Collecting family photographs

Installation view of The Family Camera exhibition (2017). Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM. Photo Credit: Brian Boyle, MPA, FPPO.

“I am a passionate lover of the snapshot because of all photographic images it comes closest to the truth.”—Lisette Model (Zuromkis, 2013, p. 159)

Launched in 2016, The Family Camera Network induced the generation of family archives at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM hereafter) in Toronto. The museum set about collecting, preserving and later exhibiting photographs of Canadian families, many of which are from South Asia, in order to engage with the changing idea of lineage, ancestry and even generational divide. The initiative aimed to prevent such memorabilia from being decoupled from their histories; or being ‘orphaned’ when the families had immigrated to a new country.

From a historical trajectory, the presence of personal photography at the ROM, presented as loose images, albums and even snapshot cameras, foregrounds some important mandates about institutional directives today with regard to acquisition and presentation. At a time when the modernist aesthetic of the museum continues to dominate in some measure—isolating images as ‘art’ objects, showcased in the museum where they rise to an elevated position with an autonomous aesthetic (ibid, p. 121)—invokes a broader investigation: what kind of photography can eventually become part of or displayed in museums as repositories of knowledge, tradition and eventually community?

Initiatives such as these highlight the critical need to salvage the so-called ‘(non)aesthetic’ of snapshot photography in order to move into and beyond what is being witnessed in images, and further excavate background information in the form of oral family histories for instance—intimate stories which move from the private space to the public realm. With exhibitions like The Family Camera, the ROM now creates an active public archive, which is testimony to stories of migration, displacement and resettlement that help investigate vital questions around the idea of our origins and identity.

Historically too, exhibitions round the world have also tried to engage with certain universal notions surrounding ‘society’ and the ‘everyday’ through more pictorial photography, such as the Family of Man in the 1950’s (which was exhibited in Mumbai in the mid-1950s); or even Close to Home, in more recent times which explored the idea of national identity through images created around the world. There are other contemporary references in India too such as images of Goan diaspora in an exhibition curated by Prashant Panjiar titled Old Homes, New Homelands; and investigative, local initiatives such as Bodyguard Lane in Mumbai by the BIND Collective.

As we ponder these developments, some questions come to mind: What comprises a family photograph? Is the notion of a family universal? Have technological advancements endangered their existence as objects that need preservation?

Here, Deepali Dewan, Curator of South Asian Art & Culture at the ROM, and one of the seven-member collaborative curatorial team of The Family Camera (6 May – 29 October 2017), shares her point of view about the Family Camera Network as well as the exhibition and talks held in September 2017.

How did the initiative to acquire family photography begin at the Royal Ontario Museum? What was its main purpose?

The initiative to acquire family photographs at the ROM is part of a larger project called “The Family Camera Network,” which also collects material at the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archive in Toronto (www.familycameranetwork.org). Thus there are two collecting institutions in this project. My motivation to start the project at ROM came from an observation that current photo histories predominantly focus on known photographers and iconic photographs of known origins and dates. They usually fit into established categories of documentary, portrait, landscape, fine art, etc. While “vernacular” photography has received some robust attention in recent years, this structure still leaves out many categories of photo practice.

One of the biggest absences, it seems to me, is family photography. Indeed, it seems like a contradiction that a genre that is the most familiar, numerous, and ubiquitous was also the most absent from photo history. In my research on the history of photography from the South Asian region, I have felt unsatisfied that I couldn’t write about family photography as part of a larger history of photography because there had been so little scholarly work done. And there had been little work done, it seemed to me, in part because of the lack of institutional collections where scholars could go to look at such material. In cases where there were collections, it was either “orphaned” material (where the details about the families and circumstances depicted had been lost), or elite material that documented the genealogy of upper-class families, or material reflective of local communities – but little information about the photograph itself. In no instance was there a collection of family photographs that preserved their histories along with the images in such a way that revealed how the photographs themselves were produced and used and what meaning they had for the people who produced and consumed them. That is, no collection preserved the practice of family photography.

