Ali Buc’s grave, The words “Indian Hawker” are inscribed upon his tombstone. Dunkeld cemetery, Victoria, Australia, 2020, Digital photograph.

Cradled in Kalkadoon country, Fotth Deen (d. 1935) rests today at a cemetery in Mount Isa in North West Queensland, Australia. With Asian people voyaging to Aboriginal lands long before British invasion, the traces of many Indian Ocean travellers remain scattered across the lands we today know as Australia. Telia is a work that offers glimpses into a chapter in this larger tale, recounting the stories of traders who came to be known as the “hawkers” from the late nineteenth-century. Arriving to the Australian colonies in 1890, Deen spent a lifetime navigating one of the most racist eras of Australian border drawing. In Jalandhar, “Telia” was the name given to “Australia” by the family Deen raised with his wife, Umri Bibi. However, precisely as Deen travelled back and forth across the Indian Ocean, pieces of legislation known as the “White Australia Policy” were enacted—controlling the entry, employment and movement of non-white peoples. Yet, as the tree drawn by their great-granddaughter, Mussarat Nisha Deen, shows, at the margins of White Australia, there flourished a family spanning the Indian Ocean.

In Telia, artist Yask Desai works closely with families, such as Deen’s, to invite audiences to view histories of South Asian travellers through a multivalent lens. The strength of the work lies in its juxtaposition of racist images of South Asians from white perspectives—that continue to view them as perpetual strangers—alongside personal and intimate archives created by the descendants of the hawkers in domestic, familial and sacred spaces. In placing these perspectives side by side, while moving between the past and present, Desai’s work refuses to relegate Australian racism to some distant past that has been superseded by a plural present—the thrust of much history writing today that tries to fold these colonized peoples from British India into stories of Western nation-building. Rather Telia invites the audience to inhabit the condition that black historian W. E. B. Du Bois described in 1903 as “double vision”: “This double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”¹

The result is a layered work that invites multiple viewings. While one strand of the work bears witness to the intergenerational white Australian racism spanning over a century, another tale Telia narrates is that of South Asian intergenerational continuity and oceanic connectivity that stands at stark odds with the borders that the Australia nation is infamous for. Viewed from yet another angle, the lone yet majestic tree that continues to stand in Jalandhar in Punjab, India in 2020, hints at the resilience of the Muslim and Sikh families who today navigate Modi’s India. With many hawkers treating Australia as part of a string of trading stops connecting Asian, African, European, Caribbean and North American ports; the view from within a mosque in Rotherham on the other hand, tells a story of South Asians’ survival at ground zero—where the violent ideologies of religious partition and racist border drawing originated—Britain. With centuries of European imperialism across the Indian Ocean world leaving a jigsaw of nation-states in its aftermath, Desai invites audiences to imagine another geography that is not partitioned along racial, ethnic and religious lines. Telia existed then and exists now, alongside and despite the nation-states of Australia, India, Pakistan and Britain.

