The work exhibited by the 47 artists from India presented as a part of FotoFest2018, is all created in the 21st century, which, as Zahid R. Chaudhury points out in his article, ‘Life and Death under Neoliberalism’, “…has witnessed the passing of post-independence Nehruvian dreams of a secular nation and the continued success of right-wind religious populism…that seems comfortable at home with ongoing liberalisation.

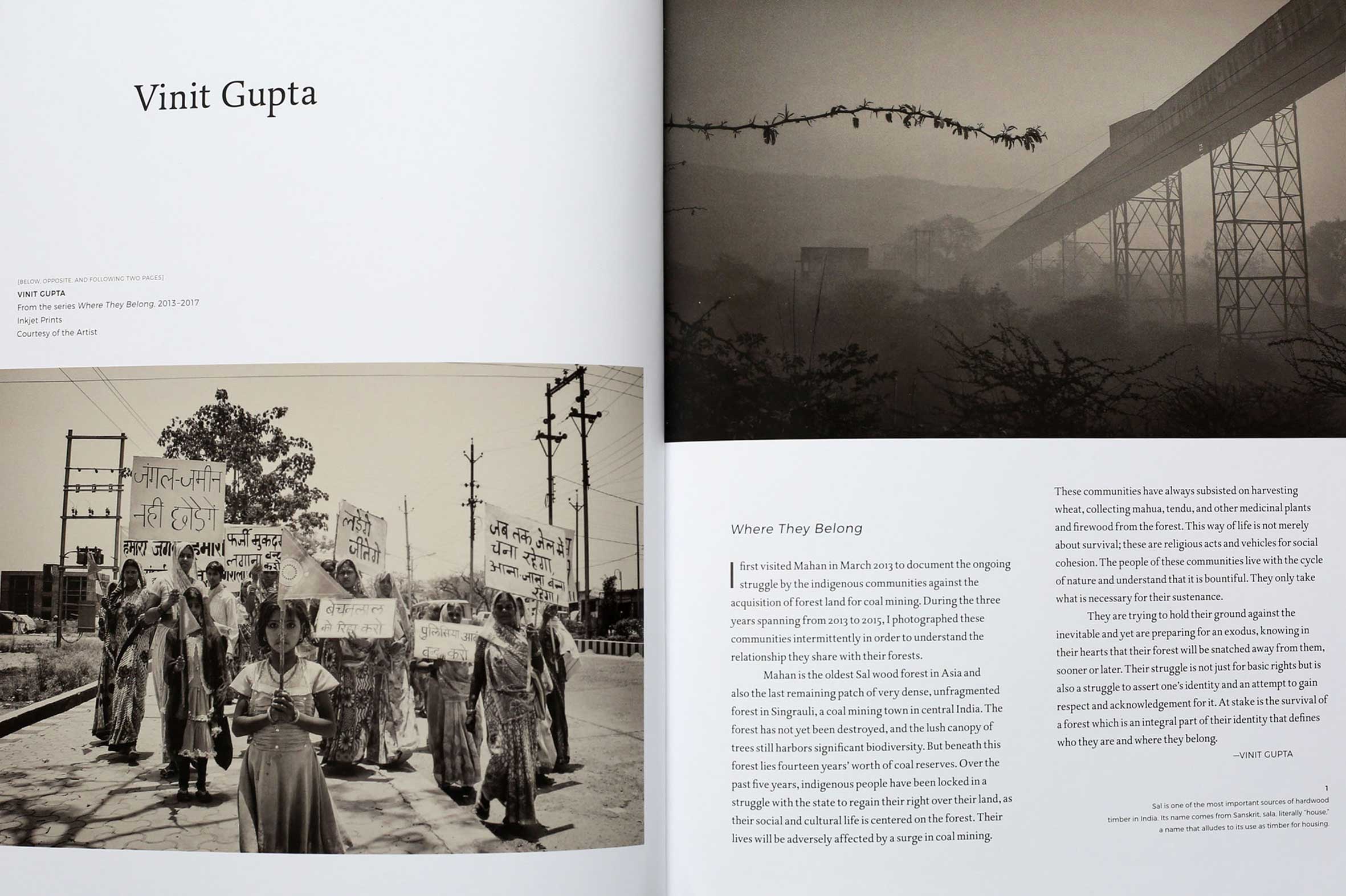

Citing the contributions of practitioners such as, Nandinni Valli Muthiah, Vinit Gupta and Chandan Gomes, he talks about how the contemporaneity of the exhibition is marked by its presentation of the material realities [of India’s history] through a variety of ‘aesthetic registers’ including allegory, documentary and scientificity.

