New Terrain: In Conversation with Beth Citron

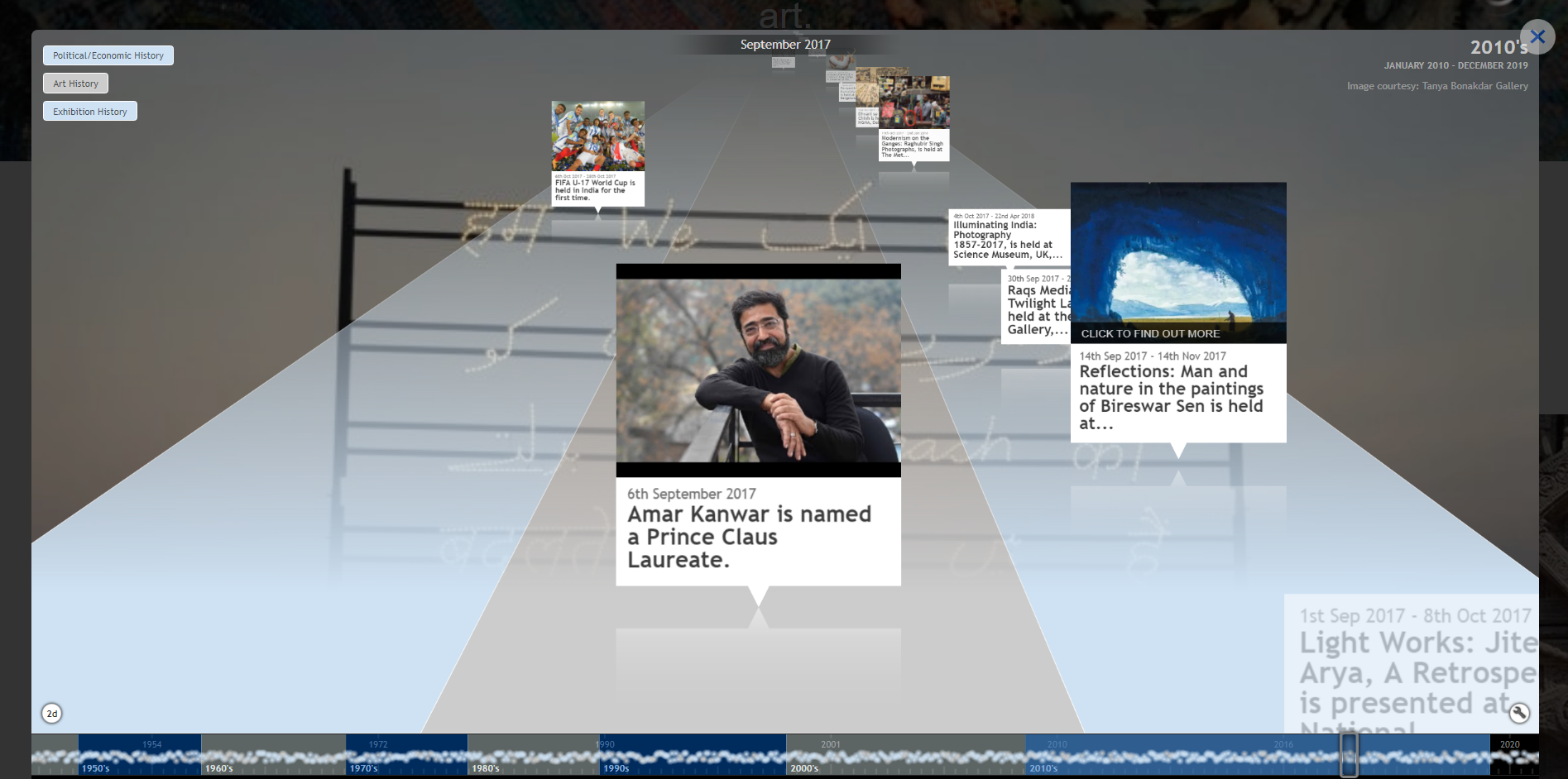

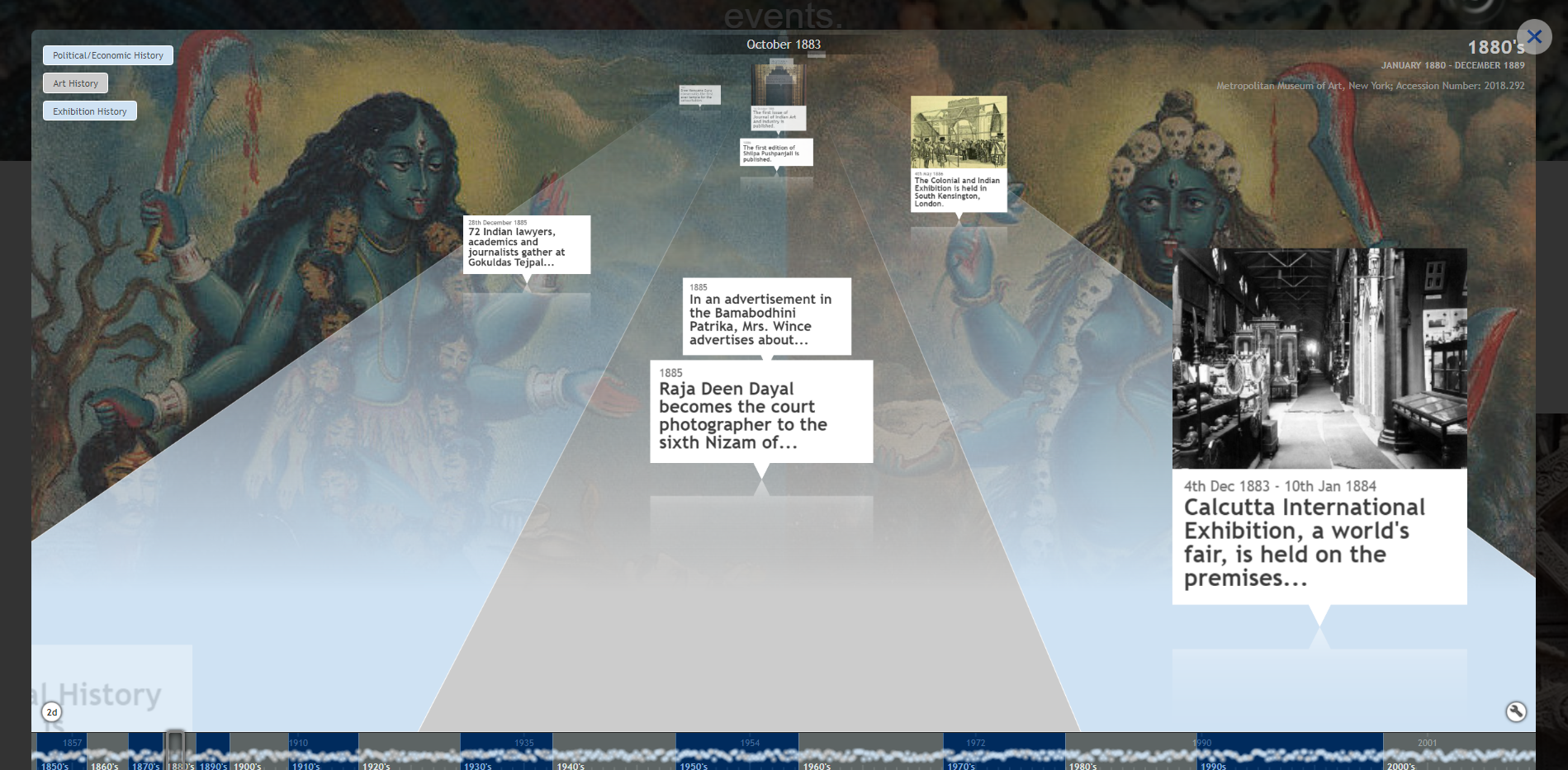

Screenshots from the art history timeline feature on Terrain.art

Beth Citron is a curator and scholar who has worked extensively in the South Asian region. She is the Artistic Director for the newly launched blockchain powered digital platform terrain.art (currently in soft launch) and former Curator for Modern and Contemporary Art at the Rubin Museum, New York. In this interview with Rahaab Allana, she shares insights about the making of a blockchain platform for art, the challenges behind digital archival work and its potential for pushing the discursive boundaries for archives at large.

Installation View from the exhibition Allegory and Illusion : Early Portrait Photography from South Asia at the Rubin Museum, October 2013 – February 2014. Curated by Beth Citron and Rahaab Allana.

RA: Education and awareness enhancement was very much part of your mandate at the Rubin Museum. But you’re now moving from curating live exhibitions to virtual dissemination. How has that shift been for you?

