The Armenians

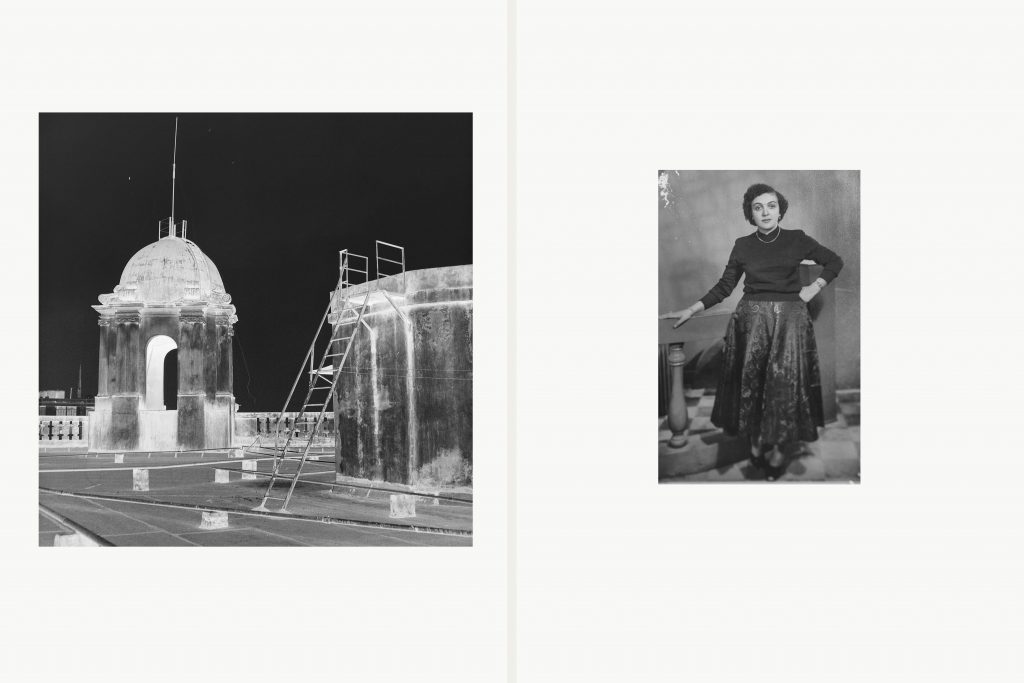

Hold Nothing Dear is a reverie on the Armenian community of Calcutta. What started off as a documentary project, is now a historical, conceptual, allegorical photo book that looks at the idea of attachment that the now near-invisible community has to its glorious past. The book is in three chapters: Book of Attachment, Book of Time, and Book of Detachment. It includes photographs, negatives, archival imagery, and text. The Armenians may be considered the founders of modern Calcutta and the few that remain have become the gatekeepers and consolidators of this vast history and held on to their past with pride.

- You have been immersed in the project for nine long years. What are the personal challenges that you have faced while covering the lives of Calcutta’s minority community so intensely, especially one that has roots that go as far as the 15th century and Akbar’s court, or even earlier to 400 BC?

In the city today, the community is invisible, literally and metaphorically. But their imprint remains, hidden behind layers of neglect, forgetting, and erasure.

When I started out, the challenge was access. The community is guarded about their privacy… rightfully so. It took me some time to gain the trust of the people I wanted to photograph. Over time, some of them became collaborators and overall the community has been very supportive.

The larger challenge really has been the lacuna of information and research material. This is a community that was alive and thriving, business-wise and culturally. Post-Independence they started to leave after being in Bengal for over four hundred years. In comparison to this vast history, the material on them in Calcutta (Kolkata) is very hard to come by. I found some scattered material at the Asiatic Society, some at the Armenian school library and church, and the rest from journals, some books, and oral history.