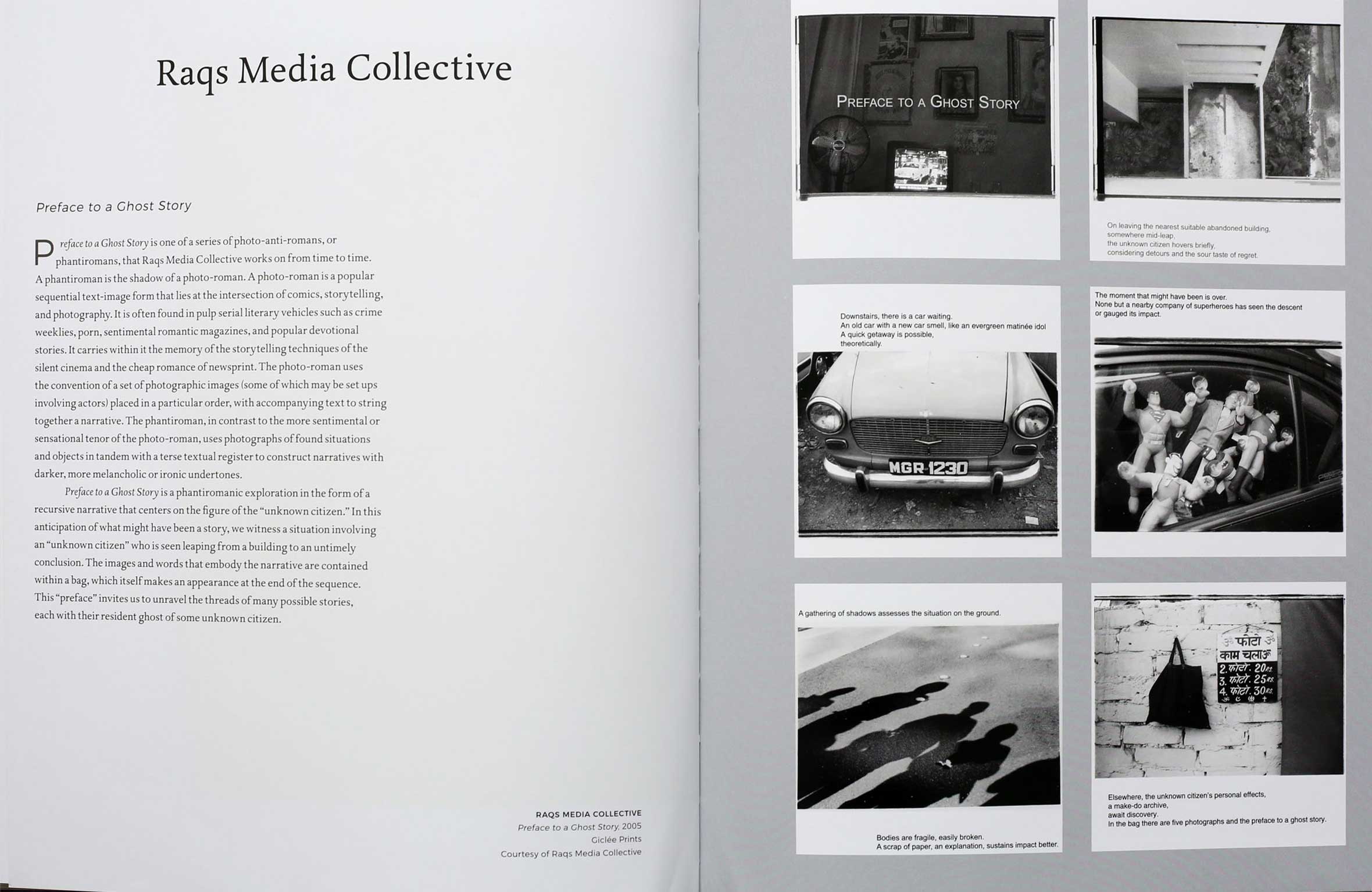

Spread from INDIA/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art

Spread from INDIA/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art

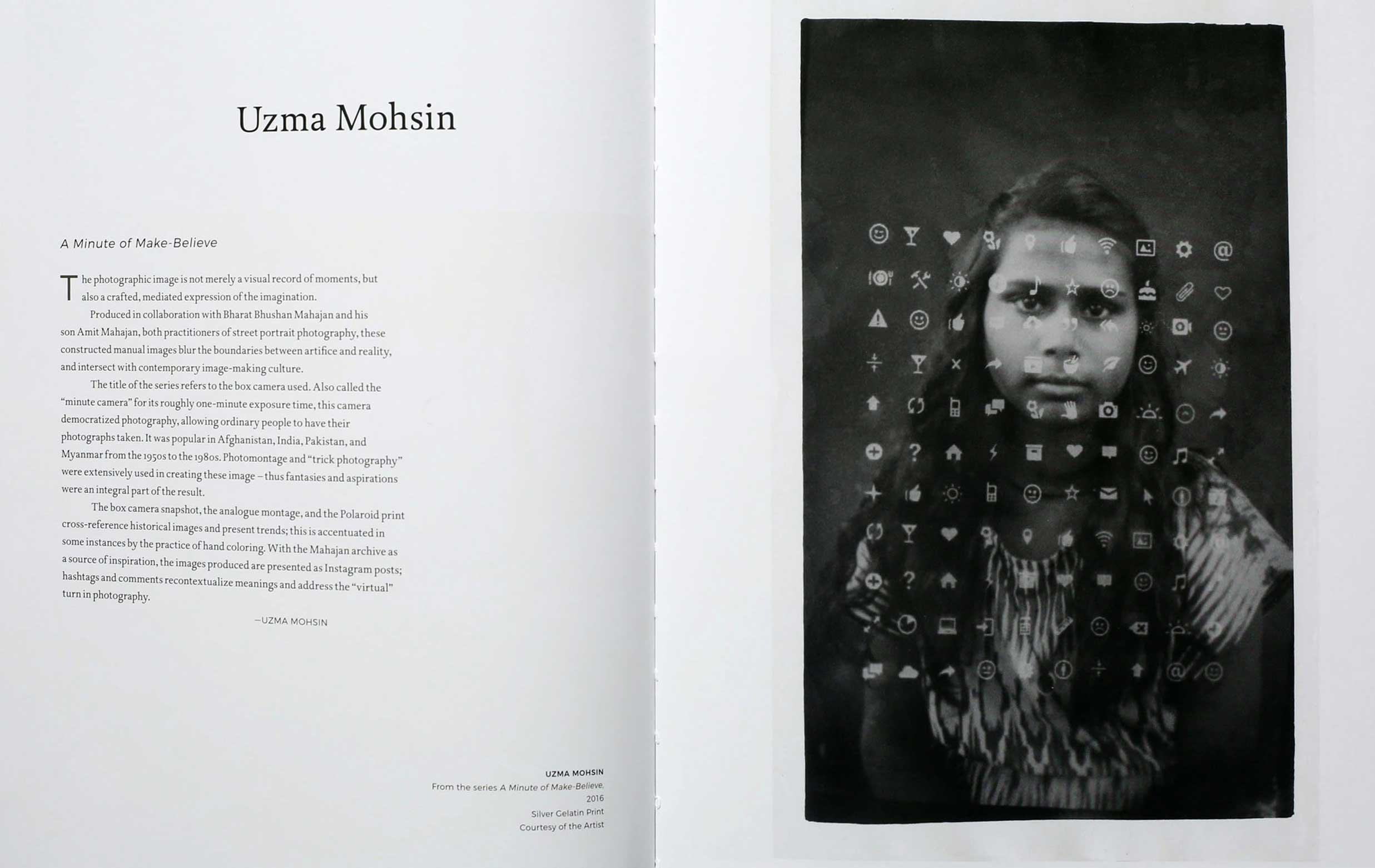

Talking specifically about how the exhibitions present the innate complexities of identity, another author asks ‘What role did the camera play in producing individual self-expression?’ Nada Raza of the Tate Modern, in her piece titled Iconicity and Mimesis in South Asian photography, looks into the role of the alter ego, specifically highlighting the curatorial selection of staged portraits which employ the stylistic motifs of impersonation and re-creation to represent duplicities and streams of consciousness around the notion of the self as a visibly mutable subject, and one innately drawn to change.

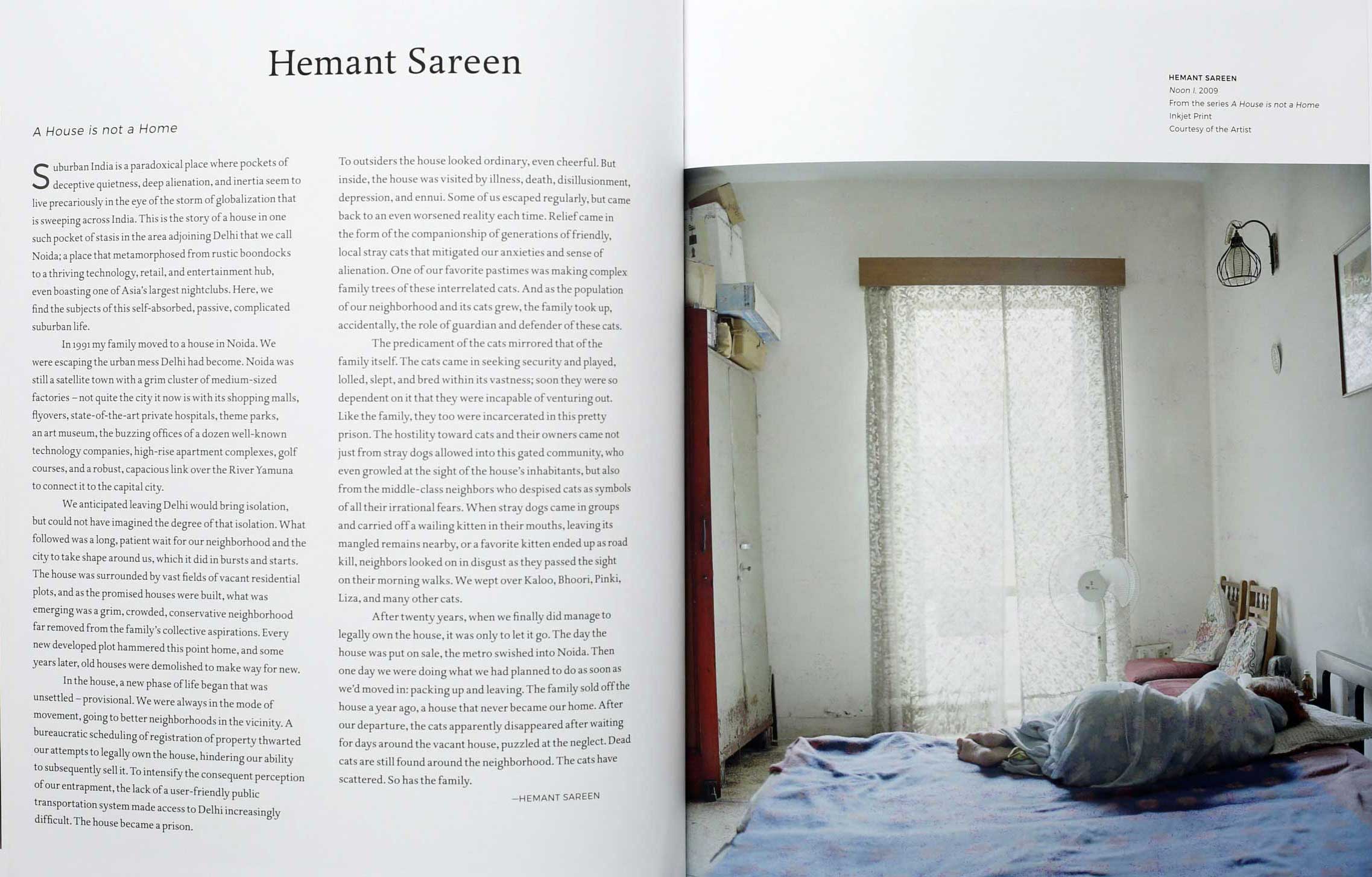

Spreads from INDIA/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art

Spreads from INDIA/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art

This week, continuing our discussions with Sunil Gupta, lead curator of the recent exhibition INDIA/ Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art, we discuss some more ideas and background experiences that steered his curatorial approach; including the importance of an activated public sector in supporting the arts and some future prospects of photographic practice in India.

RA: Can you speak about the reception of the exhibition during FotoFest 2018? How was photography from India received in the United States?

