Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Turbine Bagh

Assorted Turbine Bagh samosa packets, London, UK, 2019-21, Digital photograph.

UK-based Bangladeshi architect and artist, Sofia Karim, has always created work that edges into the space of social activism. A watershed moment that spurred this form of engagement further was the abduction of her activist-photographer uncle, Shahidul Alam, in Dhaka. His sudden imprisonment triggered a number of global incidents—including protests with visual images, texts and signs to free him—as a part of the Free Shahidul Campaign. Karim took a lead role in the campaign in London, along with the support of close allies in South Asia.

In this interview, Karim discusses the impact of Alam’s imprisonment on her work along with the transformation brought by an Instagram account, Turbine Bagh. Set up in 2020 as a response to the Shaheen Bagh protests in Delhi, it took the form of images and works from contributing artists and photographers for the cause. Karim describes how Turbine Bagh has transitioned into a platform that adapts itself to other situations and campaigns in the region, such as Where is Kajol? She also addresses this form of activism as something that keeps her connected with the region she identifies with, as a part of the South Asian diaspora. Though Turbine Bagh was initially planned as a one-day protest performance at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, the samosa packets that she made for the event ended up in storage in her studio during the Covid-19 pandemic. Subsequently, the work was shortlisted for the Jameel Prize (2021) and is currently being exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

