Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Samba Shiva

To Chittiabhaiyi Patchineelam, from Rio de Janeiro, 28 July 1978.

In 1967, having completed his degrees in Geology, Sambasiva Rao Patchineelam left his town of Rajahmundry in Andhra Pradesh to pursue his higher studies in Europe. At the time, he was unaware that this would be the beginning of a journey that would lead him to Brazil, where he would get tenure as a Professor, meet his future wife and build a family with three children. In the years of his emigration out of India, after receiving a camera as a gift from a friend in 1972, Sambasiva began recording his life in images, building a photographic archive spanning three decades. Many of the images he made were on visits back home, of his family and friends in Rajahmundry—some made to pose with saris as backdrops and others candidly photographed with gifts, like a red Olivetti typewriter, that he brought back with him. In his collection, these personal, familial images sit alongside some unusual suspects—images of rock formations and soil samples, to name a few—that bring his working life as a geologist into focus. Even others revealed his itinerant journey across Europe and South America—aboard a research cruise ship from Germany to Hawaii, the landscapes of stops along the way like the Panama Canal or the Galapagos Islands, and eventually images of life in Brazil.

In 2005, Sambasiva’s son Vijai, an artist himself, began to digitize a few thousand slides and some printed photographs, for the fear of losing his father’s archive to the humidity of the Rio weather. This was the beginning of the process that crystallized this archive into the book “Samba Shiva: The Photographs of Sambasiva Rao Patchineelam,” which was published by the Brazilian cultural space Instituto Moreira Salles in 2017. In the book, Sambasiva, a scientist by profession, assumed the role of the artist and author of the work, and his son Vijai, an artist, became the editor. Vijai terms it as editing “through memory,” irreverent to the actual chronology of his father’s life. He sees the book as the “reconstruction of an enlarged transcultural identity,” one which showcases a migratory pattern that is not often identified with the Indian diaspora. His own identity is shaped by this. As the son of a Brazilian mother and Indian father, raised in a country where migration from India was not in constant waves (like that to North America), he felt that, with no other option, assimilation was faster into the local culture.

The title, Samba Shiva—a nod to the amalgamation of the Brazilian and Indian identities that inform the book—embodies its essence. The making of the book gave him, as the son, an insight not only into his father’s life before him, but also his Indian family and heritage. This is not just a record of a man’s unusual journey halfway across the world where he built a home and a life, but also a means for a son to understand his father, and eventually himself.

Tanvi Mishra: Migration from India to North America, UK and Western Europe is more commonly known. Brazil seems like such an unlikely place in the 1970s to immigrate or even travel to from India…

Sambasiva Rao Patchineelam: I am an outlier. Somehow I landed in Europe at the age of twenty-four-years and stayed there for about twelve years. At thirty-six I moved here; I married a Brazilian woman. I had a family with three children, but unfortunately my wife passed away. I left first for Europe, staying in Austria for two years, where I received some scholarships from the Austrian Government and UNESCO. Then I moved to Germany with the aim of doing a PhD.

TM: Do you remember what propelled you one day to leave for this foreign land?

SRP: It was a courageous step. At that time, things were not so easy as they are today and flights were very few. I flew from Visakhapatnam to Hyderabad first. From there, I went to Bombay, and then further on to Beirut. From Beirut, I took a flight to Geneva, and then finally to Vienna. It was a long way, it took almost two to three days. My family was worried about me.

TM: When you finally made it to Europe, you then made your way to South America. How did this unlikely trajectory take place?

SRP: I was in Europe for twelve years, first studying and then working as a researcher. In 1979, I went to the city of Salvador in Brazil. I was invited as a Visiting Professor at the Federal University of Bahia. I wanted to just see the country—the customs, their traditions, their culture. There, I met my wife, as she was also at the same university that I was visiting. We met during an excursion. We were both geologists, and she helped me a lot in a strange, new country, especially since I did not know the language.

Actually, I wanted to go back to India, but things were not that good. When I finished my PhD in 1975, I approached the Vice Chancellor of the Jawaharlal Nehru Technical University in Hyderabad and shared my intent of coming back to my home country. He said that the University was unable to arrange a job for me there, and asked me to wait. I thought that without a job, it was going to be difficult to support myself financially. So, I went back to Germany where I already had a job in the university.

Charles Darwin Research Station, Galapagos Islands, Ecuador, 1978, 35mm slide film.

