Talking about FotoFest 2018 and other Curatorial Experiences with Sunil Gupta, Part 1

Cover image: Sandip Kuriakose

How do contemporary photographers and artists of Indian origin imagine the diverse and complicated subjectivities of Indian-ness, regardless of where they live? How do they communicate with a photography history that has remained Eurocentric for over a century and a half?

These are some of the questions and/or predicaments that underlie the premise of Sunil Gupta’s curation in the The FotoFest 2018 Biennal, held between 10 March – 22 April in Houston (Texas), featuring an exhibition of 47 artists of Indian origin working in the field of photography and new media practices.

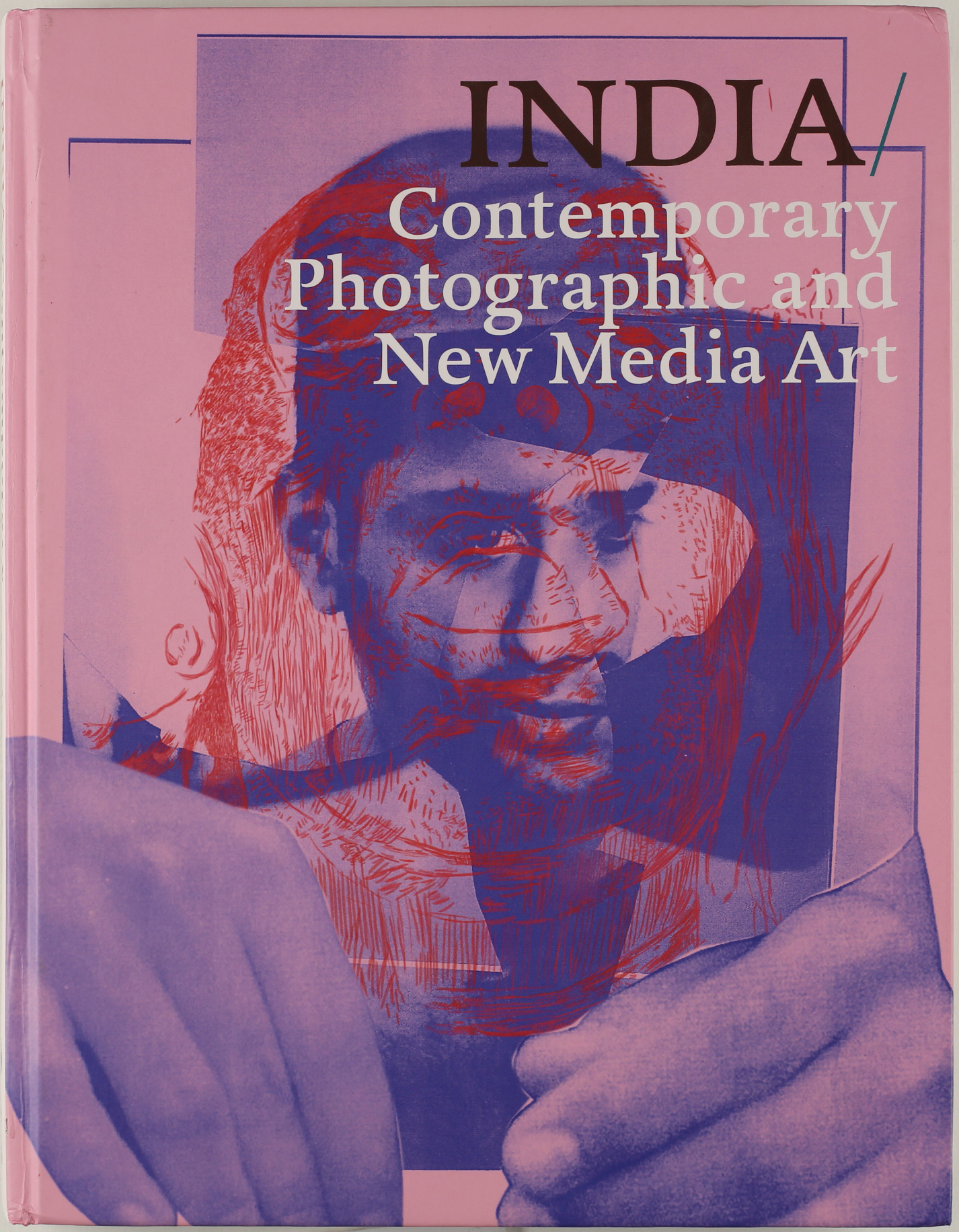

Sunil Gupta, lead curator of the exhibition titled INDIA/ Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art, has had a long and diverse career in the visual arts field, straddling heated debates about contemporary discourse, and an engaged activism around questions of identity and migration. His lens-based practice and years of study (and now teaching) go back to his formative pursuits in London since the 1980s, wherein he deployed all available means to investigate growing concerns in the field of photography as a form of social empowerment; notions of agency and representation.

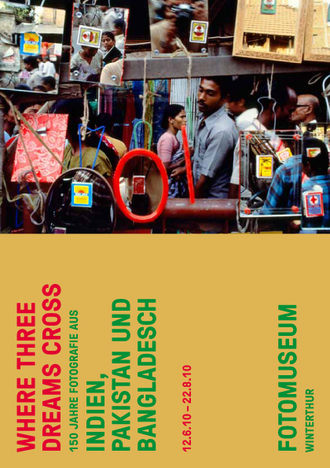

Working alongside practitioners in the field, often marignalised through the inner workings of the state via arts institutions and funding capacities, Gupta talks about the challenge of encountering art in politics and vice-versa. He also discusses previous exhibitions to which he was either exposed to or that he engineered/organised/curated such as Photography in India (1982); An Economy of Signs (1990) and Where Three Dreams Cross (2010), thereby articulating his sensibility about cultural power relationships within and outside pedagogy, canonisation and criticism. The work that he produces as well as curates makes us ponder: does the power of a photograph lie in its aesthetic invocation or in its social purpose—its capacity to direct our attention to material/conceptual dilemmas of the discursive systems in which it is embedded?

This week on PIX Posts, Rahaab Allana’s transcribed discussion with Sunil Gupta, probes his trajectory as an artist/curator; and his thinking through the notion of the ‘contemporary’ in photography from India—facets that have determined his curatorial vision for FotoFest 2018.

This is the first of a two-part post.

RA: What was the process by which you became the curator for the recent exhibition in Houston? When/how were you approached?

SG: I was first approached about the festival three years ago. It was when the [Houston] FotoFest had just put up the previous biennial about Climate Change, and they had done an earlier one with a focus on Arab culture with an external curator, so I wasn’t the first one to be brought in.

Fredrick Baldwin and Wendy Watriss of FotoFest, who by then had hired Steven Evans as Executive Director asked, “What if we make the Indian subcontinent the focal show in 2018?”. I think they were aware of Where Three Dreams Cross: 150 Years of Photography from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, so they were looking at a certain geography but were not looking at a historical perspective. As Founder Directors, they were actually pretty clear that it should be contemporary, not historical.

That triggered the same wheels in my mind from Where Three Dreams Cross (WTDC) left off. I suggested that we approach Hammad Nasar, Shahidul Alam, and potentially Radhika Singh, my great collaborator in Delhi. So that’s how it started – to take WTDC and make it about the contemporary with more or less the same co-curators.

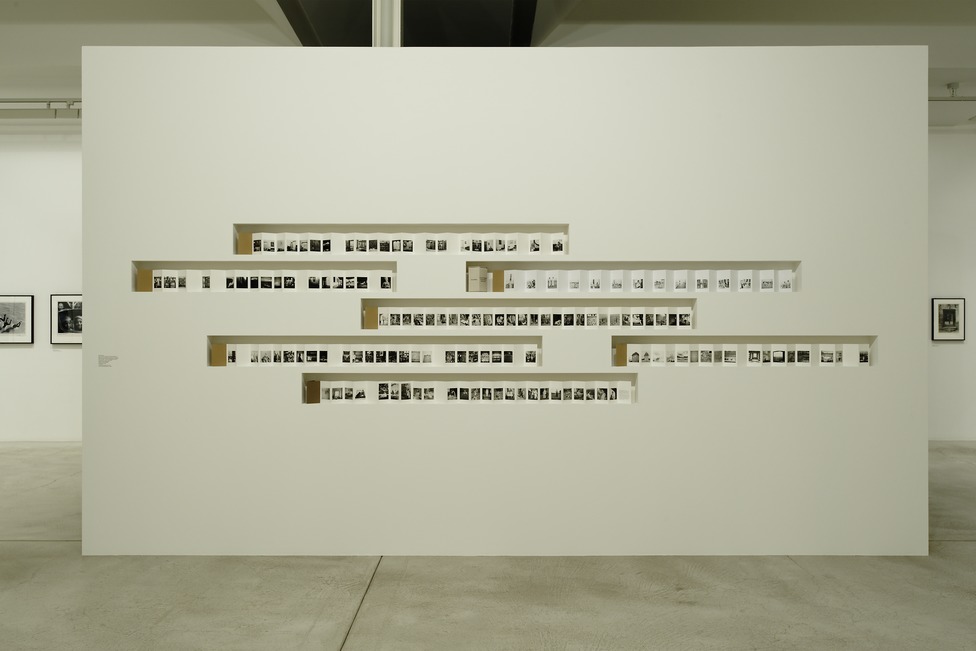

Exhibition views of Where Three Dreams Cross (2010) at Whitechapel Gallery, London

Exhibition views of Where Three Dreams Cross (2010) at Whitechapel Gallery, London

Exhibition informer of Where Three Dreams Cross (2010) at the Fotomuseum, Winterthur

Exhibition views of Where Three Dreams Cross (2010) at the Fotomuseum, Winterthur

Exhibition views of Where Three Dreams Cross (2010) at the Fotomuseum, Winterthur

RA: When you’re exploring and researching these particular curations – survey exhibitions, large encompassing shows which bring together histories of image production, how/where does your own practice come to bear?