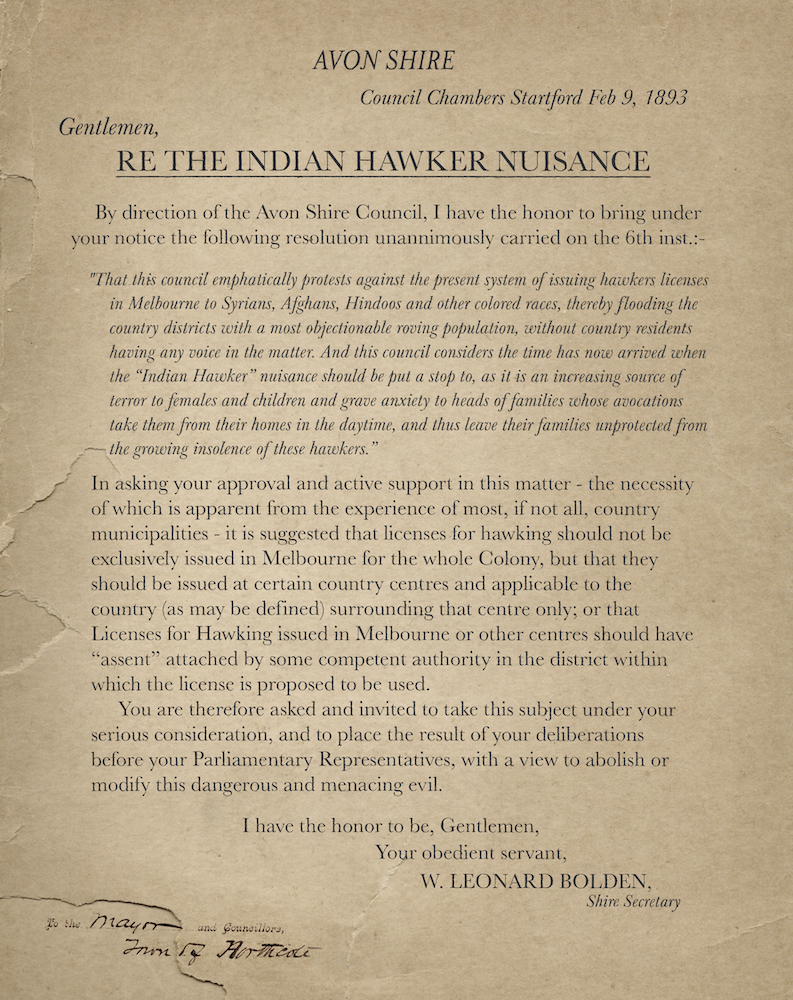

Petition, early twentieth-century. A petition from the Avon Shire Council to the Victorian Parliament in Australia seeking a decentralization of the licensing process for hawkers as a means to combat a perceived “Indian hawker nuisance.” Stratford, Australia, 1893, Digital scan.

Unknown Photographer, Fazal Deen and unknown compatriot with Fazal’s Chevrolet truck bearing his father’s name. Both Fazal and his father, Fotth, used this truck for hawking goods in rural Queensland. The truck was purchased by Fotth Deen in 1916 and was chain driven. It allowed him to vastly expand both his hawking and other business activities. Brisbane, Australia, c. 1930, Digital scan. Original photograph courtesy Deen family.