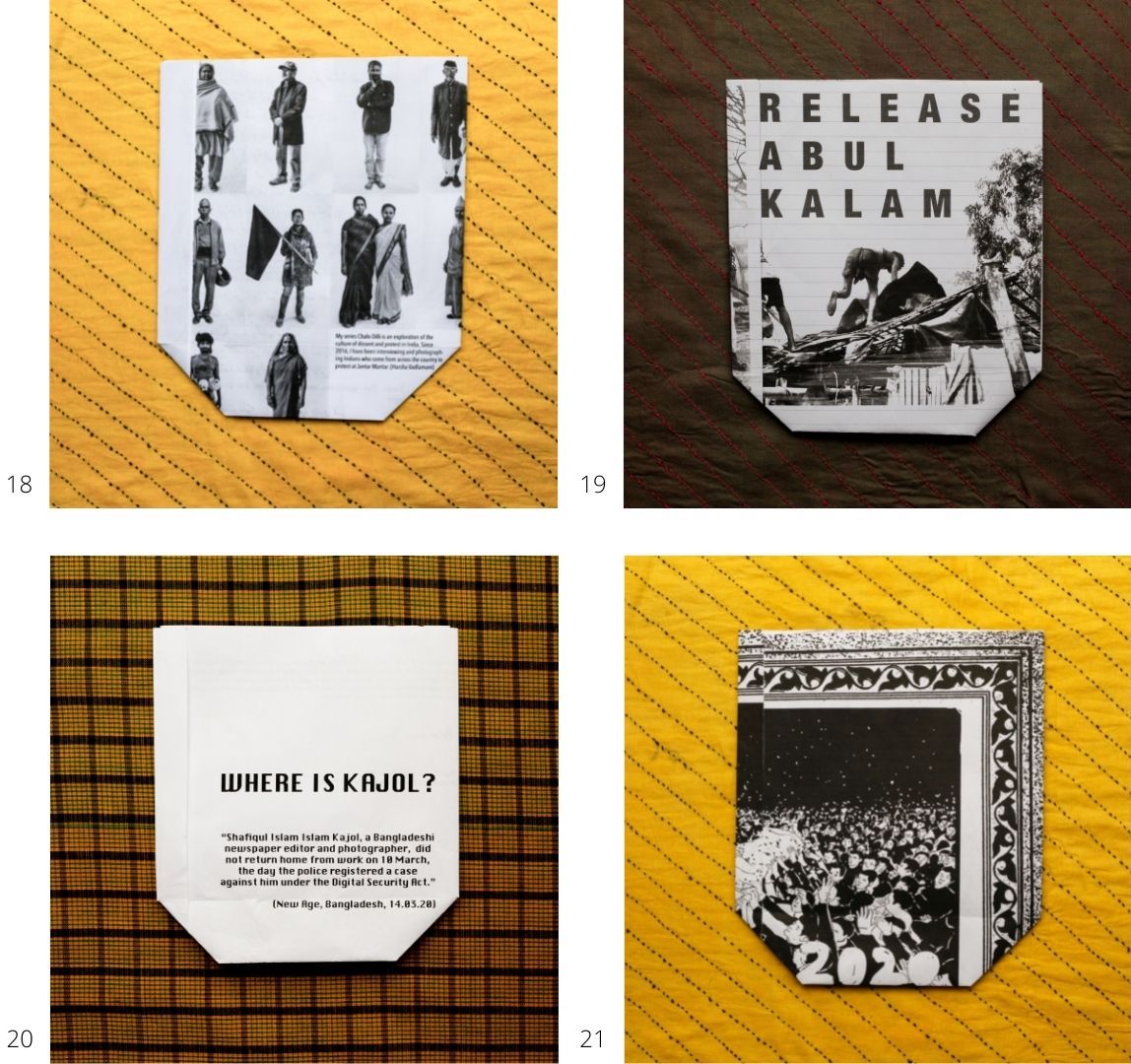

Veeranganakumari Solanki: Once Shahidul Alam was released from prison, a number of conversations with him led you to create a quieter series of drawings and essays titled Architecture of Disappearance (2019). The project also included architectural models in response to the Keraniganj jail cells that your uncle described to you. Could you speak about the location of the image within your architectural practice—where do the overlaps and departures lie?

Sofia Karim: There is always a lot happening for me in terms of personal, quieter images behind my activism campaigns. During Shahidul’s incarceration, I used to imagine and construct the spaces he occupied in my mind. I wanted to crawl into his cell like a worm and hold his hand. When he was tortured in custody and held in remand for interrogation, my mind roamed spaces that were formless and raw. Spaces I had never encountered or considered before. They were made up of mainly emotions and colours; formless and scaleless in the way they expanded and contracted. I was reminded of how Shahidul taught his students to think of colours they had never seen before by burying into their earliest memories. When he was released, I made drawings and models based on the stories he told me of the jail he was in. Some were figurative drawings, with characters like old Koutuk Da (a fellow prisoner who would roam around accompanied by around seventy cats) or bodies crammed into cells in “kechki file” and “ilish file.” Kechki and ilish are two types of Bangladeshi fish. To pack prisoners into the holding cell at maximum density, they were made to arrange their bodies into kechki file—where they would lie opposite each other with their legs scissored together, groin to groin. If they paid a little more, they were allowed to position themselves in ilish file—where they would lie on their side, allocated about ten inches of space each. I also made abstract drawings of this, where I turned the bodies into vectors in space. My vocabulary of architecture began to change.

Today, my human rights work plays a significant role in everything I design. For instance, I recently designed a garden room and based it on the case of the Bhima Koregaon prisoners (BK16) and the frescoes of Fra Angelico. I conceived it as a simple, public space consisting of sixteen gardens dedicated to political prisoners and as a shelter for contemplation. The model I made for it has texts from the May 2021 bail hearing of Father Stan Swamy, a Jesuit priest and tribal activist who was one of the BK16 prisoners. Father Stan Swamy was still alive when I designed it, but died weeks after. When I heard about his death, I was shaken. I entered that space I had built in my mind, longing for the stillness and solace that architecture can provide. When I wrote a letter to Dr Anand Teltumbde—who is also one of the BK16—I formed it as an actual model, one that unfolds as a three-dimensional stair in a garden. I wanted to offer him another world, a way to escape into the image. I used soft paper, so the sound of it unfolding would not cause any hurt. So, I suppose these are ways in which images translate into architectural spaces in my work.

Memories of Keraniganj Jail models by Sofia Karim, Rubin Museum, New York, 2019, Photographs by Shahidul Alam.

VS: As a person belonging to the South Asian diaspora in the UK, how has Turbine Bagh expanded the online space of activism for you into a wider, amplified and powerful political commentary?

SK: I barely used social media until my uncle was jailed. Then, in 2018, the Free Shahidul campaign changed this.