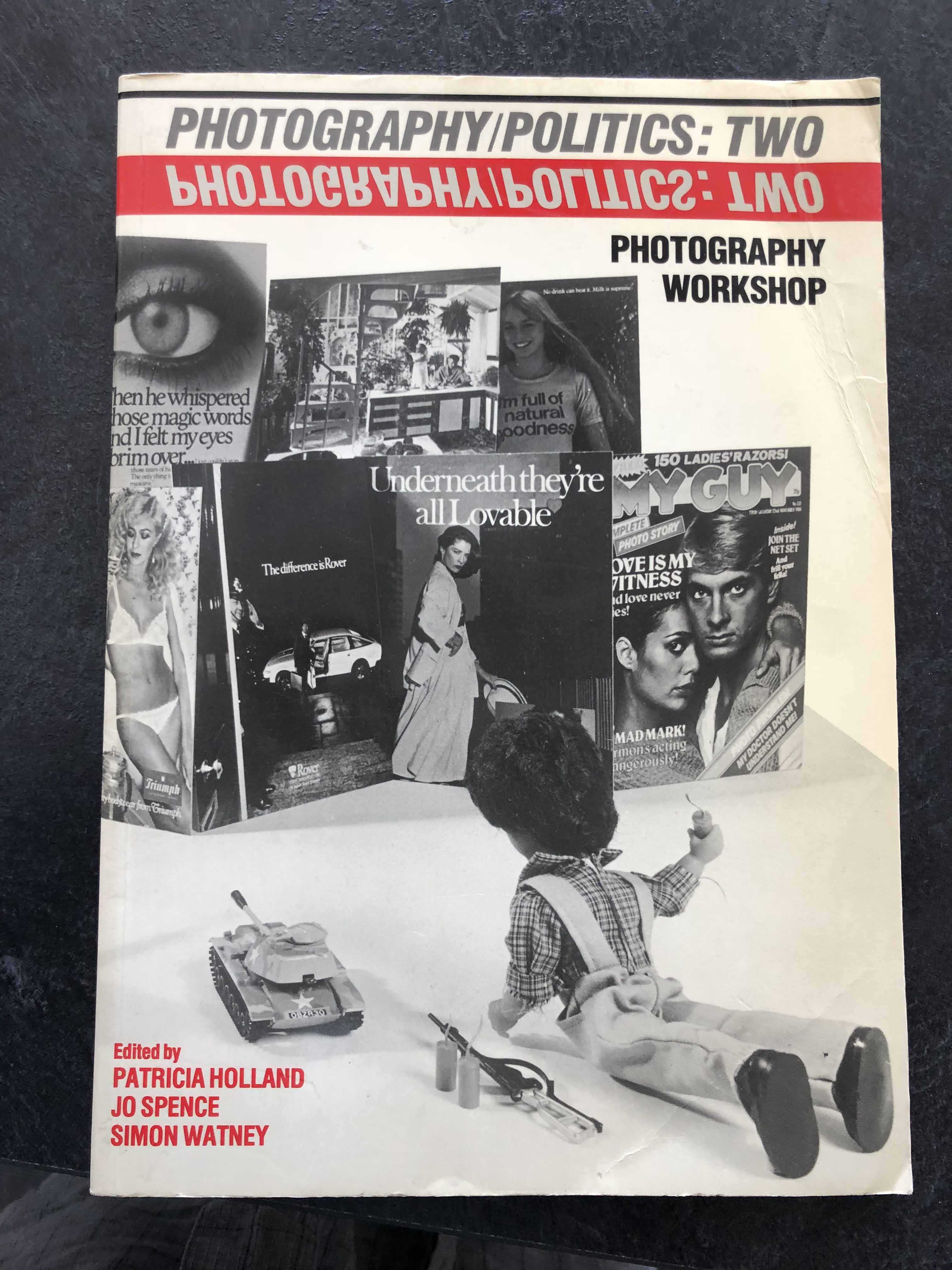

SG: I’m a product of what used to be called Black Arts in the eighties in Britain. So, my sense of practice is very wide—I primarily thought of myself and probably still do, primarily as not a fine artist nor a photographer but as a cultural activist which includes making work, curating shows, editing books, teaching and writing.

Catalogue of The Black Experience (1986)

Catalogue of The Black Experience (1986)

I came out of the Royal College of Art (RCA) in 1983 and went straight into the (Greater London Council’s) Town Hall and got involved with multicultural policy making and learnt how the arts fit into that. I learnt to appreciate how, in Europe or in the UK, arts and politics work together and how you serve marginalised communities and bring their stories in. And they are not only the audience and the subject, but also the citizen makers of those communities who need to come and tell their own stories.

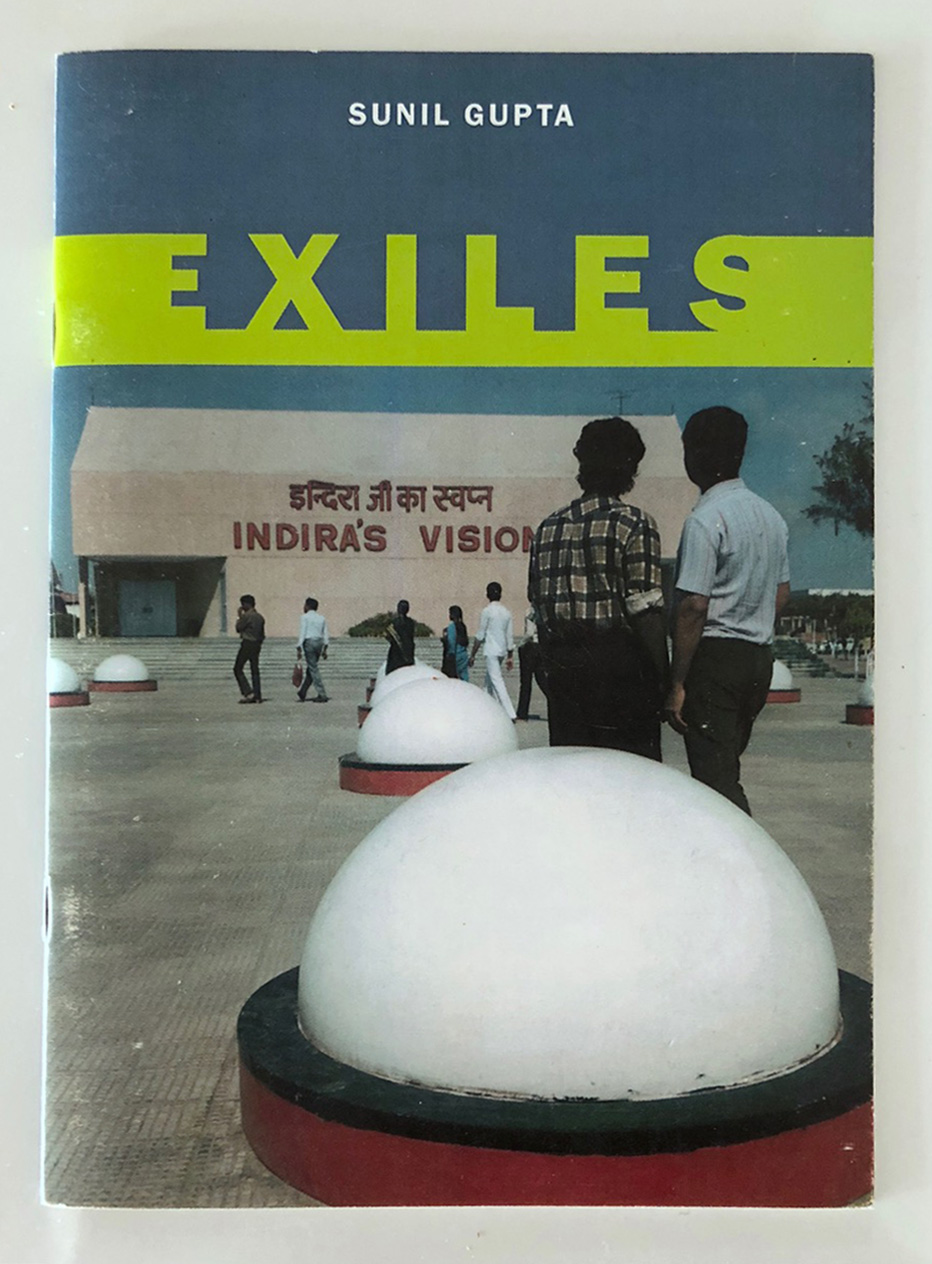

Sunil Gupta’s MA Dissertation (1983) from the Royal College of Art in print

Sunil Gupta’s MA Dissertation (1983) from the Royal College of Art in print

In a parallel way, I could also see that even after having come out of a very ‘elite’ institution, out of a very elite group of only six students a year, no curators were beating their drum to my door. So, if I was going to have a show, I was going to have to organise it myself…and if you were a person of colour, it was simply about survival.