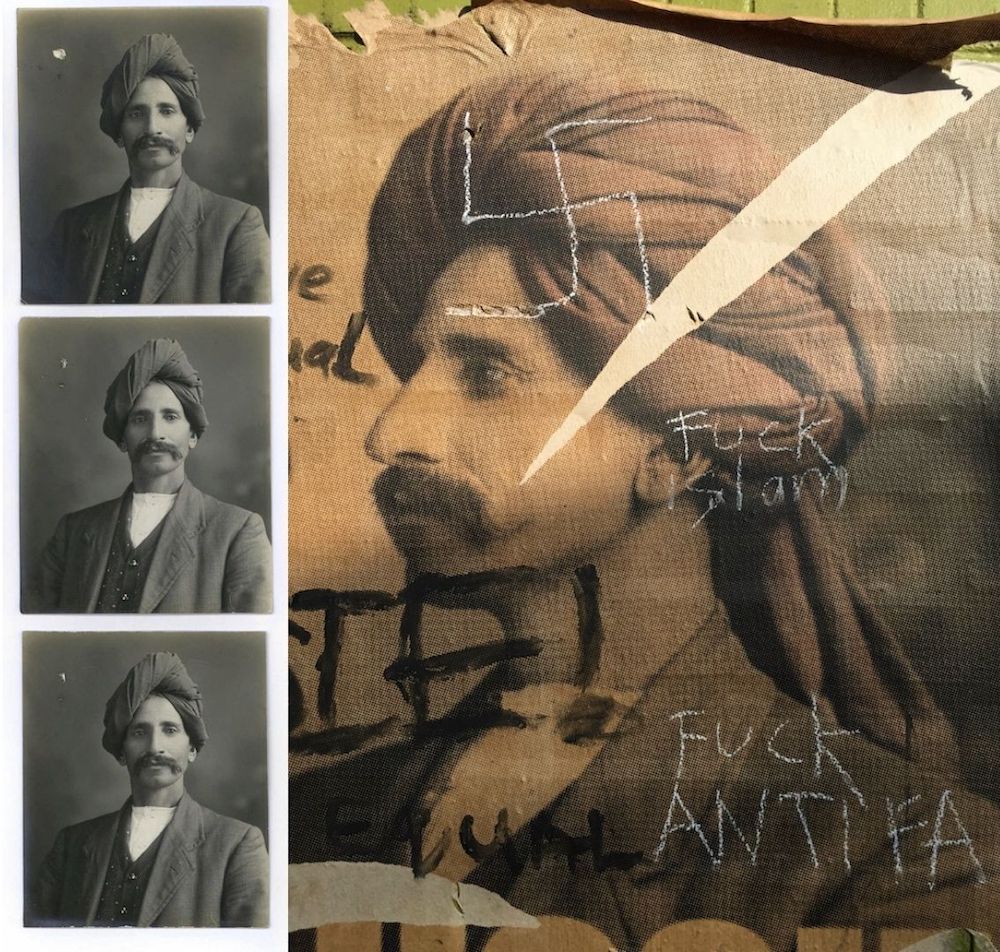

Left: Unknown studio photographer, Passport photographs from Australian government documents for Monga Khan. Monga Khan migrated from Punjab and worked as a hawker throughout the Ballarat district of Victoria in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries. In 2016, he became the unwitting face of a crowd funded anti-racism art project. His likeness, as imagined in the artist’s work, was defaced with racial slurs at Sydney’s Green Park station almost 100 years after his death. Australia, Digital scan. Original document courtesy National Archives of Australia.

Right: Defaced anti-racism poster featuring Monga Khan, Green Park Station, Sydney, Australia, 2019, Digital photograph. Image courtesy Usman Faruqi.

Four generations of descendants of Monga Khan, Birmingham, UK, 2019, Digital photograph.

