Recounting the photography exhibition: Behind the Indian Boom

Photography as a form of critical social engagement comes to the fore in exhibitions like Behind the Indian Boom: Inequality and Resistance at the Heart of Economic Growth, curated by documentary maker, Simon Chambers and Dr. Alpa Shah (Associate Professor-Reader in Anthropology, LSE) at the Brunei Gallery in SOAS, which was on view between 13 October and 16 December 2017; and subsequently installed at the LSE Arts Atrium Gallery between 15 January and 15 February 2018. The exhibition draws on research undertaken across India as part of an ESRC- and ERC-funded Programme of Research on Inequality and Poverty based in the Department of Anthropology at LSE led by Dr. Alpa Shah and Dr. Jens Lerche (Reader in Agrarian and Labour Studies, SOAS).

Viewer comments of the exhibition*

Viewer comments of the exhibition*

The display was based on in-depth anthropological/social research and arguments presented in the recently published book by Pluto (2017; in India by OUP, 2018) titled Ground Down by Growth: Tribe, Caste, Class and Inequality in 21st Century India, co-authored by Alpa Shah, Jens Lerche, Richard Axelby, Dalel Benbabaali, Brendan Donegan, Jayaseelan Raj and Vikramaditya Thakur. The exhibition presented images taken by the authors, other academics and PhD students affiliated with the LSE research programme, as well as known photojournalists. It re-focuses our attention on the value of visual raw data and its relationship to scholarship for constructing debates; an entrenched form of encounter between subject and author which can construct a median position from which, we the viewer can judge the legitimacy and valence of their engagements through evidence, and perhaps even levels of our own considerations of a malaise that has plagued our societal framework.

As Nithya Natarajan notes in her review of the exhibition, ‘following India’s turn to economic liberalisation in 1991, successive Indian governments have sought to highlight the country’s apparently unprecedented economic success, understood almost exclusively in terms of its growing GDP…Yet, as critical scholarship has shown, this growth is characterised by, and in fact relies on, incredibly low levels of job creation, and a concurrently proliferating informal sector, with more than 90 percent of all Indian laborers being employed outside the formal sector (Harriss-White and Gooptu 2001).’ Her words are inspired by the work of contributors to the book like Jens Lerche’s research on the Dalit women of UP; or the Oraons and Mundas of Jharkhand researched by Alpa Shah herself.

The Indian growth story is thus one of poor and low-paid work, of exploitation and discrimination, and of entrenched poverty for large swathes of the Indian population.

The groundwork accomplished for the book and the exhibition present a counter-narrative to the dominant and ongoing media representation which has lauded campaigns such as ‘Make in India’, that explicitly position India as an attractive investment hub by highlighting its cheap labour economy. This rendering of the notion of progress ignores the exploitation, oppression and marginalisation of Dalits and Adivasis, India’s low caste and tribal communities that carry the weight of the economic growth, but enjoy little of its fruits. These communities have little protection from legal systems and enforcement agencies (as Sandhya Fuchs investigations intimate) that could allow the castes and tribes to avail of certain protections and safeguards (1989 and 2013 being hallmark years) – be they constitutional or simply humanist terms on which individuals in society should be treated.

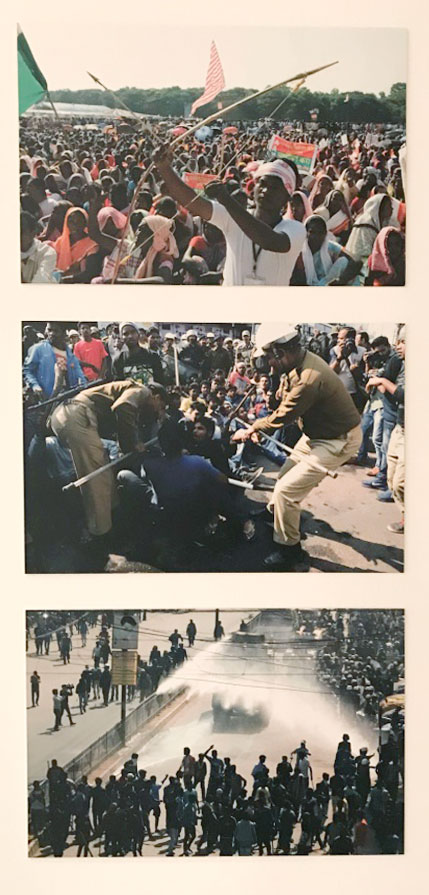

Presenting a pan-Indian ambit, the researchers for the book travelled to various parts of the country, living in trying circumstances, and sharing findings in order to draw out their own inferences in a complementary way. For example, Dalit and Adivasi labour in the tea plantations of Kerala researched by Jayaseelan Raj; Vikramaditya Thakur’s work on Bhil Adivasis of Maharashtra; Dalel Benbabaali’s work on Koya Adivasis and Madiga Dalits of Telangana; Brendan Donegan’s work on Dalits in the chemical industries in Tamil Nadu; or Richard Axelby’s work on Gaddis and Gujjars in Himachal Pradesh, all present searing testimonies on the ill-fated realities of privatisation and the historical disjunctures that continue to play out. As R. Srivatsan says in his review of the book, emergent discussions around the neo-liberal mainframe can mistakenly seek ratification in the trickle-down effect, rather than highlighting ruptures and deep-seeded faults in very hierarchised structure of caste; the book undermines the argument that caste barriers will either weaken or disappear as capitalist social relations proliferate. The exhibition also dislodges a rampant status quo by highlighting activist or protest imagery from various parts of the country, and often the violent repression met by such resistance against the state.

