Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

The Indian in DRUM Magazine

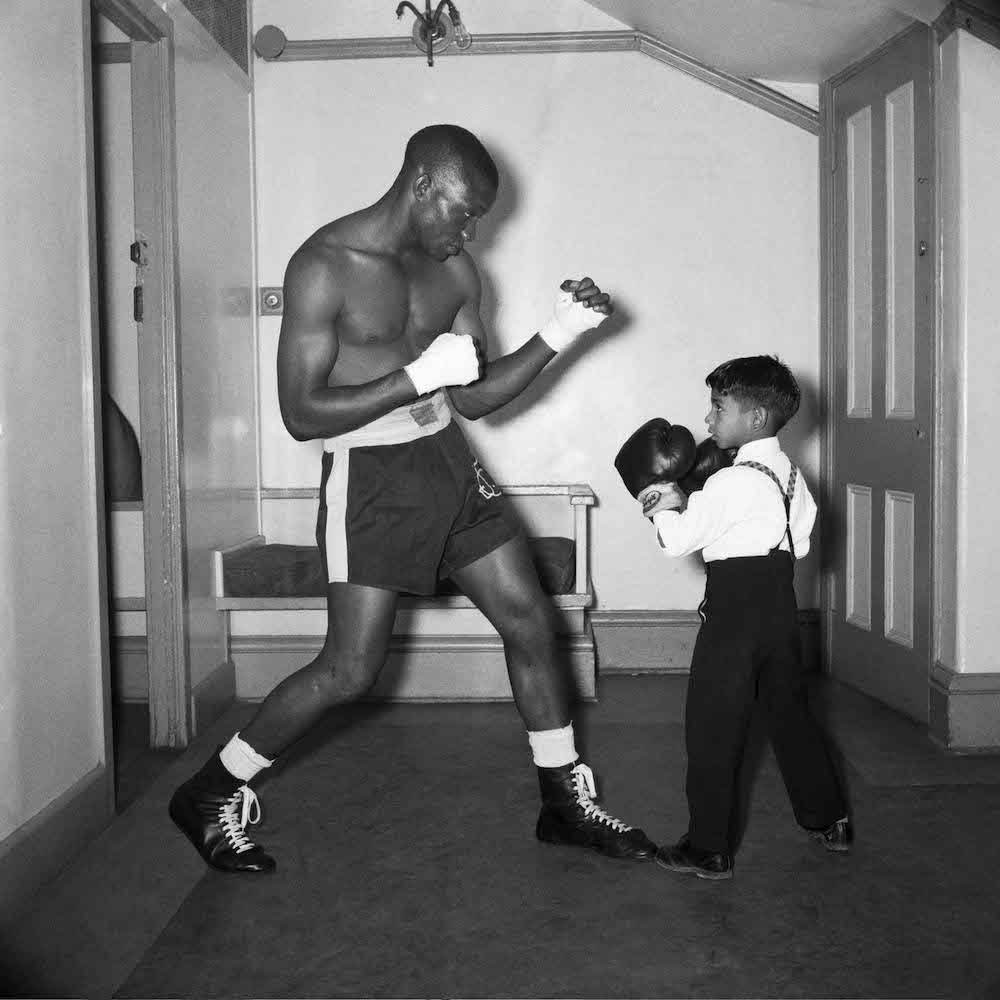

Barney Desai, Mohammed Shaik, son of boxing promoter Tiger Shaik, attended all of Elijah “Ellis Brown” Mokone’s fights in Cape Town in 1956 leading the boxer to refer to little Shaik as his good luck charm. South Africa, 1956, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

It was while discovering “by accident” a set of DRUM publications that South African curator Riason Naidoo finally found visuals that resonated with stories he had heard from his parents. Founded in 1951, this legendary South African magazine remained famous largely for its reportage of black life under apartheid. But the DRUM archive examined and compiled by Naidoo gives us a unique insight into a lesser-known aspect of South African history—the trajectory of its Indian diaspora. Deconstructing conservative stereotypes of the “Indian” propelled by the colonial and then apartheid state, this document offers a nuanced vision of a cosmopolitan society—from football teams to city gangs, domestic spaces to jazz bars— articulated by “black” writers and photographers themselves.

First curated by Naidoo as a photo exhibition, “The Indian in DRUM magazine in the 1950s” has been touring South Africa since 2006 (South African National Gallery, Market Photo Workshop, Durban Art Gallery, Constitutional Hill, etc.) and was published as a book in 2008. Later, he co-produced and co-directed, with Damon Heatlie, the documentary titled “Legends of the Casbah” (2016) that was inspired by the same exhibition and research.