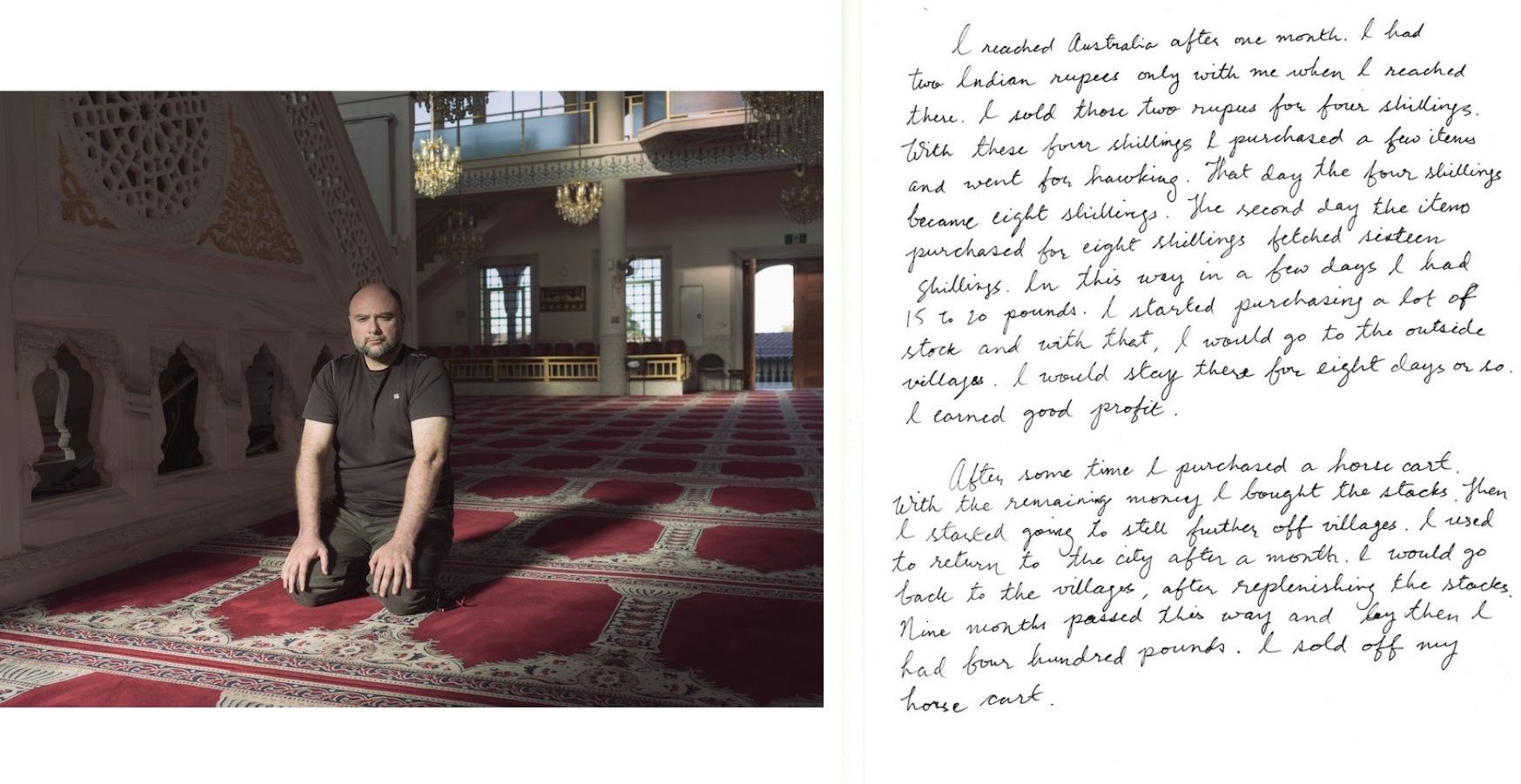

Left: Haroon Bux at the Auburn Mosque. Haroon Bux is the great grandson of Khawaja Bux. The Auburn Mosque in Sydney’s West is a significant place for him. His great-grandfather also helped raise funds for the building of the first mosque in Perth. Sydney, Australia, 2020, Digital photograph.

Right: Handwritten excerpt from Khawaja Bux’s diary, outlining his beginnings hawking in Australia in the early twentieth-century, Australia, Exact date unknown, Digital scan.