Untitled, Hawaii, USA, 1978, 35mm slide film.

I took a scientific cruise in 1978, I went all the way to Honolulu in Hawaii. On my way back, during a stop over in Brazil, I wanted to meet some friends who were already working there at the time. So, I came to Rio where I was taken, by one of my friends, to his Geology department at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. There was a lack of PhD scholars there at the time. I had a PhD along with a lot of research experience, cruise experience, etc., so they offered me a job immediately. However, after a week in Rio, I left for Belem in the north-east of Brazil, and then to Salvador. I received another job proposal there, which I decided to take, and I began my journey in Brazil. At that time, I did not know much about Brazilian culture. But I saw that the vegetation was very similar to India—you get all the fruits, whatever you buy in India, even Sitafal (Custard Apple) every day. I was very excited to see this. Also, the regime was very easy-going, not rigid like Germany. So I thought, why not take a chance for one or two years to become a Visiting Professor. I came to Brazil not knowing that it would become my destination for life!

TM: You have worked as a scientist your whole life, not as an artist per se. How did the idea of a photobook come about?

SRP: Well, my art emerged because of my son. I had never thought of doing all these things, but he put this idea into my mind. During the presentation of this book, I said to the audience, I am not Professor Sambasiva anymore, I am the father of Vijai.

I feel great. I have a wonderful son with the artistic view. My photography is from feeling; but he is coming from artistic knowledge—that is the difference. I feel very, very proud of him.

I practised photography as a hobby. I used to travel a lot in Europe. When I was a student, I explored France. I have even been to Greece six or seven times. Once, when I was visiting Canada, I met one of my friends from my student days in Andhra. He gifted me a camera, which was not easy to buy at that time. I had given that friend a gift earlier, a radio that was able to receive worldwide stations—manufactured by the German company Grundig. I bought a radio set for him so that he could tune in on Indian news. As an act of courtesy, he got this camera for me in exchange.

Vijai Patchineelam: But the first camera was stolen in Rio—the film camera. This was in 1990s. And then the second camera, which was also a film camera, we (my siblings and I) bought in the early 2000s. I think it was a Pentax. We bought it in Rio, for a trip to India we did together in 2008. He forgot this camera in the back of a taxi in Malabar Hills in Mumbai. And then we bought a digital camera…

SRP: So, somebody always gave me a camera to photograph…

When I was a student at Andhra University, we used to have a small group, where we used to exchange ideas. We had a small darkroom for developing film, printing, etc. But as students, we did not have any money. At that time, we were a just group of friends who used to put some money together and do these things. Whenever by chance, somebody had a camera, someone used to buy film and we used to take photos. I took my first photo in 1964 or thereabouts, before I had finished my Master’s Degree.

TM : Vijai, I wanted to get a sense of why you decided to make this into a book.

VP: The initial idea actually came from the Delhi-based writer, Hemant Sareen, in around 2013. I was scanning the slides, as they were getting fungus due to the humidity in Rio. I would send Hemant a few frames from time to time. He told me that they had historical relevance given the region, time and access to photographic equipment. When Hemant first told me that these photographs were not only technically very good but have an added value, I thought that maybe I should try to think of this not only as a photo album or collection of our family, but something that could contribute to a larger discussion.

I wanted to keep the authorship under my father’s name. But, in the first few attempts at trying to edit this book, I realized that to edit the book with just photographs from India, based on this argument, would not be enough. So I opened up the archive and included photos from Brazil, and also from my father’s professional life. Having talked about it with my father and Hemant, we started thinking about the idea of diaspora through my father’s unusual trajectory.

SRP: He had an artistic point of view, while I have a feeling for the photo. He looks at it with a different angle, not like me. After seeing the selection, I was trying to analyse why he had chosen these. For example, the Galapagos photograph, where the man is pointing his finger at a turtle—the exciting thing was that I had not seen a photo like it even in National Geographic, which I had subscribed to for close to thirty years, since my days as a doctoral student.

When I was a student in Heidelberg doing my PhD, I used to live with German friends. We used to get together on Fridays to do photo projections. In those days, printing a photo was expensive. But, if you took a slide, you could project it for the audience to show that you have been to this place or that place. So, this was cheaper, and we had wonderful get-together parties during our student life.