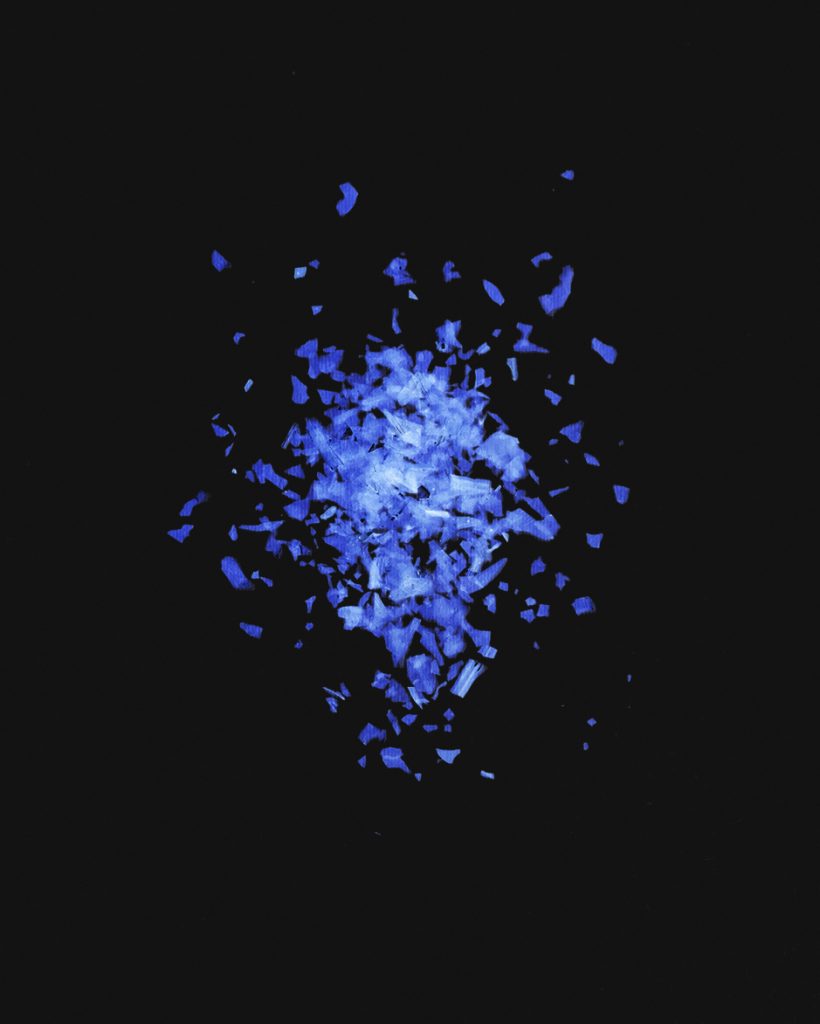

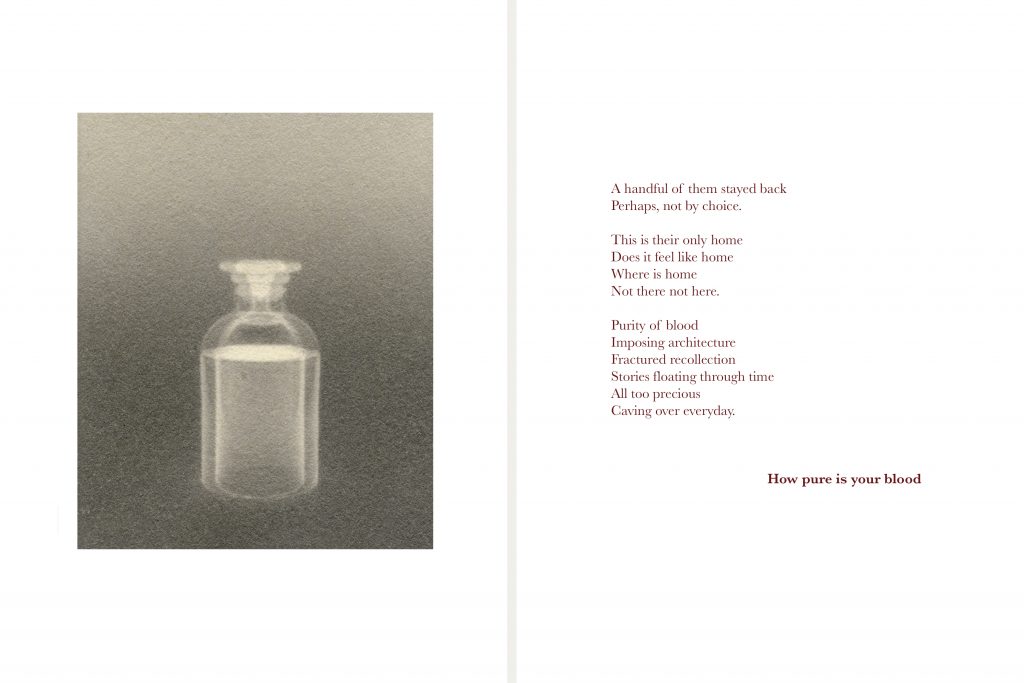

This was the greatest challenge but has become the pivot of the work. This absence becoming part of the process. That led to looking into materials and other traces –like shellac in which they traded, a substance that can burn down without a trace; blood and the purity and sanctity of it; and architecture.

- You have been documenting a people/community who are on the verge of extinction in the only habitat that was ever known to them. In your opinion, what historical/archival importance does your book hold with regard to that?

This is not the only habitat they have known historically. They are a diasporic community, most of them twice removed. They came from Isfahan, Tehran, Julfa, Rangoon, Jerusalem, Baghdad, and some also from Yerevan. When they came, they brought their collective histories with them, and some never went back. They came much before the British, and could be considered the “founders” of modern Calcutta. They were the “stepping stones” for the British. This book presents this evidence and so will be an important historical and archival source. By presenting an alternate history, while refraining from being empirical. I hope this book can honour the invaluable contributions made by this unique community.

- Do you see any change in your perspective as to how you will approach future stories after covering the Armenian Community? How different has this body of work been for you than your other works?

This work has been very different from everything else I have done in the past. To be fair, the years of work that went into it has something to do with that and its evolution into a book. I can ascribe a lot of what I have learnt about photography to this book. The fact that photos are central to the book, yet the work hinges not on photography alone. There is a lot more happening. A constant subtext, a subliminal layer that goes beyond the photos and what you see. Hitherto unseen archival material as well as text written by me and taken from others lend a texture that is quite unique. And yes, I think I can say this work has changed me, and I will take that forward into my other works.

- While working on the project, what were the ethical boundaries that you created for yourself? And what were the parameters for you to arrive at those?