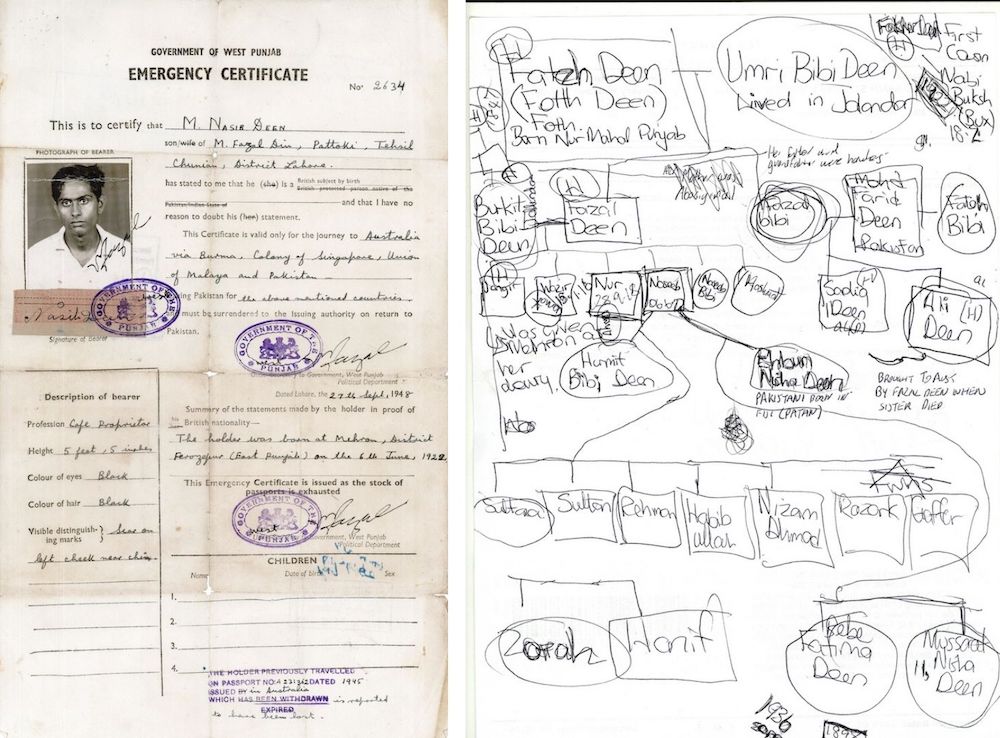

Left: Fazal Deen’s son Nasib’s emergency certificate issued in 1947, allowing him to leave India and return to Australia at the time of the partition of India, Digital scan.

Right: Family tree drawn by Mussarat Nisha Deen, great-granddaughter of Fotth Deen. Fotth Deen began his life in Australia as a hawker after migrating from undivided India as a young man in 1890. Brisbane, 2019, Digital scan.

Left: Top: Unknown Photographer, A Dodge car and a caravan used by Nasib Deen when he returned to hawking during the period 1961-64. Nasib Deen sold cushions specially designed for the rear parcel shelves of cars. They were made in the family home, by his children. Nasib’s children worked for three hours each day after school, hand-making the cushions that were often embroidered with the names of different makes of cars. His main customers were petrol stations and he sold to them primarily on a commission basis. Nasib Deen travelled an arduous route for months at a time, selling the cushions from the North Coast of New South Wales to Cairns in Far North Australia. He initiated this business when his other enterprises came under pressure. Australia, c. 1960s, Digital scan. Original photograph courtesy Deen family.

Right: Unknown Photographer, Fourth-grade photo including Fotth Deen’s great-grandson, Hanif Deen, Brisbane, Australia, 1968, Digital scan. Original photograph courtesy Deen family.

Left: Beechworth Cemetery. A sign at the Beechworth cemetery in North West Victoria. Within the strangers’ section stand two headstones of men from India who worked as hawkers in the local area. It was common for hawkers from India to be interred away from other graves and to be buried rather than cremated, even if their religion specified cremation. Victoria, Australia, 2019, Digital photograph.

Right: Harmel Uppal. Uppal’s great-uncle, Pooran Singh, was an Indian from Punjab who migrated to Australia as a thirty-year-old man in 1899 to earn money for his extended family in India. Pooran worked as a hawker in the state of Victoria and died forty-eight years later in 1947. Throughout his working life in Australia, he sent money back to his family in Punjab. Upon his death he left 1500 pounds in equal shares to his four nephews, as he was never married and had no children of his own. The family used the money to build a house and placed a plaque upon it bearing Pooran Singh’s name. In 2010, Uppal travelled to Australia to repatriate his great-uncle’s ashes to India, after he discovered that they had remained uncollected since his death in Australia sixty-three years earlier. Wolverhampton, UK, 2019, Digital photograph.

Unknown photographer, Ali Buc (right) with unknown compatriot. Ali Buc migrated from Punjab and worked as a hawker around the area near the Grampians in countryside Victoria. He is buried in the Dunkeld cemetery, upon its very edge, sixty-three metres away from the nearest grave. Victoria, Australia, c. 1935, Digital scan. Original photograph courtesy Dunkeld Historical Society, Victoria.