In January 2020, I set up Turbine Bagh on Instagram to gather artworks for the protest we were planning at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in solidarity with Shaheen Bagh and the Citizenship (Amendment) Act protests in India. The museum was closed due to Covid-19 lockdowns in March, but the online platform continued and began responding to other calls for action. We got news of Bangladeshi photojournalist Kajol’s disappearance. My daughter made a Where is Kajol? samosa packet which we posted on Instagram and Kajol’s son messaged us! He had seen the packet and was desperately trying to protest for his father at a time when no public gatherings were allowed. So Turbine Bagh launched its first digital human chain for Where is Kajol? What was really lovely was the cross-border support. Several Indian artists sent in artworks and posters to support and amplify the campaign. Ever since, there have been similar campaigns with artists from across the world sending in their artworks.

As a British-Bangladeshi, why is my work centred on Bangladesh and India? It is because that work makes me feel alive. I have felt connected to Bangladesh all my life. The connection goes beyond language, but it also has something to do with escaping the prism of racism, Islamophobia and feelings of alienation. The activism came later. The horror of where we are—politically and socio-culturally—in both countries cannot be overstated. If this trajectory continues, the future is imponderable. International solidarity must play its role in the struggle as it has in previous and ongoing liberation movements, such as Black Lives Matter and the Palestinian Liberation Movement, which have gained traction from being taken up globally. For all the bleakness of fascism and authoritarianism, the resistance movements of India and Bangladesh are inspiring. And they are far more progressive than anything I see here in the West. In terms of women’s movements for instance, I have never seen anything like Shaheen Bagh here. And environmental campaigners, or tribal activists—such as Father Stan Swamy, who worked with indigenous communities for fifty years—do not seem to exist here. Environmental activism here is detached from real contact with the most vulnerable on this earth. They do not invite indigenous communities from the majority world to their summits. Often operating in a white, middle-class bubble, they conveniently separate sustainability from human rights, social justice, imperialism, colonialism and military policy. When I look at the resistance in India, I see the strong organization of women, a rallying together of religious minorities, as well as oppressed castes, farmers, labourers, indigenous peoples, environmental activists, etc. Turbine Bagh also exists to raise awareness and expand our understanding of “progressive” and “backward” cultures.

VS: With specific reference to community, could you speak about the responses to Turbine Bagh and its outreach to local communities in South Asia, the UK diaspora and other audiences internationally as well?

SK: South Asia Institute Chicago (SAIC) exhibited Turbine Bagh as did Format Photo Festival in the UK in April 2021. It was also exhibited at the Peckham 24 Photo Festival in London in September. However, the South Asian diaspora “art scene” in the UK has shown little interest in Turbine Bagh (apart from a few individuals). UK diaspora activists and non-art-world followers, however, have been hugely supportive and engaged, including students who invited us to protest at Trafalgar Square, such as the one held in June 2021 to mark one year since the arrest of Pinjra Tod activists Devangana Kalita and Natasha Narwal.

In terms of artist engagement, prime interest comes from artists based in India, less so from Bangladesh (where the interaction arises more from writers and activists). The platform has a surprisingly large following from some loyal, non-South Asian artists and supporters. I remember getting despondent when a Free Ruhul samosa packet got barely ten likes. But, then, Sadie Bridger, an artist in New York made a video piece in March 2021 about the Bangladeshi writer Mushtaq who died in prison, and his co-accused cartoonist Kishore who was still jailed at the time. Sophia Moffa, an Italian artist based in the UK, made a video on Professor Saibaba that she has subsequently exhibited. Rachel Spence, a UK-based poet, journalist and arts writer has participated in numerous Turbine Bagh campaigns. She has written haikus about jailed prisoners in India and Bangladesh apart from writing letters to prisoners. These are people who constantly engage with Turbine Bagh—dedicated comrades. You never know where your support base is going to come from. I made so many friends.

Left: Samosa packet made from court listings, bought on the street of Dhaka, 2019. Photograph: Sofia Karim

Right: Seven-year-old Lylah makes a Where is Kajol? samosa packet, London, UK, 2020, Digital photograph.