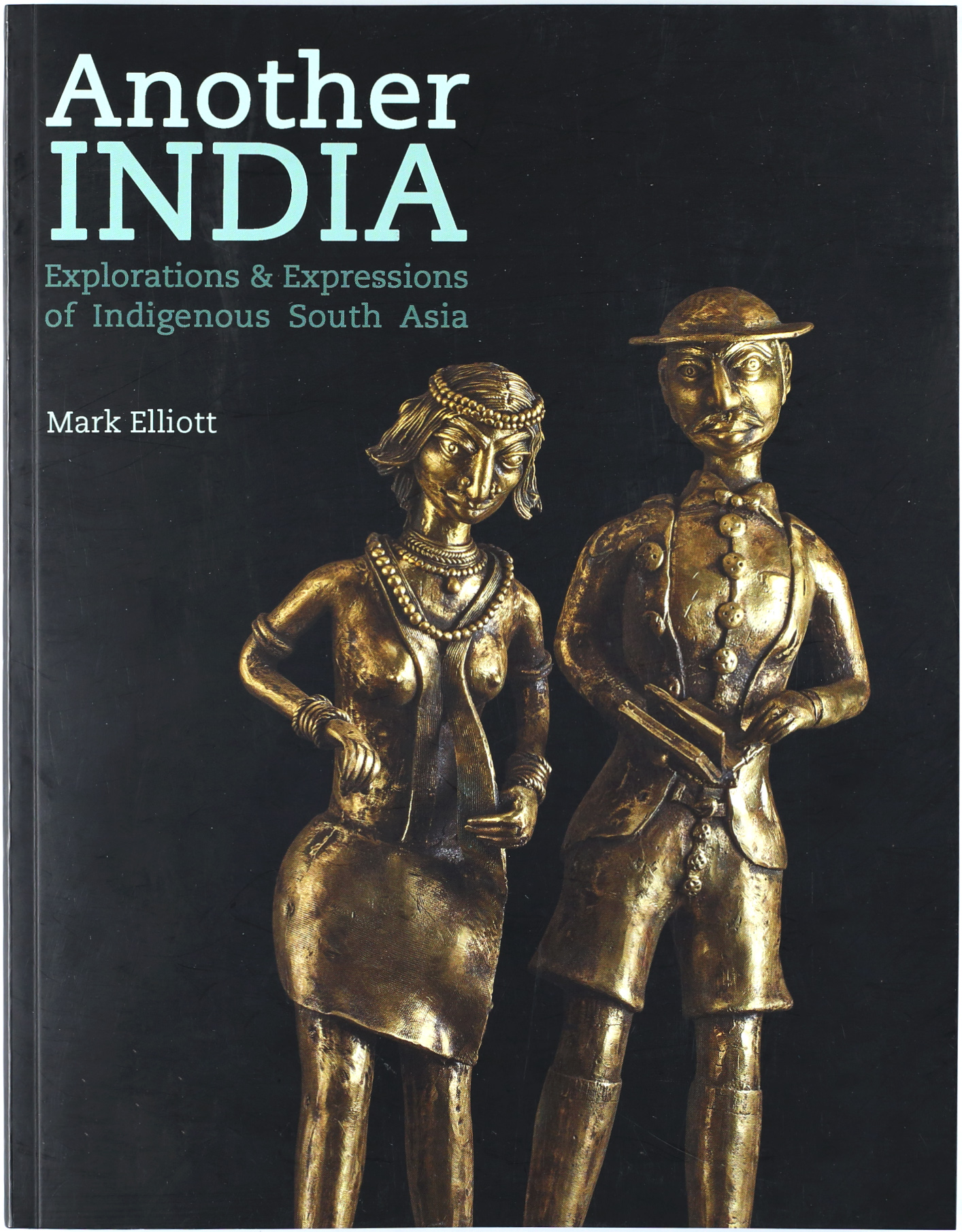

In the past few years, there have also been other voices which reclaim exhibition spaces in order to put forth a stratum of representation that has been elided for far too long: Another India: Explorations and Expressions of Indigenous South Asia held at Cambridge in 2017 (8 March 2017- 22 April 2018) curated by Mark Elliot (MAA, Cambridge), presented buried artefacts and photographs of the Cambridge Museum archives and newly commissioned art works (supported by the Art Fund) from Adivasi communities which posed questions around production, context and the representation of India. The supporting catalogues/visual books for both, Another India and Behind the Indian Boom were published by the Adivasi press, Adivaani.

Exhibition view (Cambridge)

Exhibition view (Cambridge)