Philippe Calia: Could you start by giving us some context about the Indian community in South Africa and how it had been pictured by the state during the first part of the twentieth-century?

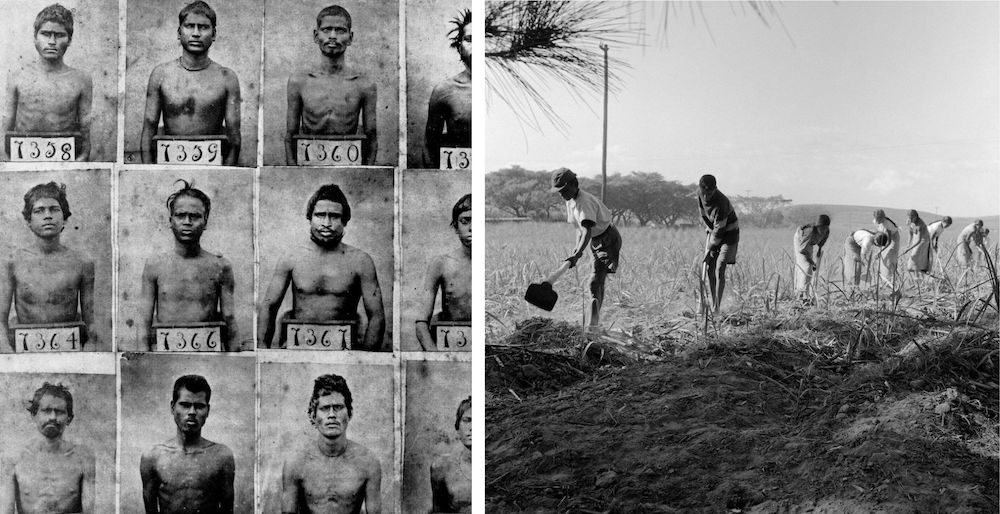

Riason Naidoo: Indians first arrived in the Colony of Natal, around 1860, as indentured labourers. Slavery was abolished in 1833 in the British Empire, so this was only twenty-seven years later. When the Indians arrived, they were more or less treated like slaves. They had to build their own accommodations. They went to South Africa with dreams of making it in a new country, but when they arrived, they were worse off than in India. You can see one of those pictures in the book—of the men with naked torsos, holding placards with numbers. After five years, when many of the labourers were freed of their contracts, they started farming for themselves. Many of them became very successful because they already had farmed in India. They started to compete with the English farmers, with cheaper products. This led to an anti-Indian sentiment, which was actually created by the British and had many negative connotations with regard to Indians—that they were unhygienic and backward, etc. During this time, Gandhi also arrived in South Africa, and took up the plight of Indians against the British as the latter had started to implement new discriminatory laws.

PC: How was the community treated under the apartheid government?

RN: Apartheid had come into effect in 1948. In January 1949, ethnic riots broke out between Indians and Zulus, and that was an important moment. The anti-Indian pogrom started in the inner city of Durban, near the Indian market, but most of the damage was in the suburban areas of Cato Manor. After that, people were moved into racially segregated areas under the Group Areas Act of 1950. So, in the two state publications of 1950 and 1975—which I refer to in my book—the state then took credit for the development of the Indian in South Africa from near slave to a middle-class citizen. It said that it was thanks to apartheid that the Indian had come a long way in South Africa. It used the “Indian” as a kind of example and took credit for their “progress.” The apartheid state created a number of media agencies in the United States of America, Europe and elsewhere, in order to circulate these kinds of documents. It was a kind of international propaganda campaign to counter the negative impression of South Africa under apartheid.

PC: The DRUM issues on which you focused your research were from the 1950s, correct?

RN: The original DRUM printed copies were from 1951 until 1984. The magazine was then sold to a South African government organization (Naspers). The Bailey family kept the archives (in Johannesburg) under the name Bailey’s African History Archive (BAHA). The people who grew up in the 1950s know about DRUM not only in South Africa, but in Anglophone Africa as well. Also, there have been many exhibitions done on DRUM magazine, including Okwui Enwezor’s In/Sight in 1996 at the Guggenheim Museum. Enwezor also did Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, a big photo show, which was displayed at the International Center of Photography in New York and at Museum Africa in Johannesburg, as well as in Germany at the Haus der Kunst. Enwezor was very familiar with DRUM and the impact that it had. As he mentioned, it was distributing 450,000 copies a month in the 1950s, across Africa in Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya. G.R. Naidoo was the Editor of DRUM in Durban and set up the Kenya office.