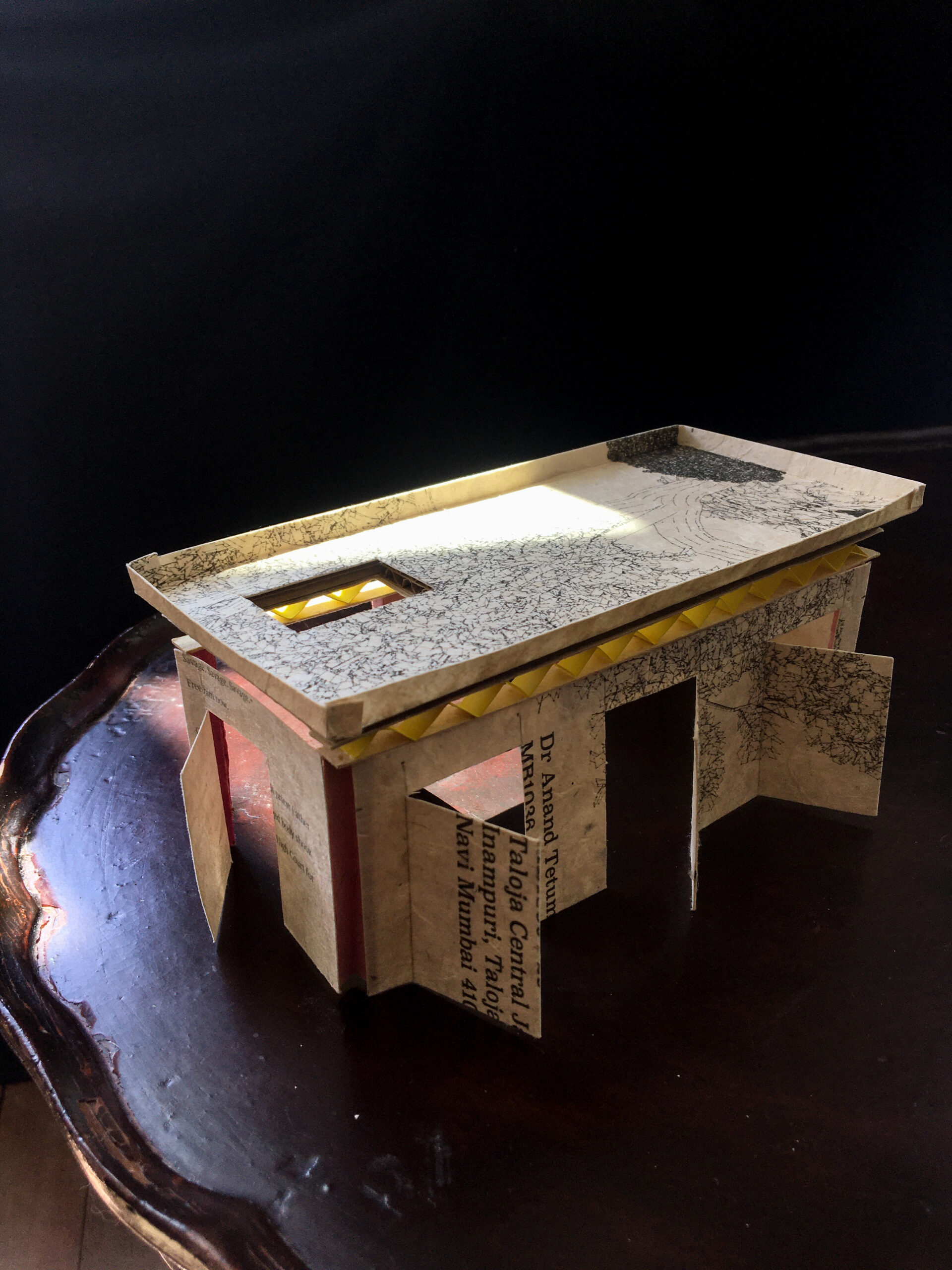

VS: The samosa packets have been a central part of Turbine Bagh. When and where did these originate from and what were your intentions behind circulating the images and texts sent in by other artists? Alongside this aspect, could you also address the authorship of the artworks given this widespread sharing—first digitally on social media and now in the physical formats?