In the eighties, museum curators in the UK were called ‘keepers’. They were actually the keepers of the collections. They were meant to be the people who knew everything there was to know in their collections. In France I believe to become a ‘keeper’, you had to pass an incredible IAS kind of exam where you were asked to indicate where pieces of art ‘lived’— in such and such place in the museum— as well as extremely in-depth knowledge about the work. But what they were doing was just organising objects and events in a managerial way, let’s say, not trying to reassess what should be in their collections in a post-colonial sense.

So, at that time, 1986, we had the first ‘black photography’ show with 10 people of colour (Blacks and South Asians), titled Reflections of the Black Experience organised by curator, Monika Baker and supported by the city hall. We became ‘organisers’ in that sense. As practitioners we became curators also because we were trying to foreground the absence of skills in our communities, because so many people from our background had not gone to art/history schools.

Then, as a collective—Autograph (an arts space and research centre), gave us a kind of bigger range of people to connect with and also share their skill sets. For example, when we started to do these group shows, making the prints became an issue. But I had been through a very ‘crafty’ photo school education at the University of the Creative Arts (UCA), Farnham and the RCA. Hence, I’m a printer, an analogue printer by training—so I made a number of prints for people. People would turn up with impossibly thin negatives; you’d have to make a print out of it.

We became ‘organisers’ in that sense. As practitioners, we became curators also because we were trying to foreground the absence of skills in our communities, because so many people from our background had not gone to art/history schools.

Exhibition catalogue for Autoportraits (1989)

Exhibition catalogue for Autoportraits (1989)

So that’s really what the organising was. But it was with a purpose, the purpose being to unseat Margaret Thatcher!

We learned a lot about policy-making and politics in that ‘real politic’ way. We went marching off across the (Thames) river to the Arts Council and said: ‘four percent of the UK is not white and we want four percent of your arts budget, and certainly your photo budget, whatever it is, however small it is…. and we want it because that’s who we represent. Who are you giving it to now? —none of those people know anything about this.’

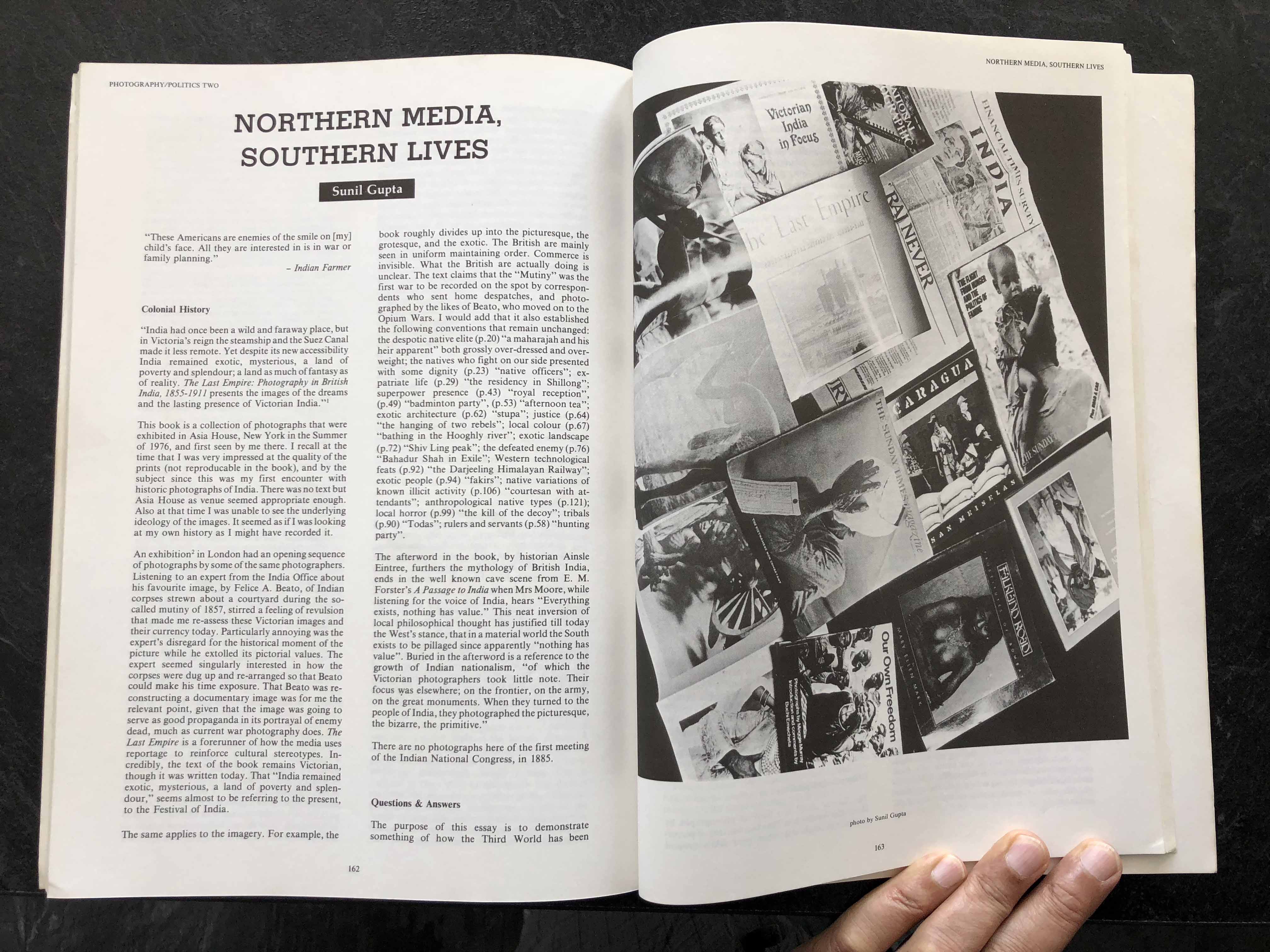

Catalogue and poster for The Body Politic (1987) at The Photographers’ Gallery, London

Catalogue and poster for The Body Politic (1987) at The Photographers’ Gallery, London

And they had to—they gave us £2,000 in 1988 to write a report: Are there any black photographers in the UK? which led to the formation of Autograph. It was true—in the late eighties you would talk to full-time curators in art institutions, museums and non-collecting places like the Whitechapel Gallery, and they had never heard of a ‘black’ photographer or an ‘Indian’ one for that matter… because there were none in books and none in historical surveys.

I too learned a [photography] history that was completely ‘white’… The British and the French brought it to us in India.

It’s never been taught. I too learned a [photography] history that was completely ‘white’… The British and the French brought it to us in India. So in the 19th century, I learned about Bourne & Shepherd, and Beato. I had no idea there were any Indians taking any pictures until I saw a private collection, the Alkazi Collection. And so, I met Sophie Gordon who maintained the collections in London.

RA: In your article as part of the publication that came out with the exhibition in Houston, you reference an exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery during the Festival of India in the 80s. Can you say a little bit about that exhibition, what you thought when you saw that?

SG: Oh yes, that was an exhibition in 1982 during the Festival of India.

