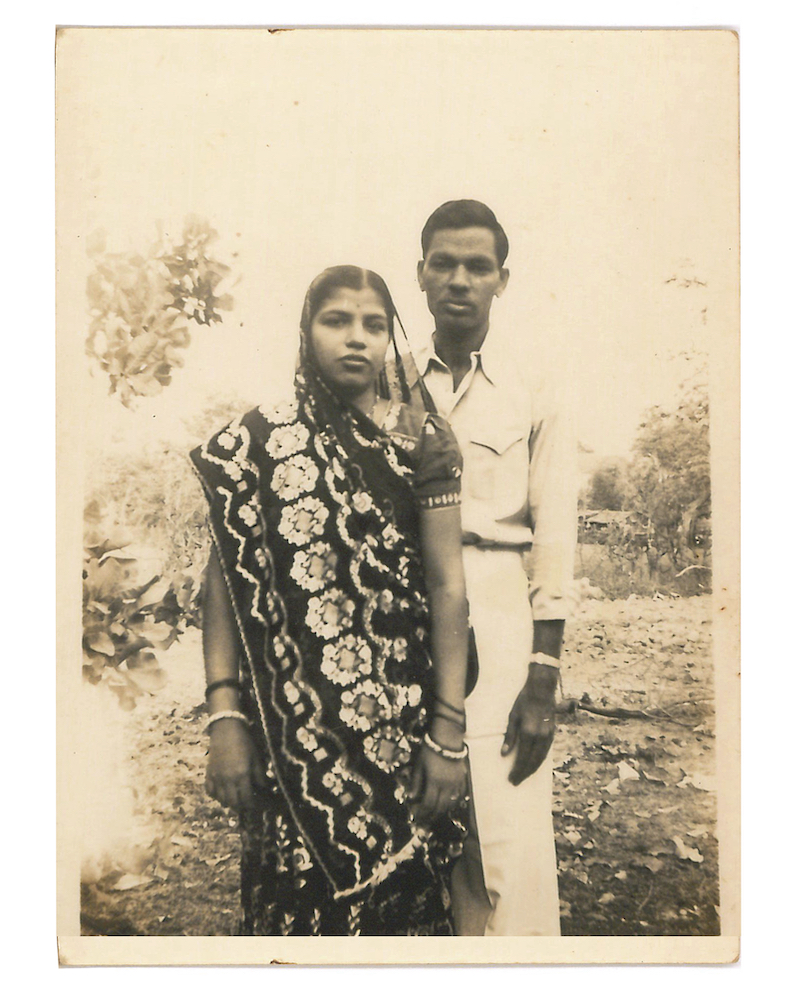

Mumma and Dada in Bombay, India. “Photographed in 1953, Mumma, seen here in her early twenties, was pregnant with their first child. She married Dada in 1948, but due to the financial and emotional shock of Partition, the family was not able to hire a photographer or host a proper wedding. This was the first photo taken of them together since their marriage, leaving with her no memorabilia of their wedding ceremony—something that troubles her to this day. Two years after this photograph, post-Partition, Dada left for the Trucial State of Dubai to look for better career opportunities. She followed Dada to Dubai when their first-born turned seven. They were together when he passed away at home in Mumbai, in the summer of 2011.” Digital scan.