SK: In February 2018, I bought some samosa (shingara in Bangla) in Dhaka, Bangladesh outside DRIK Picture Agency. The packet intrigued me—it had a certain charge and power that I just knew would become significant in my work someday. It was made from waste printouts of lists of court hearings of cases between citizens and the state. I took photos of it in the evening light and began collecting other packets. Collectively, they painted a portrait of a country. When my uncle was jailed, I remembered that packet in Dhaka and wondered if his court listing would ever appear on a samosa packet. This is when I began making Free Shahidul samosa packets for the movement that had spread across the globe. In a climate of press censorship, these packets could offer alternative narratives and reach different audiences.

In 2019, when I was planning Turbine Bagh at Tate Modern, I read an article describing the importance of food at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi. I instantly knew that samosa packets as “protest art” were the answer here. They were familiar to anyone at Shaheen Bagh, yet they carried messages of local resistance and international solidarity. The images were gathered through an Instagram open call to which artists, writers, poets and thinkers responded with images, drawings and texts. I had no budget, so I used old papers from home and my mother’s ink-jet printer to make the packets. The artists shared their works with incredible generosity and not one of them complained about the way their images were used. Each artist was credited for their work and when the work was installed at the Victoria and Albert Museum, all the artists and contributors’ names—including mine as the initiator—have been listed alongside the ninety samosa packets. This is the spirit of activism. Working quickly, efficiently, generously and in good faith. Our work is a means to an end.

VS: In a museum space, where preservation and presentation are so important; how do you respond to the initial intent of immediacy and ephemerality of a work such as Turbine Bagh, that is not archival? How do you situate this project in the spectrum of time?

SK: When I sent the packets to the museum, I was happy but felt that a piece of me had gone. The packets had become members of my family. I had them filled with rice, and had them standing all around the house. Each one told a story. Some would remind me of prisoners still in jail: Umar Khalid, with his finger in the air, said to me, “Do not forget!” Saibaba, in his wheelchair, said to me, “I am in pain.” Some people have images of saints or deities around their house and I had these. To me they have never been museum objects. However, it is important that they are going to be shown in a museum. We also need to reach these audiences and raise awareness. Even if the paper disintegrates, these objects have both witnessed and participated in a much larger historic civil rights movement.

1. Delhi Pogrom, featuring artwork by Younus Nomani, March 2020. 2. Free Umar Khalid, featuring a photograph by Rohit Saha, December 2020. 3. Nepal Resistance – Uma Devi Badi stages a petticoat protest, featuring a photograph from Jagaran Media Center/Nepal Picture Library, March 2020. 4. Free Saibaba, featuring artwork by Lokesh Khodke, July 2020.

5. You cannot burn humanity, featuring a statement by Vijay Prashad, March 2020. 6. Hum Dekhenge, featuring musical score by Oliver Weeks, March 2020. 7. The Price of Gratitude, Tribute to murdered student Abrar Fahad, featuring a photograph and poem by Shahidul Alam, February 2020. 8. Where is Kalpana Chakma?, featuring a photograph by Shahidul Alam, August 2020.