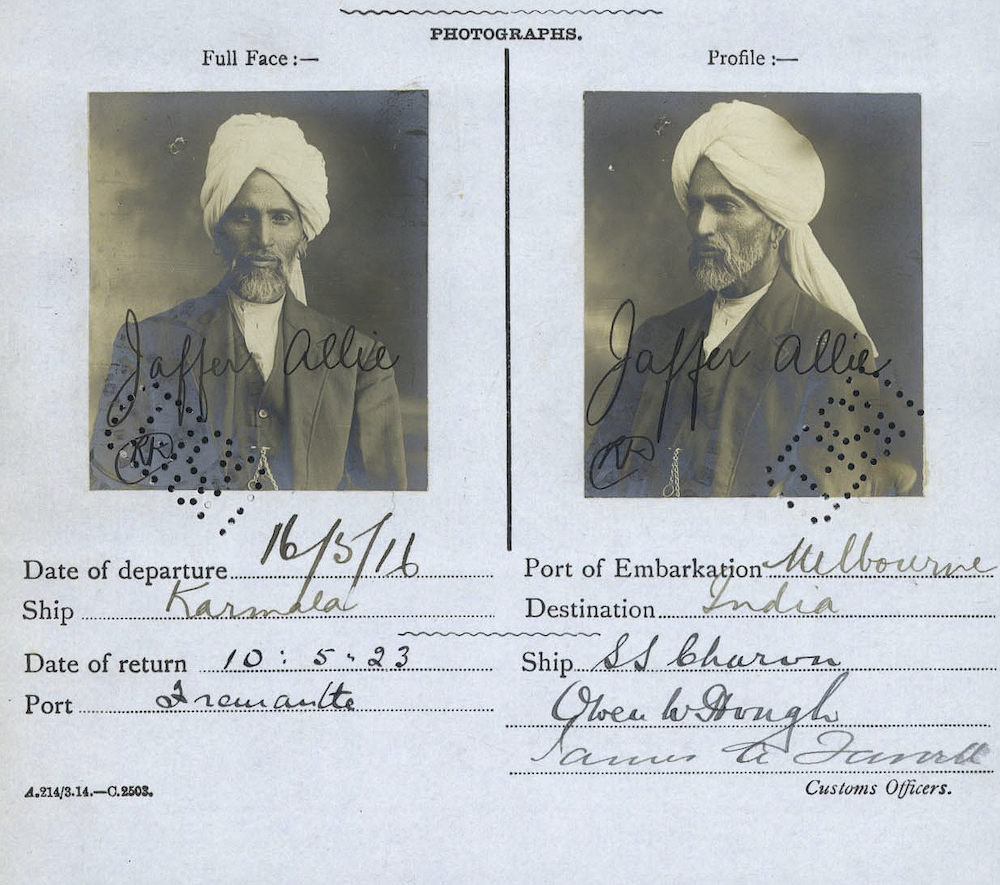

Australian government document issued to Jaffer Allie in 1916, Jaffer Allie, a hawker, was given this document so that he could re-enter Australia on return from visiting India. This certificate meant that the holder did not have to sit a fifty-word dictation test in a language of the customs officers’ choice, as was common for non-Europeans under the White Australia Policy. Australia, Digital scan.

Item sold by unknown hawker in Victoria, Australia, early twentieth-century, Digital photograph.

Yask Desai is a Melbourne-based Australian-Indian visual artist who works with photography, video, archives and text. His work concerns itself with themes of place and collective and individual identity. Desai often combines historical and social research to explore the cultural connections between imagery, history and constructions of identity. His latest work Telia involves a subjective use of visual imagery surrounding the men who migrated from undivided India and worked as hawkers or travelling salesman throughout rural Australia from the late nineteenth-century to the mid twentieth-century. Telia was the name given to Australia by a number of the family members who remained in India.

Dr Samia Khatun is a historian and is Senior Lecturer at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Her documentaries have screened on SBS-TV and ABC-TV in Australia. Her first book, Australianama: The South Asian Odyssey in Australia, was published in December 2018 and won the Scholarly Non-Fiction Book of the Year in the Educational Publishing Awards Australia and was shortlisted for the Douglas Stewart Prize for Non-Fiction, the Multicultural NSW Prize and the Ernest Scott Prize for History. She is currently researching a history of eighteenth-century textiles that bound together Bengal and Britain.

NOTES:

1. W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 8.

Watch Yask Desai talk about Telia:

View this post on Instagram