A History from Below: Prof. Marianne Hirsch on memory and photography

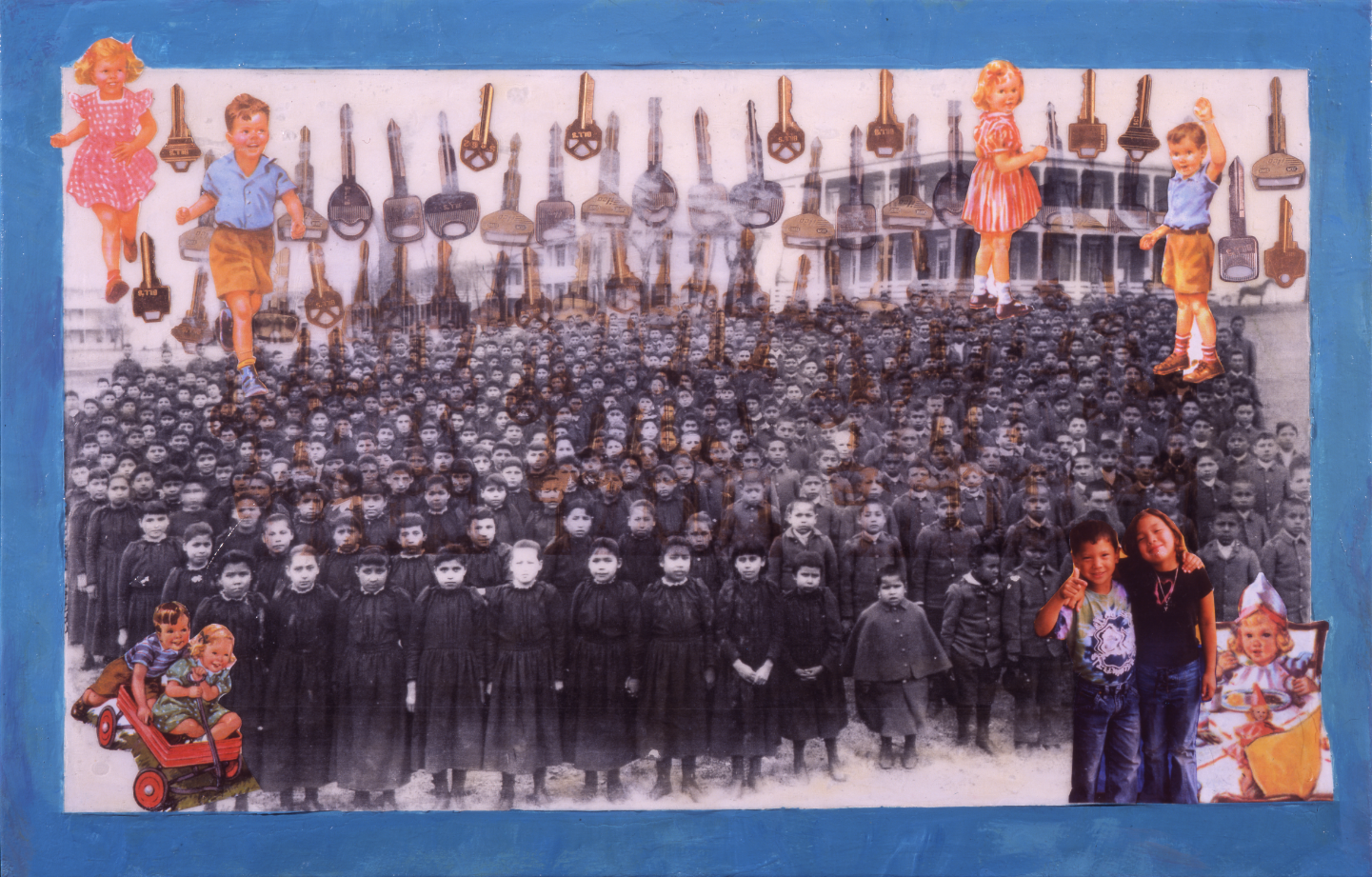

Steven Deo, When We Become Our Role Models No. 2, 2004. (Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College Collection)

This week we had the extraordinary opportunity of interviewing and engaging with the pioneering scholarship and continuing work of Prof. Marianne Hirsch, who is William Peterfield Trent Professor English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University as well as Professor at the Institute for Research on Women, Gender, and Sexuality. Her long and established trajectory combines feminist theory with memory studies, particularly the intergenerational transmission of violence, and the galvanised urgency in reconsidering the predetermined roles of family to provoke the need for change. Her most recent work also looks to artworks, and how certain practitioners speculate ways of being vulnerable and moved in order to come to realisations about past events in unpredictable ways.

Prof. Hirsch talks about the continuing presence of the past in memory. Video Courtesy of the Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry.