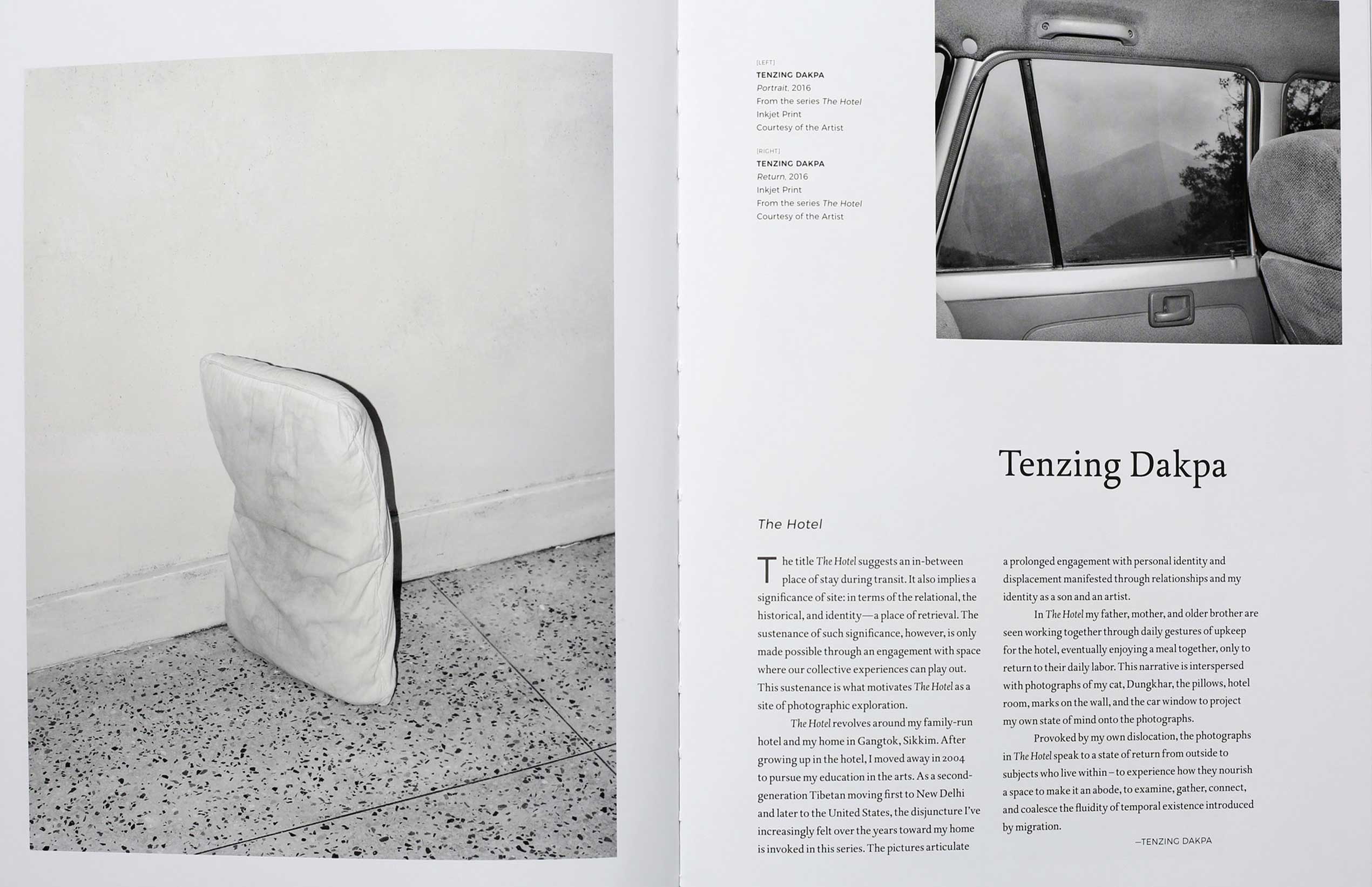

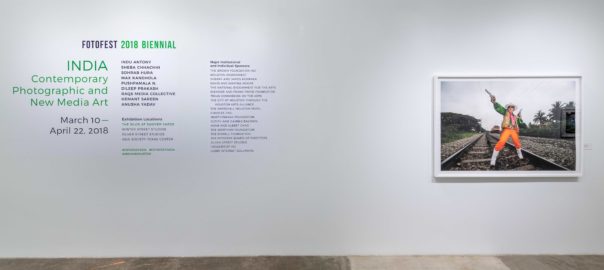

Indu Antony, Manifest at the FotoFest 2018 Biennial

Indu Antony, Manifest at the FotoFest 2018 Biennial

SG: [From the last interview] …In addition, looking back on the exhibition now, it seems to me that the exhibition was a very big success in the sense that it fulfilled many of the requirements of photography—the diversity of approaches and techniques; the diversity of gender. There was almost an equal balance in terms of women and men, and I think there was a big diversity of age too.

And there was a huge range of, what in the West, people regard as a kind of critical practice—an almost academic practice without the ‘academy’. So that was interesting because, you know, we’re short of academies in India.

So I think the Americans found that quite engaging. Their audiences, unlike an audience in the UK, are less informed about contemporary India and therefore more intrigued ideas generating from it. Hence, I think, as a historical moment, it feels like this was the right time for the exhibition. If we had done it 10 years ago, it might’ve been a shade too early and 20 years ago would have been far too early. But as we know from the Western art world – after China – the next region of interest was India. An interest that may or may not be on the wane now, but commercially, it has woken up.

Spreads from INDIA/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art

Spreads from INDIA/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art

One of the markers of success for people looking at the exhibition was, of course, that there were sales. The auction that was held had about 15 works from the exhibiting Indian artists, which eventually sold!—for hundreds and sometimes, well over a thousand dollars. And I think this tangible exposure to the marketplace was an eye opener especially for the Indians who were present at the auction dinner.

I know that there are a number of American museums that are looking to acquiring works of Indian lens-based artists having seen this Biennial; because the thing is, America is a full of local museums and hardly any have an ‘Indian’ photography collection. And I think this could be a beginning—that some are seeing this as an opportune moment to step in and start making some acquisitions. But they’re also looking at it with critical eyes—which of these works is going to have any longevity? Which pictures should and can serve a museum’s purpose as the basis for a collection that might grow in time?

So what kinds of works are they buying from this project(?), you could ask. They like the experimental, but they also like classic photography – even large format landscapes. And I think Americans prefer to collect photography more than the British do. The British like their text-based arts too much.

I’m in the wrong place!

Also, the media response was phenomenal. It was in the New York Times, the Washington Post and in the Guardian [in the UK]. And it was also picked up by all kinds of regional press. So I think by those kind of press markers it was also a success, but I always find it hard to judge this success. However, I did have a feeling about this one—it was a bit like Where Three Dreams Cross which was also a benchmark for the Whitechapel Gallery, because the exhibition, which was ticketed, was packed all the time, and the catalogue was sold out a couple of weeks before the show was over!

So the question now is, I guess, what’s next….?

RA: Another exhibition that you highlight in the publication [INDIA/ Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art] is Click! that took place in 2008. What sort of challenges did you encounter with India being placed within a sub-continental sphere and in volunteering new voices?

Opening night of the Click! exhibition (2008)

Opening night of the Click! exhibition (2008)

SG: This whole idea of ‘who’s in’ and ‘who’s out’ of the exhibitions, who gets to select and how does it get selected and all of that…is all apparently a mystery! I once met a French collector in Paris and it was very clear to him—it was just about ‘good taste’ and that’s how he justified what he bought which was basically what he liked and as a very wealthy man and a patron, that’s how he set the tone for things. I think we shouldn’t forget that some ‘good’ also comes from that kind of patronage.

So, I’ve come to the conclusion—‘good’ is not a word that I personally like to use because who’s to say what’s good? It’s so subjective. It rather became more a question of which practices are more successfully trying to say something new or different with the project; and which ones then work better in conversation, because, as the organiser of group shows, there are other criteria—how does it sit with something next to it in the space, as you have to think about all four walls collectively.