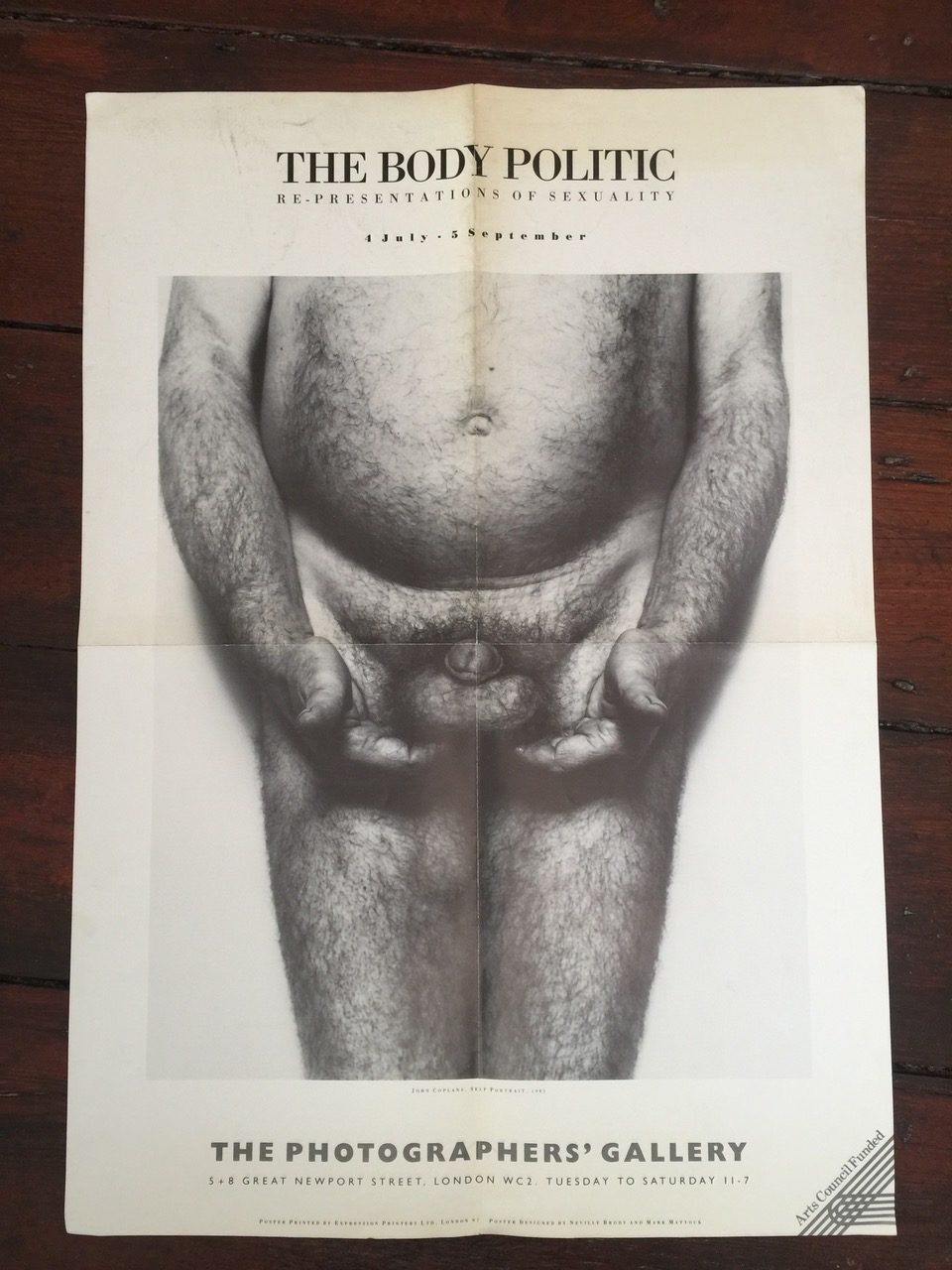

Exhibition catalogue and view of Photography in India (1982) at The Photographers’ Gallery, London

Exhibition catalogue and view of Photography in India (1982) at The Photographers’ Gallery, London

It was a little bit like ‘India shining’. So I’m not sure if that was entirely helpful for our purposes because it felt like something that was foreign and it came and went.

But people who had sympathies towards the subcontinent, went to see it and those who didn’t, didn’t. Also, India was not the emerging economic powerhouse on the global stage that it is now.

It was a little bit like ‘India shining’. So I’m not sure if that was entirely helpful for our purposes because it felt like something that was foreign and it came and went.

I don’t think it had much of a lasting impact on the photography scene here (UK) and it did not have a publication, which meant, as I later discovered as I began teaching, we had no teaching tools—so that exhibition virtually disappeared. But I met some of the artists like Pablo [Bartholomew], because I myself hadn’t been to India since I left in 1969. I began to go back actually just then in the early eighties, going straight to Rajasthan to shoot and not really having much to do with the Delhi scene.