In 1992, it was Prof. Hirsch who introduced the term “postmemory,” a concept that has subsequently been scrutinised, theorised, deployed and cited by countless researchers, pedagogues and artists across the world, working around the interconnections between objects, histories, affect and psychosocial phenomena such as trauma. Postmemory describes a relationship that the “generation after” bears to the personal, collective, and cultural contentions of those who came before, emphasising the need for reading, listening and other modes of receptivity. To this generation, these are experienced by means of anecdote and recollection – images, and events among which they grew up – however these facets of memory are absorbed so deeply that they seem to constitute lived and felt moments in their own right – an epigenetic inheritance. Hirsch goes on to explain over many publications, the complex entanglement of past, present and future contained within the idea of the embodied nature of violence and ways in which we may practice responsibility –

Postmemory’s connection to the past is actually mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation.

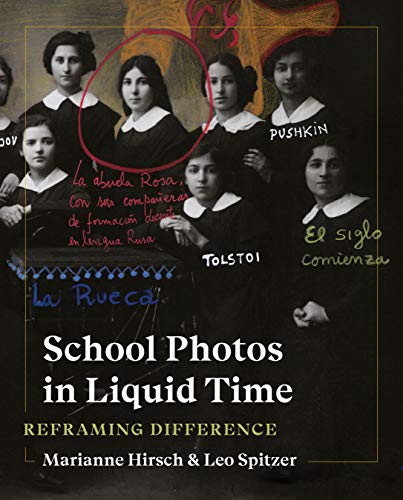

Some of Hirsch’s notable publications include School Photos in Liquid Time: Reframing Difference, co-authored with Leo Spitzer (University of Washington Press, 2020); The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (Columbia University Press, 2012); Rites of Return: Diaspora, Poetics and the Politics of Memory, co-edited with Nancy K. Miller (Columbia University Press, 2011); Ghosts of Home: The Afterlife of Czernowitz in Jewish Memory, co-authored with Leo Spitzer (University of California Press, 2010); and Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory (1997).

1. There are so many dimensions to memory that you highlight through your publications – every context/social situation can trigger a set of memories, but what are some of the challenges of deploying this to revive or revise past events? What are the benefits and what are the pitfalls in using the term memory to refer to how the past is transmitted and lived in the present, and how it points to the future?

It is well known that many historians resist the authority of individual recollection and discount it as evidence. Yet, I would say that memory captures the intimate, embodied, even visceral dimensions of the past’s presence.

It captures its transmission in intimate settings, like the home or the family. Memory, one could say, is history from below. Collective or cultural memory brings forward the stories and experiences of those who are left out of grand historical narratives, contesting, complicating and disseminating those narratives and their hegemony. Small stories, affectively felt and transmitted, add up to more textured, more granular, and more inclusive – yet always also incomplete – visions of the past. Memory needs to be supplemented with other sources – written, visual, aural and oral accounts. These archival sources, however, also always need to be accompanied by a consciousness of how archives are instituted, what they include and what they exclude.

Lived and reanimated in family or group contexts, memories become the bases of group identity and belonging. When that identity is built around past injury, however, it can be mobilised for reactionary as well as progressive ends; it can serve rightwing causes and revive century-old grievances. And those of us who have been building a field we think of as “memory studies” in the interests of redress, inclusivity and social justice have had to become more vigilant about the uses and misuses of memory as a notion around which to organise our thinking and our activism – more attentive to the pitfalls you raise.