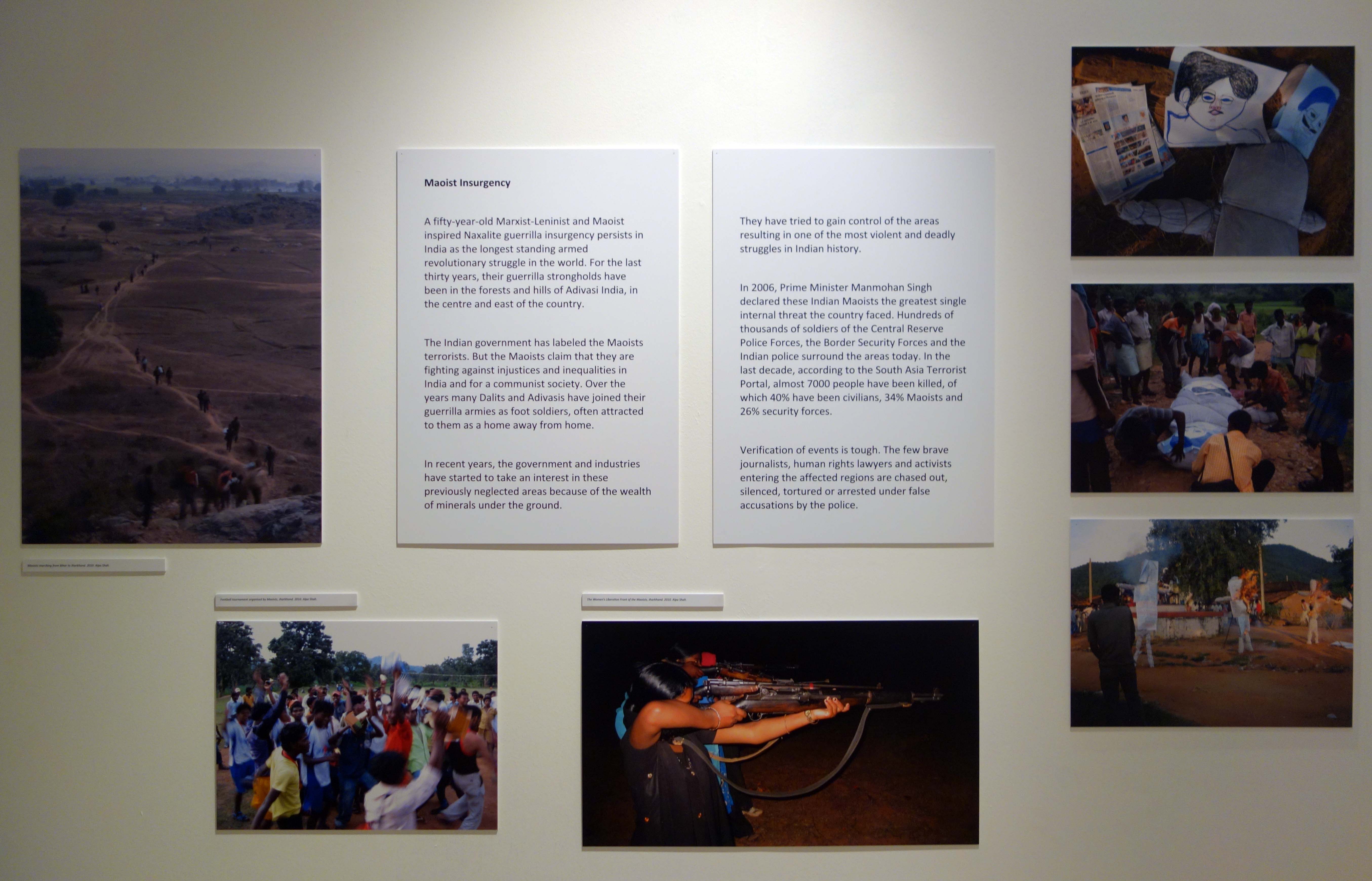

Another exhibition that has presented some illumination on marginalised communities through photography was Dalit: A Quest for Dignity. In 2016, the Nepal Picture Library in Kathmandu organised a photo exhibition with its partners at the Patan Museum there, which included around 80 images spanning 66 years from approximately 20 sources, all highlighting the Dalit experience in Nepal. According to the official 2011 census of Nepal, the country has a Dalit population of approximately 3.6 million people, or 13.6 percent of the total population. The Dalit community in Nepal consists of 26 castes—seven of which are Hill Dalits and 19, Madhesi Dalits. The image in the exhibition’s poster below shows TR Bishwakarma, a pioneering Dalit activist from the 1950s, delivering a speech on the occasion of the first unified civil code of Nepal, released in 1963. Bishwakarma, however, in time came to lead a more radical path with the Nepali Maoists, bringing us back to Behind The Indian Boom, which also explores how the context for the armed revolutionary struggle in form of the Naxalite guerrilla insurgency has persisted in India, how Adivasis have affiliated with the armed insurgency, and how they have been seen as a cause of internal threat to security, especially since 2006. As the exhibition highlighted, the Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh called the Maoists the single greatest threat to internal security causing the military to take over the Adivasi forests of central and eastern India.

The persisting historic inequality is explicitly seen through the works presented in Behind the Indian Boom, but perhaps what the exhibition highlights is the urgent need for a community to unite against these injustices. Of course, we can always talk about agency, voice and objectivity in photographs; raise questions about returning to the field, problems of overtly aestheticising it for the commercial art world, or parachuting in and out for a news gathering organisation. However, the daunting statistics presented which state that the violence reported against marginalised groups has increased over 74% in the last decade should above all make us ask whether that escalation has been proportionately addressed with an increasing vigilance in display practices and curatorial exercises within institutions, national or regional, during that time…

