Both/And: Shezad Dawood

Still from Kalimpong, VR environment, duration variable, 2016, Courtesy: UBIK Productions.

London-based artist Shezad Dawood’s practice straddles film, images, sculpture, sound, virtual reality and various other fields which include science and fantasy. He studied at the Central Saint Martins (1994 – 1997) and the Royal College of Art (1998 – 2000) before completing his PhD at Leeds Metropolitan University (2008). Dawood had a multicultural upbringing – an Indian father, Pakistani mother and an Irish step-mother, and now acknowledges his lineage as a resource for research, leading to intermedia improvisations and cross-disciplinary collaborations through music and dance forms.

Though his work may seem varied in style and content – the appearance of a Yeti for instance – what anchors Dawood’s practice is the centrality of the image, even cyber space, tapping into the edge of an awareness or examining the heightened consciousness of the body through sound. In this conversation, the artist shares how aspects of the transitory, the liminal, the existential and the fractured, give way to a new sense of mutuality and acknowledgement in his practice. Dawood translates this experience into the binary meld of a condition he calls: ‘both/and’.

Veeranganakumari Solanki (VS): You grew up in London – a cosmopolitan, multicultural space. As an artist, you are often expected to address the othering diasporic lens as a focal point. Could you speak about your experiences with this aspect and how you have tackled it?

Shezad Dawood (SD): For me it was an interesting journey, because I’ve grown up and made work in so many locations. I think ‘normalcy’ and ‘otherness’ are weird, inter-related categories that are always in dialogue with one another. I don’t think anybody is normal and we are all othered in some way. The pretence of not accepting this can lead to defensiveness, territorial insecurity and ultimately to the divisive politics of nationalism. For me it’s important to push against that tendency. How do we move outwards? How do we find points of connection, intersection, sympathy, empathy and compassion?

Even during my undergraduate years in London, I was pushed into making work about identity politics and the dynamics of representation and I pushed back by talking about more global issues. I did not want to create a brand identity for the market or be pigeonholed into how I might be seen. Over time, I realised that even pushing back is a reaction that has weight. At the same time, I wanted to step out of a reactive space, and step into a generative space. It became an approach that has become very critical to the ‘both/and’ approach. The ‘both/and’ framework allows me to challenge myself continually and disrupt a recognisable pattern in my work. Ever so often I hit a brick wall, where people don’t understand the work or the interconnectedness of two works. I’ve learnt from these experiences to pick myself up and go somewhere where there is an understanding and a willingness to work discursively.

VS: How did textile enter your practice – from South Asia, Africa and East Europe for instance – and how does it weave in a personal narrative?

SD: I come from a family of several generations of textile merchants. However, I went off to art school rather than what was seen as a more valued profession. Though this was initially quite disappointing, it’s quite interesting that textile became a major part of my practice. For a number of years I worked with textiles from South Asia because I was familiar with them, but I grew outward from there. My studio, often overflowing with textiles, wasn’t that different from my grandfather’s shop on Marine Drive in Mumbai, decades ago. I ended up coming full circle! I had been collecting textiles, particularly Ralis and Kanthas for years without knowing what I was going to do with them. Sometimes, not knowing ‘what’ or ‘why’ you are doing something is a nice instigator for life in general. It was at my show, Kalimpong in 2016 (Timothy Taylor, London) that I first introduced raw canvas and textiles from other places such as Nepal, East Asia, Africa, and Romania.

For me, textiles have always been polyglot. They encompass trade routes, conversations and a sort of mongrel hybridisation which felt very true, even to how I see myself. It’s funny how a lot of terms such as ‘hybridisation’ have been used in a way to exercise power. As we know that language too is a form of power, power for me is extendedly a form of magic. How do you reverse an existing syntax? A major influence on me, when I was studying, was the work of political scientist and feminist, Françoise Vergés and her ideas on métissage or mixed heritage. That, in the space between power, nation and identity is the space of the generative, the space of the other that exists beyond the borders of the known, and I’m sure as artists, that’s what we are always striving for.