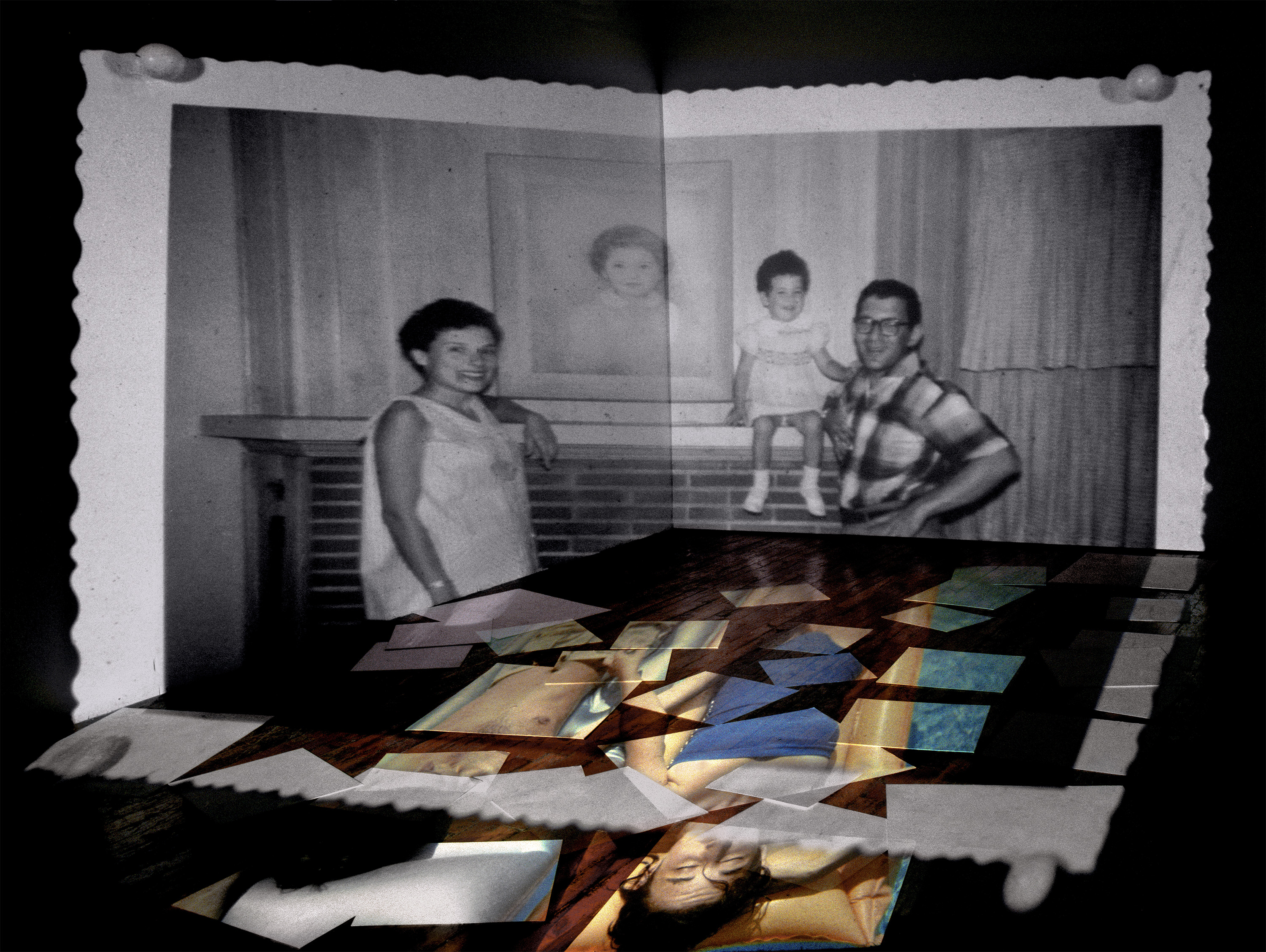

Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory by Marianne Hirsch( Harvard University Press, 1997)

2. What are some of the important conversations you have had, or social events and political timelines that led you to arrive at the concept of “postmemory”? Are you able to lend an autobiographical sketch to your pedagogical interest and have you noticed that your own memories are prone to change?

Images play an important role in the formation of memory and the consolidation of group identities. I first began working on memory in my book, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory (1997). I was trained in literature, Comparative Literature, specifically, and I turned to feminism just as I was finishing my graduate training and began teaching. As a feminist literary scholar, I was particularly interested in examining the family as a site of the development of gender formation and hierarchy, of heteronormativity, and of generation. My book The Mother/Daughter Plot (1989) explored how narrative structures are determined by the idea of the family, that is, by certain notions of childhood, of subject-formation, of development and generation and of how all these are gendered.

The Mother/Daughter Plot: Narrative, Psychoanalysis, Feminism by Marianne Hirsch (1989)

“Fragments” (1987) by Lorie Novak. Image from the book Family Frames.

In Family Frames, I came to photography with the same questions. I realised that in the late twentieth century family narratives are often visual and, specifically, photographic. Family photos shape family memories, but only certain aspects of family life are photographed: the genre is tightly circumscribed. I realised that in order to account for the power these utterly conventional images hold for most of us, whether we have happy families or difficult ones, I had to read memoirs and novels that included and discussed family photos, and I had to study the work of photographers who either took pictures of their own families, or who reframed family photos thus also commenting on this genre. I not only studied their work, but I also co-curated an exhibition on “The Familial Gaze” at the Hood Museum of Art in 1996 and edited a collected volume The Familial Gaze published by the University Press of New England in 1998, inviting a number of scholars and artists to join this exploration into family photography. This work is at the juncture of photography studies as ‘ideology critique’, prevalent in the 1980’s, on the one hand, and the more recent ‘affective turn’ in volumes such as Feeling Photography, on the other.

Feeling Photography edited by Elspeth H. Brown, Thy Phu (Duke University Press, 2014)

Clearly, however, family photos are not exclusively private just as the family is embedded in the social and the political in every possible way. Part of my exploration also included writing about my own family photos. Mine might look like yours, but only mine evoke strong feelings in me – I project so much unto them. And as I was doing what at first were writing exercises, I came to see the important connection between photography and memory, both personal and collective. Small square pieces of paper with jagged edges carried with them whole worlds from my own past, but also from a past that preceded my birth.