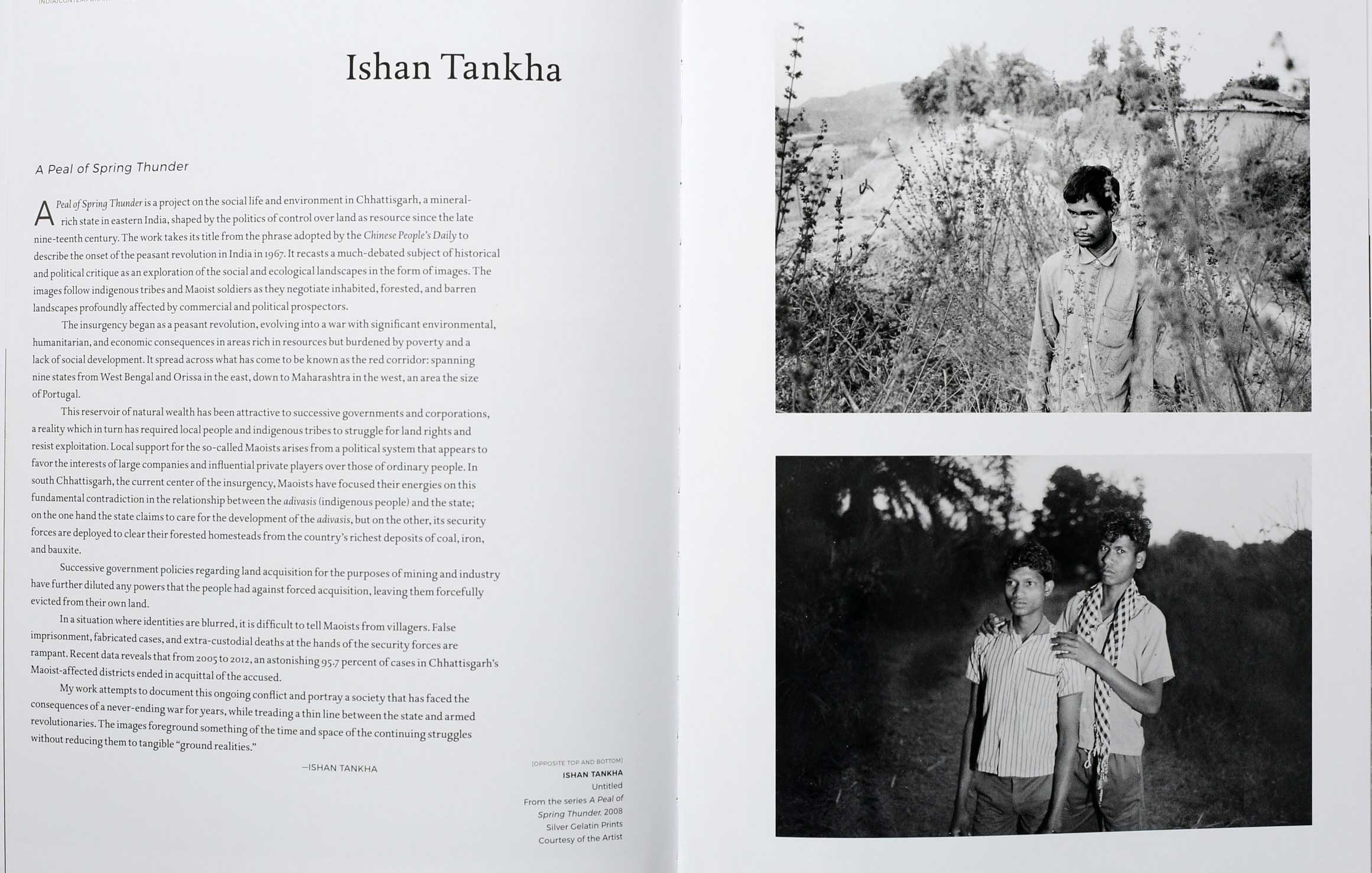

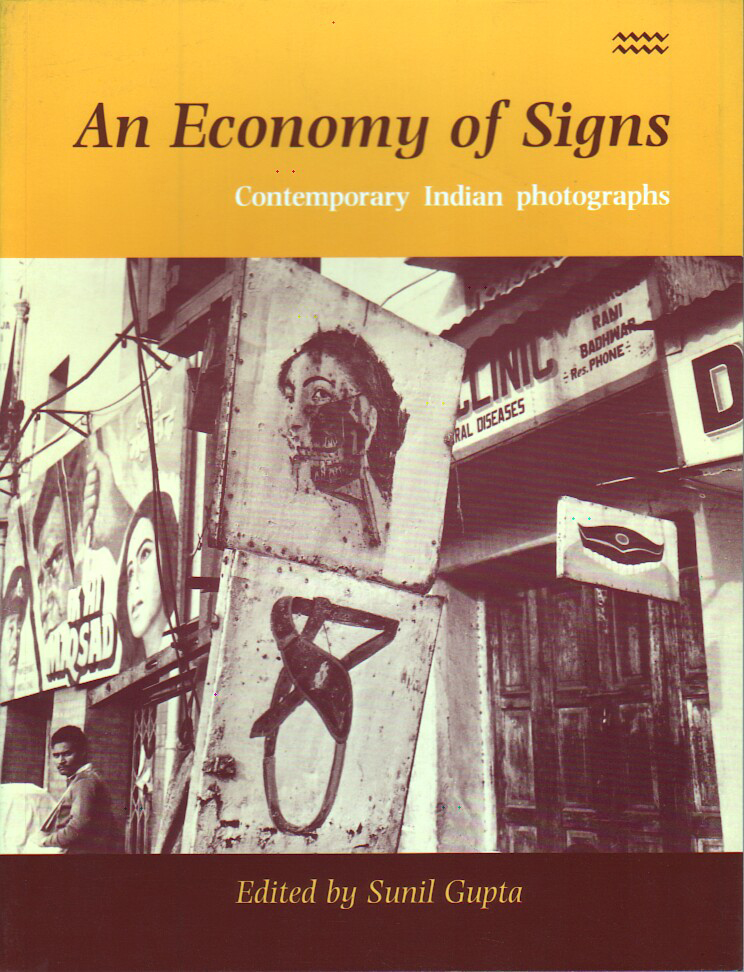

As for the exhibitions, I’ll step back to an earlier show which is from 1990—An Economy of Signs, which was the first time I researched a group-show out of India, that was held at the Photographers’ Gallery[London], and with this one we actually had a budget to commission new works! I was trying to make a point. I was trying to prove to the London audience here [at the Photographers’ Gallery] that if you commissioned eight Indians from India, they would give you quality work of an international standard—something the institutions were not really convinced about In the beginning.

Publication released with the exhibition Economy of Signs (1990)

Publication released with the exhibition Economy of Signs (1990)

Autograph newsletter on Economy of Signs (1990)

Autograph newsletter on Economy of Signs (1990)

So, we had eight artists—four were women and four were men. And that’s when I met Radhika Singh. At that time, in 1988, there was no primary research or much published material at all. So I’d fly into Delhi from London because that’s my hometown – a smattering of people and places that I knew of like Triveni Kala Sangam – venues from the sixties and seventies.

And then someone said that Radhika runs a Photo Agency, which seemed like a very remarkable thing at the time, because there weren’t any that I had come across before and so, through her photographers and then from one person to the next… is how we found artists.

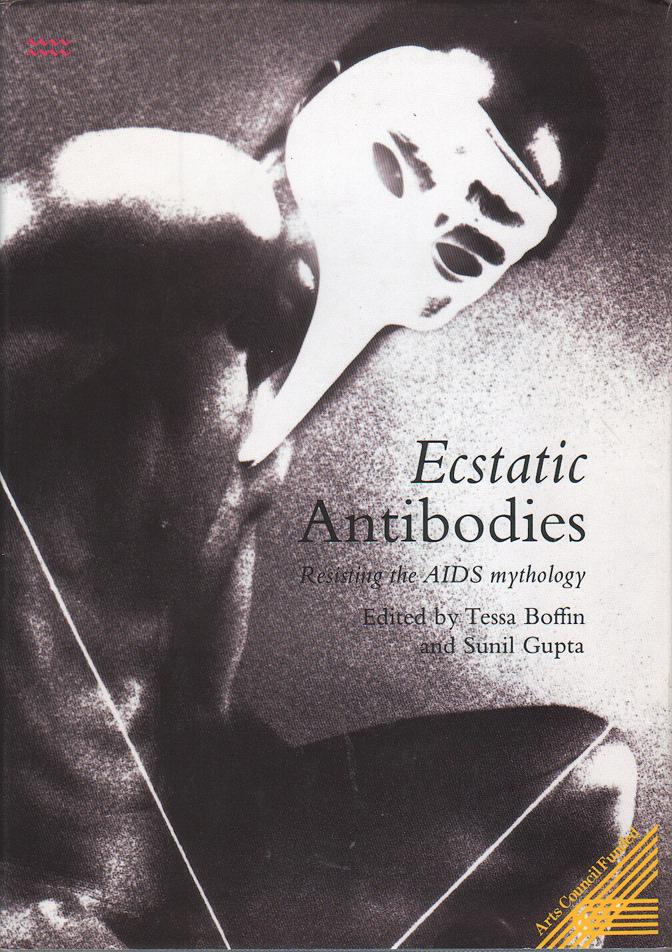

Publication released with Ecstatic Antibodies (1990), an independent curatorial project by Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta about AIDS and representation in Britain.

Publication released with Ecstatic Antibodies (1990), an independent curatorial project by Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta about AIDS and representation in Britain.

But that was 1988, and between 1988 to 1990, when I researched An Economy of Signs was also when I was working with a group of people to found Autograph, and we had its first show, which was called Autoportraits. I left my teaching job to take up curating, because when we started INIVA (Institute of International Visual Art, London) in the early nineties, I became one of the franchisee curators with a photography show called Disrupted Borders, that opened in 1993 as a collaboration between my company – OVA (Organization for Visual Arts)– and Arnolfini (Bristol) as well as The Photographers’ Gallery, London.

And one of the other things I’ve liked to do in my curating career is to not always look for the ‘newest’ and the ‘latest’, but to see who you can carry to the next level—who’s got the longer potential? So I took Sheba Chachchi out of the Indian context and put her into Disrupted Borders along with 12 international artists.