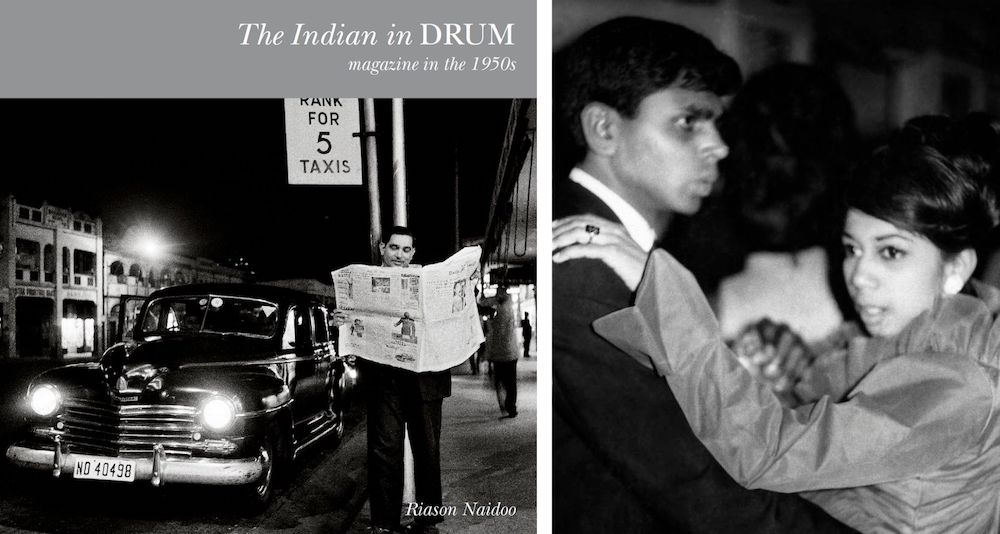

Left: Cover of The Indian in DRUM magazine in the 1950s, image by Ranjith Kally, Cape Town: Bell-Roberts Publishing, 2006. Right: Unknown photographer, Riason’s parents, Mogambery and Saras Naidoo, at a ballroom dance hall, Durban, South Africa, early 1970s, Silver gelatin print.

DRUM became of transcontinental African Anglophone magazine. Stories from South Africa were shared with stories from the West African region or the East African region. This was quite something for that time—the 1950s. What was very important about DRUM was that the stories and the photos were mainly taken by black photographers, with the exception of Jürgen Schadeberg and Ian Berry. When I say “black,” I also include those of Indian descent. The writers were from these communities as well—like G.R. Naidoo, Ranjith Kally and Es’kia Mphahlele, Peter Magubane, Alf Kumalo or Bob Gosani in Johannesburg. At the DRUM office in Durban there was, at first, G.R. Naidoo, then he was joined by Ranjith Kally. While both already had experience in photography, they were not trained at DRUM, as was the case with those in Johannesburg. In Durban, they were already experienced photographers—Gandhi created his own printing press in Durban in 1898 to publish the Indian Opinion from 1903. So, there was a long tradition of printing in this city, with the Indian communities printing their own newspapers in Gujarati and Tamil.

PC: Is there a new image of the community that we see at play in DRUM throughout the 1950s?

RN: The golden age of DRUM was the 1950s, commonly called the “DRUM Decade.” At that time, because the apartheid laws had only started to be implemented, there were still places that were mixed—Sophiatown in Johannesburg, Cato Manor in Durban, Marabastad in Pretoria, District Six in Cape Town, etc. And then in 1960, Sharpeville changed everything; there was a massacre in which many protesters were killed. 21 March 1960 marked a violent turning point in apartheid. In contrast, the 1950s in South Africa is comparable to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s in the USA. And there is a link between the two, because American movies were very popular from the 1930s to the 1950s in South Africa and influenced the black populations that started to emulate Jesse Owens and Joe Louis in sports; and Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday in music. In South Africa, you had Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela as well as Abdullah Ibrahim on piano. And there were jazz clubs that were multiracial. So, people of all racial backgrounds would meet there, even though the apartheid laws forbid it. In the DRUM archives we find images of these jazz clubs. Owned by Pumpy Naidoo and his brother Nammy, the Goodwill Lounge hosted not only local musicians but also international jazz artists and bands like Tony Scott and Jazz West Coast from the USA. One of the pictures features Bud Shank, a famous flautist and saxophonist back then, and we also see interracial romance, as it were, between singers Miriam Makeba and Sonny Pillay.