In my case, those images came from a lost world – the pre-World War Two and pre-Holocaust world of Jewish Central Europe where my family survived the war. Looking at them, I realised how much they revealed and how much they concealed, how they opened only a very small window into a world that had been transmitted to me very powerfully. Sometimes, I felt that what I knew about my parents’ past – knowledge congealed in and also liberated from small black and white images by their stories and behaviours – was more vivid than my own childhood memories.

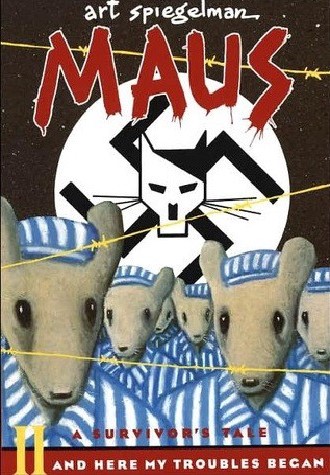

All this came clear in the late 1980’s when I read two important books, Maus by the graphic artist Art Spiegelman, a graphic memoir about his father’s survival of the Holocaust in Auschwitz, and Beloved, Toni Morrison’s novel about the multi-generational transmission of enslavement. In both cases, the traumatic past was transmitted with similar force to descendants whose lives came to be dominated by events that preceded their birth, and who felt that unlived past as a form of “memory.” This is how I first developed the notion of postmemory in an article about Maus (in the journal Discourse, 1992/3) and that article was specifically generated in response to Spiegelman’s reproduction, in his graphic animal fable in which Jews are portrayed as cartoon mice, and Germans as cartoon cats, of three actual photos of his mother, his father, and his murdered brother Richieu, whom he had never known. These family photos disrupted the grids of the graphic memoir, they burst the frames and practically break out of the pages of the second volume of Maus. This is how postmemory of trauma and family photographs can disrupt the present, and the linear temporal progression we have come to expect between past, present and future.

Cover from the graphic memoir Maus (II) by Art Spiegelman (Pantheon Books, 1991)

Family Frames was followed by three books that further elaborated the notion of postmemory, while also doing postmemory work: the history of the city my parents came from, Czernowitz, Ghosts of Home: The Afterlife of Czernowitz in Jewish Memory, co-authored with Leo Spitzer (2010), The Generation of Postmemory (2012) and, just this year, School Photos in Liquid Time: Reframing Difference, also co-authored with Leo Spitzer (2019). Each of these works uses vernacular photographs, as well as the work of writers and artists who reframe them, as companions with which to think about and to perform memory acts. Each is written in hybrid, I would say trans-or post-disciplinary form – scholarly analysis, criticism, theory and memoir, all interspersed with one another. In these books, family photos, street photos, school photos – whether personal or institutional – become historical actors that embody memory and help to write history.

Ghosts of Home: The Afterlife of Czernowitz in Jewish Memory by Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer (University of California Press , 2010)

3. What are some of the key events (and images therein) in contemporary culture that you feel can most keenly be used to illustrate the political climate today?

I’d like to respond to your question by focusing on my latest book, co-authored with Leo Spitzer, School Photos in Liquid Time and the exhibit we co-curated at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, “School Photos and Their Afterlives.” The exhibit closed prematurely in March due to the Coronavirus pandemic, but the issues it brings to visibility are ever more relevant this fall. This project speaks directly to urgent concerns – about rights, citizenship, inequality, racism and xenophobia – that we share across the globe. And it also speaks directly to present-day decisions about opening schools and the risks both of in-person learning, and of also how children’s isolation from one another have come to seem ever more intransigent. In the United States, at least, this moment has underscored how social and economic inequality shape educational opportunities.

School Photos in Liquid Time: Reframing Difference by Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer (University of Washington Press, 2019)

School photos can be found almost everywhere across the globe and they appear very early in the history of photography. And yet, historians and critics of photography have virtually ignored them, perhaps because they are so strictly conventional. Many artists from around the world, on the other hand, have engaged, reframed and animated school photos and they have thus opened them for our closer scrutiny. They helped us discover the important social and ideological functions school photos have played, and continue to play, throughout the world. These functions emerge with particular force in times of crisis and extremity—persecution and discrimination, war and genocide.

Our book and exhibit build on the insight that technical innovations in photography in the second half of the 19th century coincided with the development of state-accredited education in Europe, in the Americas, and in their colonies. The truth, however, is that the commonality and integration that traditional school photos visually exhibit are deceptive.