BC: Aparajta Jain approached me about what became Terrain in January of 2020 – pre-Covid – with this idea of a blockchain powered virtual platform and at the time it seemed really cutting edge and revolutionary. Who knew that our lives were about to go completely online?

One of the aspects that I liked about my previous role was the ‘startup’ quality of the Rubin Museum . I joined essentially in its infancy and worked to build up a modern and contemporary art and photography program that could sustain itself over the long haul. While this program was focused on South Asia, the Rubin Museum has gone back now to its core mission of Himalayan art. So I think over nine years there, we were able to build a program that was discursive and contingent, where exhibitions and associated public programs weren’t just one-off initiatives, but scaffolded.

Screenshots from the art history timeline feature on Terrain.art

The thought that we originally had about Terrain, on the other hand, was that a virtual space is nearly unlimited – the potential for growth is immense. Now we’ve been living online for the past year, and the proliferation of online platforms and outlets was unanticipated. The opportunity that I see is truly in the blockchain component, the opportunity to create digital catalogue raisonnés for artists and have India leapfrog past the kinds of digital archives that have become common globally. It requires some faith and trust that isn’t fully there yet because it is a new technology, a new way of working and requires a shift in mindset. It’s important for the Indian art world and eventually for Indian art history. Originally, my own thinking about this was more limited: what we were going to do was stop the dissemination of fakes. Now I feel that the potential around this project is actually much greater in terms of empowering artists to be able to keep track of their works over the course of their careers, and possibly with some policy changes even benefit from resale rights, as in France. Eventually, these archives will also be instrumental for research and writing art histories around authenticated artworks.

RA: As you are going about the work of building scholarship around India for terrain.art , do you see this as a space that is going to be accessible to a larger demography?

BC: With Terrain, one of the first projects that we did in terms of educational resources is a series of 20 short videos explaining foundational art and art history terms, including photography, performance, portraiture etc. At first we started out thinking that they would all be under a minute so they could live on Instagram and a lot of resources went into this. You go from making these big exhibitions, sometimes with catalogs, to figuring out how you can explain all of photography in a minute… and you can’t. But accessibility meant reaching more people with these short-format introductions, with a commitment to engage in content with zero jargon and therefore helping people to want to learn more. So it’s a scaffolded approach to education in that sense.