We see this diversity even in the gangs—such as the Salots, which was interracial. Their leaders were killed by the Crimson League, another gang of 300 working-class Indian men that arose from the market. The Crimson League also had a football club. It was one of the first Indian football clubs founded in Durban, in the 1890s. Football was a very, very important sport, along with boxing and, what they called at the time, physical culture. Football attracted huge crowds at Curries Fountain. We also see images of the emergence of a modern Indian woman, as a professional, with university degrees; we see this kind of modernization happening in dress too. There are stories of Indian women wearing bikinis and G.R. Naidoo did a three-series feature on that—interviewing people and what they thought about it. Some were for it and some were against it, as usual. Then there are people like Dr Goonam, who was an activist and a feminist. In the 1960s, she defended the right to abortion. She was imprisoned eighteen times in total for her political activism and wrote an autobiography entitled The Coolie Doctor.

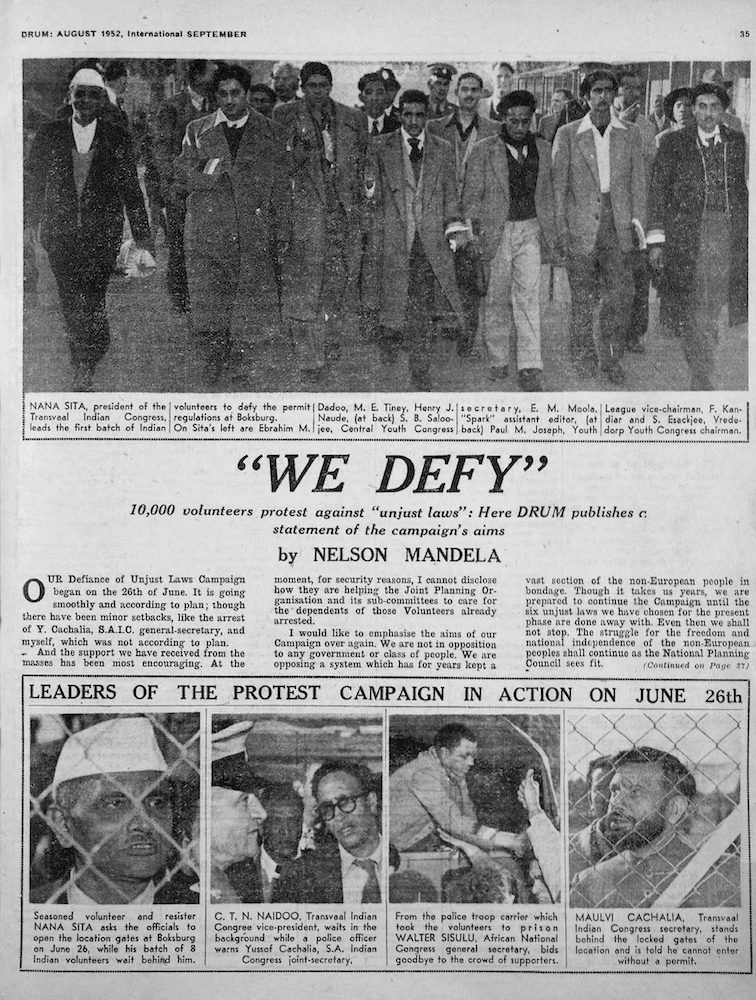

Going back to the representations that we find in DRUM, we also find other activists like Monty Naicker and Yusuf Dadoo, who led the Natal Indian Congress and the South African Indian Congress. They eventually teamed up with Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo and other African National Congress leaders.

PC: Can you tell us more about the role of the Indian diaspora in the politics of resistance in South Africa?

RN: The African National Congress was founded in 1912. It celebrated 100 years in 2012 and is, therefore, one of the oldest existing political organizations in Africa. The organization adopted a position of passive resistance, which came from Gandhi’s legacy in South Africa. This was shown as a means of working within the law, but of resistance as well. The African National Congress started with a passive resistance campaign and only changed its strategy after the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960, when it adopted an armed struggle against the apartheid government. All that time—from 1912 to 1960—it was a peaceful movement that only used passive resistance. Then, there were the Natal Indian Congress and the Transvaal Indian Congress that were started when Gandhi was in South Africa. Even though Indians only made up 1 per cent of the population, they had an enormous influence as political activists. And later, in the first government of Nelson Mandela, you had a minister—Jay Naidoo. He was the leader of the Council of South African Trade Unions, the most powerful figure in the trade unions in the 1980s and 1990s. There were many Indian activists included by Nelson Mandela in the first democratic government…

In the end, you were either white or non-white. Amongst the non-white, you were African, Indian or coloured—meaning mixed descent. These were the three categories under apartheid South Africa. “Black” was a unifying term, it was a kind of political identity against the white oppressive regime.