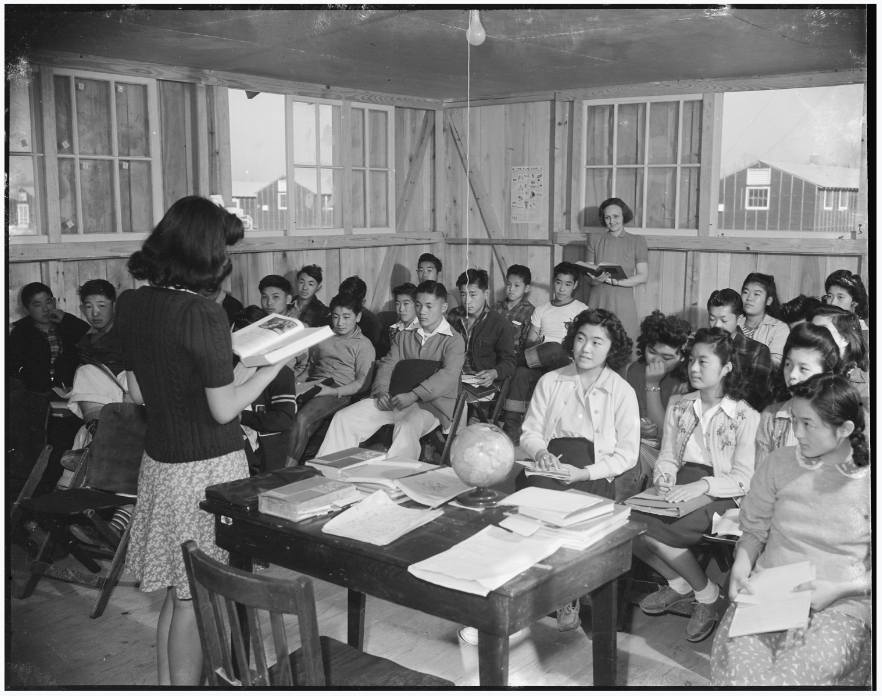

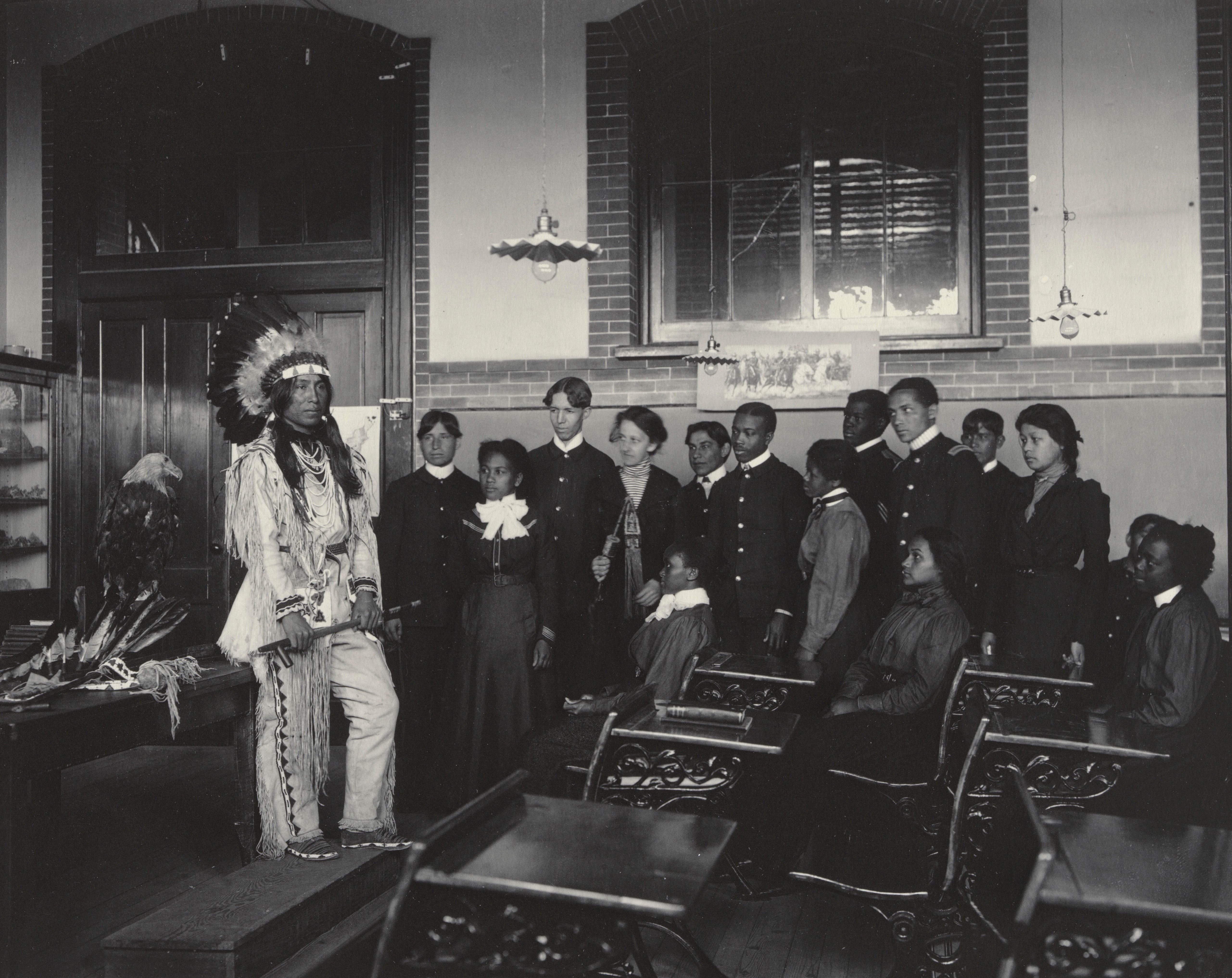

In their efforts to manage religious, ethnic, national and racialized differences in their heterogeneous populations, imperial, colonial and state institutions in Europe, in North America and in Euro-American colonies successfully used school photography to further their assimilationist and socially transformative ideologies, furthering the supremacy of white Christian ways of being and thinking.