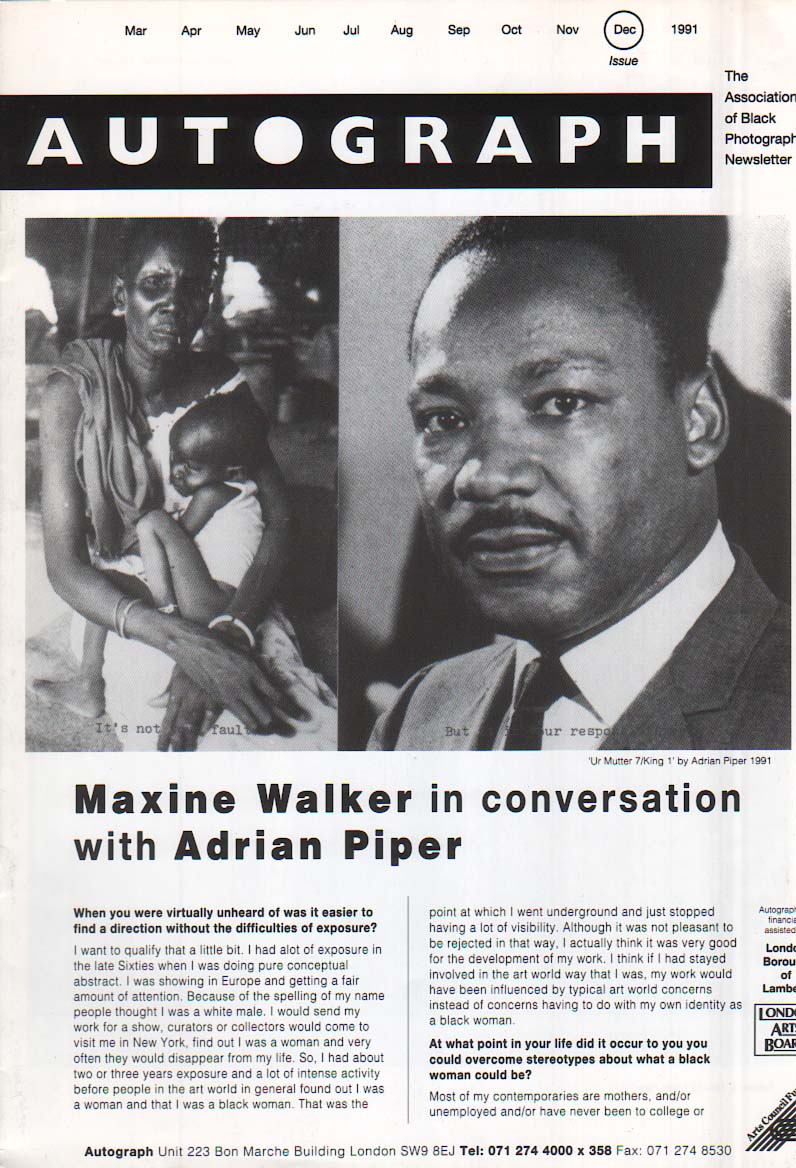

Autograph newsletter, 1991

Autograph newsletter, 1991

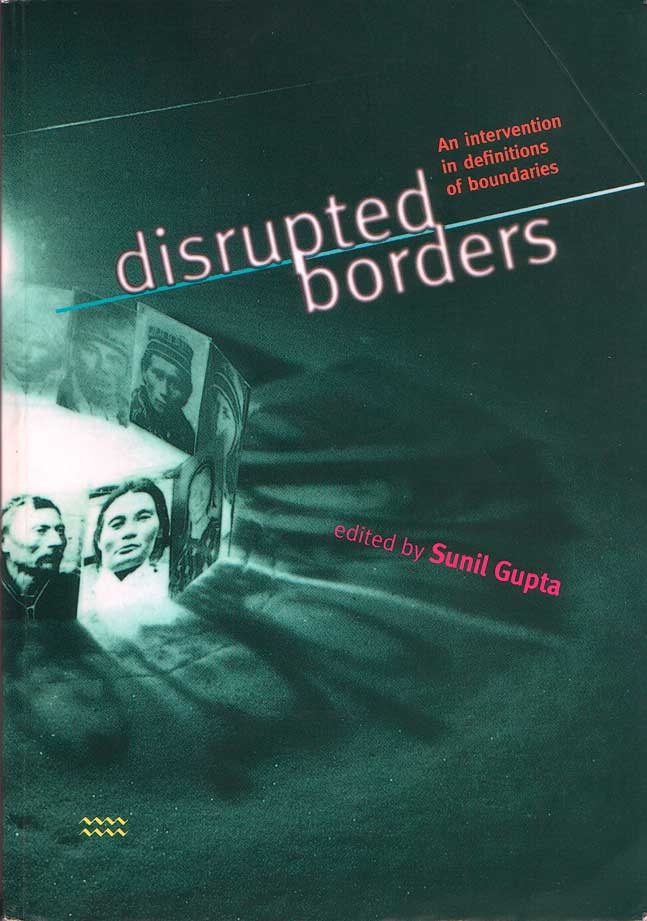

Publication released with Disrupted Borders (1993)

Publication released with Disrupted Borders (1993)

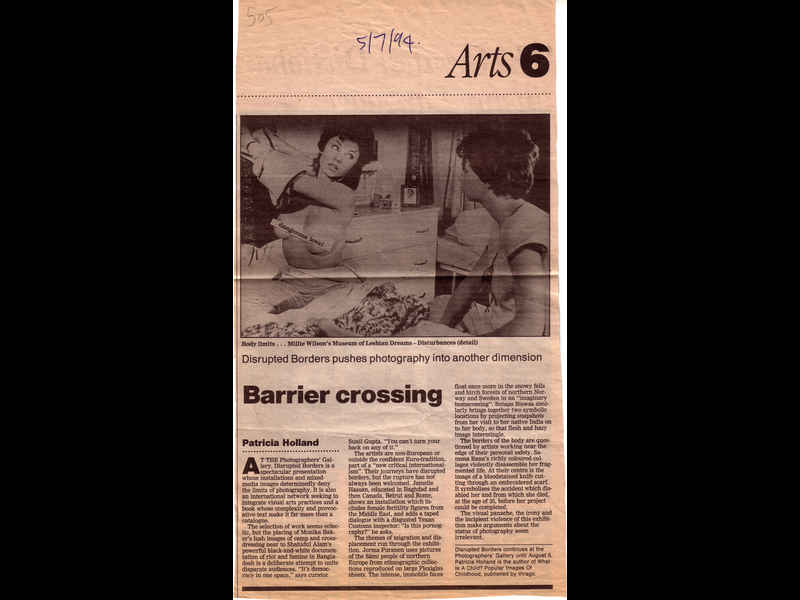

Review of Disrupted Borders in The Guardian (1994)

Review of Disrupted Borders in The Guardian (1994)

So Sheba became my connecting thread and she’s been in all of the exhibitions, so in a way she’s disproved her male critics from 1988 who told me that she was not a photographer.

But also, one the pressures of curating is that you’ve, infact, got to find something new; either a practitioner, or the work. I went for this entertaining curators’ tour once in 1994 as a preamble to the Johannesburg Biennial. I was representing the UK (1995) and they gave us an art tour of the country. Because of the cultural boycott of South Africa and it’s apartheid regime, very little was known outside about it’s contemporary art practices. The organisers in South Africa took a number of us on a three week tour of the country, in order to introduce us to collections and artists. In return, we agreed to feature one of their artists in our country shows. I featured the artist, Clive Van Den Berg who made spectacular fire drawings on mine dumps. So there were 50 or 60 curators from across the globe and we would all come out of a bus and fan out to discover the ‘new thing’! An authentic African artist behind a bush! And we were in competition—I had to find something better than you and that meant beating you in a race to discover the artist. So that was an interesting exercise. This kind of searching does go on to a certain extent.

Discussion paper for the development of photography in Britain commissioned by the Arts Council and the Minority Arts Advisory Service

Discussion paper for the development of photography in Britain commissioned by the Arts Council and the Minority Arts Advisory Service

So returning to Click!, only some of the artists had stopped practicing and were no longer involved in photography and therefore couldn’t be in that show which was ‘contemporary’, in relation to that present time—people like Sanjeev Saith, because he’d become a publisher and less of a photographer, were not especially represented, although I think we did manage to get a picture of his father from him.

So Click! was a big exercise in the sense that I made a lot of time commitment to researching it. And we (Radhika Singh and I) had an important conversation with Vadhera Art Gallery to see if they would commission the research because they were used to the idea that artists came with ready-made work in order to exhibit. So research did not enter the picture and I was saying if there’s no research, there’s no exhibition. This was a bit of a stumbling block because that was not the way things worked in the private sector and there was no accessible public sector to support it either. So finally, they agreed to fund some research.

We’d send out word before travelling to different cities—that we were going to be there to select work of as many people as possible. This was done through word of mouth and local networks. People came and some sent in CDs. And it became a very complicated exercise because photographers would come in and didn’t know how to present their work! There was a two way communication gap—people coming with too much work, the wrong work, asking you what genre you were looking for because the whole exercise seemed like a new experience; and us trying to explain what we meant by a ‘portfolio review’. But we persevered, and we saw several hundred people and looked at twice as many via their CDs that were just posted out. And in time, this research became part of the larger project of WTDC—for more contemporary works.

With Click!, we were trying to include as many artists possible. We only had one or two pictures per person—it wasn’t about the practice, it was like we wanted to show how many people were making photographs, but we hadn’t seen a show in India yet with so many names.

And then the gallery wanted to fund it through sales, so they introduced a commercial criterion—which was not exactly something I was competent in, so nobody really knew how it would go. They did actually bring a version here [UK] and had a different kind of sale here.

I think it [selling] was really hard in India then. I don’t know if things have changed a lot, but my guess is that people weren’t used to buying photos or they were certainly not used to buying from multiples or editioned series.

RA: As exhibitions, when Where Three Dream, Cross was at The Whitechapel in London and then at the Fotomuseum at Winterthur, the displays appeared differently, even curatorially, at both venues. Could you say a little bit about this transition? (Images of the exhibition in last week’s post)

SG: Well, I have to say that no two exhibits of even the same material in different locations ever looked the same. So initially WTDC was very much devised only for Whitechapel Gallery, which is smaller. And even though we had about 550 pieces, it seemed more crowded.