Personally, I considered myself to be black, because we were fighting against the apartheid ideologies even when I was growing up. We identified as black, we also identified with the African-Americans, even though I have Indian origins. We only listened to soul music and jazz. I did not listen to white musicians growing up under apartheid; it was a kind of political solidarity. I think you can find some resonance with this in the UK, where you have Asians who also identify with black culture— especially activists. In South Africa, it developed into a collective term—black. It is a more positive term than saying “non- European” or “non-white.”

PC: Did Gandhi have a larger role to play in South Africa?

RN: Gandhi had referred to Africans in a derogatory way. I think much of that was also to align himself with the British— to perhaps earn their favour, and to receive validation from the British that the Indian struggle was different from the African struggle in South Africa. He was very focused on the Indian struggle only. But as the politics evolved, people like Monty Naicker and Yusuf Dadoo were embraced by the African community, as they were part of the collective black leadership against the apartheid state.

PC: In Naicker and Dadoo’s case, they were also born and brought up in South Africa, and thereby more South African than Indian, could one say that?

RN: At the end of our film, there is a reference to that. Monty Naicker and Yusuf Dadoo were invited to India by Gandhi in the 1940s and were interviewed by a radio station. Dadoo said, “I am going to speak in English because my Gujarati is not so good.” Naicker said that he was going to speak in Tamil. So, at the end of the interview, the radio presenter said, “I am not sure what language you spoke…” meaning that the two had lost touch with their Indian roots and their languages had creolized into something new; languages that those in India did not recognize.

Unknown photographer, Riason’s maternal grandfather—A.S. Pillay (1904-88)—whose family arrived in Durban in 1878 from the village of Chingleput (between present day Chennai and Puducherry in South India). He is pictured (seated row on the extreme left in a dark costume) with cast members from a play. Pillay looks around ten or twelve-years-old. Durban, South Africa, c. 1914-16, Silver gelatin print.

Unknown photographer, Riason’s paternal grandfather, G.V.P. Naidoo (seated row–third from left) as a player of Junction Football Club. He was already a third generation Indian in Durban. G.V.P.’s grandfather had arrived in Durban in 1878, also from the village of Chingleput. Durban, South Africa, 1924, Silver gelatin print.

Left: Unknown photographer, Nineteenth-century identity photographs of male indentured labourers who first arrived in Durban from India in 1860. Their colonial numbers were passed down to their descendants. Durban, South Africa, c. 1860s. Courtesy of Government Information and Communication System (GCIS), Pretoria. Right: Unknown DRUM photographer (possibly Ranjith Kally or G.R. Naidoo), Working eight hours a day on the sugar farms outside Durban, “Indian” children did adults’ work for a fraction of the salary. Some were not even ten-years-old. South Africa, 1957, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

“We Defy,” In 1952, for the first time in South Africa’s history, the African National Congress joined forces with the South African Indian Congress and many other non-European organizations to form a united front in the Defiance Campaign, a series of public protests against the unjust and discriminatory apartheid racial laws of the minority white government. Here, Nelson Mandela writes for DRUM about those active in the demonstrations in Boksburg, outside Johannesburg. “Indian” political activism in South Africa was ignited during Gandhi’s years in the country from 1893- 1914, in which he led a series of passive resistance protests. Copyright BAHA

Jürgen Schadeberg, 800 “Indian” school children outside the Johannesburg Court show their solidarity for leaders imprisoned during the 1952 Defiance Campaign, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1952, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

Left: Ranjith Kally, Pataan was a gangster for hire, employed by Durban businessmen. Durban, South Africa, 1958, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA. Right: Ranjith Kally, Members of the Crimson League gang during court recess, where seven members of their gang were charged with the murder of former gang member Michael John. Durban, South Africa, 1957, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

Ranjith Kally, Internationally renowned clarinet player Tony Scott plays with local jazz musicians, including Lionel Pillay on piano, at the Goodwill Lounge. Whenever musicians and celebrities came to Durban they made a stop at Pumpy’s jazz joint. Durban, South Africa, 1957, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

Ranjith Kally, Sonny Pillay and singer and activist Miriam Makeba (with Sonny’s family) were the South African “black” glamour couple of the 1950s and part of the King Kong musical cast that left the country for London. Durban, South Africa, 1959, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