School photos participate in the creation of national and imperial subjects well educated in the hierarchies and practices of inclusion and exclusion that suffuse social life, as well as of social “others” who, in times of extremity, can become subject to forms of persecution and separation that can lead to sanctioned violence and murder. As a technology of modernity, school photography thus provides visual evidence of official attempts to minimise and disguise, or, at other times, to maximise the social differences that shape communal life both inside and outside the school.

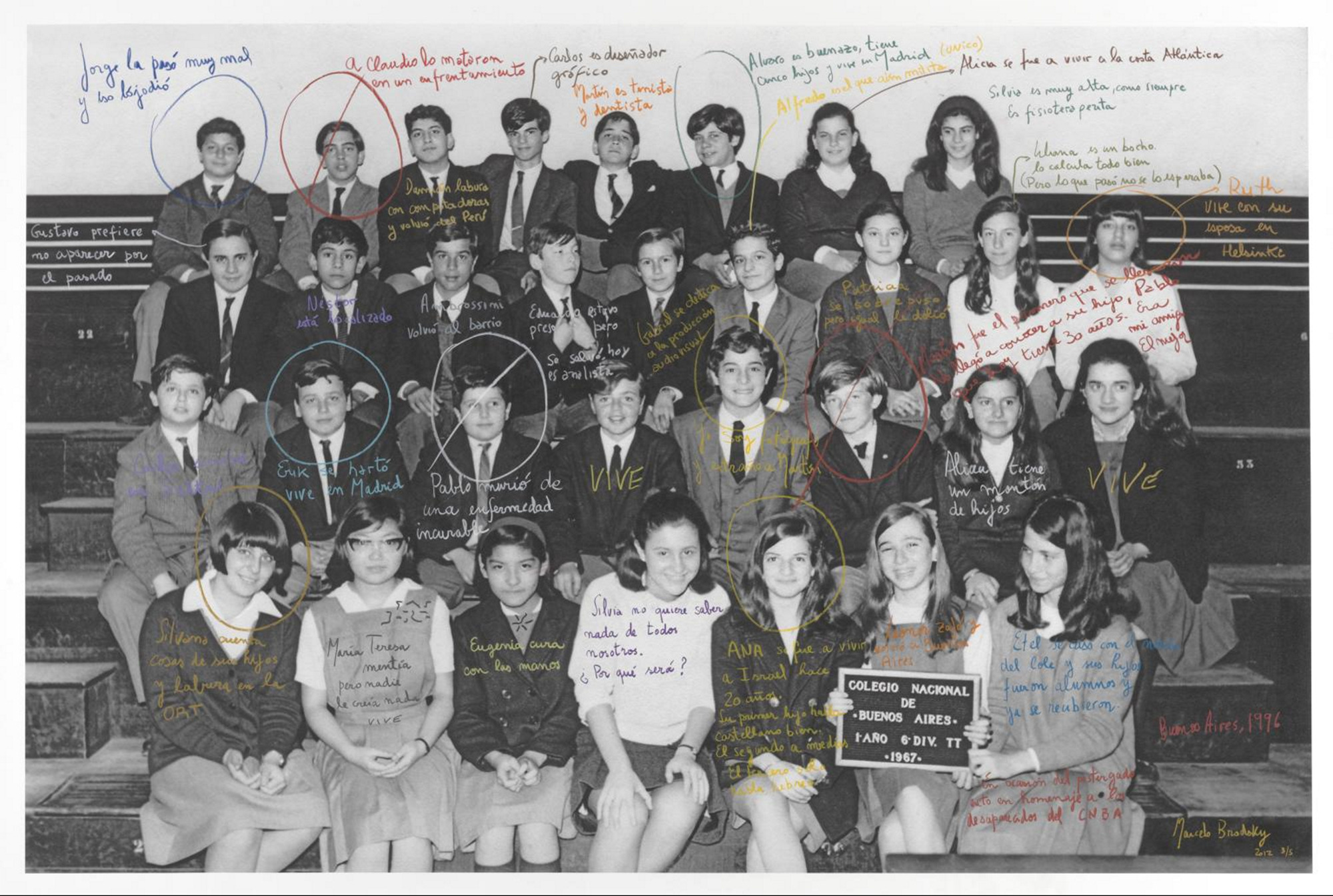

Marcelo Brodsky, La Clase (The Class). 1997. (Courtesy of the artist)

Tom Parker, “Mrs. Ziegler oversees her 9th grade class at the internment camp in Jerome Arkansas.” 1942. Central Photographic File of the US War Relocation Authority, National Archives at College Park Maryland

And yet, despite this official function and usage, school photos also highlight community, solidarity, hope and a desire for learning together with others.