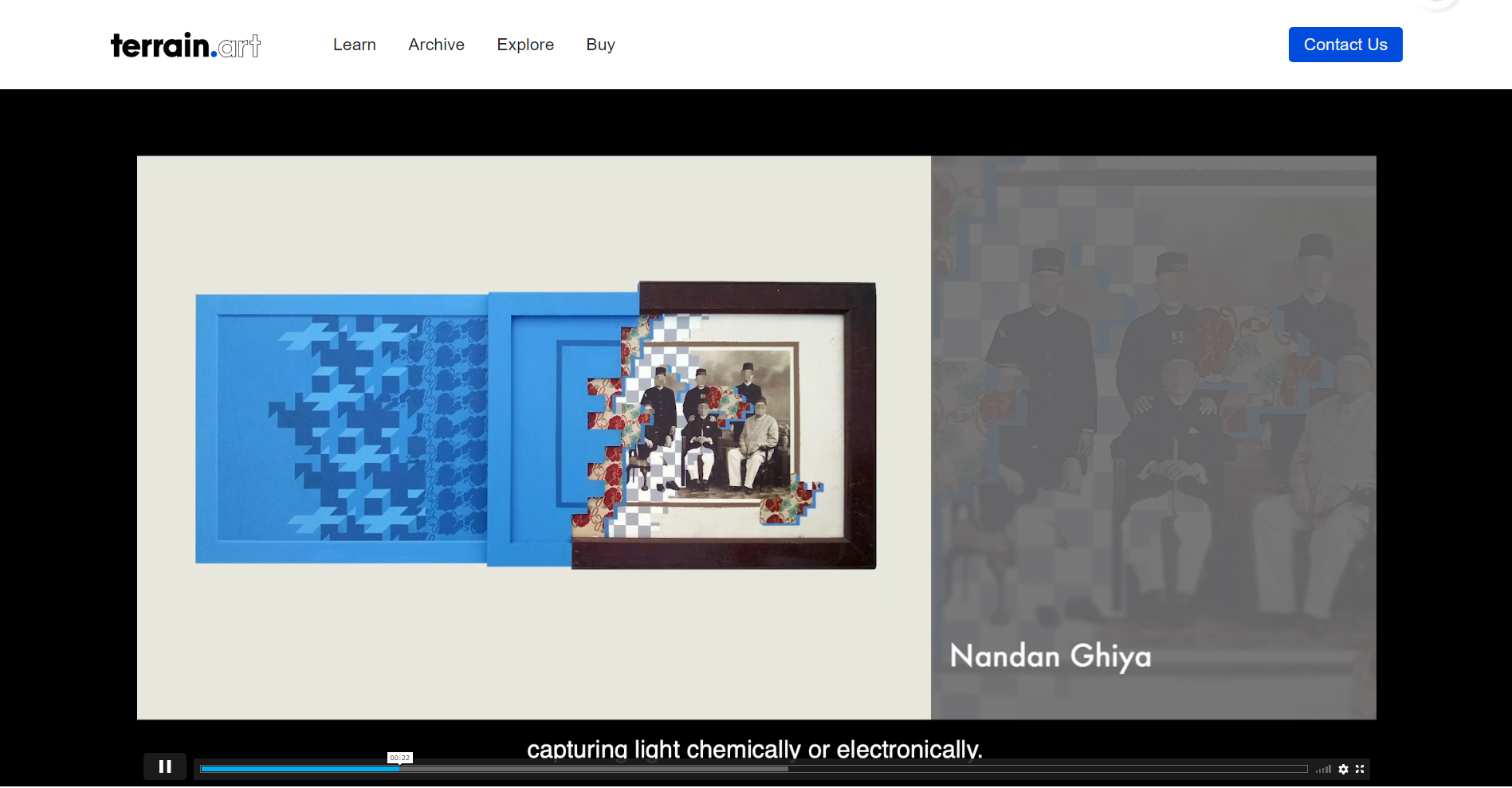

Screenshot of video introduction to photography from Terrain.art

I’ve tried to imagine the audience for Terrain in a few different ways. We have this wonderful intern Avantika Pathania, who is a second-year Art History student at a college in Delhi and works on Terrain’s timeline of art history. I often think of her as our core audience. I also sometimes think of my friends in India who may even be from privileged backgrounds, but just don’t have an entree into the art world and don’t know what questions to ask about art or even whether they are welcome in galleries. And beyond this, I think eventually to reach people who feel intimidated by the arts would be a great thing for Terrain to do.

RA: I suppose a platform addresses the needs of a time, but how does Terrain address a political timeline, especially in India now – with respect to CAA and all the events that followed. How can art help manoeuvre the limits of creative expression at this time?

BC: It’s easy to forget how much happens during the present when we’re all living at home. Eventually, what I’d like the timeline and other resources to have and address is multiple voices. To start this we’ve already invited PhD students from JNU to write short 250-word essays on their research. We want to create a more proprietary interface that would be more user-friendly and also let us have in-depth authored articles embedded in the timeline. I think the answer really is just in having a plurality of perspectives and languages.

