Ode to the Home (Screen): Notes from an obscure computer history

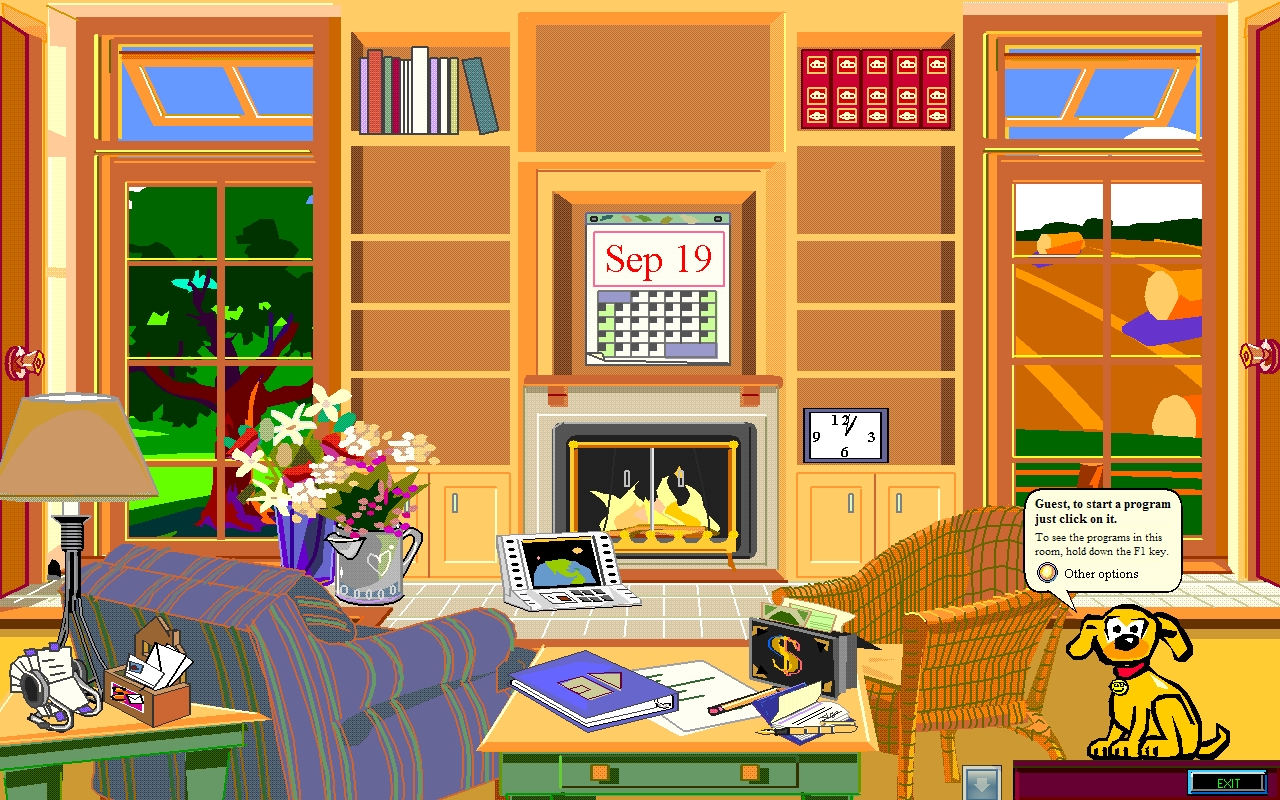

Screenshot of MS Bob Interface, Home Screen. 2019. Screenshot by author.

“MS Bob” was an early experimental software product released by Microsoft in 1995, and discontinued about a year later. As Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) – like the Windows Operating System were fairly new and unfamiliar to users, this program was designed to create an alternative environment or “interface landscape” through which to access programs on the personal computer. Microsoft Bob presented screens showing a “house,” with “rooms” that the user could go to, containing familiar objects corresponding to computer applications, for instance, a desk with pen and paper, a check book, and other similar items. Each object, when clicked upon, would open up the relevant program it symbolised. There were also a range of “decorative” objects on this interface, which could be customised and positioned in the room according to the users’ preference. The general idea was to acquaint the novice computer user to the way its programs operated – it was designed to be akin to the process of moving into a new house. MS Bob also came with a variety of animal cartoon characters which would guide the user through specific programs and together, they formed a kind of family or community of helpers for the user.

This program was, for many practical reasons – a failure. The cartoon characters, animation style, and loud sounds made it an uncomfortable product for professional environments, and the animal assistants, with their incessant pop-up messages and instructions were often felt to be a nuisance. Microsoft and the world moved on from this hiccup in interface design to adopt the slick, flat interfaces of today. However, we continue to make sense of the digital world largely through a similar strategy of symbolisms and gestures which has come to define how popular human computer interaction looks like. These gestures, concepts, and visuals of the contemporary interface, refer to foundational imaginations of what the personal computer is/was and what it was for. Skeuomorphic design is a strategy especially used in interface design through which novel concepts are represented with older symbols fulfilling the same, or similar functions – the most common examples for this include the windows software “sticky notes” which looks like a physical notepad.