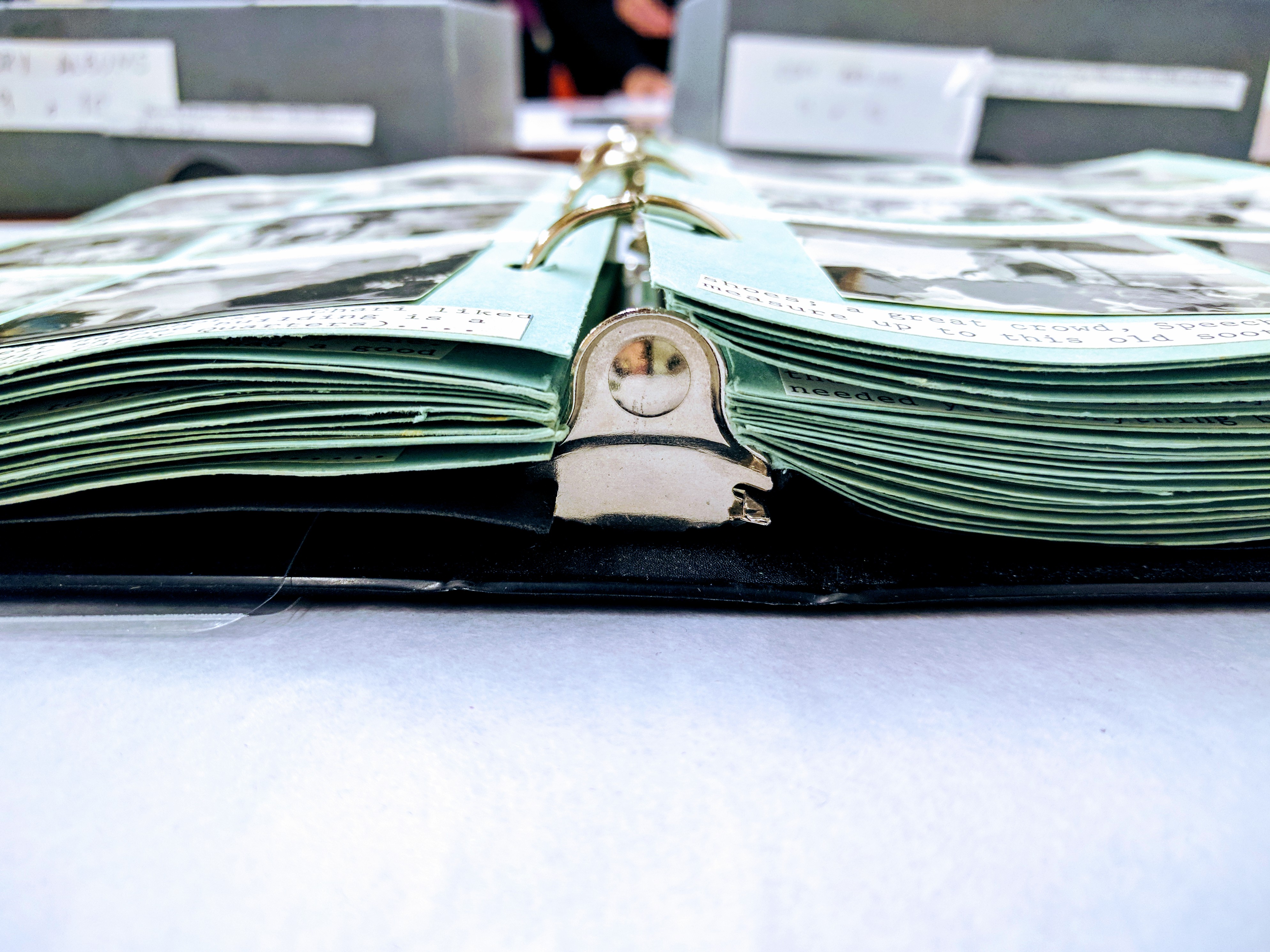

Albums collected through The Family Camera Network at the ROM. Gift of Beverley Martin. Courtesy The Family Camera Network. Photo Credit: J. Orpana, 2016.

Albums collected through The Family Camera Network at the ROM. Gift of Beverley Martin. Courtesy The Family Camera Network. Photo Credit: J. Orpana, 2016.

Indeed, it seems like a contradiction that a genre that is the most familiar, numerous, and ubiquitous was also the most absent from photo history.