Since these are slides, they were positives. So I never bothered about taking the scans and getting them printed. I have so many—hundreds or thousands of slides. For the publication, he picked up only the good slides, not the ones with fungus.

TM: So, you are actually happy with your editor.

SRP: Yes, I am really proud of him. Now, because of him, you came to know me.

VP: Like my father said, a lot of these photographs were not made into prints. There were a few that I found later at an uncle’s house in the Rajahmundry. A lot of the family members were seeing these photographs for the first time. So, that was quite a nice experience for the younger generation—to see their grandfathers and uncles.

(To Sambasiva) In Andhra, when you were in the university, you were developing small black-and-white prints. Right?

SRP: Yes. Whenever we used to go for the field survey—as geologists, for field work—the students used to develop their own film. But the equipment at the time was very low quality.

VP: That is also a part of what I tried to show in the book—the two types of uses of photography. Towards the end of the book, there are some photos that he took of the mangroves, the soil, PVC pipes, transparencies, etc. So that was where photography was more like a tool, compared to the other, more personal images.

SRP: My profession took me to photography.

TM: You sometimes joke and say, “I am from Germany” and at other times you say that you closely identify with Brazil. In your mind, where do you belong?

SRP: If I had come directly to Brazil from India, I would have said that I am from India. However, Germany became an intermediate stage for me. So, somehow, I have become a bastard between two cultures. For me, Indian culture and Brazilian culture are very close but German culture is different.

TM: Vijai, you were born in Brazil. Has the book changed anything about your relationship with India?

VP: I grew up in Brazil, so India—for a long time—was very far. I do not know a lot of the cultural symbols. I am learning slowly but the more I go to India and experience it, talk to friends, read, watch films, etc., the more I learn.

Before the book, I was already going to India quite frequently. I started going more often as an adult. From 2006 and up until now, I would go every other year. And I got to know more of that part of my family as well. India is a very difficult country to get a good grasp on, it is very complex. The family dynamics were also very difficult to understand—we are such a big family, my father had left when he was quite young, and his parents also passed away early. So it is a process of constantly acquiring more knowledge and meeting more people. Now that I have been going for some time, we have shared enough moments to start developing a sort of relationship or closeness.

The book was also, in a way, this effort of trying to understand a little bit more about the family. My aunt even helped me with the index. There was a lot of work that we could not do by ourselves, since my father had forgotten some things. My younger cousin helped with translations, since my aunt does not speak English very well. So that was quite nice. And then later on, they also helped to distribute the book among the family members.

SRP: When my cousin came from the USA a couple of years ago, I gifted him my book and I sent one copy for his sister who is also in the USA. She had also left India at the same time that I left. And when she saw the book, she started recollecting, “Oh, look at this! I know these people! I lived with them, I lived here in this place…” So it was triggering that coming back (of memory) that allowed for further connections to be built.

TM: In this experience of both of you working on this book together, what has been its impact on the relationship of father and son?

SRP: Well, there is a lot, because he is carrying forward my thoughts.

VP: It was different to bring my father into, let us say, my professional life and also my professional circle. I think we were able to speak to each other a little bit differently then, because he was in my field of expertise. Before this process, my father always came to the exhibitions, but he would come only during celebratory moments. Now he is involved in the process of working or making the book. I got to know more details about his professional life, of when he was younger. We talked about things that maybe otherwise would have taken longer for us to talk about if we were just together, because now we had a purpose.

And then later on, with the book going to India, I think for me it has become that—to use the book as a way to establish a sort of dialogue with/in India.

Padma, Rajahmundry, India, 1977, 35mm slide film.

Saila, Sarada, Vani, Srinu, Raju, Poornam, Sanyasi Rao, Suryam and Sri Hari Rao, Godavari River, India, 1977, 35mm slide film.