This metaphor of the computer screen representing physical “space” perhaps began when digital space became “navigable” by a cursor or pointer. In essence, this early GUI innovation transformed the subjective will of the computer user into a virtual icon or “avatar” that moved in a fictional space on their behalf. While these fictional spaces drew from the spaces in our “real world,” the rules that governed it were quite different. The dimensions of virtual space are visible to the user through their conceptual representations on the interface, as opposed to the dimensions which are tangible and perceived by the senses and cognition.

A key conceptual idea dominating the interface today is that of the desktop – an interface landscape slightly different from the ‘home’ of MS Bob. The desktop is a place of work – a specific kind of work which does not directly involve manual labour in the physical world. The desktop is also a surface, an inherently two-dimensional plane which serves as a background for other activities. The surface of the desk in both worlds – is customisable, with photographs, notes, and personal items being placed on it by the user.

The following images are custom-made desktop wallpapers found from various sources on the internet. These curious images manifest the spatial metaphor of the desktop by converting the flat surface of the screen into a three dimensional scenery. This is done by all desktop backgrounds, but these specific models of indoor spaces create a conversation between the “background” of the image and the “foreground” of the interface (the icons on the home screen) – blurring these boundaries to create a unified sense of space within the computer screen.

3D Desktop Wallpaper found on Pinterest. 2018.

Shelves Desktop Wallpaper found on getwallpapers.com. 2018.

These 3D visualisations of interior spaces are constructed images, which reveal multiple perspective points on closer viewing; each element in these constructed landscapes – the desk, the shelves, the textures have been drawn from a repository of models to be collaged together digitally. This is what lends them a surreal quality – a kind of impossibility that is brought to life in an attempt to mimic the ideals of perspective drawing. They embody a naive humanist “gaze,” and a desire and nostalgia for the stability of traditional, formalised spaces as the forefather of the desktop.

These “desktop background” images can be found and customised on many popular stock image websites. As such, they often contain empty frames for the insertion of images, shelves, and pin-up boards to place other custom items on and ways to modify the wallpaper and other features of the space. While created for modern, minimalistic interfaces, these pseudo-realistic images remind us of MS Bob, constructing impossible homes inside the interface.

Office Desk Wallpaper found on getwallpapers.com. 2018.

Much like the home from MS Bob, these endlessly customisable flat surfaces work to create the illusion of depth and shelter. In doing so, they establish and highlight the idea of residence embedded in the human-computer relationship that is constructed by the interface. For most of us today, the computer is not just a complex machine to assist in processing tasks; it acts as a space of work and leisure so much so that switching to a new operating system is referred to as “migration.” Much like many mass-produced items, personal computers grow to become personal to their specific users. However, while other products and devices might only provide their physical surfaces for this personalisation, the personal computer, and interface-based machines in general, open up an endlessly expansive surface onto which its users may project themselves.

This is my coworkers desktop, found on reditt.com. 2018.

This process of domestication and inhabiting runs in the background of the “real” things computers are for – the multitudes of applications running on the machine. Much like, and perhaps naively represented by these desktop backgrounds, it is these processes that slowly come to define our collective relationship with machines and technology at large. The idea of software migration perhaps echoes the multiple anxieties of the interface paradigm we live with today. More and more, one’s choice of OS is a part of their identity markers (the infamous mac vs. windows feud).

The interface seems to occupy a dual space of language and geography within the digital world, migration from which momentarily throws the user into the deep end of an unknown land.

A pertinent question emerges from considering these tensions between the home screen and the desktop. While we are increasingly encouraged to occupy the machine as one, how does one reconcile a commercial product as one’s home? This question pokes at the aesthetics of the contemporary interface and the way it standardises our collective imaginations of digital space. Rather quaintly, many customisations made to the flat, professional aesthetics attempt to redefine digital space, subverting the interface as a mass service to make it specific to the individuality of its user. While these desktop backgrounds emerge as anomalies, and are only relevant in obscure groups on the internet, they present an example of how we might multiply our imaginations of the interface, and stay with metaphors that might encourage our computers to be more personal.

Anisha Baid is an artist and writer based in Bangalore, India. Her practice and research involve an investigation of pervasive technologies through an examination of their design, diversity of use, and their relationship with ideas from science fiction. Her work tries to decode computer labour through the interface – a technological tool that has converted most spaces of work into image space.

[Editorial Inclusion]