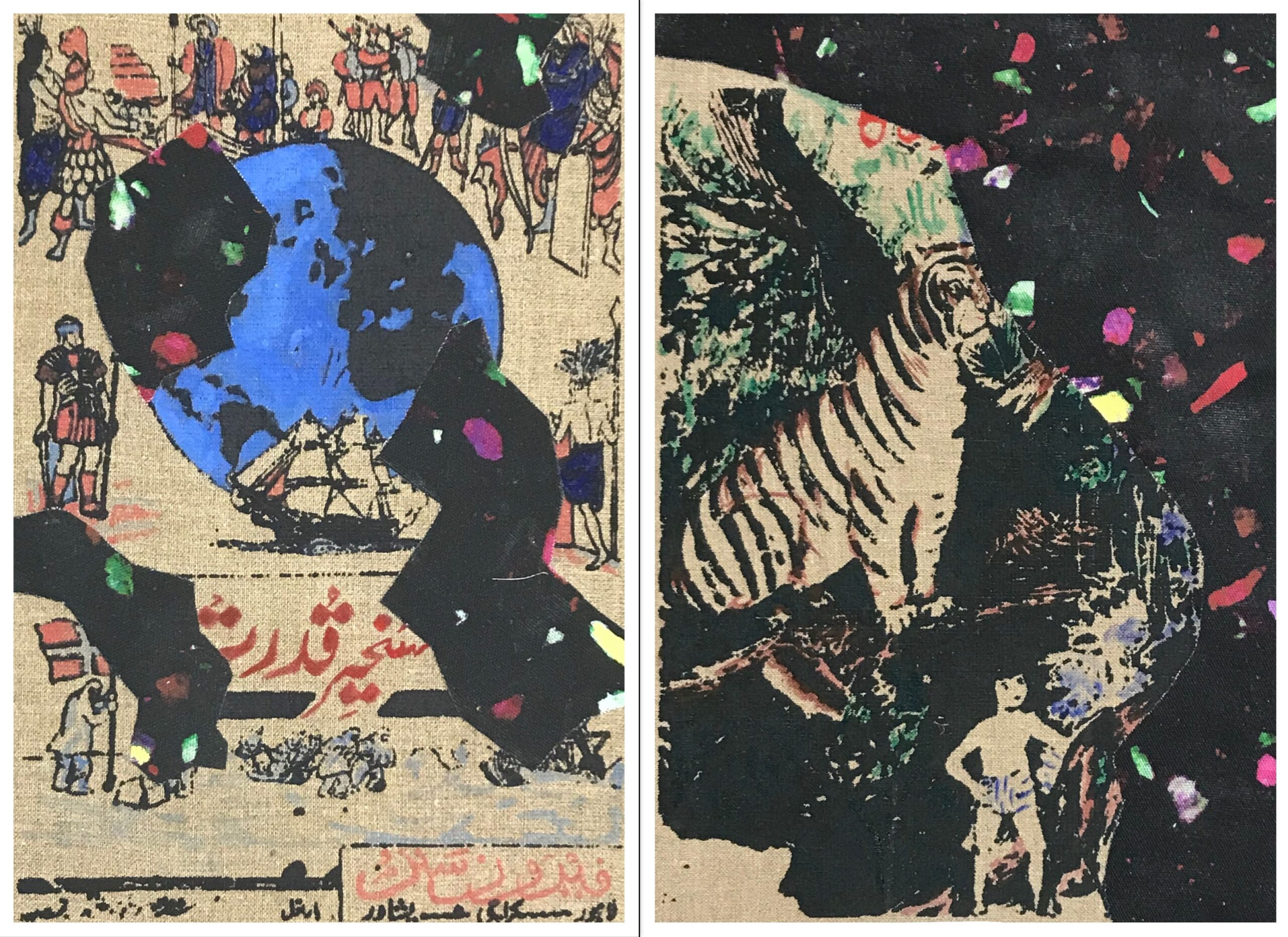

Left: Colonial Adventures I, Oil, acrylic and textile collage on canvas, 32 x 21 cm, 2020. Courtesy: Jhaveri Contemporary.

Right: Colonial Adventures II, Oil, acrylic and textile collage on canvas, 32 x 21 cm, 2020. Courtesy: Jhaveri Contemporary.

VS: In some of your works, such as the Golden Jubilee Naan (2002) or more recently, Colonial Adventures: I and II(2020) there are direct references to this hybridisation of history revealed through the fraught relationship of the coloniser and the colonised. Could you talk about how you have also let subtle humour slide in there?