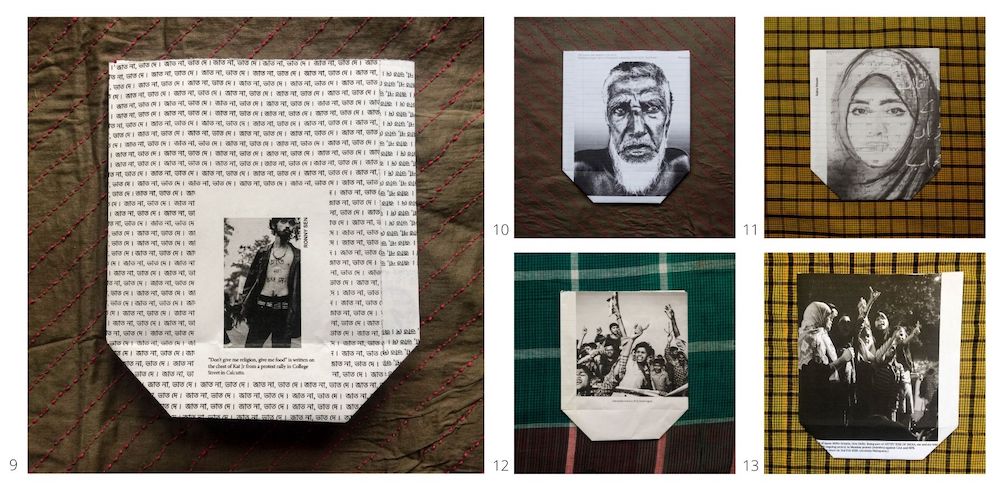

9. Don’t give me religion, give me food, featuring a photograph by Ronny Sen, February 2020. 10. Release Abul Kalam, featuring a photograph by Abul Kalam, December 2020. 11. All of Us Women, featuring artwork from Saba Hasan with text by Nabiya Khan, March 2020. 12. Dalit protest in Una, 2016, featuring a photograph by Shuchi Kapoor, March 2020. 13. Mumbai protest against CAA and NPR, featuring a photograph by Anshuka Mahapatra, March 2020.