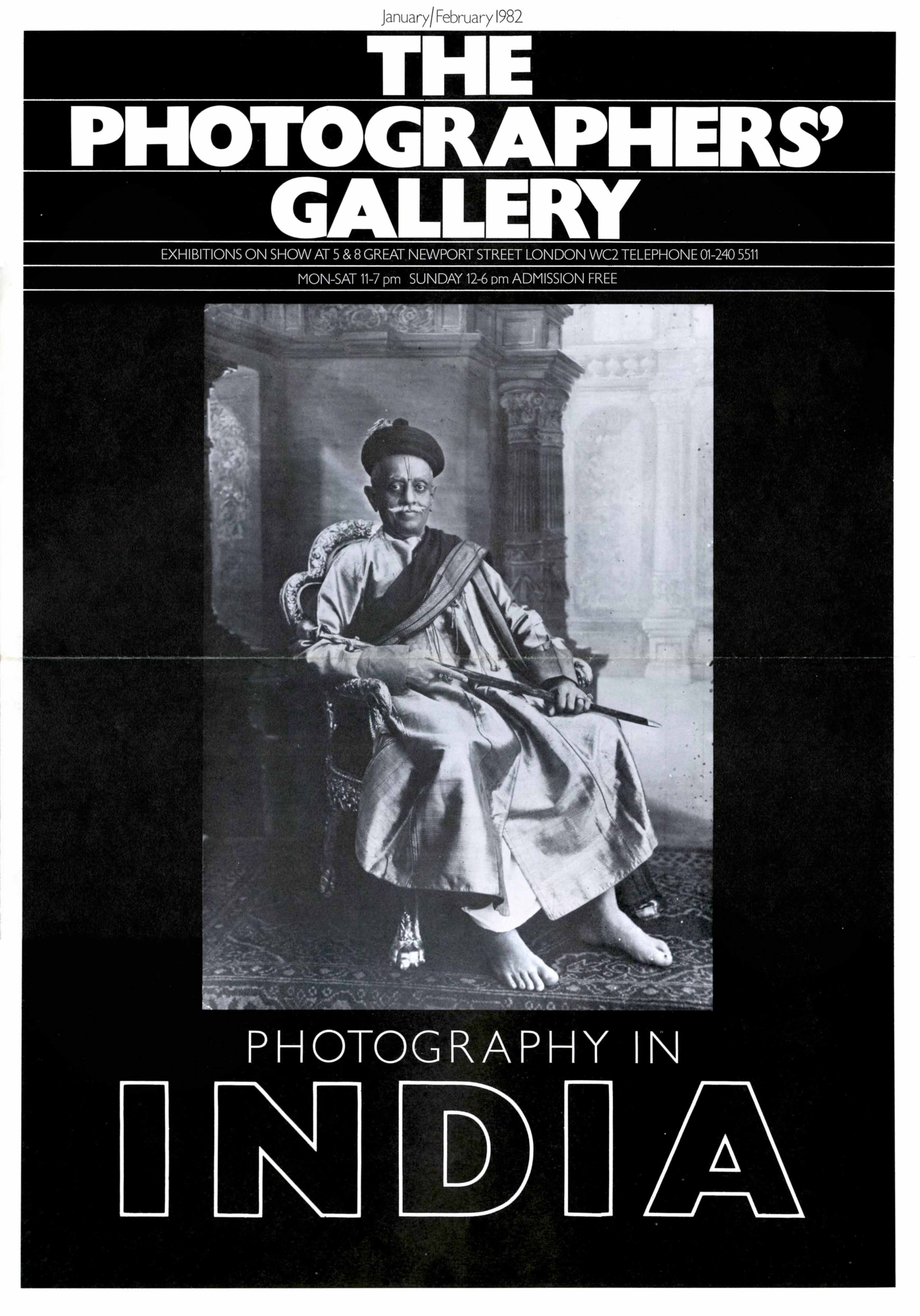

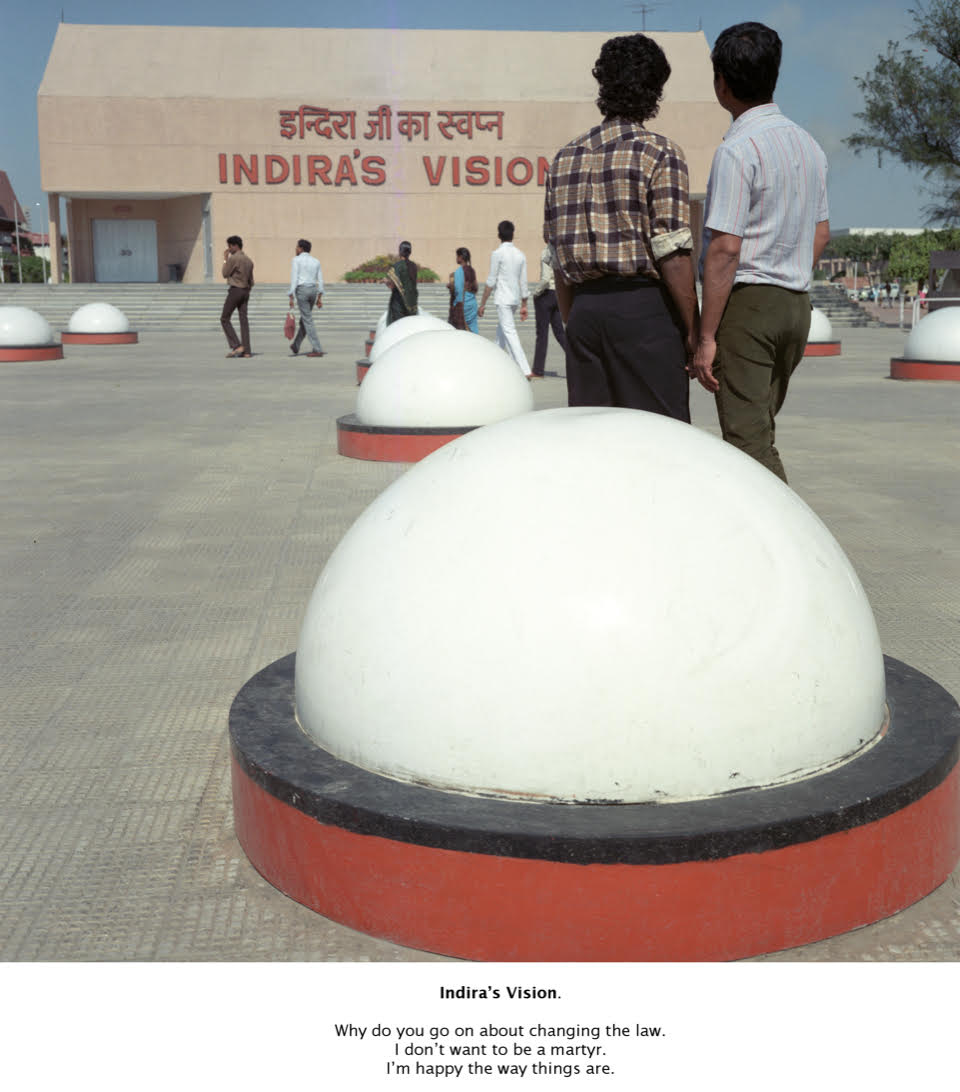

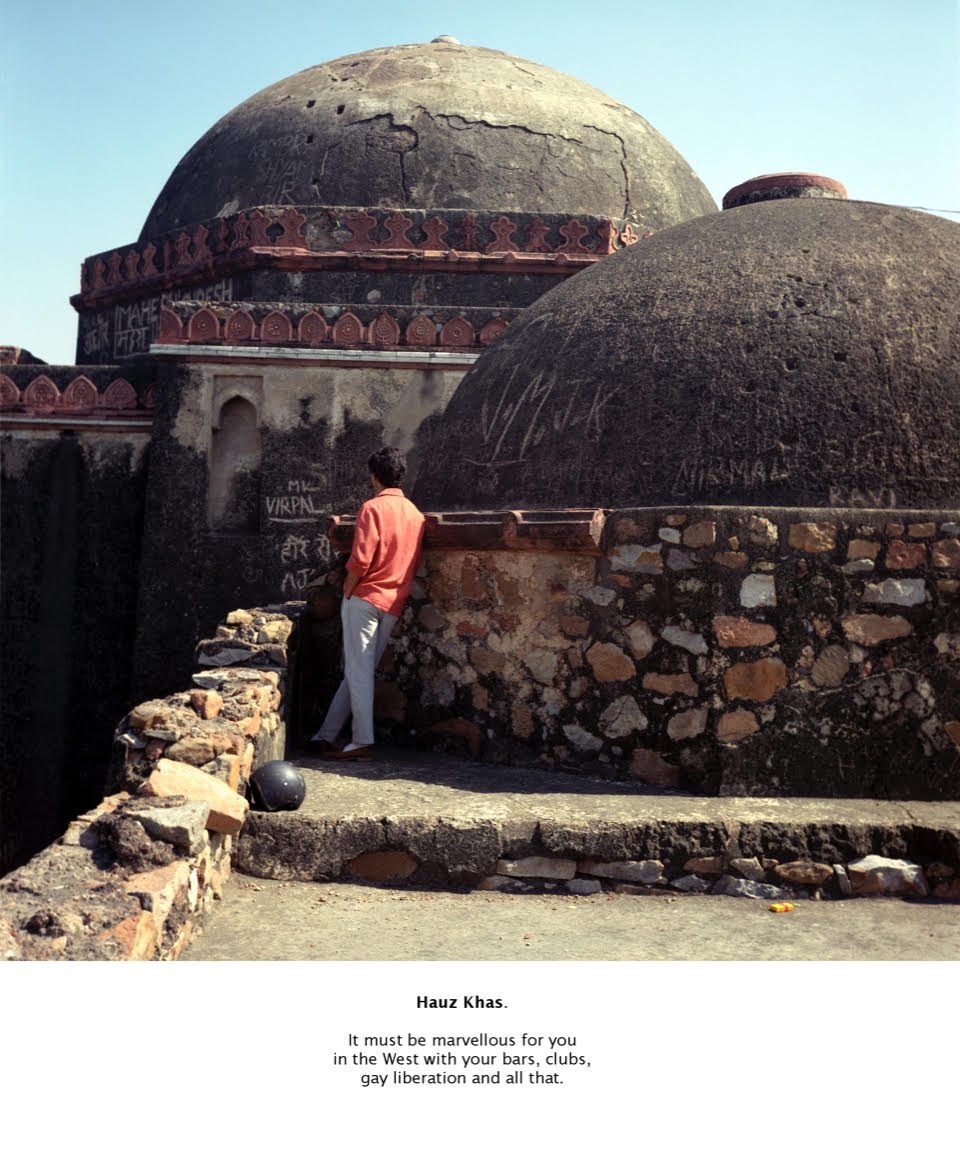

Catalogue and featured work from Exiles (1987; booklet 1999), a series about gay men in Delhi, commissioned by The Photographers’ Gallery.

Catalogue and featured work from Exiles (1987; booklet 1999), a series about gay men in Delhi, commissioned by The Photographers’ Gallery.

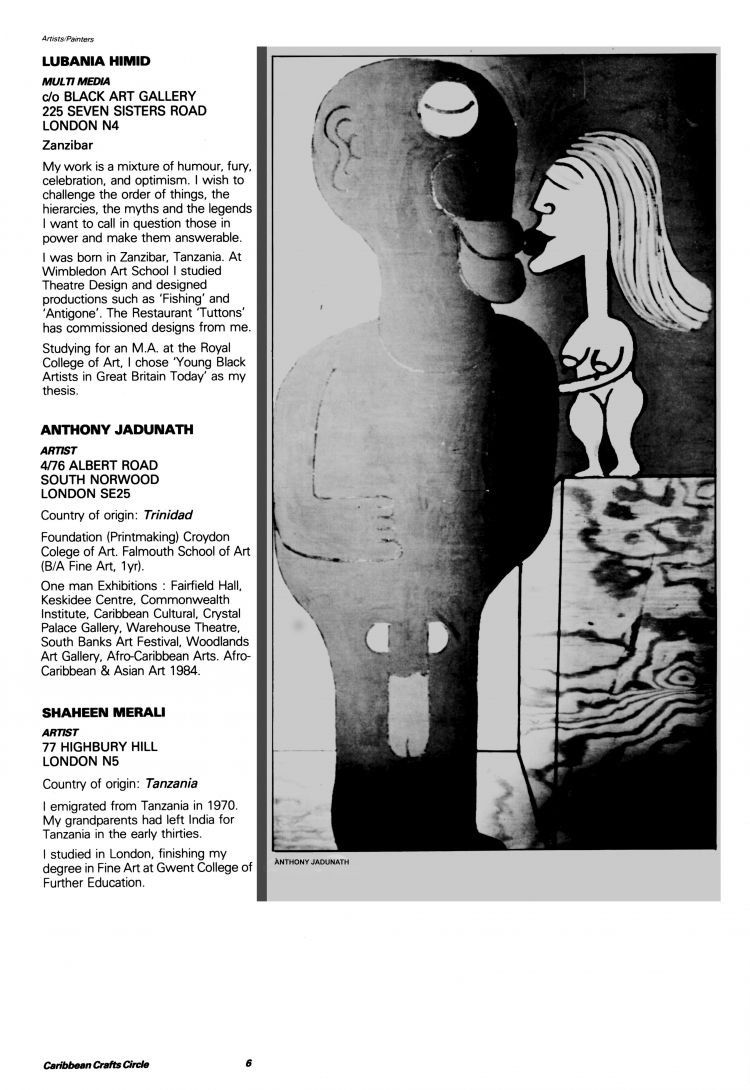

There had been various attempts here [in London] start things – an arts group called the Caribbean Craft Circle is an example. So they would take a weekend and put up stalls somewhere like the Covent Garden market and literally display whatever they made. I once had a stall with my photographs when I began to realise that that wasn’t an ideal way to sell something like photo prints. It took photography another decade since that time for it to be taken more seriously.

Artists’ directory of the Carribean Craft Circle

Artists’ directory of the Carribean Craft Circle

RA: In the Houston publication/exhibition specifically, there is an interest in the question of identity, how it is construed, also outside the country of its origins. So if one is looking at photography or any arts practice, maybe even literature as well, how does one actually think about the idea of location and identity ? What were the questions of identity that were being posed?

SG: The Houston exhibition was narrowed down from the entire subcontinent to just India for budgetary reasons, so we immediately lost all the neighbours…also partly for time reasons.

Then I began a discussion that it can’t be about the ‘place’ India because then we’d have a very different kind of exhibition. A lot of people go and shoot pictures in India, those who live there and those who don’t live there; Indian or not Indian. And if, ‘ethnicity’ (in a very specific sense) has been left out of history, we need to keep bringing it back in, so let’s take out all the non-Indian origin people and then just be left with people with origins from India whether or not they lived there.

I also wanted to work with people I’ve already worked with and they tended to be the older, more established practitioners. And I wanted them to somehow be brought together with younger photographers, even students about to emerge from college. I wanted to reference the diversity of the Indian diaspora with their trajectories having taken them to opposite ends of the globe—Fiji in one case and Trinidad in another. I also pondered whether there is a global Indian identity? I mean, there are enormous differences between say me here in England where I work and live now compared with a lot of second, or third generation Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani origin people. Although people say identity politics has been on the wane in the 2000s, it seems to be making a comeback in the current politics of Trump and Brexit.

In addition, looking back on the exhibition now, it seems to me that the exhibition was a very big success in the sense that it fulfilled many of the requirements of photography—the diversity of approaches and techniques; the diversity of gender. There was almost an equal balance in terms of practitioners, and I think there was a big diversity of age range too.

And there was a huge range of, what in the West, people accepted as the kind of critical practice—an almost academic practice without the ‘academy’. So that was interesting because, you know, we’re short of that in India.