In moments of crisis, such as the one in which we find ourselves in a global pandemic, the togetherness of school, made tangible and real in a group photo, appears all the more precious and all the more fragile. If schools are eager to reopen right now, it is surely in part to recover a sense of community, however inherently fraught, and however impaired by stringent requirements for social distancing.

In our work on school photos, we discuss archival images of multi-ethnically integrated classrooms within Europe and segregated schools in European colonies and in North America that all shared a common purpose: to induce students to conform and become supporters, if not agents, of the ruling state. We illustrate the fragility of the assimilationist project by way of class photos of Armenian children before the 1915 genocide, of Jewish children before and during the Holocaust, and of Japanese-American children incarcerated in concentration camps during World War Two.

In our book and exhibit, the work of artists as diverse as Christian Boltanski (France), Vik Muniz (Brazil/U.S), Tomoko Sawada (Japan), Marcelo Brodsky and Mirta Kupferminc (Argentina), Carrie Mae Weems, David Wojnarowicz, Lorie Novak and Stephen Deo (U.S.) and others, reveal the power of institutions to frame children, and also disrupt and dislodge that powerful institutional gaze through what art historian, and curator, Gabrielle Moser has called a “disobedient gaze”. They invite us to look at these images even while questioning the stories they tell and how they tell them.

Class in American History from the Hampton Album. Platinum print by Frances B. Johnston [1864–1952]. (Gift of Lincoln Kirstein. © The Museum of Modern Art. Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY)

For example, we spend quite a bit of time on photographs from boarding schools created as transformative institutions for Native American children after the American Indian wars, and for African American children after the abolition of slavery. These schools used noted photographers like Nicholas Choate and Frances Benjamin Johnston to promote the assimilationism that eradicated native cultures. So-called “Before-and-After” images deliberately staged the effects of the schools’ conversionist practices. But we also want to show responses to these coercive practices. Snapshots taken by an indigenous student, Beverley Brown at St Michael’s School in Northwest Canada in the 1930’s provide a different student-centered view, as does the work of the Native American artist Stephen Deo, entitled “When We Become our Role Models.” And Carrie Mae Weems’ majestic Hampton Project responds directly to the boarding school images. While Frances Benjamin Johnston pictures the black and Native students in static timeless tableaux, Weems prints these on diaphanous muslin banners, thus unfixing them and thereby undoing the inevitability of the cultural genocide that these boarding schools represented.

The book and the exhibit build on such dialogues between archival images and the work of contemporary photo-based artists.

Installation view: School Photos and Their Afterlives, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. Photo: Brian Wagner.

4. Do you think the concept of memory and time can be applied universally? Do you feel we all remember, and retrace our pasts in the same way? What for you is the biggest counter to the reading of/from memories with respect to the discourse of emergent image cultures?

This is a great question. Of course, different cultures and belief systems espouse different conceptions of time. I came to see how different conceptions of time can be in a number of collaborative transnational projects, especially the transnational feminist collective “Women Mobilizing Memory” sponsored by Columbia’s Center for the Study of Social Difference. Our co-edited book came out last year and includes theoretical analyses of memory as well as art projects, with contributions from Turkey, Chile, Argentina, Germany, the United States and more.

Women Mobilizing Memory. Edited by Ayşe Gül Altınay, María José Contreras, Marianne Hirsch, Jean Howard, Banu Karaca, and Alisa Solomon. (Columbia University Press, 2019)

To return to the boarding schools, for example, one of their missions was to educate native children into what is called “colonial time.” Photographs from those schools often include clocks, musical instruction that reinforces regular beats, all of which contribute to this form of assimilation.

The idea and the work of memory certainly complicates and challenges the notion of linear time and progress that has dominated Western world views since the Enlightenment. Scholars of memory suggest that memory is in the present—that memory and the past shift and change in relation to shifting presents. Scholars of trauma, however, have shown that traumatic events, especially those that have not been acknowledged or worked through, remain and return, spiralling time in an endless set of repetitions and returns.

Of course, memory also has a future: we invoke the past specifically in the interest of the future we look toward. This is especially evident, I think, in relation to photography. True, we now tend to take pictures endlessly with our phones, not so much so as to look at them later but to respond to our experiences in the present, whether it is to remember them or to shield ourselves from their full impact now. But more formal photographs, especially the institutional photographs I have studied, are taken to be looked at in the future, to measure time.