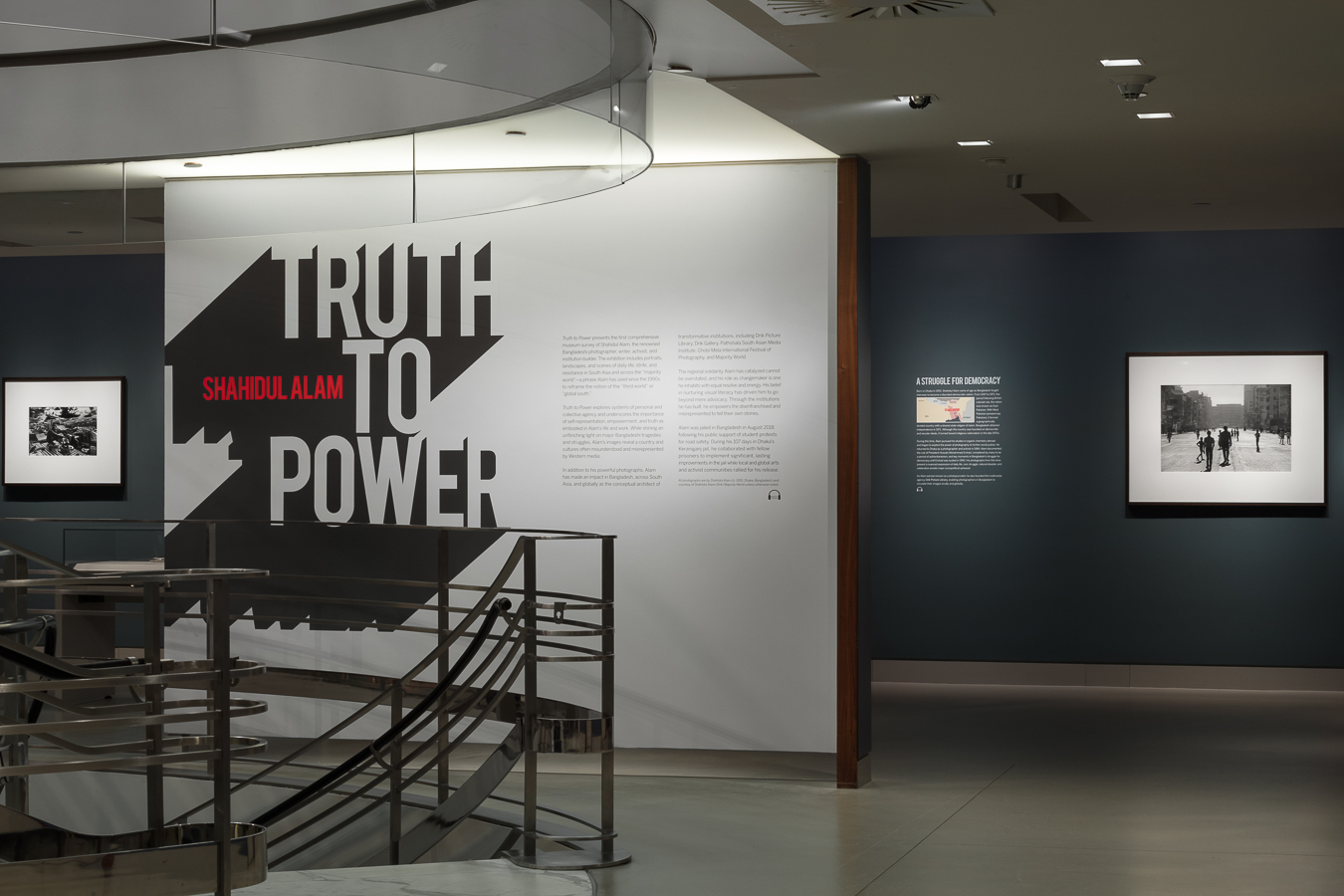

Installation View of the exhibition Shahidul Alam: Truth To Power at the Rubin Museum, New York, November 2019 – January 2021. Curated by Beth Citron.

RA: South Asia as an idea is in free flow, but at the same time, the lines of division are so strong and there are dominant spaces within South Asia that get more representation. Is there an eye to creating a new line of sight associated with dialogues for South Asia, where the Indian subcontinent perhaps does not play a central role? Is there a way of de-centering or is it the sort of reassessment of the centering?

BC: There was initially an ambition that after beginning with India we would move to broader South Asia and then beyond. Practically speaking, though, it takes time to get things right. One of the aspects that I think is successful is that there are artists from all over India – not only urban and not only English speaking – but emerging artists that we’re representing may not have had other opportunities, especially during this difficult time. So I think that we have been effective in terms of de-centering within India. And if we could continue that and expand it beyond India, that would be a good to achieve.