SD: I supposed it’s making gestures that are both ‘throw away’ and meaningful simultaneously. It’s about how work can operate on those registers in parallel. I’ve always believed that a certain amount of humour and playfulness can draw people into the work for a more considered reflection. I don’t like power and the way it seeks to operate and dictate experience. It’s been quite important for me that work should operate ethically and, on several layers, simultaneously, so you are not excluding anyone, and that is, I suppose, the necessary generosity of being an artist.

VS: That leads me to think about the element of mystery and the unknown that has such a strong presence in your work. There are so many references you make to mythic space, extra-terrestrial life and outer space. The lay of the land seems something fathomable in most places, yet, there is this sense of exploration and discovery layered with science fiction. Could you speak about where these elements come in from and why they hold such a central position in your work?

SD: There are two ways I could answer that. The first builds on what we are already discussing, about how something keeps expanding out from a closer reference base and moves outward with this idea of otherness and hybridity, such as in Colonial Adventures I & II(2020). The works are re-drawn from the titles of two of my favourite book cover designs and my reinterpretation of their graphic illustrations. The first is Sundar Quadrat or Admirable Abilities which is about the history of the world – on everything from the Roman Empire to the American Empire. It becomes a way to think about power through time, using the title to construct a playful inversion of meaning. Colonial Adventures II is from a beautiful Urdu edition of the Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling. Kipling was a propagandist of Empire, but there are older generations in Britain who are fiercely defensive of Kipling and his legacy. So, it’s interesting how there is an inability to critically reflect on the function of something with a nationalist agenda. How does one move from that?

The second response is to that space of the ‘unknown’. With reference to Vergés’ question of the ephemeral space between fixed identities and meanings, I’m thinking about the sea, that becomes the vast unknown, and yet, is the vector through which colonisation or Empire takes place. The sea is the grandest allegory because we are always thinking of the surface of the sea in a very sort of human hubris of flat expanse, yet there are fathoms beneath this! And this for me links back again to questioning the function of the artist. It is to step into those spaces that are uncomfortable, to resist forming a constricted identity and allow for opportunities to open up. It is to keep looking.

How do we go together into a space and ask questions? For me that’s all that life is really about. It may be about trying to hold on to a childlike fascination of the world, but that is the source of all joy. I want my work to be a shared experience, where I’m not telling my audience what to think. I want to pose questions together that are both challenging and joyful, and that for me, is an evolutionary vector.

Kalimpong, VR environment, duration variable, 2016. Courtesy: UBIK Productions.

VS: There is also a dominant presence of mostly unrecognisable living forms – from underwater sea creatures, to neon monsters and mythic beings such as the Yeti in Kalimpong (2016) and similar such encounters in your other VR works. You make the environment/ space immersive, where one enters, experiences and exits the work in a seamless transition. Could you speak about using Virtual Reality as a medium and the way you explore the unknown through it?

SD: For me, the idea of thresholds is very important especially when considering the audience’s generosity of time with my work. When someone steps off the street into an exhibition space or a site-specific project, what does that transition and transaction feel like? The audience is conferring on me an act of generosity by stepping into my universe, and so what am I offering in return? That is what the threshold holds, a gift of the artist’s labour in return for the gift of the viewer’s attention. This implicates the entire exhibition design, including the spaces between works. That is the beginning of creating something immersive, whether it’s film or VR.

I discovered VR by accident through a friend, Scott, who has always challenged and pushed me to think outside of the box. While talking to him about immersion in experimental films, he said I needed to look at VR and got me an HTC Vive to experiment with, a few years before it was available in the market. This additional time allowed me to incubate possibilities and really think about what I was trying to do. Kalimpong was the perfect vehicle for my first VR work because of the very nature of the space it was investigating and inhabiting. I could pose questions about real and perceived boundaries, the exoteric and the esoteric, history and fiction and all this was successful only because I had time, and time in itself holds a sense of generosity that disrupts logic.

The aspect of the ‘unknown’ is a projection of our fears and insecurities, whether it’s through a 1950’s American fear of the Soviet other or a fear of racial others in many national frameworks. So, the Yeti or the neon invasions for instance, play on a cold war politics in Pakistan and the neighbouring Afghan theatre, or a proxy war between the CIA and the Soviets. I’m interested in this interconnectedness – that nothing is as black and white as we would like it to be for the sake of convenience, and that questions must be posed in the critical space between history and fiction. We know this as descendants of subjects of Empire, as immigrant children, there’s an interesting idea of displacement, but that displacement is everywhere. It comes through wealth inequality, a lack of educational equivalence. I think we are riven with it within human societies and it’s really important to take it to task.