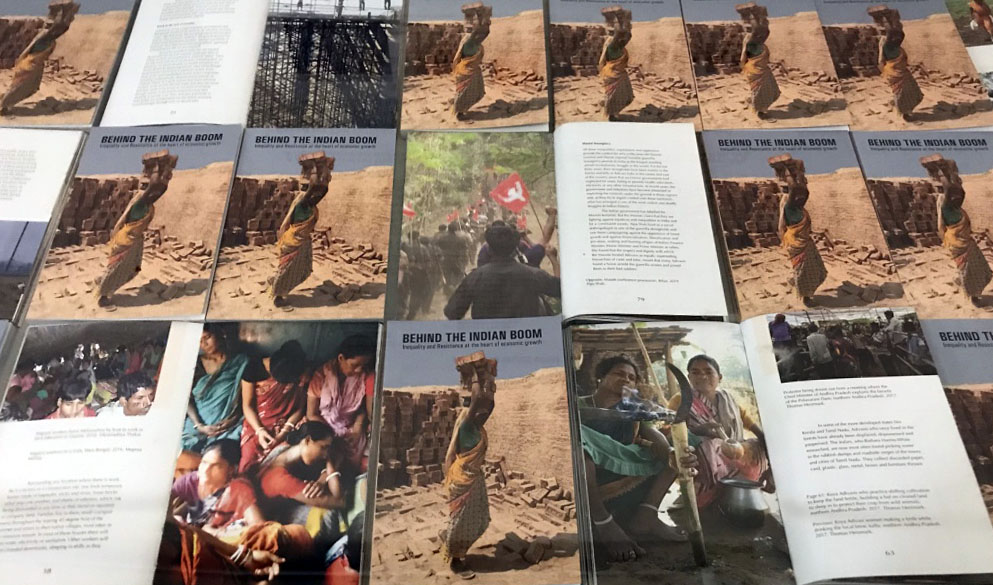

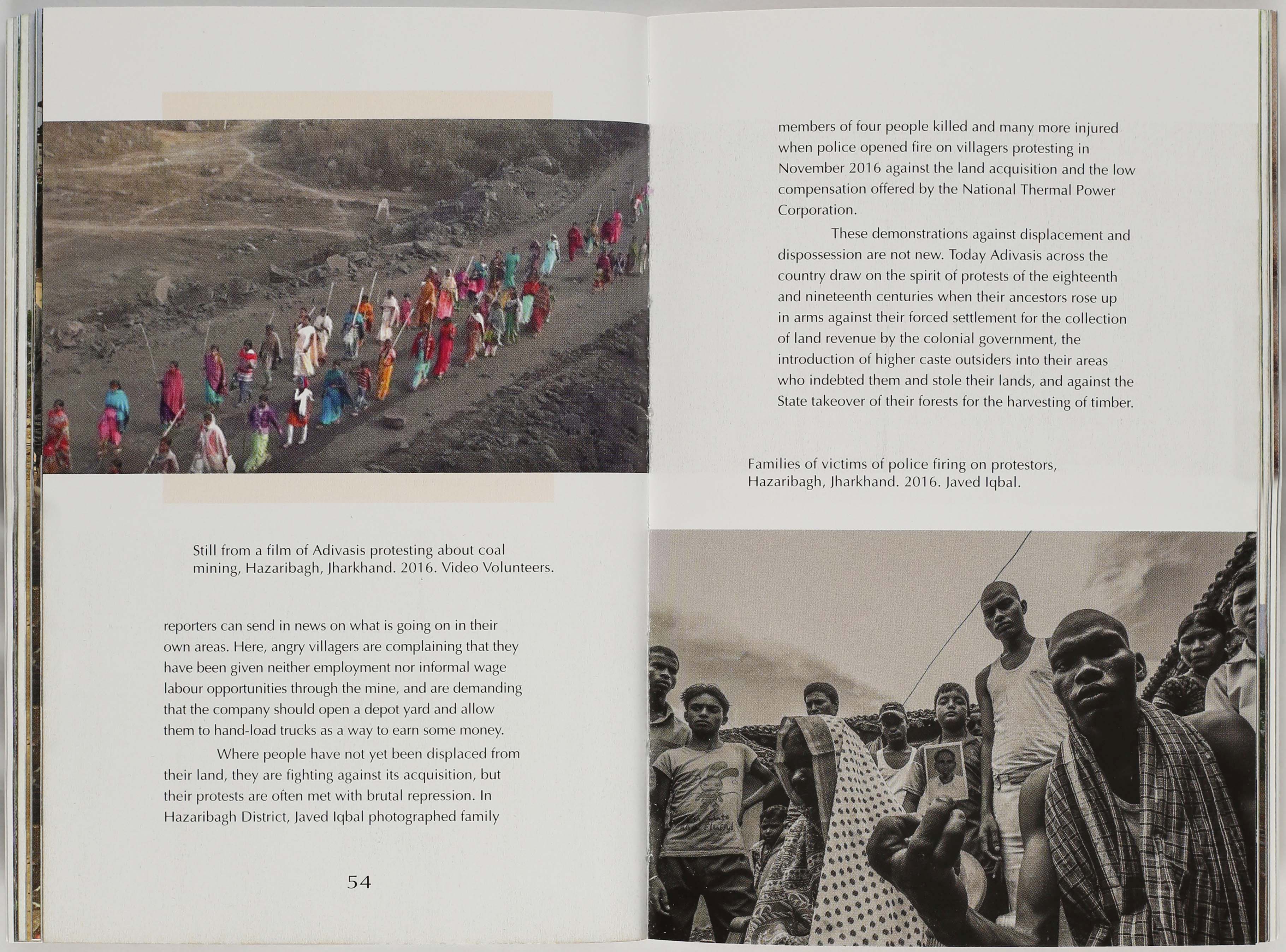

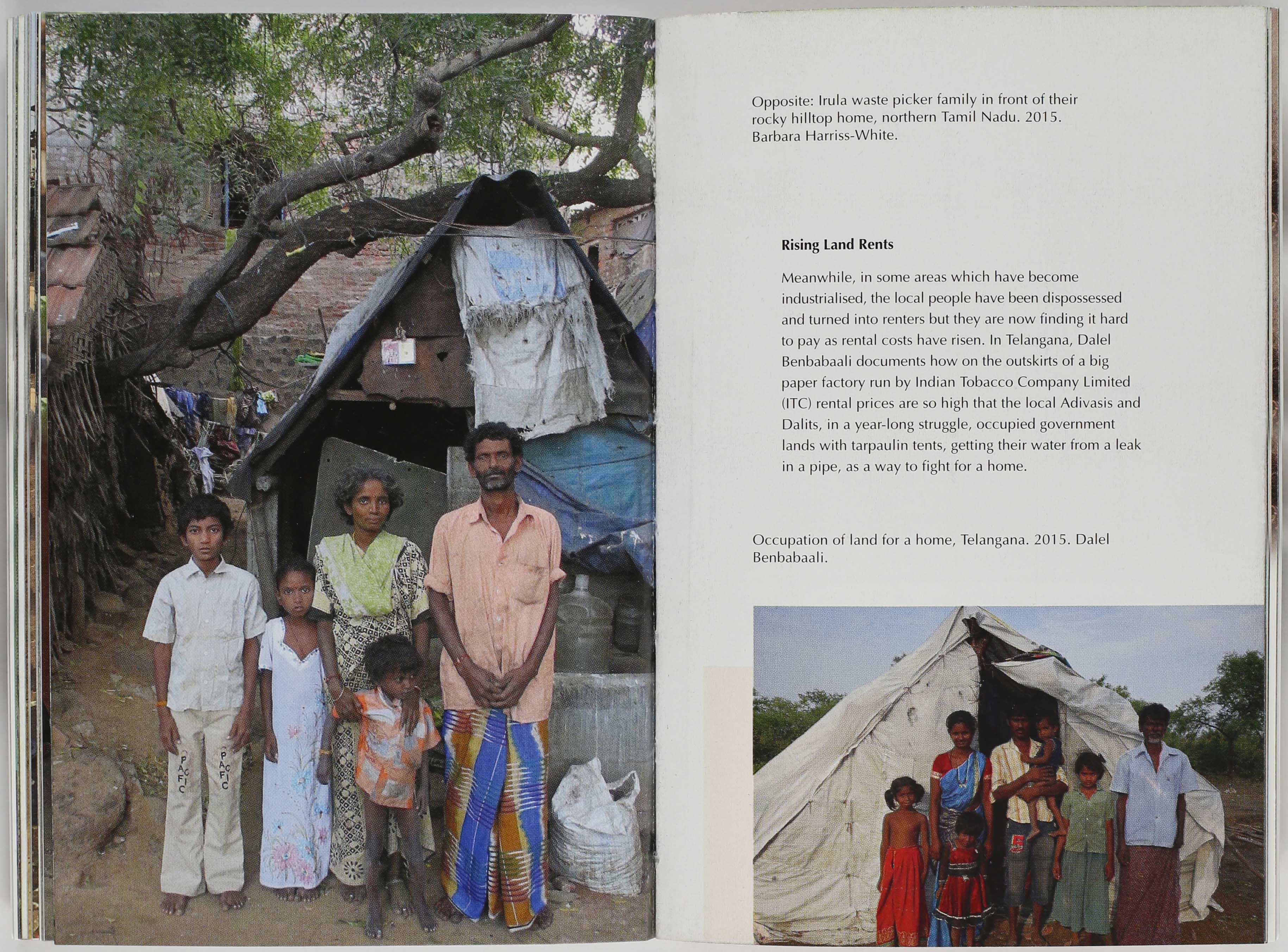

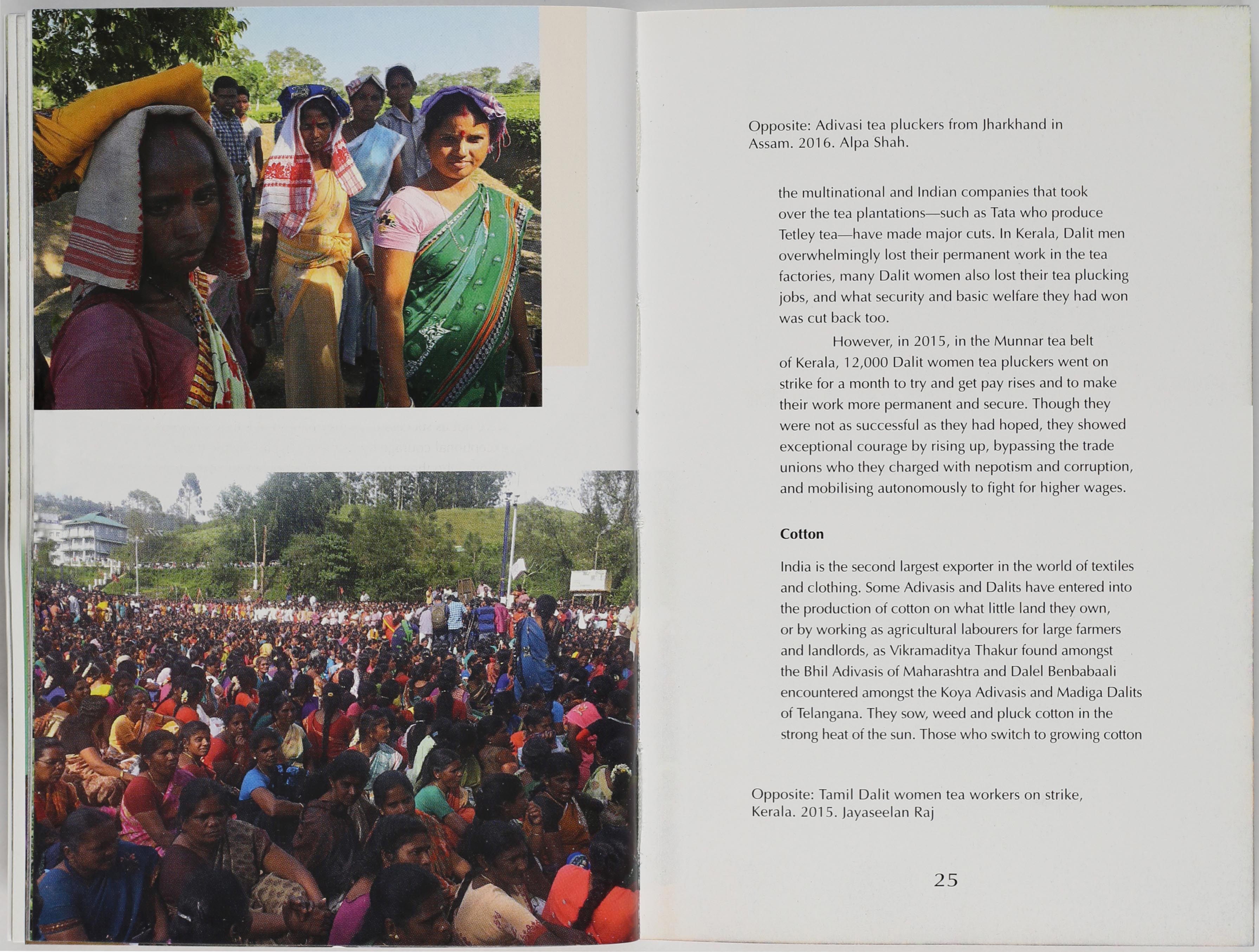

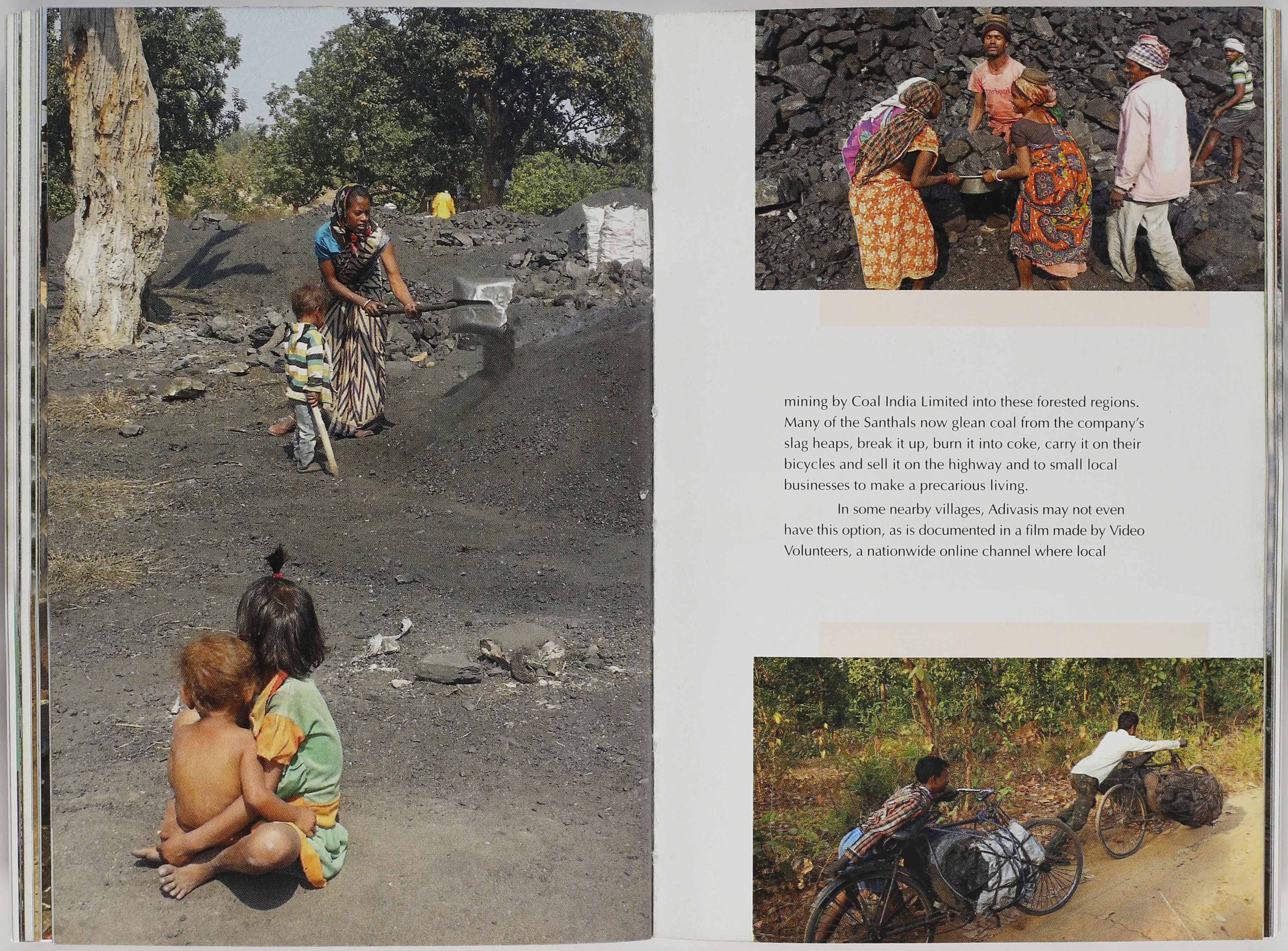

Spreads from the exhibition booklet

Spreads from the exhibition booklet

This week, in an interview with Dr. Alpa Shah, we discuss the inception and motivations of this project, the role of photography as an anthropological tool and the integral question—Whose growth is it?

Exhibition view (Brunei Gallery)**

Exhibition view (Brunei Gallery)**

Ground Down by Growth and Behind the Indian Boom, are interlinked or complimentary projects: One a publication and the other an exhibition. What were some of the challenges in realising such a researched based publication in exhibition form?

The book and the exhibition grew out of our wider LSE Anthropology Programme of Research on Inequality and Poverty which explores how and why Adivasis and Dalits remain at the bottom of the Indian social and economic hierarchy. The two outputs are aimed at different audiences. The book – Ground Down by Growth (authored by seven of us) – will interest specialist audiences who are already concerned about issues of inequality, poverty, minority discrimination, oppression and India. The exhibition – Behind the Indian Boom, which has more than 30 contributors – was also for those who may have no background at all in the issues concerned and who may even think that all is shining in India, that caste and tribe are things of the past, and that economic growth has been good for everyone. It seeks to challenge these myths through a visual narrative focusing on the experiences of India’s Adivasis and Dalits. To give a flavor of the exhibition to those who missed it and might have liked to see it (especially in India), we also produced a small photo booklet to accompany the exhibition which was published by the Adivasi press, Adivaani.