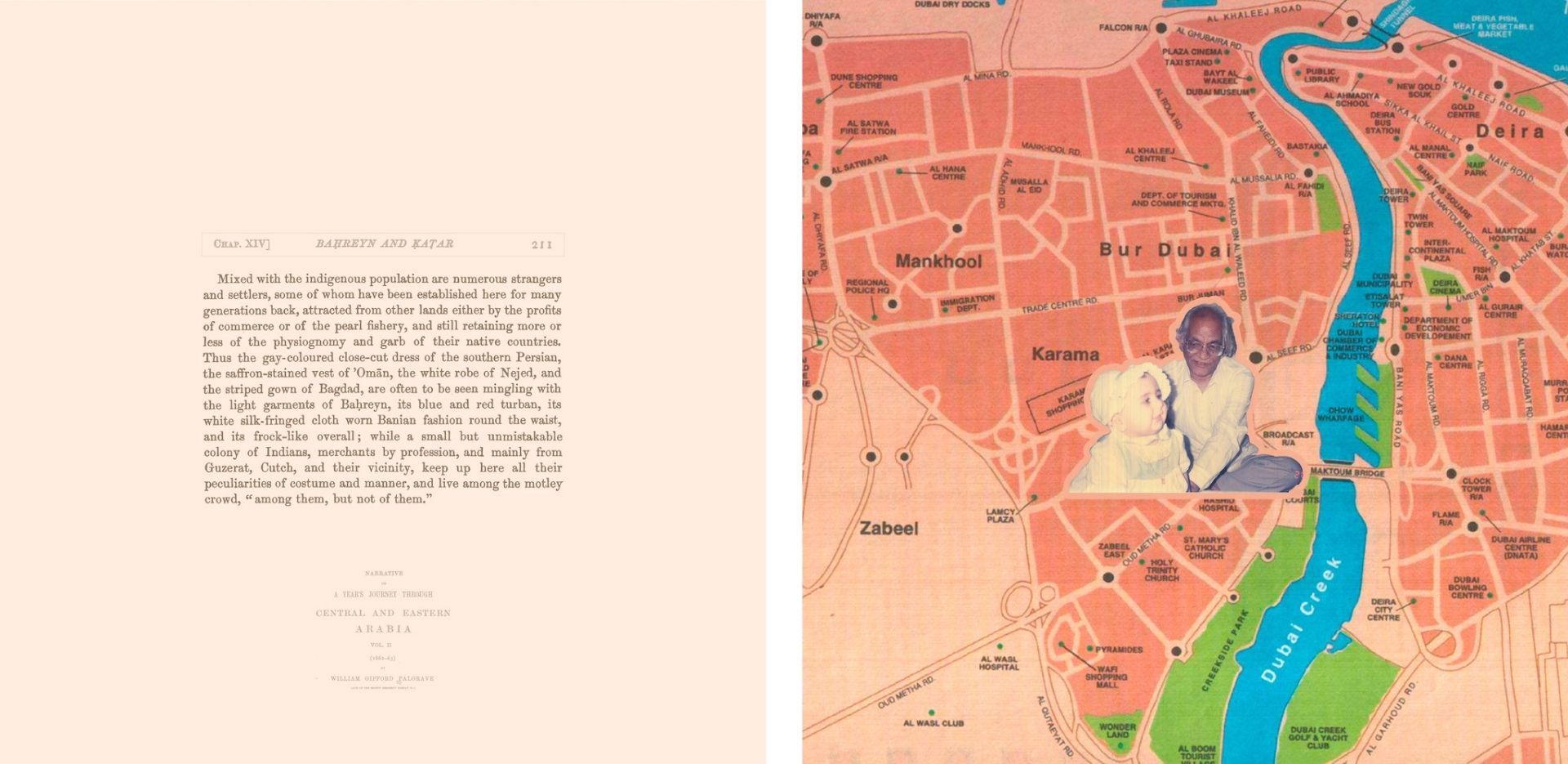

Left: Among Them, But Not Of Them. Excerpt from A Journey Through Arabia, Palgrave (1862), Digital photograph. Right: Home with Dada. “In the last few of his forty-odd years spent living in Dubai, Dada and I would walk to the creek and along the water’s edge to feed the fish every evening. For various reasons pertaining to health, finances and unfriendly bureaucratic policies post employment, it isn’t always possible for senior citizens to retire in the country. Nor is it feasible to travel back and forth every six months, as it is still demanded by the law to keep a longer-term residence visa valid. Our walks here are my last memories of the time spent with my grandfather as a child in Dubai, before we were separated by his retirement. He continued to send me a card on every birthday. I continued to visit him every summer I could, until college.” Image from 1990, 2021, Digital collage, scan.

Top Left: Untitled, 2020, Digital collage. Bottom Left: Bloodfire, Dubai, UAE, 2017, Digital photograph. Right: Moonrise Kingdom, Dubai, UAE, 2020, Digital photograph.

Harsha Pandav was born and raised as a fourth-generation expat in Dubai, UAE and having recently moved to India—the country of her citizenship and ethnicity—in December 2020, Harsha has long been curious about narratives centred around home, identity, childhood, race and the politics of belonging. She is currently engrossed in exploring the many ways in which artistic interventions using non-traditional media can create and dismantle narrative structures, both political and personal. In conjunction with this, she is birthing an initiative called Brown Girls Diving, to promote visibility for women from the majority world in diving, conservation and the marine sciences.