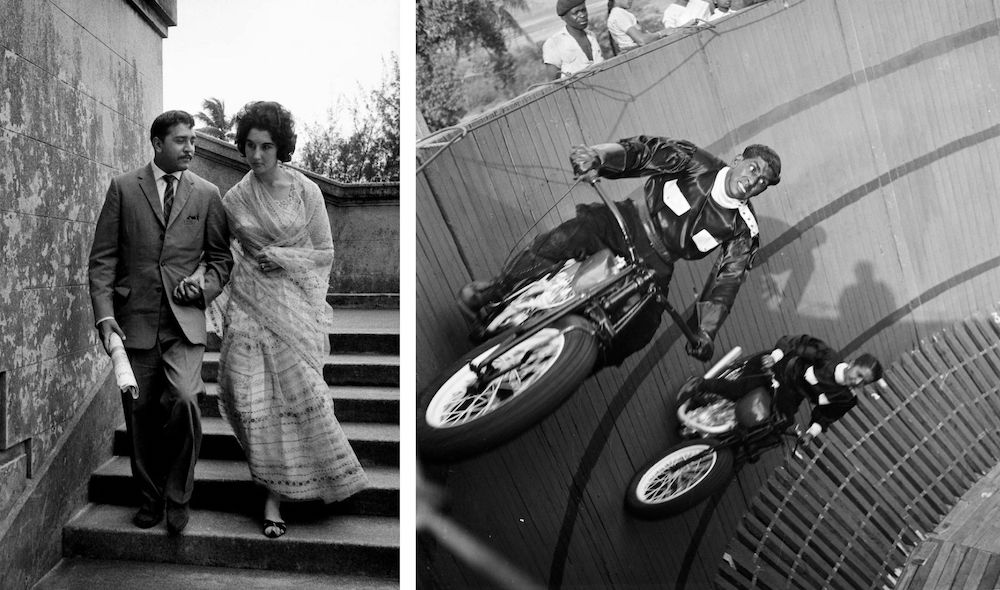

Left: Ranjith Kally, Syrub Singh, an “Indian” businessman, met Rose Bloom, a European, who worked in the passport office in Pretoria. Marriages across racial lines were illegal under apartheid South Africa (1948-94). The two eloped to Lourenço Marques (current day Mozambique), but were arrested on their return to the country. Pretoria. South Africa, 1959, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA. Right: Ranjith Kally, Stunt riders Tommy Chetty and Amaranee Naidoo on the “Wall of Death.” The bohemian duo toured the country in a caravan with Chetty’s fair and performed their death-defying stunt for audiences in little towns and suburbs along the way. Durban, South Africa, 1957, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