Book Cover, OUP 2018

Display of exhibition booklets

Display of exhibition booklets

Has photography been used as an anthropological tool by the researchers involved in the exhibition? What was the research methodology deployed?

There’s a long history of visual anthropology but none of our researchers were trained as visual specialists. Most of the photographs were taken on phones or whatever devices the researchers happened to have at the time of conducting ethnographic fieldwork. While the majority of the material was that of anthropologists associated with our Programme of Research, we also included some work from local Indian filmmakers and photo journalists – such as Javed Iqbal and Manob Chowdhury – who were working on similar issues in the sites of our field research.

Spreads from the exhibition booklet

Spreads from the exhibition booklet

Apart from more than 200 photographs, there were also seven video and audio installations – for instance, a short film on women construction workers produced for the ILO by Margaret Dickinson with students she trained in Bhilai; a BBC Radio 4 report for From Our Own Correspondent on Adivasis displaced by Salwa Judum presented by me, and a film from Video Volunteers made by local people in Hazaribagh, Jharkhand showing the devastation coal mining had caused to their communities.

Construction workers in Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, Ajay T.G.

Construction workers in Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, Ajay T.G.

Exhibition view**

Exhibition view**

Our primary purpose was not aesthetic but to enable the messages of our research to reach a wider audience through visual means. We wanted to maintain some of the raw quality of the fieldwork in our visual story – we didn’t frame the photos, we presented them as they may appear in a sketch-book – for a grassroots, bottom-up perspective of what was happening to Adivasis and Dalits in contemporary India.

Spread from the exhibition booklet

Spread from the exhibition booklet

Exhibition view**

Exhibition view**

Over what span of time was the work done and how has the exhibition been sectionalised?

The research has been done over many years. Some contributors have been doing fieldwork in India for several decades and others are PhD students who are starting out. What unites the core contributors is that their fieldwork is based on living with the communities they researched for at least a year, usually much more.

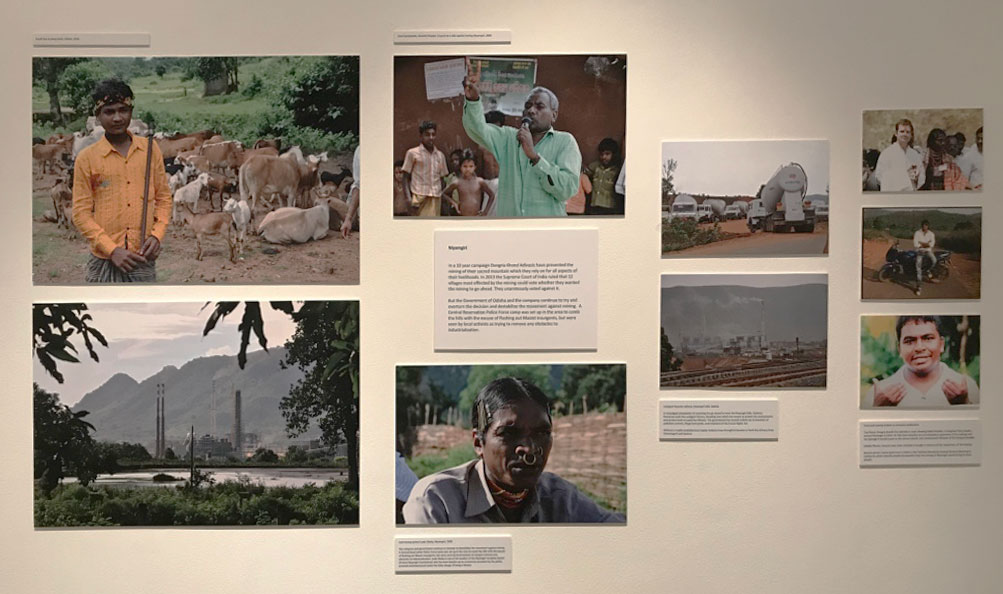

The exhibition explores the precarious conditions of work and everyday struggles of Dalits and Adivasis as they produce different global commodities from tea to cotton, build the infrastructure sustaining Indian economic growth from construction to dams, and are dispossessed from their land for the extraction of mineral resources and other development programmes. The different sections of the exhibition show how Adivasis and Dalits are a source of cheap labour from which much of the world economy benefits, and some of the lands on which they have lived for generations are today major crucibles of global industry. They emphasize how social oppression is part and parcel of this process of neoliberal capitalism. Importantly, the exhibition also highlights people fighting back, through various forms of protest, against the situations they find themselves in.