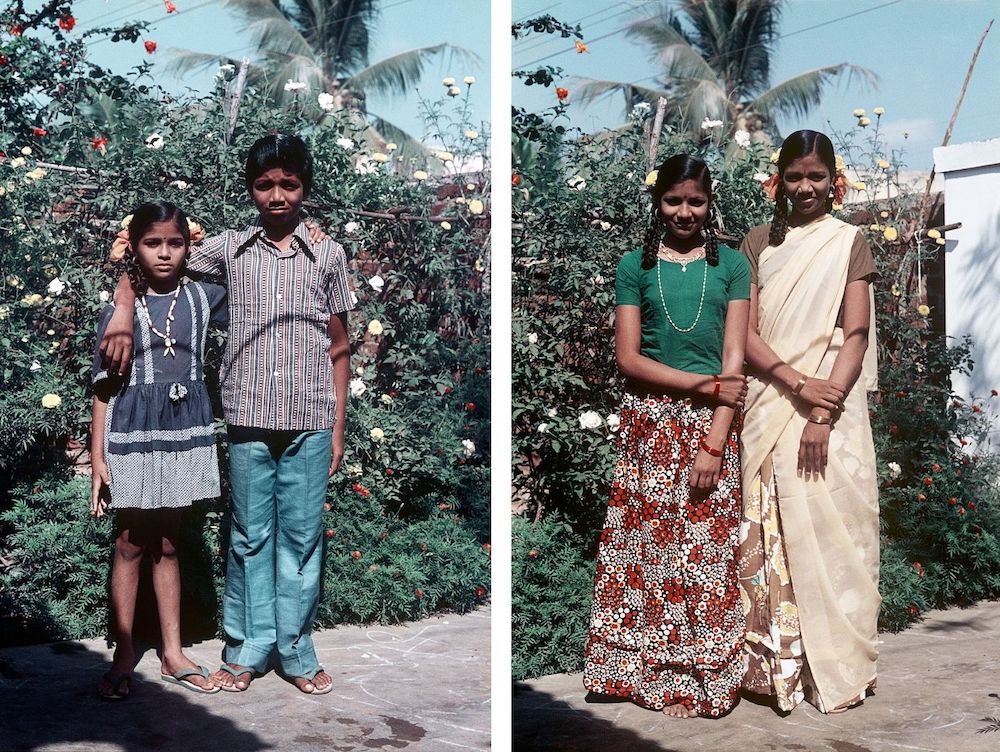

Left: Baby and Srinu, Kakinada, India, 1977, 35mm slide film. Right: Venkateswari and Prabavathi, Kakinada, India, 1977, 35mm slide film.

Left: Untitled, Hawaii, USA, 1978, 35mm slide film. Right: Usha, Eluru, India, 1977, 35mm slide film.

Sai Prasad, Kakinada, India, 1977, 35mm slide film.

Sri Devi and friends, Kakinada, India, 1977, 35mm slide film.

Left: Kamala, Kakinada, India, 1977, 35mm slide film. Right: Krishna Veni. Kakinada, India. 1977, 35mm slide film.

Untitled, USA, 1976, 35mm slide film.

Left: Laboratory, Research Vessel Sonne, 1978, 35mm slide film. Right: Sri Hari Rao and Manikya Das, Tatipudi Reservoir, India, 1977, 35mm slide film.

Left: Untitled, Hawaii, USA, 1978, 35mm slide film. Right: Pelourinho, Salvador, Brazil, 1980, 35mm slide film.

Ravi, Salvador, Brazil, 1981, 35mm slide film.

Sambasiva Rao Patchineelam was born in Rajahmundry, a small town in Andhra Pradesh. He graduated in Geology from the Andhra University in 1966 and then moved to Europe in 1967 to continue his studies. At the age of twenty-four, he went to Austria, where he did two post-graduate courses between 1967-69. He then went to Germany, where he received his Master’s Degree in Mineralogy—Technische Hochschule Darmstadt in 1971. He subsequently received his PhD in 1975. After four years of working as an Associate Researcher at Heidelberg, he moved to Brazil. He went first to Salvador, as a Visiting Professor at the Federal University of Bahia. Here, he married Soraya Maia Patchineelam and also saw the birth of his first son, Ravi, and daughter, Satya. In 1981, their family shifted to Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, where his second son, Vijai, was born. As a Professor at the Fluminense Federal University, he supervised numerous Master’s Theses and doctoral degrees until his retirement in 2013.

Vijai Patchineelam’s artistic practice focuses on dialogue between the artist and the art institutions. Placing the role of the artist as a worker in the foreground, Vijai’s research-driven artistic practice experiments with and argues for a more permanent role for artists—one in which artists become a constitutive part of the inner workings of art institutions. This displacement of roles is part of a larger trajectory that he follows in his PhD research at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, “The Artist Job Description: A Practice Led Artistic Research for the Employment of the Artist, as an Artist, Inside the Art Institution.