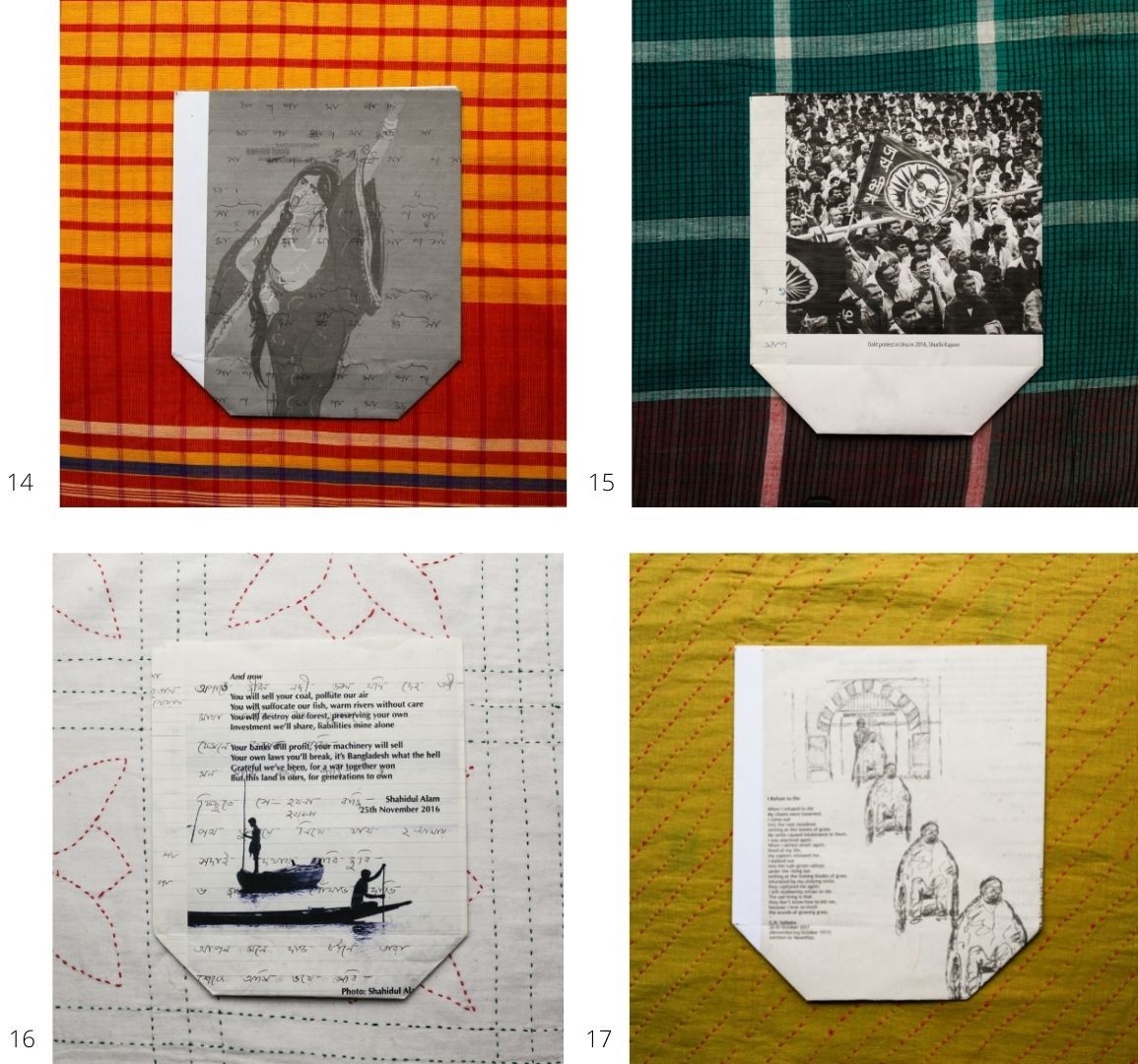

14. Solidarity, featuring artwork by Zehra Doğan, March 2020. 15. Dalit protest in Una, 2016, featuring a photograph by Shuchi Kapoor, March 2020. 16. The Price of Gratitude (reverse), Tribute to murdered student Abrar Fahad, featuring a photograph and poem by Shahidul Alam, February 2020. 17. Free Saibaba, featuring artwork by Lokesh Khodke and poem by Professor Saibaba, July 2020.

18. Chalo Dilli, featuring a photograph by Harsha Vadlamani, March 2020. 19. Release Abul Kalam, featuring a photograph by Abul Kalam, December 2020. 20. Where is Kajol?, made by Sofia Karim’s seven-year-old daughter, Lylah, March 2020. 21. Delhi Pogrom (reverse), featuring artwork by Younus Nomani, March 2020.

VS: Could you share your vision of the future of Turbine Bagh in relation to how it shifts away from elements of preciousness to gain traction in a more global context? And, finally, in what way is this extremely inclusive platform—where multiple voices exist—leaving residues in your personal art and architectural work?

SK: Preciousness is something I do not much fret about because Turbine Bagh has relatively little interaction with the art world. Exhibitions are a drop in the ocean of my wider work. It sprung from the crucible of my home and family. Many of those I work with have become like family members. Most of my day-to-day work involves interaction with lawyers, journalists, activists, human rights organizations and non-establishment artists. I campaign for political prisoners. It is raw, gritty, bleak and keeps me up at night.

The future of Turbine Bagh is unpredictable because it is a movement that shifts with context. Another person is jailed, we start campaigning. A protest breaks out, the artists respond. Turbine Bagh never looks for new work. It never has to. Injustice does not stop, so our work cannot stop. Like the Latin word from which it originates, the turbine is a vortex. It is a device to convert energy into useful work and that is what I hope this project remains.

To conclude I come back to the image. My own medium of the art of dissent is grounded in architecture and Turbine Bagh has influenced that. Lita’s House (2020-ongoing) is an imaginary house for the disappeared, a mirror world of fascism and authoritarianism described through architectural drawings, where the prisoners I campaign for reside.

Model for the BK16 Gardens project (a garden and shelter dedicated to political prisoners), London, UK, May 2021.

Sofia Karim is an artist and architect based in London who explores architecture as a language of struggle and resistance. She re-examines its ideals of silence, truth, beauty and transcendence through this framework. Her activism focuses on human rights across Bangladesh and India and artists’ freedom of expression. She campaigned for the release of imprisoned artists, including Dr Alam and Tania Bruguera. Karim is the Founder of Turbine Bagh, a joint artists’ movement against fascism and authoritarianism. She has staged protest exhibitions at Tate Modern (Turbine Hall). Her work has been presented at Harvard University and exhibited in New York, Delhi, Chicago, Houston and London.

Veeranganakumari Solanki is an independent curator and writer based in India. She was the 2019 Brooks International Research Fellow at Tate Modern in the curatorial and photography department and a resident at the Delfina Foundation. Solanki is currently the Exhibition Design Team Lead for the Kathmandu Triennale 2077, Curator of Future Landing at the Serendipity Virtual Arts Festival and the Programme Director for Space Studio, Vadodara.