Spreads from the exhibition booklet

Spreads from the exhibition booklet

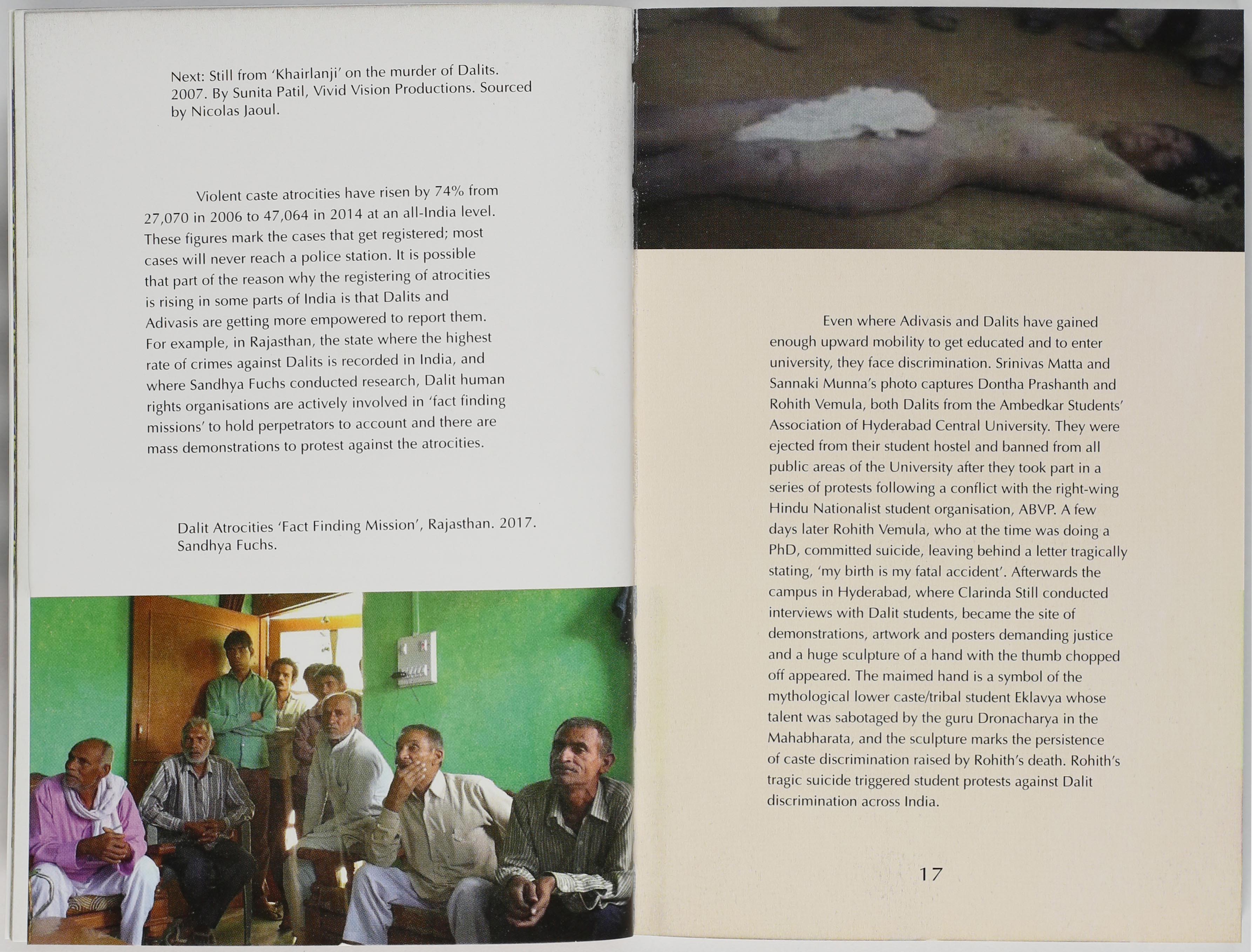

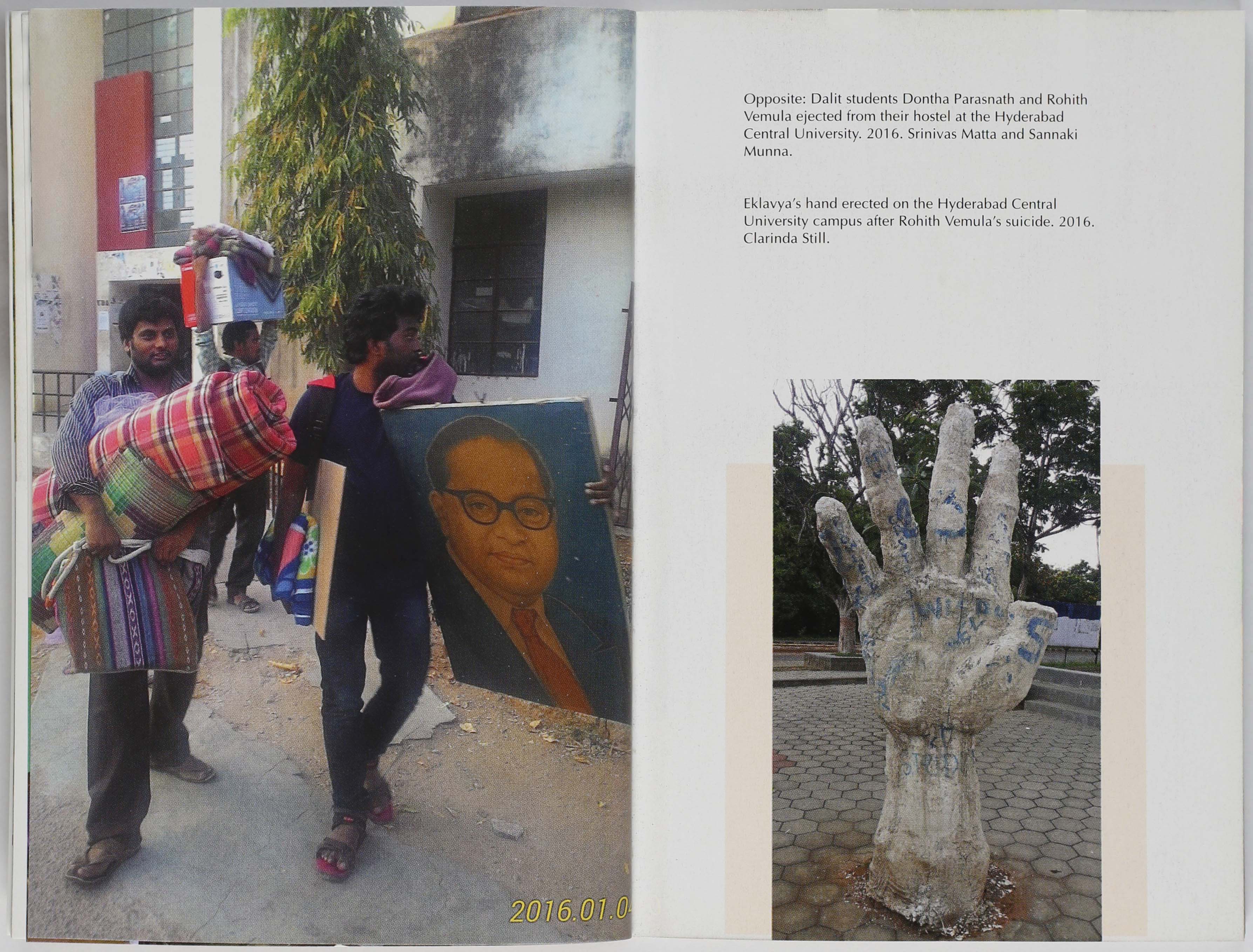

Welcome to India, ‘the land of opportunities’, ‘where money grows’, is how the exhibition started; a message in stark contrast to what followed. The history of Dalit and Adivasi marginalization was introduced through a series of photos and a clip of a film on the 2006 Khairlanji massacre of Bhotmange Dalits, a short film on contemporary manual scavengers in Delhi’s outskirts, and – what many visitors saw as one of the highlights of the exhibition – a nine foot reproduction of Eklavya’s dismembered hand that appeared on the Hyderabad campus as part of the protests against the discrimination faced by Dalits after the 2016 suicide of the Rohith Vemula.

Adivasi marginalization is often different to that of Dalits and has resulted in their retreating into India’s hills and forests, leading a rich autonomous cultural life as subsistence farmers and shifting cultivators. This wealth of Adivasi communities was displayed across a large wall through pictures of the daily lives of Oraons, Mundas and Birhors of Jharkhand, the Koyas or Andhra Pradesh, the Bhils of Maharashtra and the Gaddis of Himachal. But the largest sections of the exhibition showed the contemporary exploitation of Adivasis and Dalits as the most precarious of labour in India’s informal economy – including a central room on seasonal labour migration – and the ways in which Adivasi lands were being taken away from them for mining coal, iron ore and bauxite for national and multinational corporations. There was also a section on pollution and health degradation. Protest emerged everywhere – from the Dalit women tea workers strike to the Dongria Kond fight against the mining of their sacred Niyamgiri mountain. The exhibition ended with the Naxalite insurgency and the brutal counterinsurgency operations that have cost so many lives across the country.

Exhibition views*

Exhibition views*

What do you feel are some of the groundbreaking facts that emerge from the research/exhibition? Could you reference some examples?

We show that global capitalism often entrenches social inequality and this happens through at least three interrelated processes. First, through inherited inequalities of power in which historically dominant groups and the state control the adverse incorporation of Adivasis and Dalits in the capitalist economy. Take for example, the Tamil Nadu chemical factories or a paper factory in Telangana. The people who have colonized the best jobs in industries are the erstwhile dominant castes who historically owned the land. And those who have the most precarious and worst jobs on zero hours contracts – whether it is handling polluted animal bones to make gelatin or toxic materials to make paper – are the landless Dalits. Second, through the super-exploitation of casual migrant labour, whereby local labour power is undercut by a more vulnerable workforce, enabling capital to fragment the overall workforce and therefore better control and cheapen it.