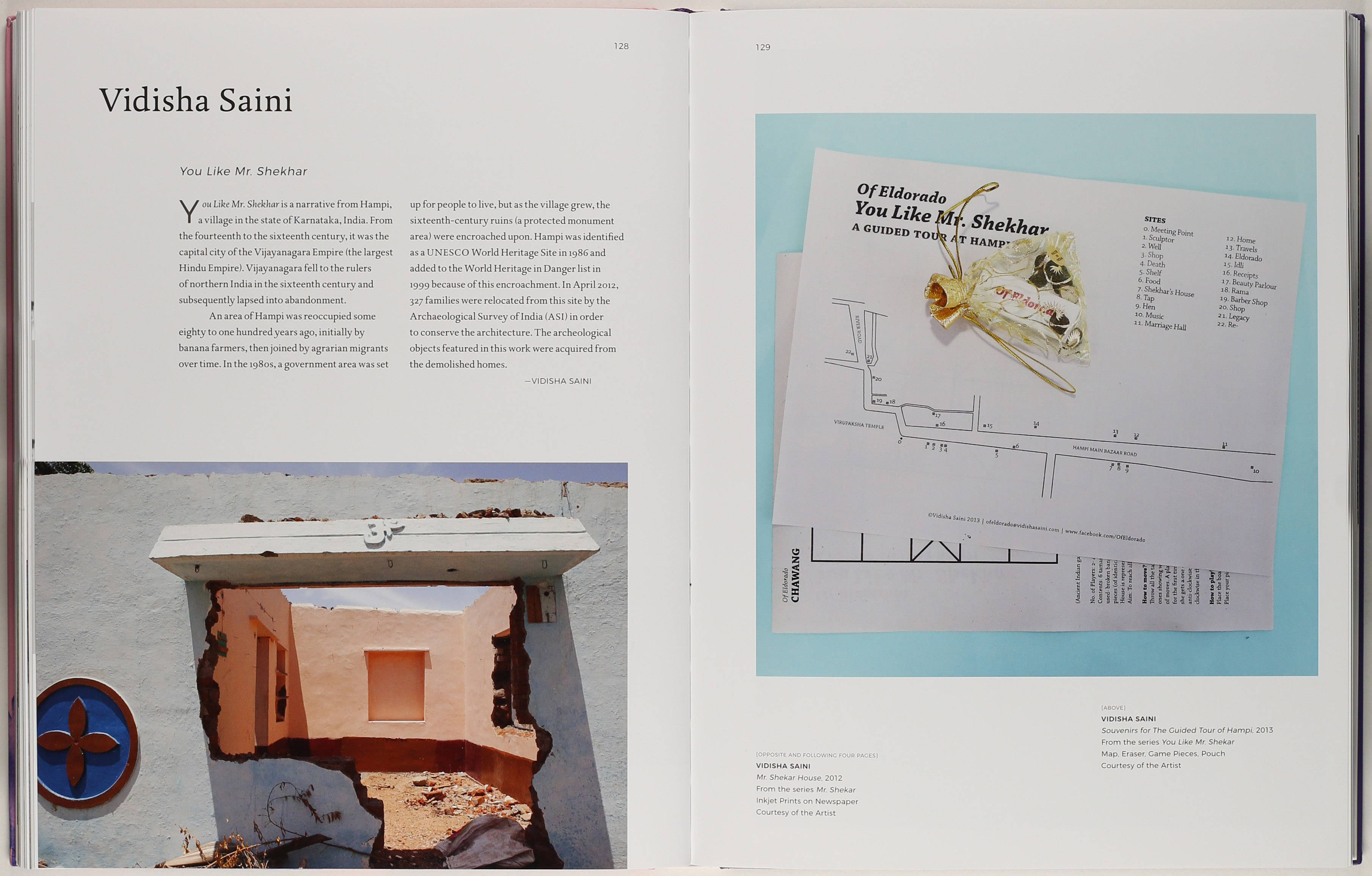

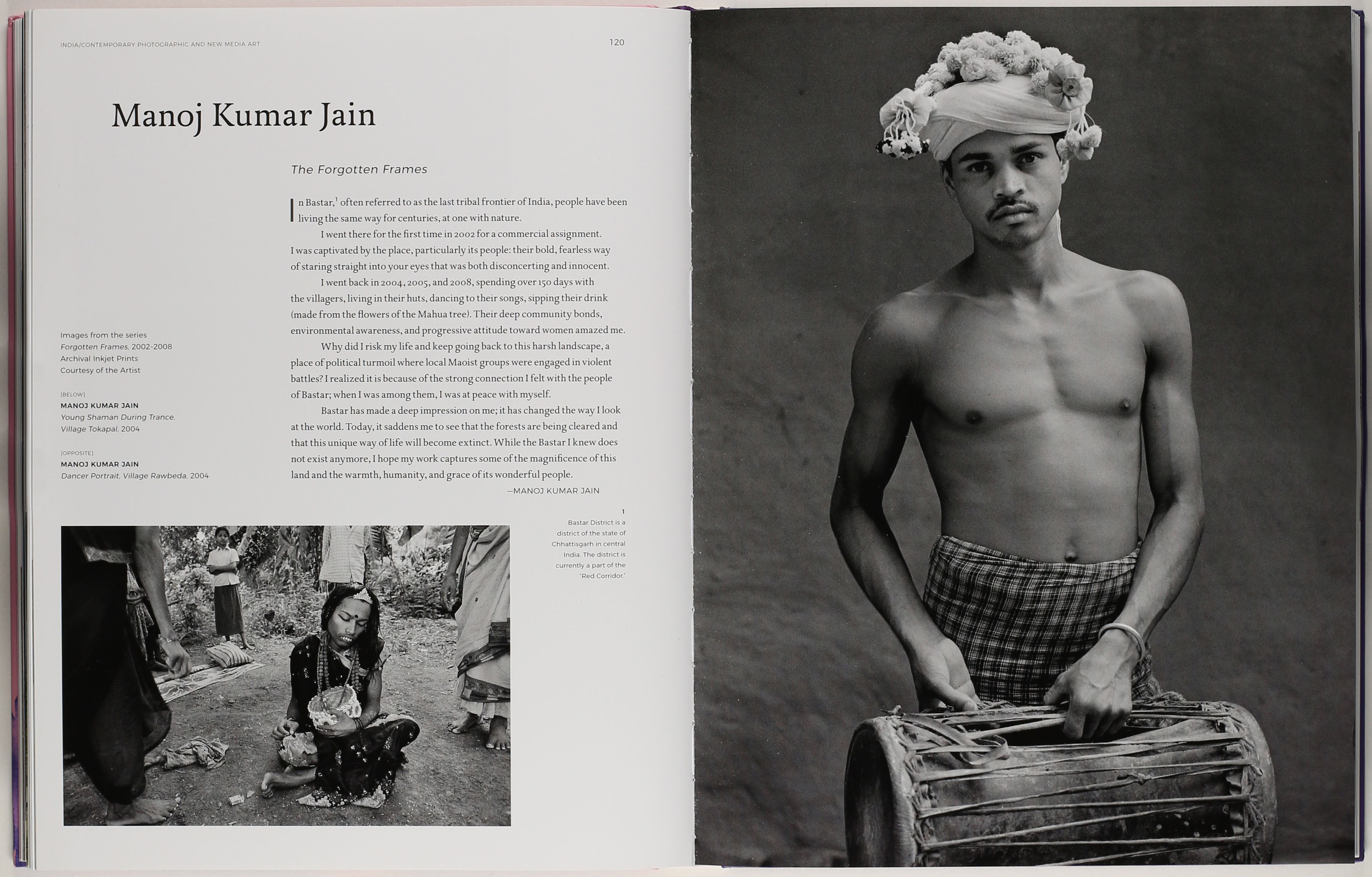

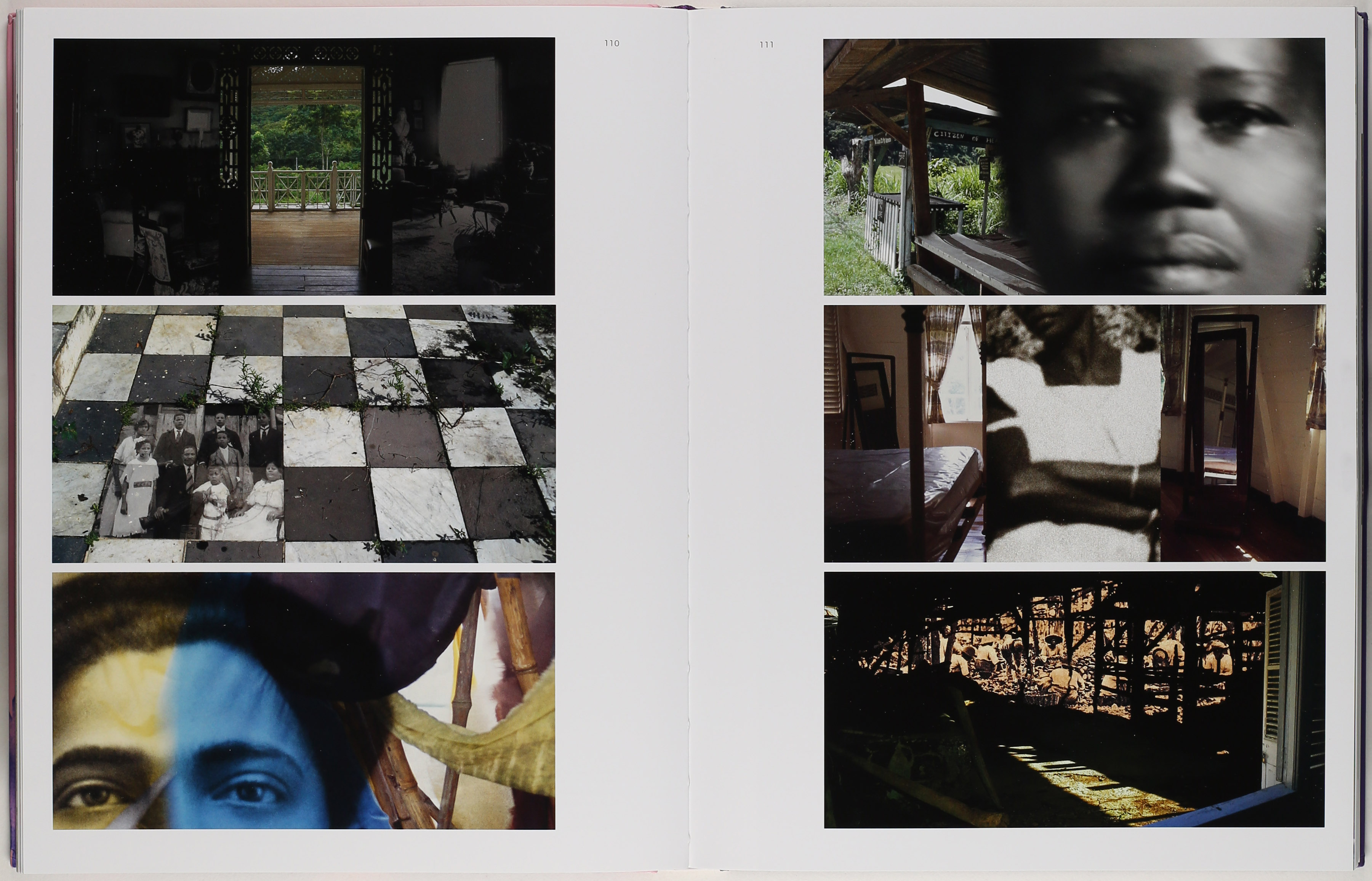

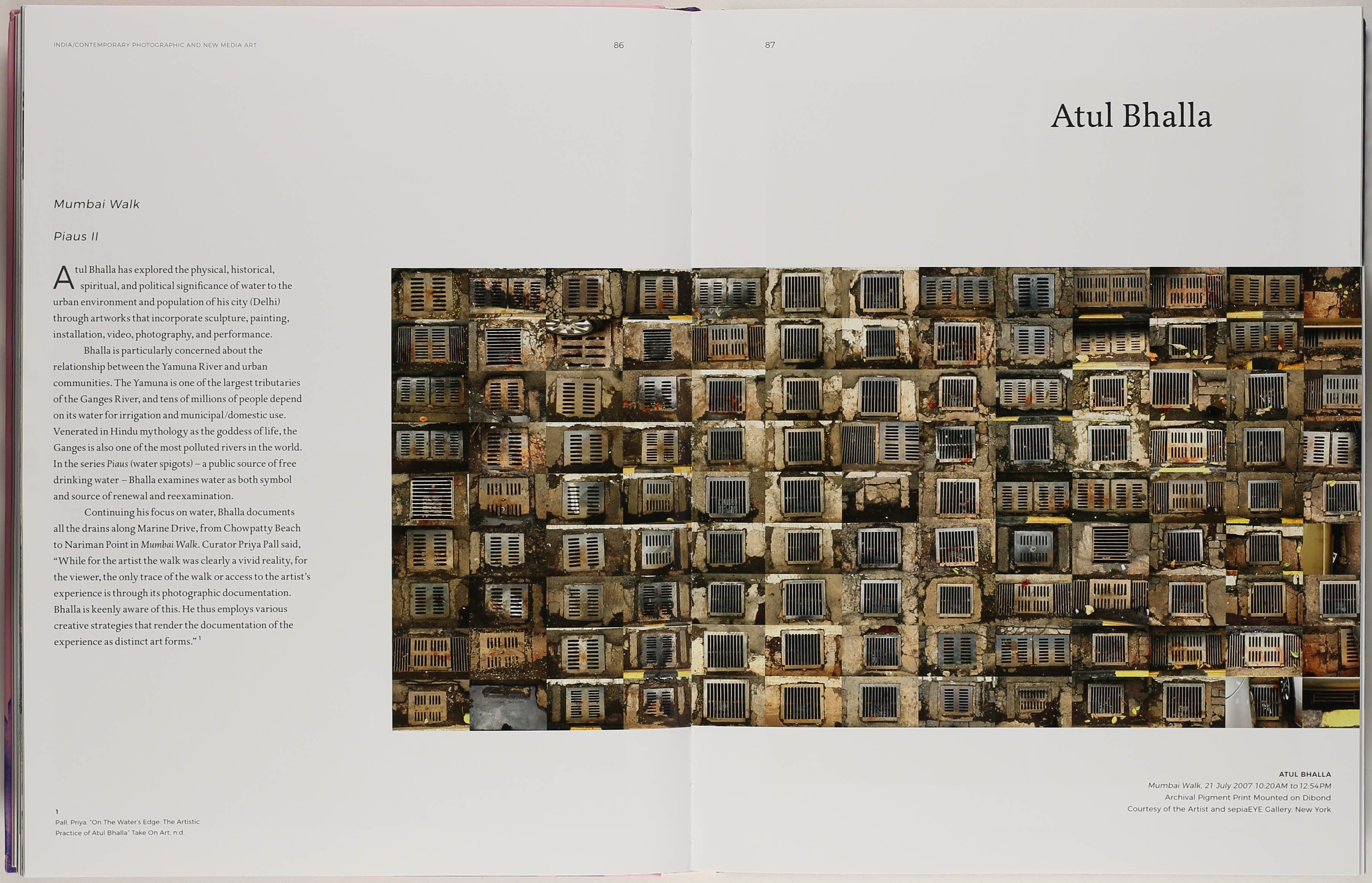

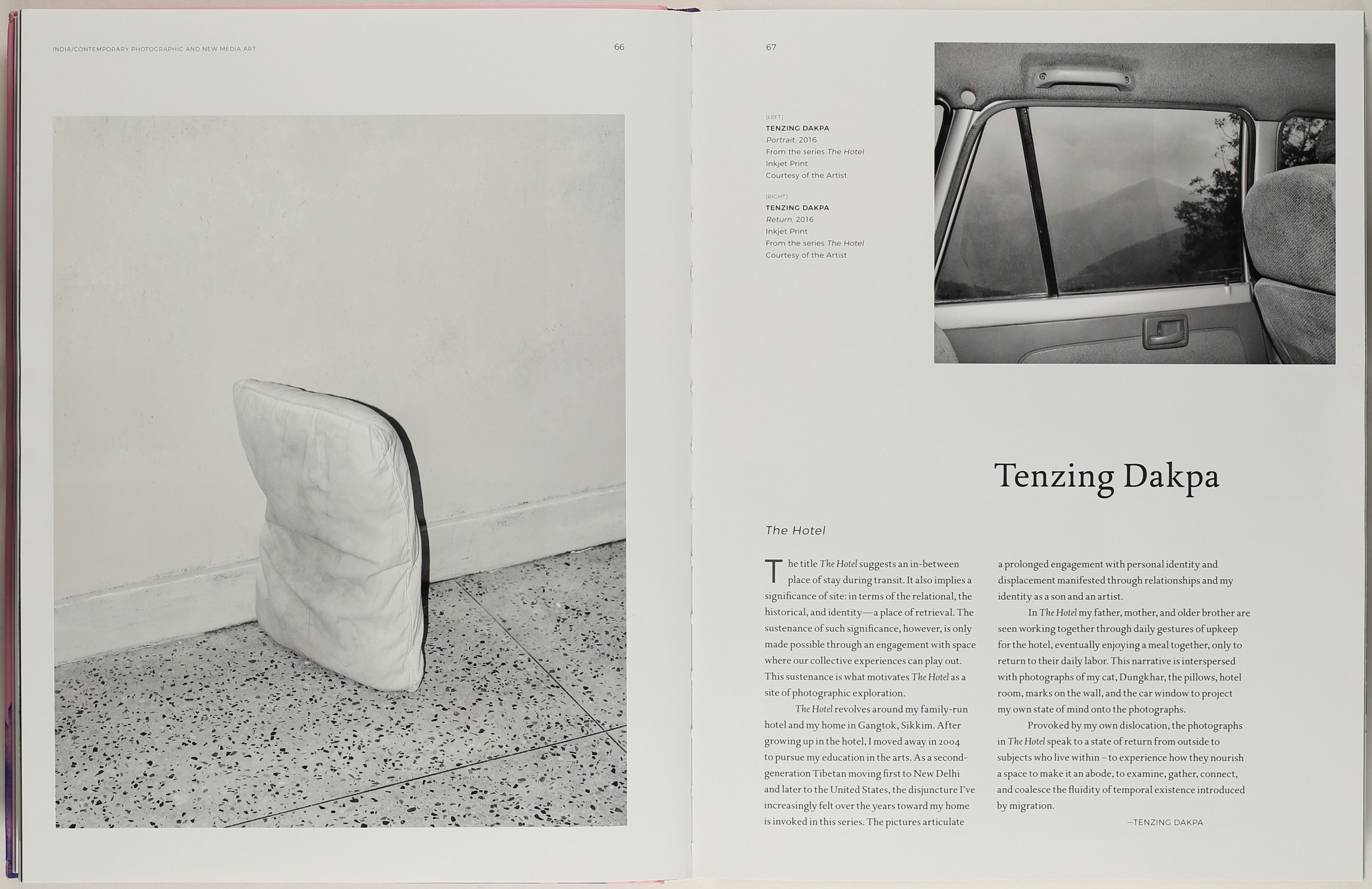

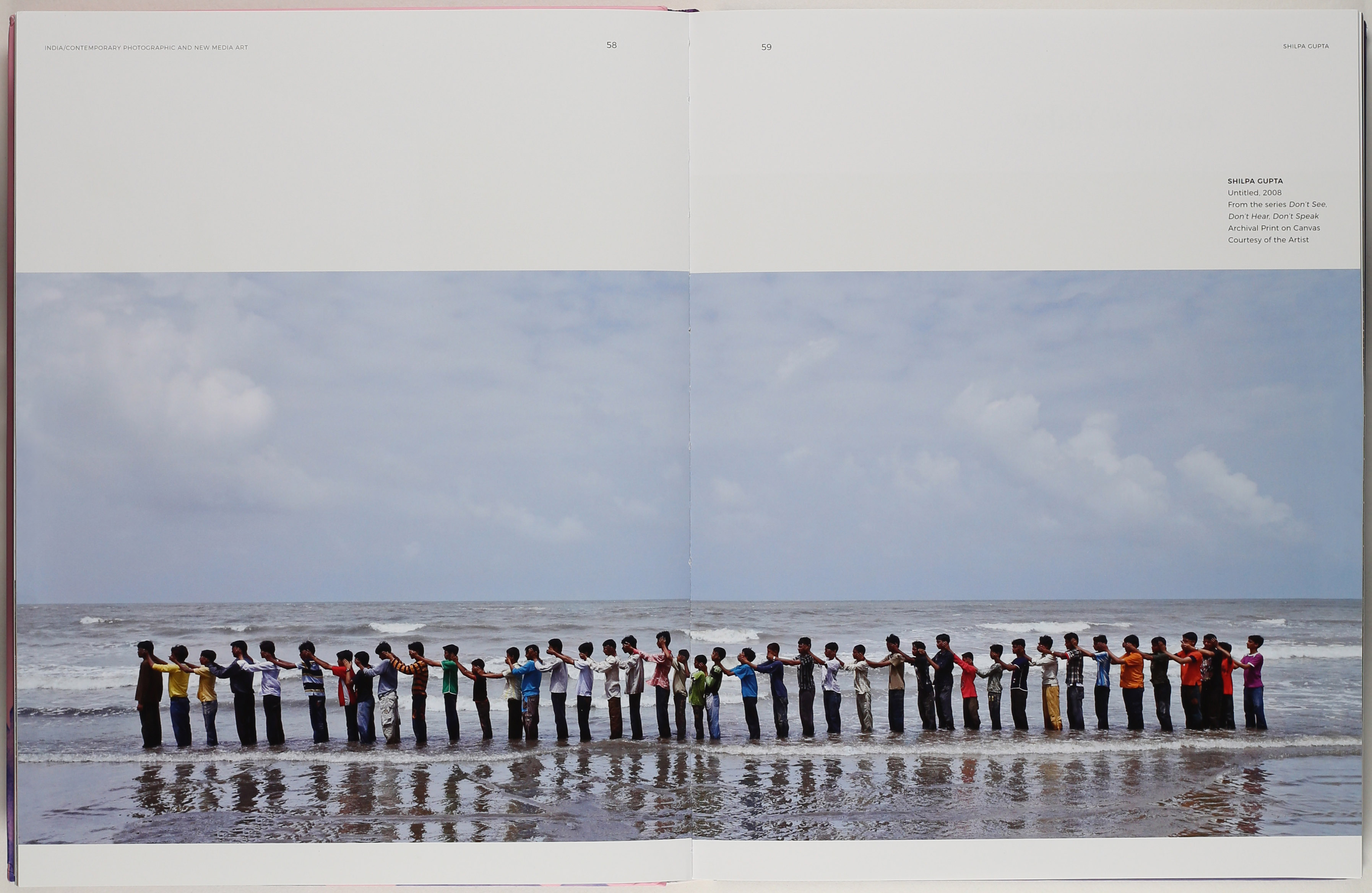

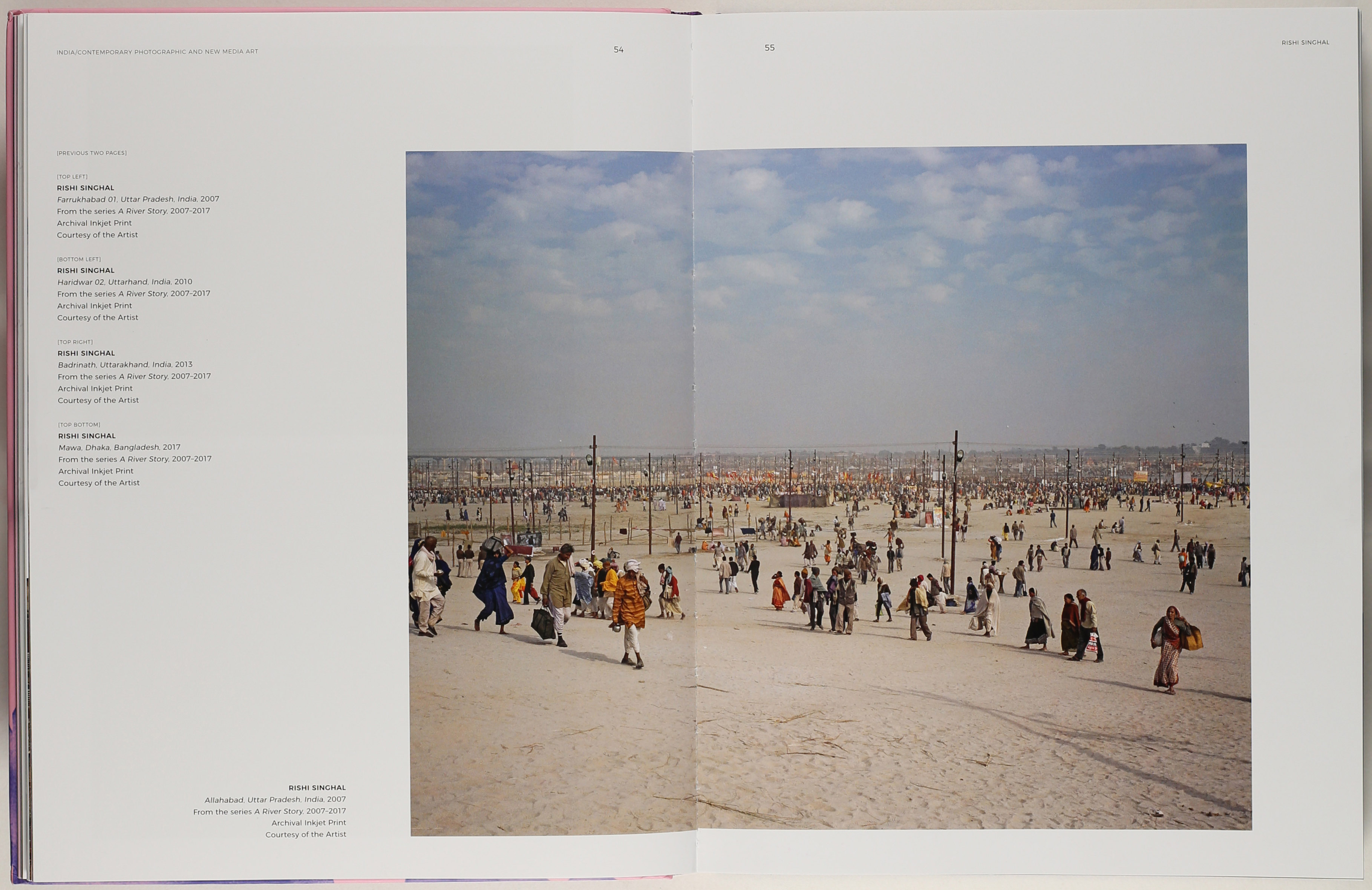

Spreads from INDIA/ Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art (2018)

Spreads from INDIA/ Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art (2018)

Sunil Gupta is recognised as a photographer, curator, writer and activist for his works and engagements, which largely deal with issues such as racism, alternative sexuality and the voices from the leeway of society and culture. The subject matter in his photographs often poses a challenge to the viewer by bringing out conflicts that appear with the objectification of the viewed.

Also respected for his curatorial practice, Gupta’s exhibitions like, INDIA/ Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art and earlier exhibitions like Where Dreams Cross: 150 Years of Photography from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh at the Whitechapel Gallery, London in 2010, were very well received in the art world as well as in the media. His 2008 co-curated exhibition Click! Contemporary Photography in India is considered an important survey of the breadth of Indian photography at the time, and included over 100 photographs by 86 artists.

Comments