VS: In addition to history, cinema and the image have been quite central to your work. Could you speak about the use of textile and image in your work and how they all converge into your discourse?

SD: Image culture has accelerated and dominates our perceptual field. As much as we think about it as a contemporary phenomenon, image culture existed even before Gutenberg invented the printing press. The propaganda wars between the Florentines and the Ottomans were based on image and perspective. I can’t stop myself from thinking about the parallels between the image, cinema history, ideas of time –both experienced and philosophical. Who decided that motion would be 24 frames per second? Sometimes it’s 25, depending on which formats you are working with. I love playfully accentuating these things. Making a film work on the one hand, but then making a contrasting work on a piece of fabric that talks about cinema is something that 24 Frames per Second (2016) does. It’s not moving, yet, it is, because there are ideas and thought patterns moving through it. Multiple White Out Palms (2017), a rug work, is based on a loom with the idea of a loom etching cinema in its warp and weft. It’s about the construction of time as both a mythic and human jurisdiction.

Installation view of Joe Versus the Volcano, Avebury Rock and Multiple White-Out Palms, woven by Brintons, 2017. Collaboration between Brintons, General Projects and Clerkenwell Design Week, 2017. Photography: Oliver Rudkin

VS: Could you speak about the presence of sound and music as an intersection of your work and what collaborations mean for you in your practice? Particularly with reference to Passages (2014) that you made with Steve Beresford, there are layers present of a deeply collaborative process.

SD: I have always worked to disrupt patterns. For this, collaboration has been a mainstay in my working process. The conversations challenge me and undermine my role to create a sole framework that becomes so important and rich with the amount it includes in the form of content and further thoughts. I should confess though, despite my great love and also knowledge of different music and musical histories, I’m a lousy musician myself, so there’s a pragmatic aspect to collaboration when it comes to sound!

I’m quite interested in the synesthetic, and perceptual slippage between one medium and another, so when I’m thinking through a film, it’s achieved sonically, through a sound palette before the image palette or the script. Frequencies and a non-linear approach, derived from the history of experimental films are key elements when I edit but at the same time, I’m very interested in narrative. So again, it’s a both/and situation. Where does the work pull you into a narrative trajectory and then throw you out again as it becomes more of a collaged metaphorical symbiosis of sound and image and then where does it pull you back into narrative? And those peaks and troughs are a different way of pulling people through a film – a purely narrative or purely experimental kind of vector.

I had a solo show at Parasol Unit in 2014, when Op50 (a London based arts organisation dedicated to Artists’ Audio) who did interesting collaborative vinyls between artists and musicians asked me to do something. Passages was the outcome of this. It was a collaboration I had been wanting to do with Steve for many years about translation and influence. The work became this bizarre journey between Edgar Allan Poe’s poems and Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending A Staircase and the composer Olivier Messiaen’s chromatic scales that were meant to make one see colour based on musical notation. I asked Steve to free-improvise using Messiaen’s scales while looking at an image of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase that resonates with the idea of moving up and down the scale. This was installed with discreet speakers on the stairwell at Parasol Unit, where I watched people’s rhythm of walking become assonant and dissonant as the scales came in and out. Ditto in London collaborated for the sleeve design and I used a digital render (part of my creation process) of my sculpture that was also on display at Parasol Unit, as the cover image.

So, again this idea of the space around and between things is so vital to being conscious of things around us. How we connect and how present we are. To move forward we need to ask questions, think about how we work together, particularly at this moment where it seems more fragmented and divided than ever. I think it becomes all the more important, for those of us who can, to hold the light and have the courage to look outward and safeguard that light for the future.

Shezad Dawood and Steve Beresford, Passages, 2014, collaboration for Op50 (Lp Album, Edition of 200)

Shezad Dawood, Artist portrait image by Alexander Coggin

Shezad Dawood was born in London in 1974 and trained at Central St Martin’s and the Royal College of Art before completing his PhD at Leeds Metropolitan University. Dawood is a Senior Research Fellow in Experimental Media at the University of Westminster. He lives and works in London.

Comments