So, for instance, whether it is the Kerala tea plantations or the Tamil Nadu chemical factories, when local Dalit labourers resist their exploitation, their protest is broken up by Adivasis being brought from eastern India to replace them on even worse terms and conditions of work. Third, through conjugated oppression in which discrimination and stigmas based on caste, tribe, gender and region are all a part of, and intertwined with, exploitative class relations.

Exhibition view*

Exhibition view*

Exhibition view**

Exhibition view**

How was the exhibition received in the UK?

The exhibition was extremely well-received in London. We had more than 10,000 visitors at the Brunei Gallery over two months. Some were students, others those on the museum mile as tourists in London (the exhibition was part of the Bloomsbury festival), but many were also from the Indian diaspora – something we are particularly happy about as the dominant idea among NRIs is that all is glorious in contemporary India. In fact, a questionnaire we conducted showed a significant shift in people’s opinions on caste being a thing of the past and on economic growth being good for everyone. The exhibition and book were covered by various media outlets including BBC World Service Weekend, BBC Asian Network, the Hindu, Asian Age, Focaal and the Italian Il Manifesto. The interest generated meant that we took the exhibition to the LSE Atrium Gallery for another month of exposure in London. Now some interested people in Italy are planning its move to Turin in May 2019.

Exhibition views*

Exhibition views*

How do you think the exhibition/publication will be received in India? What are some of the challenges you envision on that front?

Although this is not the mainstream dominant narrative on India, many people know these stories and the significance of the messages we tell and are of course working on the same issues themselves. So while the exhibition and publications might challenge those who want to believe and show that India is shining, it will also be of solidarity to those who are tirelessly working on the ground in India and are affected by similar issues.

Exhibition view. Courtesy: LSE Arts Atrium Gallery

Exhibition view. Courtesy: LSE Arts Atrium Gallery

*Photos by Alpa Shah / **Photos by Dalel Benbabaali

Alpa Shah is Associate Professor of Anthropology at LSE where she leads the Programme of Research on Inequality and Poverty. She is the author of ‘Nightmarch: Among India’s Revolutionary Guerrillas’ to be released in India by Harper-Collins this year, ‘In the Shadows of the State: Indigenous Politics, Environmentalism and Insurgency in Jharkhand, India’, co-author of ‘Ground Down by Growth: Tribe, Caste, Class and Inequality in 21st Century India’, and was one of the curators of ‘Behind the Indian Boom: Inequality and Resistance in India’.

Comments