Having the privilege of working in a museum whose purpose is to collect and preserve aspects of visual culture for future generations, I felt there was an opportunity to create the kind of archive I was craving to use myself. And, as a public institution, ROM could make it accessible to researchers, scholars, and a general public. An important aspect of this collecting project is that the material is collected directly from families, before photographs end up in the market place or in circulation beyond the family because someone had passed away or that the family no longer had a connection to the people in the images. These oral histories are preserved as video interviews in which the families talk about their photos, including who is and is not in the photo, the circumstances and family dynamics that are visible and invisible, what photos held meaning and how they were used in the home.

While embarking on this project, many issues and questions have come to light during the process that are worth noting. For example, the notion of “family” is not universal but rather an evolving social and ideological category. For this project, family is understood broadly as biological, adoptive, or chosen, in the sense adopted by LGBTQ+ communities. We also found that ‘family photography’ required some definition. For the purposes of the project, we found that it was important to be expansive in what constitutes family photography, as a range of material that may occupy a domestic space and intersect with public spheres. While mostly produced by amateur photographers, it could also include studio photography displayed within the home, or even non-photographic material that comes to stand in for family members when photographs were not available.

An important aspect of this collecting project is that the material is collected directly from families, before photographs end up in the market place or in circulation beyond the family because someone had passed away or that the family no longer had a connection to the people in the images.

Further, the absence of family photos from photo history is not a new observation. Indeed, one could say there has been a “family photo turn” in the field and more photo historians have started to write about family photos. And yet, the lack of collections in institutional archives is palpable. Most photo historians have turned to their own photo collections to be able to write this material into the history in a robust way because they know more about who is in the photo, what is going on, when it was taken, and how the photos were used or not used. The Family Camera Network archive at the ROM and the CLGA are meant to preserve the cultural practice of family photography—images and their stories—to write more robust histories of photography.

Albums collected through The Family Camera Network at the ROM. Gift of Beverley Martin. Courtesy The Family Camera Network. Photo Credit: J. Orpana, 2017.

Albums collected through The Family Camera Network at the ROM. Gift of Beverley Martin. Courtesy The Family Camera Network. Photo Credit: J. Orpana, 2017.

How are the diasporic communities, especially from the South Asian region being referenced and archived by the museum?

The project focuses on family photos that reflect experiences of migration. Migration here is understood broadly as any form of movement, transnational or within a nation. It takes into consideration that movement from a rural to urban setting can be an impactful experience – as is crossing an ocean. Migration is also understood as having happened in the recent past or generations ago, both having a profound impact on families. As a result, many families that have shown interest in participating, have been from various diasporic communities. In part because of my role as curator of South Asian art and culture at the ROM, there have been numerous families of South Asian descent who have shown interest in participating.

Installation view of The Family Camera exhibition (2017). Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM. Photo Credit: Brian Boyle, MPA, FPPO.

Installation view of The Family Camera exhibition (2017). Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM. Photo Credit: Brian Boyle, MPA, FPPO.

The history of the South Asian diaspora in Canada goes back to the late 19th century when many people from Punjab came to the west coast and worked in lumber mills. These migrations were not straightforward nor without hardship. Since then, there have been successive waves of migration from South Asia, each marking a different intersection of Canadian and South Asian history. At present, families with roots in India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka have participated, as well as some who first migrated to East Africa and the Caribbean. That said, the project from its inception has not claimed it represents the diasporic experience in general or that it includes representatives from all diasporic communities. In this way, the project tries to resist what one can call a ‘colonial-period organizational strategy’ that claims universality for the particular. Rather, the archive of family photos collected at the ROM is representative of nothing but the families who have shown an interest to participate.

The stories that are emerging from the project show us that families from diasporic communities can have varying connections to the places from which they migrated, some returning frequently and others with little contact. They tell us that the sharing and circulation of family photographs plays a huge role in mediating the connection between families now separated by geographic distance. In some cases, there are moments of disconnect as people look at images of ghostly faces staring out from the past, which represent people about whom the current generation knows little. In other cases, it is precious family heirlooms that are the only connection to the old country and family back home. And in others still, family photos become the things through which connections are maintained and negotiated, through the sending of photos through the mail or carried by friends and family members who travel back and forth. The notes hand-written on the back of images identify events and people and dates, and can even share stories or emotions, creating familial intimacies across distances. In this way, the hand-writing mirrors the indexical trace manifest in the photographic image on the other side.