In the beginning, I documented the community for over three years. Then there came a time when those documentary photos just didn’t make sense to me anymore because a pure documentary approach was not doing any justice to the community, the collective history or the spirit. I started again.

I took a step back to re-train my eyes and see their world not through an exotic lens. It is a question of representation. It is a thin line, but a pertinent one. There is so much grace and dignity the community exudes. There is nostalgia of what was, sadness at having lost so much, and a quiet yet firm will to hold on to their Armenian roots. I knew all this had to come through in the work.

It is for this kind of representation that the work has taken so long to complete. I was careful not to rush things, but to let the work reveal itself to me. I think that has happened. When I made the dummy book with a generous grant from the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA), the next step I envisioned was to publish the book. But I went back to the drawing board, because I felt there was something more that could be done. Now it is almost complete and I think it will give a true sense of this small yet very significant community that helped build Calcutta.

- How important is “vernacular photography” today? What concerns did the community share with you when being documented?

It is perhaps the most important documentation. Most of the archival images I have used in the book are from the community. I am so thankful they allowed me to use them. From family albums, journals, and framed photos too. I’m pretty sure they have not been seen before outside the community.

I think they were concerned about the question of representation in the initial days. But eventually it became a collaboration, and now they are happy with the book.

Note: This will be a self published book to be printed and produced in Calcutta.

Alakananda Nag is a visual artist based in Goa. Her works involve photographs, archival matter, object, and text. She graduated in Documentary Photography & Photojournalism from the International Center of Photography, New York. She has been working on the Armenian community of Calcutta for over seven years. https://alakanandanag.com

Interview with Zainab Mufti.

[Editorial Inclusion]