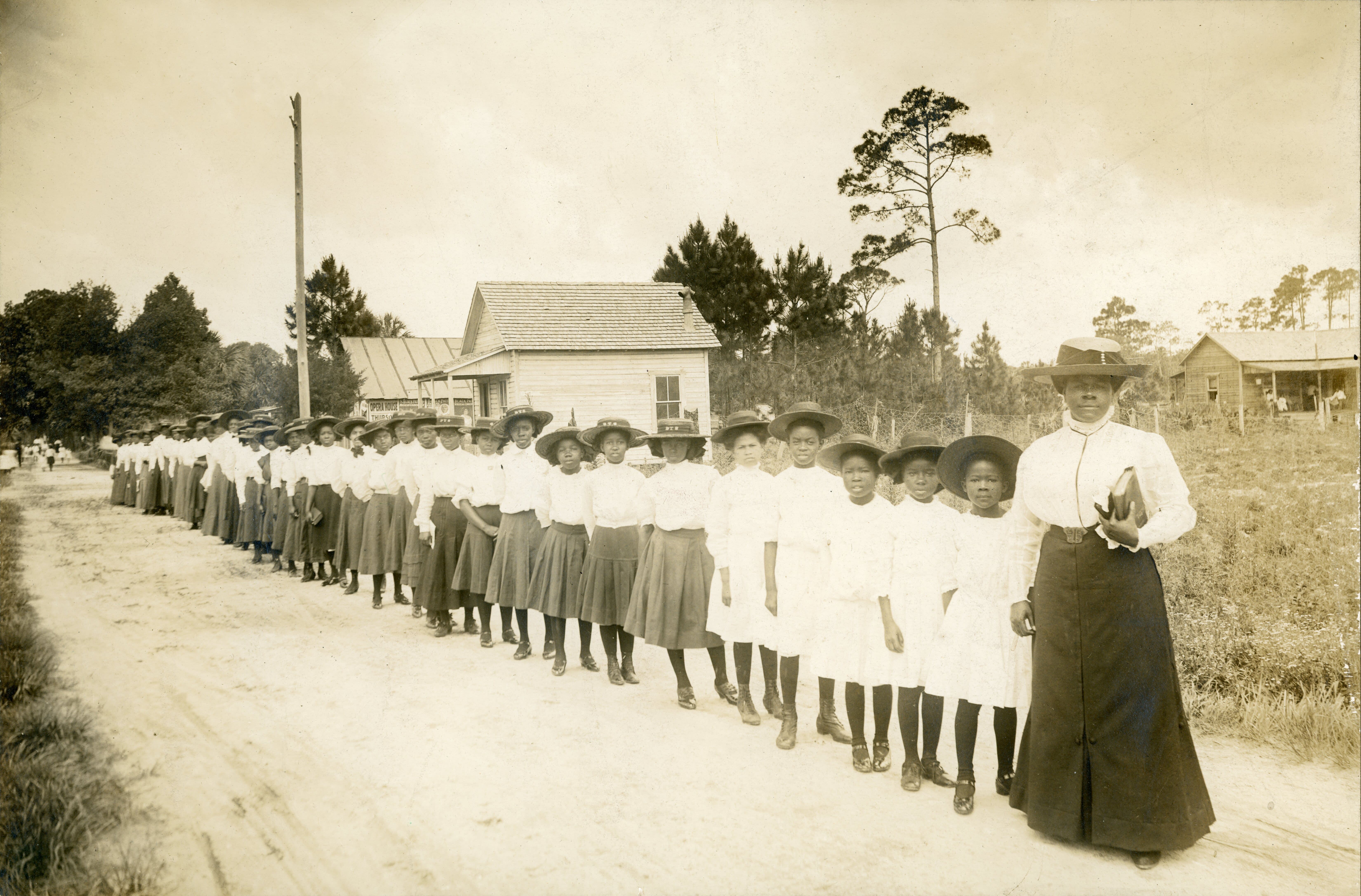

Unidentified photographer, Mary McLeod Bethune with a Line of Girls from the School from the Daytona [Florida] Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls, about 1905. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory; N041432.

The work I have done with images of children, children who are often looking toward a future they would never be allowed to live, has made me wary of the retrospective ways in which we engage with photographs and with memory. What future were the subjects of our inquiry looking toward? Can we grant them their own present and their own future, rather than seeing them through the fate we know was to be theirs?

The echo of water in photography evokes its prehistory. – Jeff Wall

In the book on school photos, we develop the idea of “liquid time,” inspired by sociologist and philosopher, Zygmunt Baumann’s important work on “liquid modernity” and also on a short essay by the artist Jeff Wall, “Photography and Liquid Intelligence.” Photographs, of course, do more than document the time of their production. Wall derives the idea of “liquid intelligence” from the developing process for analog photos.

In a darkroom, both the camera film and the photosensitive paper onto which the image has been projected, are immersed into a liquid solution. Until they are chemically “fixed,” they change and transform, often in unexpected ways. We could say that photographs are never really fixed, but that they keep developing over time. They acquire new meanings as documents of history, and they have new roles to play as objects of memory and as historical actors in the present.

Comments