The project even collects born-digital images to preserve the new ways images are created and circulate through the internet, especially social media platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp, making new connections between disparate family members that would not be there otherwise.

What was the curatorial slant of the recently held exhibition, The Family Camera?

From the archive of family photographs collected at the Royal Ontario Museum, we organized and mounted an exhibition “The Family Camera” that was on view from May 6 to October 29, 2017. There was a curatorial team who put it together, including myself, Jennifer Orpana, Thy Phu, Julie Crooks, Sarah Bassnett, Silvia Forni, and Sarah Parsons. The exhibition explored how family photographs play a role in reflecting and shaping experiences of migration. The curatorial contention was that family photos did not simply document or reflect the past nor play a nostalgic role within the family setting but rather serve as a productive agent in shaping how one thinks about family, about community, and indeed about oneself.

The exhibit resisted the assumption that family photos are universal, instead highlighting moments when family photos are absent (destroyed or abandoned) or simply never taken (due to state intervention, poverty, or simply not the cultural practice of choice).

The exhibit self-consciously included material from marginalised communities to question the normative visions of family. For example, the majority of participating families were from communities of colour from the global south. It also included photos and stories from LGBTQ+ communities whose notions of family often must contend with those defined and regulated by the state. Importantly, the exhibition also acknowledged the experiences of indigenous families in relation to the traumatic impact of the residential school system, which tore families apart. The exhibit resisted the assumption that family photos are universal, instead highlighting moments when family photos are absent (destroyed or abandoned) or simply never taken (due to state intervention, poverty, or simply not the cultural practice of choice). In this way, the exhibition was an attempt to explore family photographs in ways that were familiar but also surprising for visitors. It centred the experience of marginalized communities but in a way that it became woven into the narrative of the exhibition. Given that “The Family Camera” opened for 6 months during Canada’s sesquicentennial celebration, we hoped that its overall message, of the visual mediation of migration, provided a richer picture of the fullness and complexity of the nation’s transnational linkages.

Installation view of The Family Camera exhibition (2017). Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM. Photo Credit: Brian Boyle, MPA, FPPO.

Installation view of The Family Camera exhibition (2017). Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM. Photo Credit: Brian Boyle, MPA, FPPO.

The curatorial contention was that family photos did not simply document or reflect the past nor play a nostalgic role within the family setting but rather serve as a productive agent in shaping how one thinks about family, about community, and indeed about oneself.

What do you hope to achieve in gathering such material in the future? What are some of your forthcoming activities?

This project is part of a larger research project called The Family Camera Network. It has been a 3-year project funded by a Partnership Development Grant from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (we are currently in year 3) that involves 6 partner institutions and over two-dozen researchers in Canada and the United States. Dr. Thy Phu of Western University is the Principal Investigator. This project is an exploration of family photography through the theme of migration. Creating an archive of family photographs is one of the components of the project. Thus far, we have videotaped over 30 oral histories and collected over 10,000 photographs. We have also organized an international conference, a symposium, conducted workshops, given lectures, served on panels, curated public art installations, and inspired a documentary. In the future, there will be more exhibitions in Toronto featuring different aspects of the archive.

Working in collaboration with our participants, we hope to put as much of the archive as possible online so that it can be widely accessed and searchable. After the conclusion of this research grant, we will explore what may be future manifestations of the project. One direction that is being explored is to think about what a global consideration of family photographs would look like, through collaboration with several international partners. Read more about the project at www.familycameranetwork.org.

Interview by Rahaab Allana

Deepali Dewan is the Dan Mishra Curator of South Asian Art and Culture at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. She is also an Associate Professor in the Department of Art at the University of Toronto and is affiliated with the Centre for South Asian Studies. She is also part of the Toronto Photography Seminar, a group of scholars from Ontario institutions who read, produce, and edit collaborative research concerning the history and theory of photography. Her research spans issues of colonial, modern and contemporary visual culture, knowledge production, and historiography.

Comments