And then in Winterthur, suddenly there was extra space and it kind of physically expanded. And I think, material was added in Winterthur, the book was revised with another cover, hardbound and of course with a German translation. The exhibition was bigger with more pictures, more colour (the walls were coloured) and the texts were highlighted and they had to translate them.

I think in Whitechapel, the curators and I worked very closely together throughout this whole research stage. But I think in Winterthur, Urs Stahel, who was the Director then; partly because of just the distance and partly because it wasn’t conceived for it; suddenly was able to have quite a big influence on how it was displayed. I think I made one trip to confer with him at a planning stage, but he pretty much was more able to say what it was doing and how it was going. Winterthur is located just outside Zürich and is very much in the European photography scene/mode—here[UK] it was seen by photo enthusiasts rather than the ‘art’ people and the large general public drawn to the Whitechapel generally.

I think it also reflects the way in which these things are setup, managerially. I had been employed by the Whitechapel over a long period of time so there was an ownership, but with Winterthur, I wasn’t employed by them. So after the Whitechapel show opened, I felt that my job was over.

Just now in Houston, it was complicated because I spent a lot of time there. I kind of just let it happen, but it’s not something that you can often do. I feel sometimes like an interloper because I’ve come from a photography background and then because of my involvement in curating I got involved with Fine Art, and now photography is in Fine Art in all of the teaching institutions and I’m back to teaching it as well.

They say it’s over, but there’s still a ‘photography versus art’ debate going on. If you see Photo London—it’s like a real photo world, it’s not like the Frieze Art Fair—everything is smaller and lower budget.

So it’s a bit like that in India—the way Kochi Biennale and the Delhi Art Fair are just impossibly large. I mean, photography’s not going to be at that scale, is it?

RA: If you were to think about an exhibition in which you had a completely free reign, to bring together whichever artists to expand the idea of India and photography from it—what would it be?

SG: That’s a big one!

I have to say that WTDC, not for lack of trying, couldn’t travel to India because a problem with India and big exhibitions is that they can only go to large spaces which tend to be government-run institutions and they’re really hard to work with, especially if you’re not used to them. And also the kind of lead times that people in the West have and the kind of a time they’d be on hold for, is limited. So it fell victim to that – the Whitechapel said they’re not going to pay for more storage time.

I will go on the record to say—I did go to a meeting in Delhi, a joint one involving the public sector and the private sector, at Lalit Kala Academy where the public sector said something like—”hands up, we surrender, we can’t do it. You guys do it.” So I was quite shocked and I’m surprised actually, that our Indian art world, which is so critical in its artwork, is not haranguing the government to give them a better public art sector, because otherwise we are the whimsy of the private art gallery or rich patrons—making us vulnerable to their moods.

I’m well trained in the system of a public sector—there is policy making in the ministry and that’s where you can affect change. That’s where you have the discussion and it’s all on record and civilized. There’s a kind of process that can be gone through as concerned citizen artists. If it’s private, then, how can you appeal to anyone?

As far this hypothetical exhibition is to be imagined, India is so full of ‘issues’. For example, I’m working with a research group in the UK at my university called Women in Photography. A lot of discussion happens within the group and of course it’s a lobbying group, but I’m waiting for them to discuss what a woman is, because that kind of gender discussion hasn’t taken place yet. Are trans-women to be included for instance? And that’s the kind of discourse taking place amongst my students. So there’s this discussion about gender; and then there’s this question of intersectionalities.

And in photography, outside of India, my problem is always that the perspective is colonial or and that one is looking at it within a certain history of photography, which is also colonial, and which doesn’t have any actors other than the usual suspects from here. So, I think there’s something to do with what’s now, somewhat incorrectly, being all being lumped together as ‘decolonising’, but some decolonising has to take place. Some unlearning of what they know has to take place.

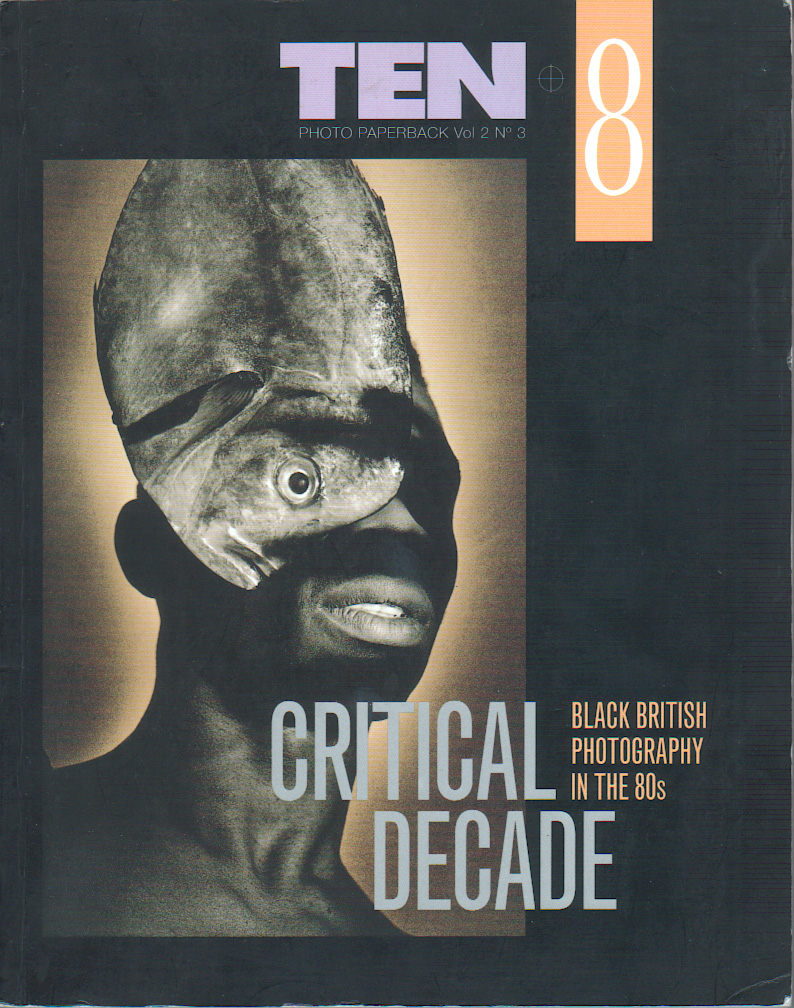

Critical Decade, issue of the Ten8 magazine, edited by David A. Blainey

Critical Decade, issue of the Ten8 magazine, edited by David A. Blainey

So I think a contemporary show should be within and about what’s transpired regionally. That’s why I think if we need have more courses in higher educational institutions researching it, other than just the one [NID], then we’d have more discourse. Otherwise, people are coming here [UK] to do their courses, and then it gets over-globalised and distracting.

And when you think India you think ‘gender violence’—that’s a important topic. And then ‘caste’. But that makes me feel nervous, because I wonder how you’d go about it. It’s such a minefield at the moment.

I think there’s a big critical tidal wave coming in India and I don’t know if people are ready for it yet. Questions like—how can privileged artists make work about the underprivileged, and make it their issue? In the Whitney Biennial for example, a white painter made a painting of the black man who was tortured in Chicago. People were saying—how can she interpret that experience? or Should she even be allowed to? Would that be censorship?

These are the kinds of discussions that are coming to India. Discussions about – who has a voice?