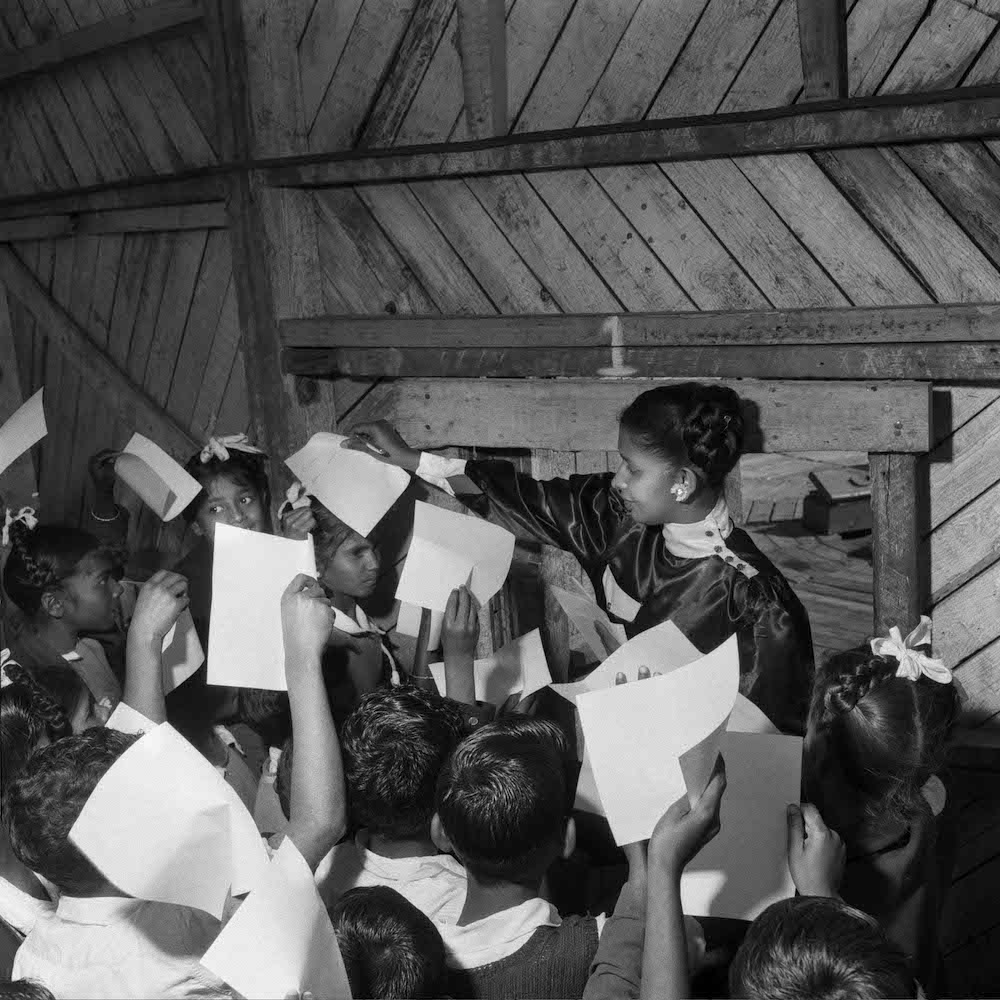

Ranjith Kally, “Wall of Death” stunt rider Amaranee Naidoo signs autographs for young fans. Durban, South Africa, 1957, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

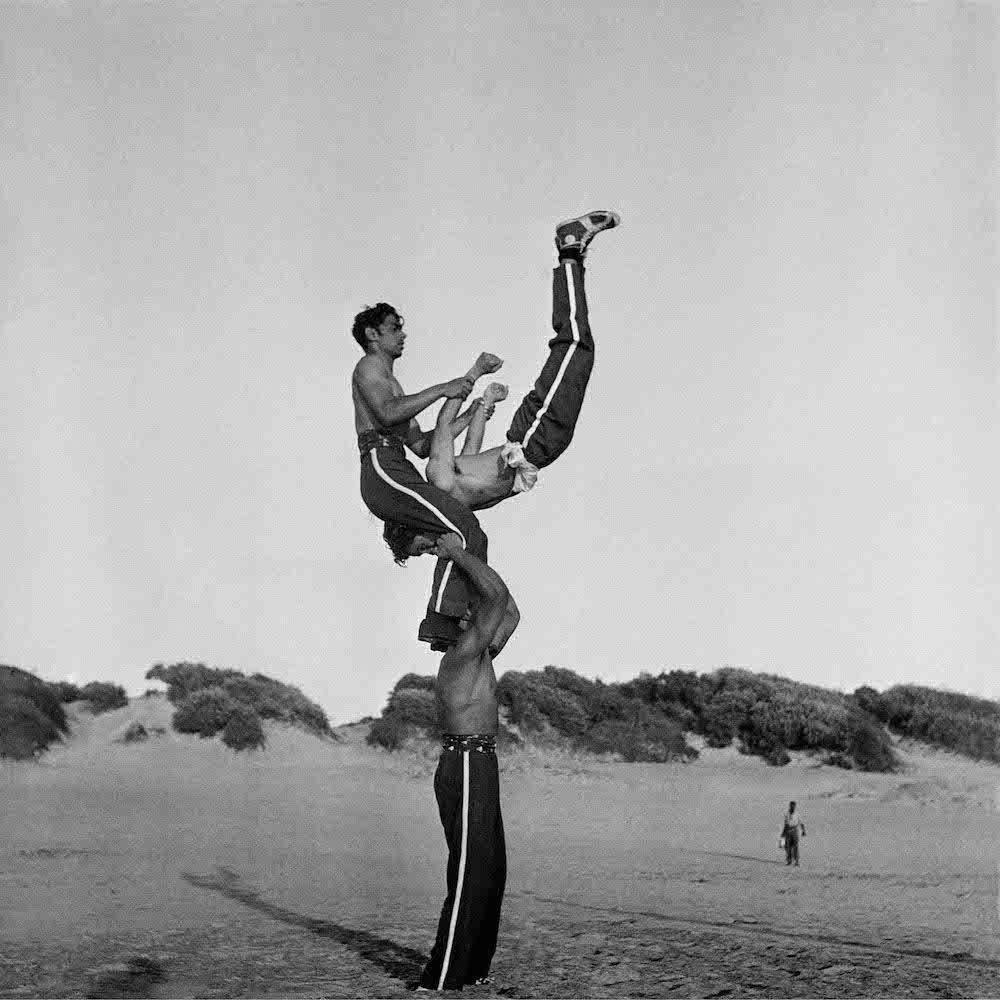

Jürgen Schadeberg, Three members of the Sonny Moodley Troupe in perfect timing on a Durban beach. South Africa, 1952, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

Left: Ranjith Kally, Rita Lazarus, “Miss Durban” in 1960, looks totally comfortable in a bathing costume, which was the subject of a series of articles by G. R. Naidoo in the 1950s that focused on the modern “Indian” woman. Durban, South Africa, 1960, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA. Right: G.R. Naidoo, One of the few professional women photographers of her time, Priscilla Moodley, also occasionally took pictures for DRUM magazine. Durban, South Africa, 1960, Silver gelatin print. Copyright BAHA.

