Passages: a subcontinental imaginary |

Unsettled Identities

Daily activities of children in the Rohingya refugee camp at Shaheen Bagh. The children of Noor Yunus (a leader of the Rohingya camp) play inside their makeshift home. The community and especially families of children are grateful to certain organizations for the education of young ones. In the beginning, children were unaware of such facilities. Now they are given scholarships by the UNHCR for the hope of a different future. Delhi, India, 9 October 2018, Digital photograph.

Unsettled Identities is a project focusing on lives of Rohingya Muslims, one of the most persecuted and overlooked minorities in the world. There are approximately 900 Rohingya refugees in camps in and around Delhi-NCR alone—spread around the Shaheen Bagh, Madanpur Khadar, Okhla and Vikaspuri areas. This series materialized as I was visiting a friend near Madanpur Khadar, where I would often see men and women from this community.

As my grandparents fled Lahore during Partition, I grew up hearing stories about their exile. I knew how difficult it was for them to rebuild their lives in New Delhi, knowing that a part of them still lived in Lahore. This memory from my childhood and the everyday proximity to Rohingya refugee camps provoked the desire to capture instances of how they were managing to resettle after their forced migration.

India’s biometric verification drive undertaken by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) also coincided with the tracing of Rohingya refugees coming into the country through the North East. The police distributed nationality verification forms to various Rohingya refugee camps in India. These forms were in Burmese and English and the community was apprehensive of them. Instead of filling out the form, many of the refugees wrote in the blank spaces:

“I am not willing to return to Myanmar. Myanmar recognizes us as Rohingya and must restore our citizenship rights. Myanmar must give justice to all Rohingya genocide victims. Or I request the Indian government to resettle us into any third country, rather than deportation to Myanmar, where our lives are not safe.”

One of the leaders of Rohingya refugee camp was concerned about the community as the verification forms brought back memories of the processes orchestrated by Myanmarese government just before driving them out of their homes. In 1982, when the Myanmar Citizenship Law or nationality law was introduced, all those belonging to the Rohingya ethnicity were denied citizenship. Their anxiety was palpable, and all I could do

was listen to them.

They were worried about being sent back. But they were also worried for those who are still in the Rakhine state, as they were forced to share information about their relatives in the verification form. Every morning, the families would listen to the latest news of Rohingya communities in neighbouring countries, in anticipation of the worst.

The Rohingya in Delhi are still being periodically relocated. They continue to be haunted by fear, memories of persecution and lives long lost, while being forgotten by the world. No matter how hard they try to rebuild their lives against great odds in a city that is new to them, they are in one way or another reminded of their position as outsiders.

These photographs capture glimpses of friendship, care and community that I shared with them. My work attempts to acknowledge and engage with complicated questions about identity, statelessness and belonging. I wish to explore the multifaceted nature of a Rohingya Muslim resettlement while remaining fully conscious of the political circumstances it emerges from. But more importantly, I am trying to get close to this community and observe their lives from a human perspective. In my photographs, I have been trying to capture moments and emotions that connect us and tie us together as human beings. A doting father, a caring mother, a scolding uncle, a fighting sibling—every emotion or reaction I have observed here reminds me of my own home. Yet, I am also able to now understand how claustrophobic it can be to spend years under a tarpaulin roof built on top of cardboard walls. I can imagine how uncertain your future can be if, legally, you belong to no country. Every day spent here, with them, is a realization that there is so much more that I am yet to observe, experience and learn.

Children being playful at Khajoori Khas, another refugee settlement where families live in concrete rooms. Delhi, India, 28 October 2018, Digital photograph.

Anwara Begum combs her daughter’s hair before she leaves for school. The children here study at Gyandeep Vidya Mandir School near Shaheen Bagh. The Zakat Foundation has played a key role in helping children go to school so that they do not lose their potential due to the forced cross-border migration. Delhi, India, 23 October 2018, Digital photograph.

Rohingya refugee camp near Shaheen Bagh. Rohingya refugee camps across Delhi lack basic amenities like potable water and sanitation. Despite these unhealthy living conditions, most Rohingya prefer living here over the life they had back in Myanmar. Delhi, India, 6 November 2018, Digital photograph.

Mohammad Faruq, a daily-wage worker in Khajoori Khas, spends time with his children. Delhi, India, 9 October 2018, Digital photograph.

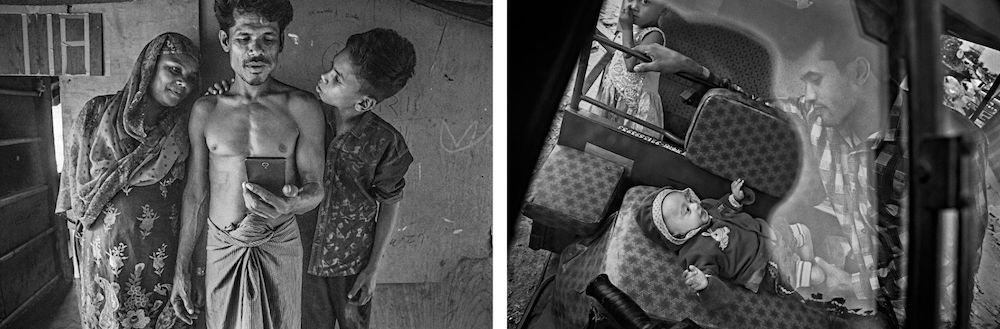

Left: Mohammad Ismail and his family on a video call with their daughter, who lives near Cox Bazaar in Bangladesh. Delhi, India, 18 October 2018, Digital photograph. Right: Rahmathullah, with his son, can be seen through a window of his autorickshaw in Shaheen Bagh. Delhi, India, 20 October, 2018, Digital photograph.

A young Rohingya man passes the ball to his teammates during a football match with another Rohingya team from Jammu. Their team is called Rohingya FC and has participated in numerous football tournaments in the past. Ali Johar, a young community leader, said: “Football has given us positive exposure and enabled us to tell the world that we are just like them—we are normal human beings. We have also got the chance to make many new Indian friends. Football has paved the way for constructive change, but sustaining the momentum is proving to be a challenge.” Delhi, India, 3 October 2018, Digital photograph.

A child rests inside the camp. Due to the disease-prone living conditions and lack of sanitation, children keep falling sick and most of them often suffer from diarrhea. Delhi, India, 12 October 2018, Digital photograph.

Identity card of Shaheeda Begum, with a family photograph, placed on a prayer rug. When the military regime took power through a coup, they started verifying identity documents to start the process of deportation of this community from their own homeland. Delhi, India, 20 September 2018, Digital photograph.

Photographed outside his home, the grandson of Dil Mohammad (a leader of the camp) wears an army costume on Eid-ul-adha. Delhi, 22 August 2018, Digital photograph.

Anuj Arora is an independent photographer based in India. He studied visual communication and worked as an Associate Visual Designer in Delhi before moving to photography. Arora was mentored by Bharat Choudhary at Sri Aurobindo Centre for Arts and Communication in New Delhi, where he pursued documentary photography. His work has been exhibited by Prameya Art Foundation as part of PRAF Discover and he was a finalist of TOTO Photography Award 2020. He won third place in POY Asia in the Covid Expressions category for his work Portrait of My Mother. He was one of the participants of Missouri Photo Workshop Hometown Edition 2021. Arora has been documenting issues of migration in Delhi as a long-term project.