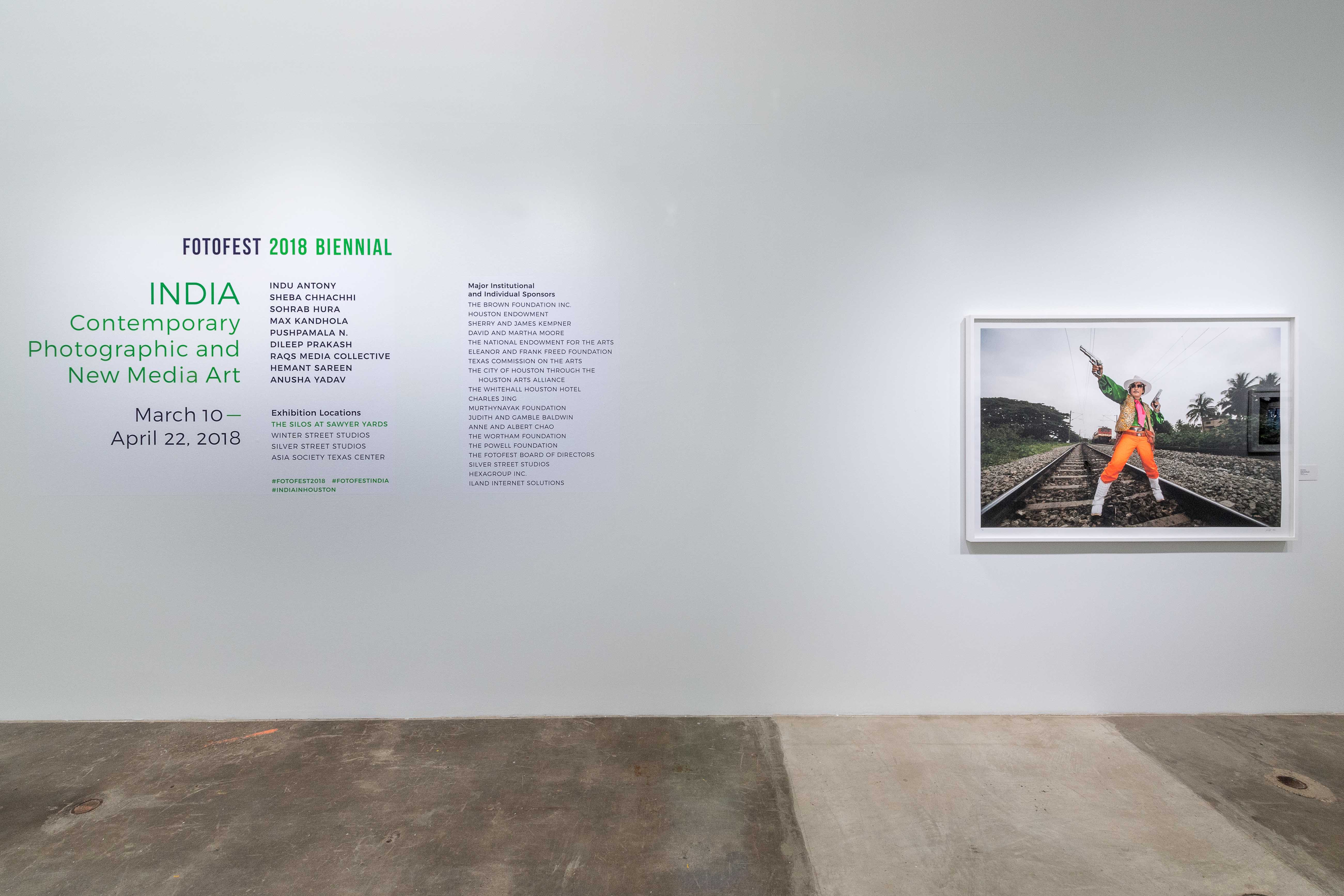

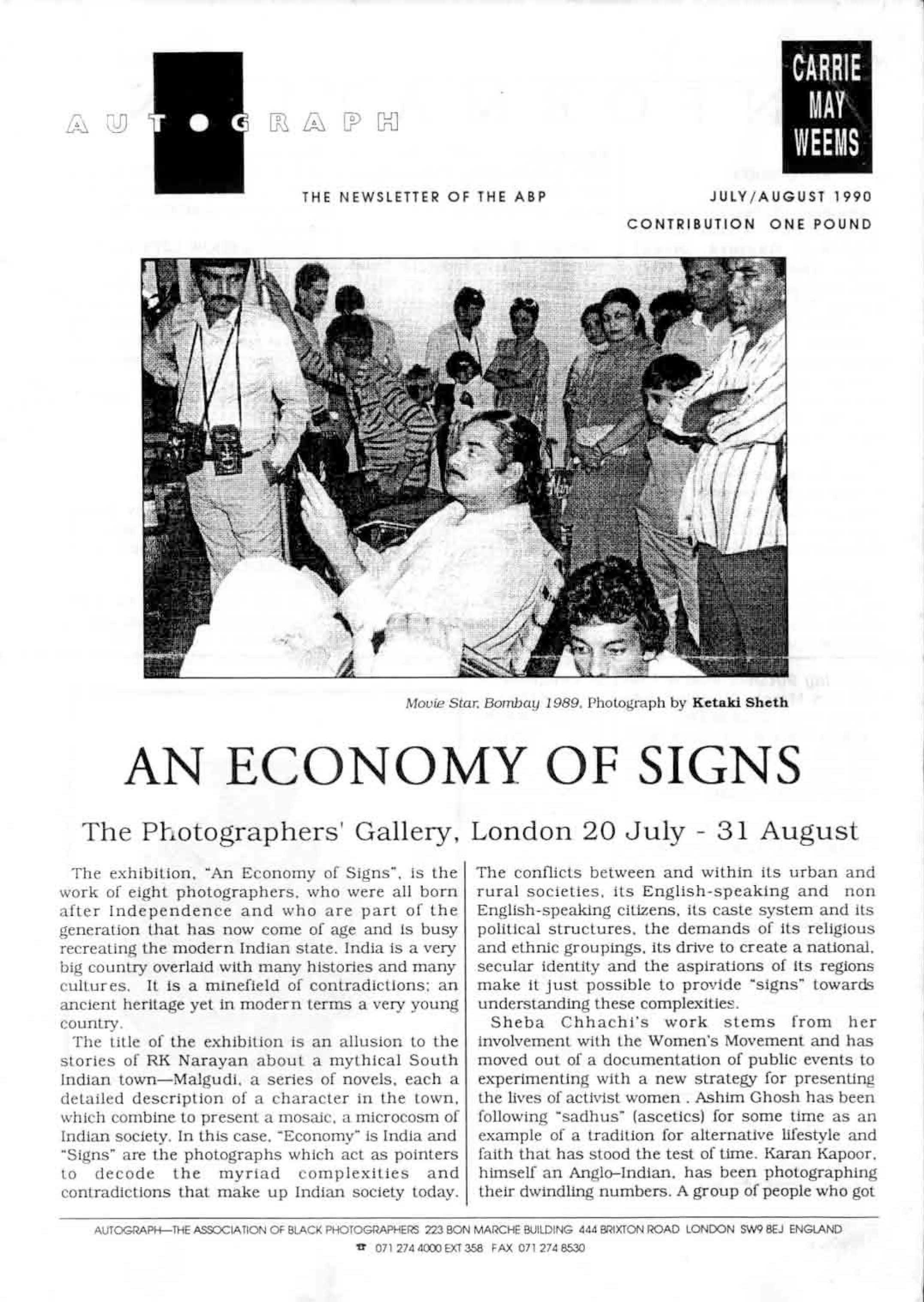

Spread from INDIA/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art

Spread from INDIA/Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art

Sunil Gupta is recognised as a photographer, curator, writer and activist for his works and engagements, which largely deal with issues such as racism, alternative sexuality and the voices from the leeway of society and culture. The subject matter in his photographs often poses a challenge to the viewer by bringing out conflicts that appear with the objectification of the viewed.

Also respected for his curatorial practice, Gupta’s exhibitions like, INDIA/ Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art and earlier exhibitions like Where Dreams Cross: 150 Years of Photography from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh at the Whitechapel Gallery, London in 2010, were very well received in the art world as well as in the media. His 2008 co-curated exhibition Click! Contemporary Photography in India is considered an important survey of the breadth of Indian photography at the time, and included over 100 photographs by 86 artists.