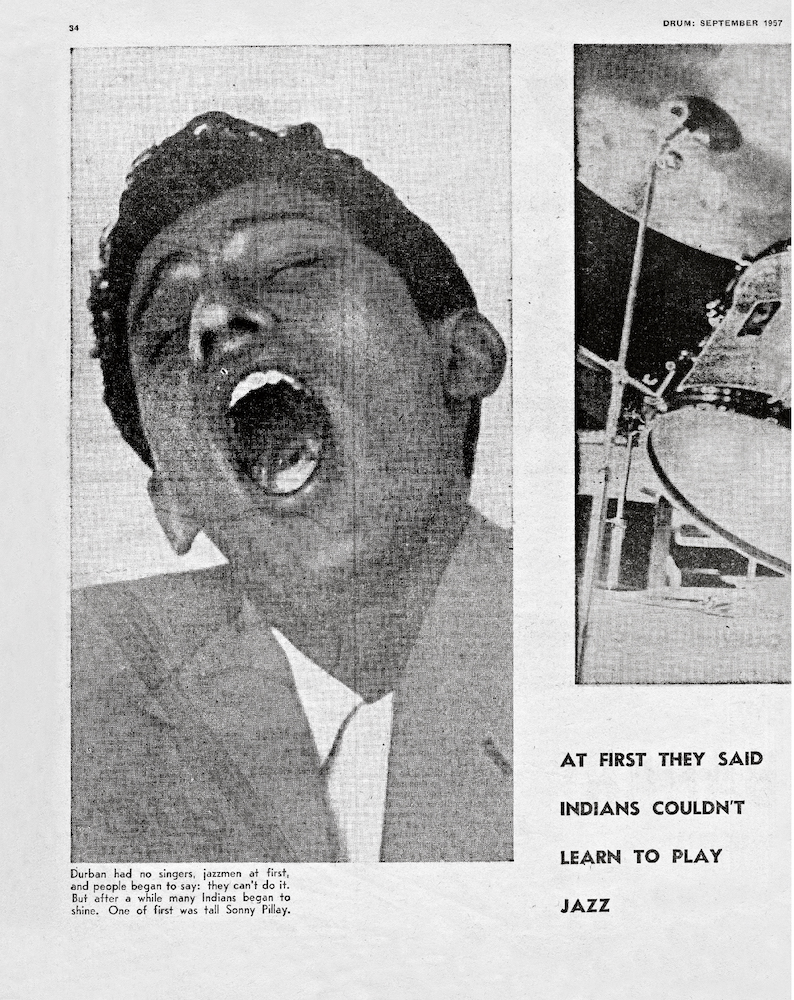

Indians play Jazz, Singer Sonny Pillay—featured here in DRUM magazine in 1957—enthralled crowds at the Goodwill Lounge in Durban and played with the likes of the legendary Miriam Makeba, local pianist Lionel Pillay, and renowned American clarinetist Tony Scott. He was part of a groundbreaking generation of “Indian” jazz musicians from Durban along with the outstanding drummer Gambi George. Both musicians left South Africa during apartheid to seek greener pastures, with Pillay moving to New York and George to Sweden. South Africa, September 1957. Copyright BAHA.

Riason Naidoo is an independent curator, writer and researcher focusing on modern and contemporary African art, currently based in Paris. Born in Durban, Naidoo graduated with a BA and MA in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Initially practicing as an artist, since 2004 Naidoo has curated exhibitions that highlight repressed South African and African art histories. Exhibition highlights include neuf-3 (2021), Any Given Sunday (2016), 1910-2010: From Pierneef to Gugulective (2010), The Indian in DRUM magazine in the 1950s (2006). He curated exhibitions on artist Peter Clarke shown in Dakar, London and Paris (2012-13) and on photographer, Ranjith Kally shown in Durban, Johannesburg, Cape Town, Bamako, Saint-Denis (Reunion Island), Vienna, and Barcelona (2004-11). He was co-curator of the tenth edition of the Dak’art Biennale (2012) and director of the South African National Gallery from 2009 to 2015.