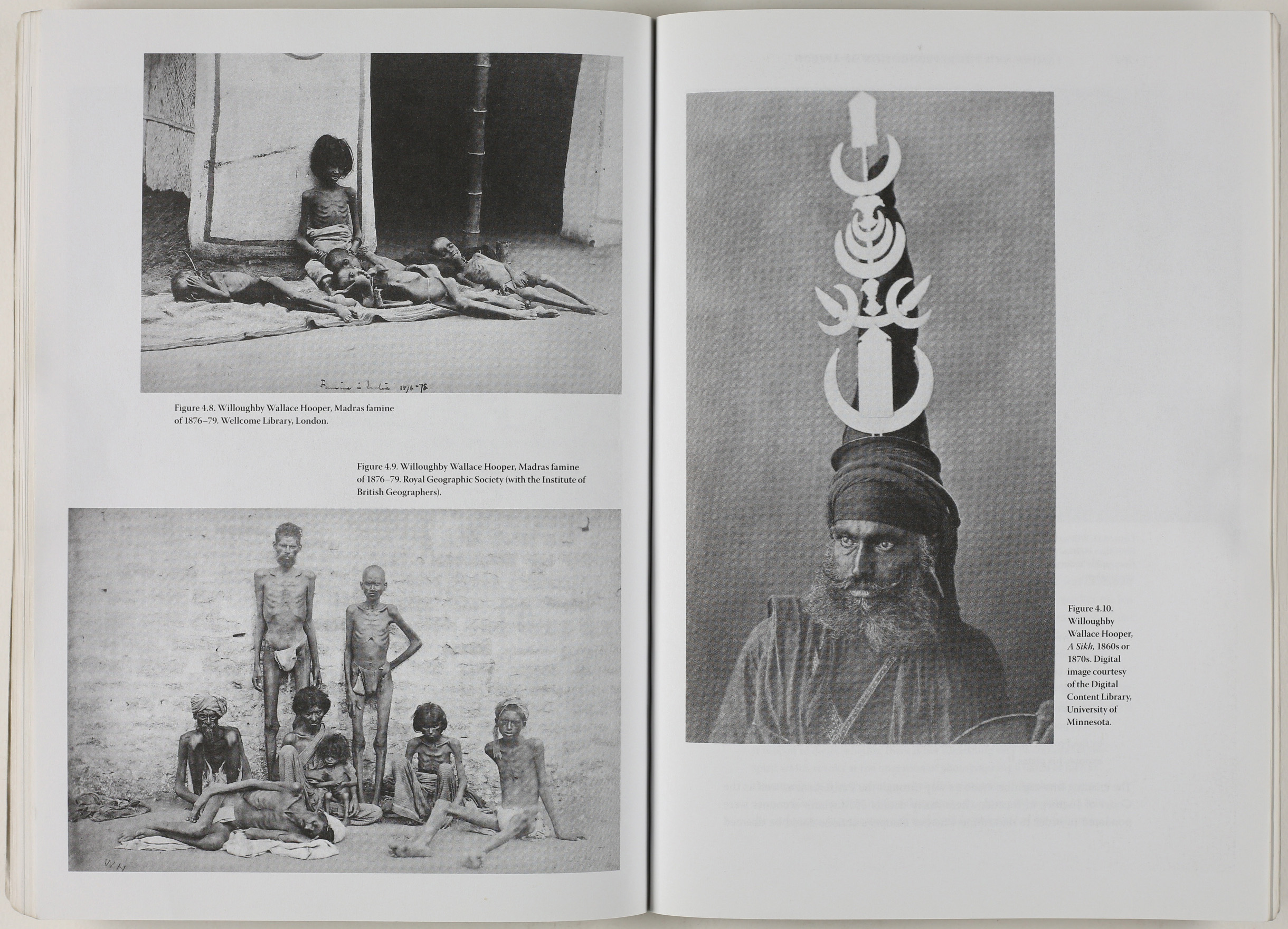

Spreads of Afterimage of Empire with famine images by W. Hooper

Spreads of Afterimage of Empire with famine images by W. Hooper

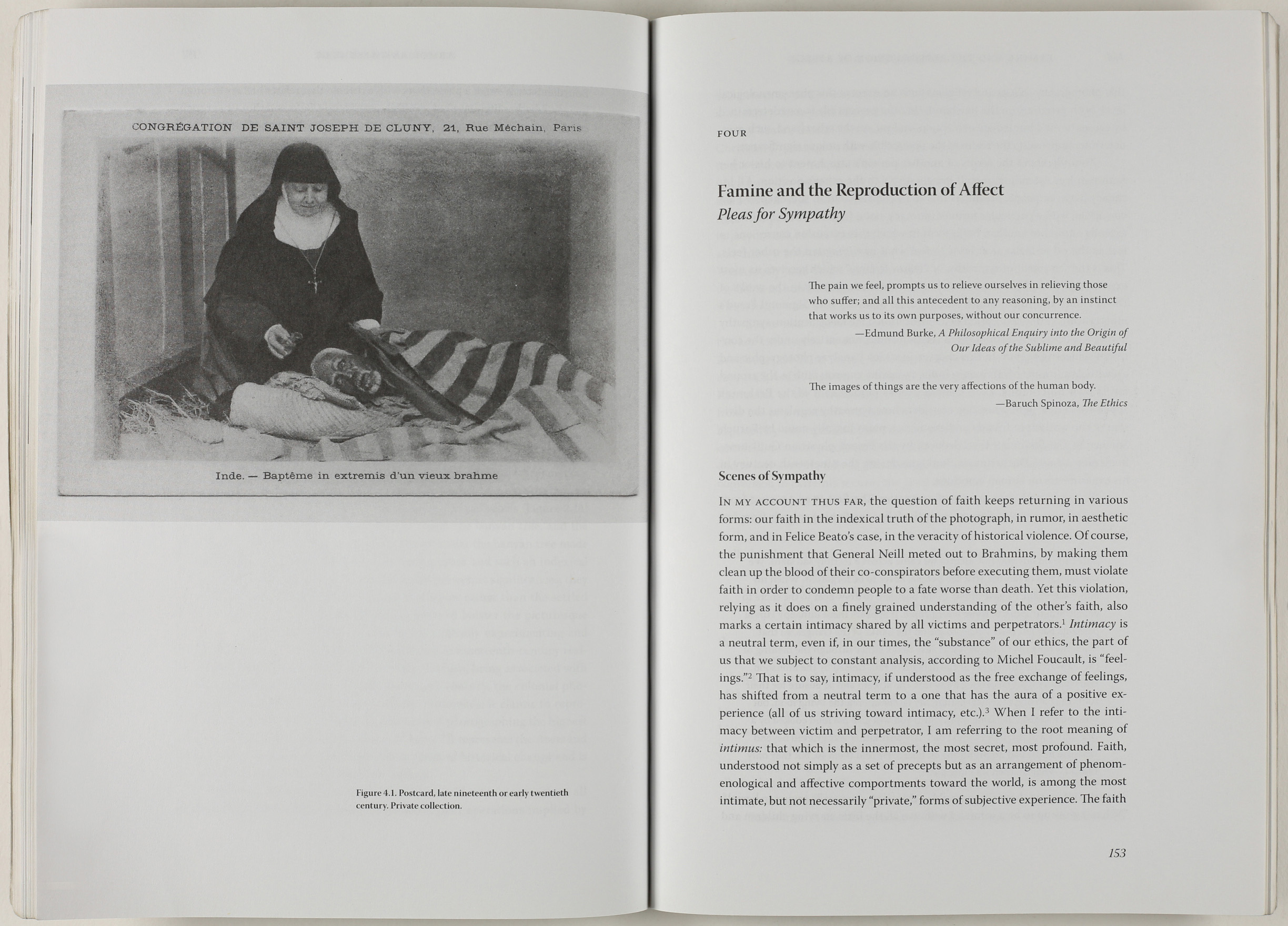

Spread of Afterimage of Empire with image by Deen Dayal

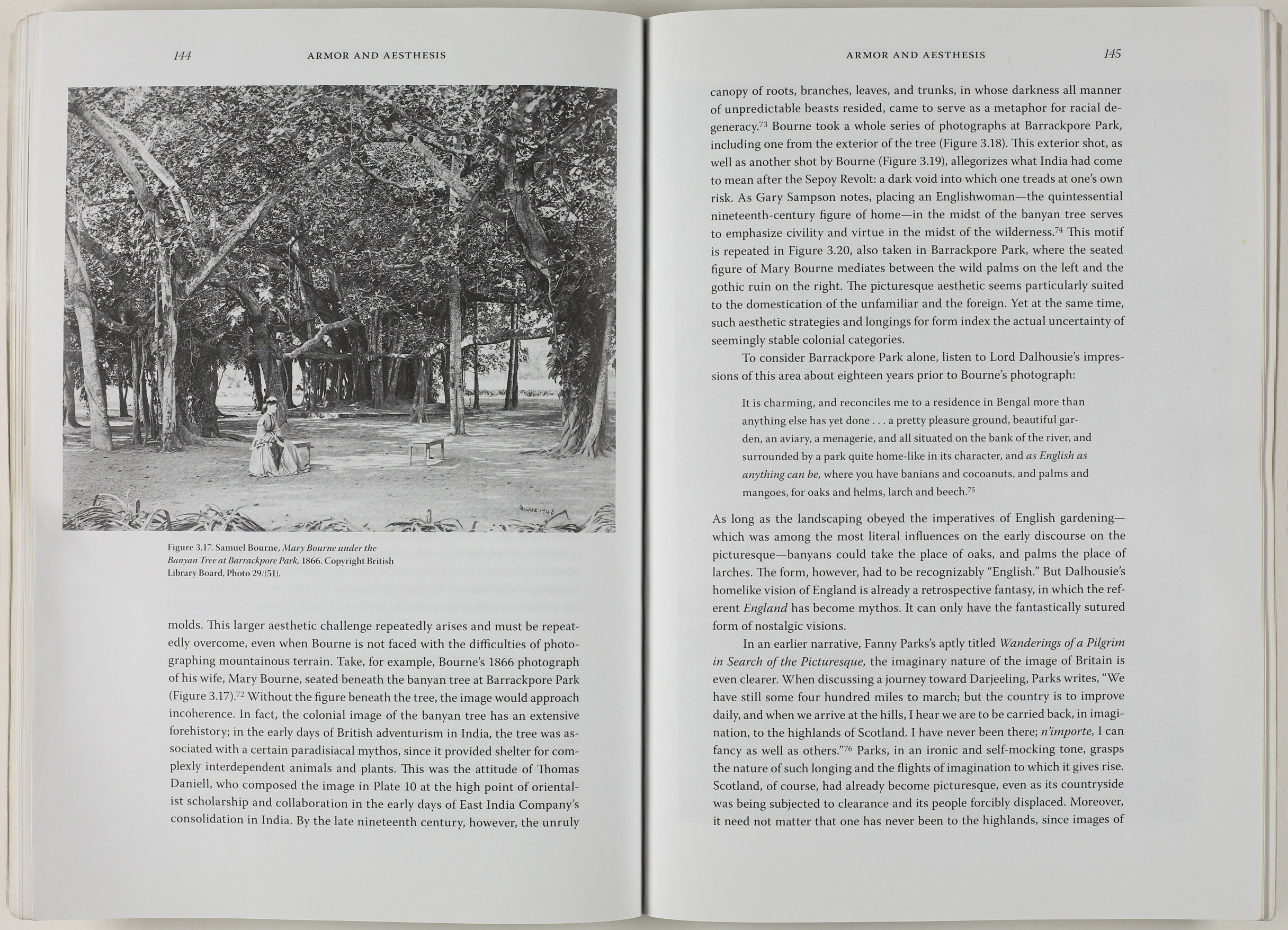

Spread of Afterimage of Empire with image by Deen Dayal Spread of Afterimage of Empire with image by Samuel Bourne

Spread of Afterimage of Empire with image by Samuel Bourne