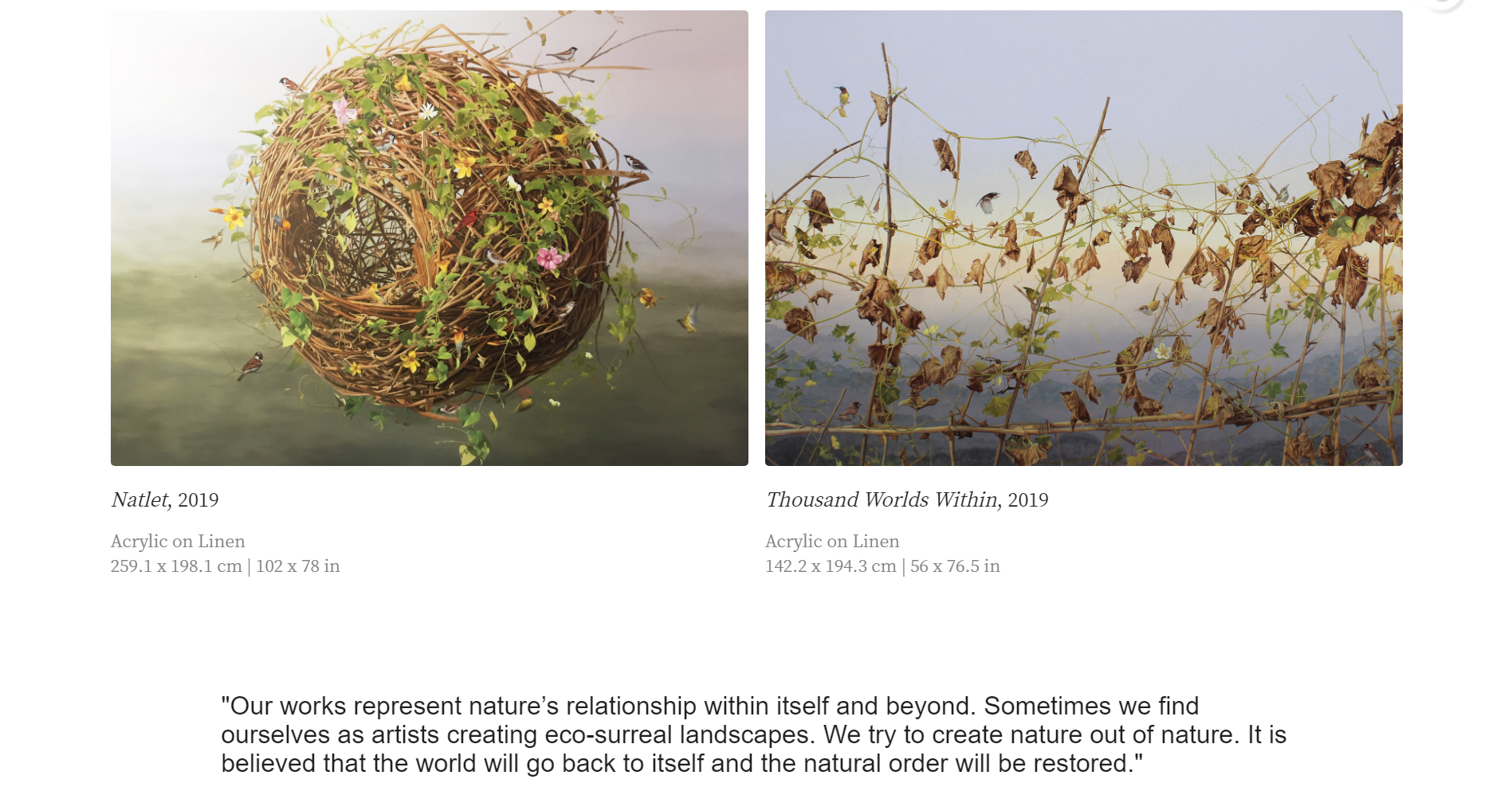

Screenshot of the online exhibition Restoring Order by Susanta Kumar Panda and Ramakanta Samantaray featured on Terrain.art.

RA: How can a digital space communicate the sensory or the sensorial experience of art? Is Terrain then only an interpretive space, a space which invites or opens out different conceptual dimensions? Is it a space where questions of authenticity or authorship are reframed?

BC: I think ideally Terrain would become part of an ecosystem that involves and collaborates with in-person art, viewing, live discussions and live events, even if right now live exhibitions aren’t planned for our space. I think we’re probably looking at a kind of hybrid living for the next couple of years, and there is real opportunity to have a footprint within that. But I, for one, would never want a digital platform to overtake or become the sole way of experiencing art.

I have a young child who can’t yet wear a mask, so my movements are much more restricted right now, and I haven’t been to any museums since they’ve reopened. The only art I really experience is in my own home. The last museum experience I had was seeing Chitra Ganesh’s incredible outdoor installation at the Leslie Lohman Museum and I’ve done only one in-person studio visit during covid. So I personally am quite starved for that in-person experience and looking forward to getting back to it as risk subsides. But the failings of the in-person experience that were there before are going to remain so after this moment is over, and the barriers to experiencing art that were there have only increased unfortunately. And so a thoughtful, intelligent platform that helps people to become comfortable with contemporary art and historical practices should continue to find space for itself in this new world.

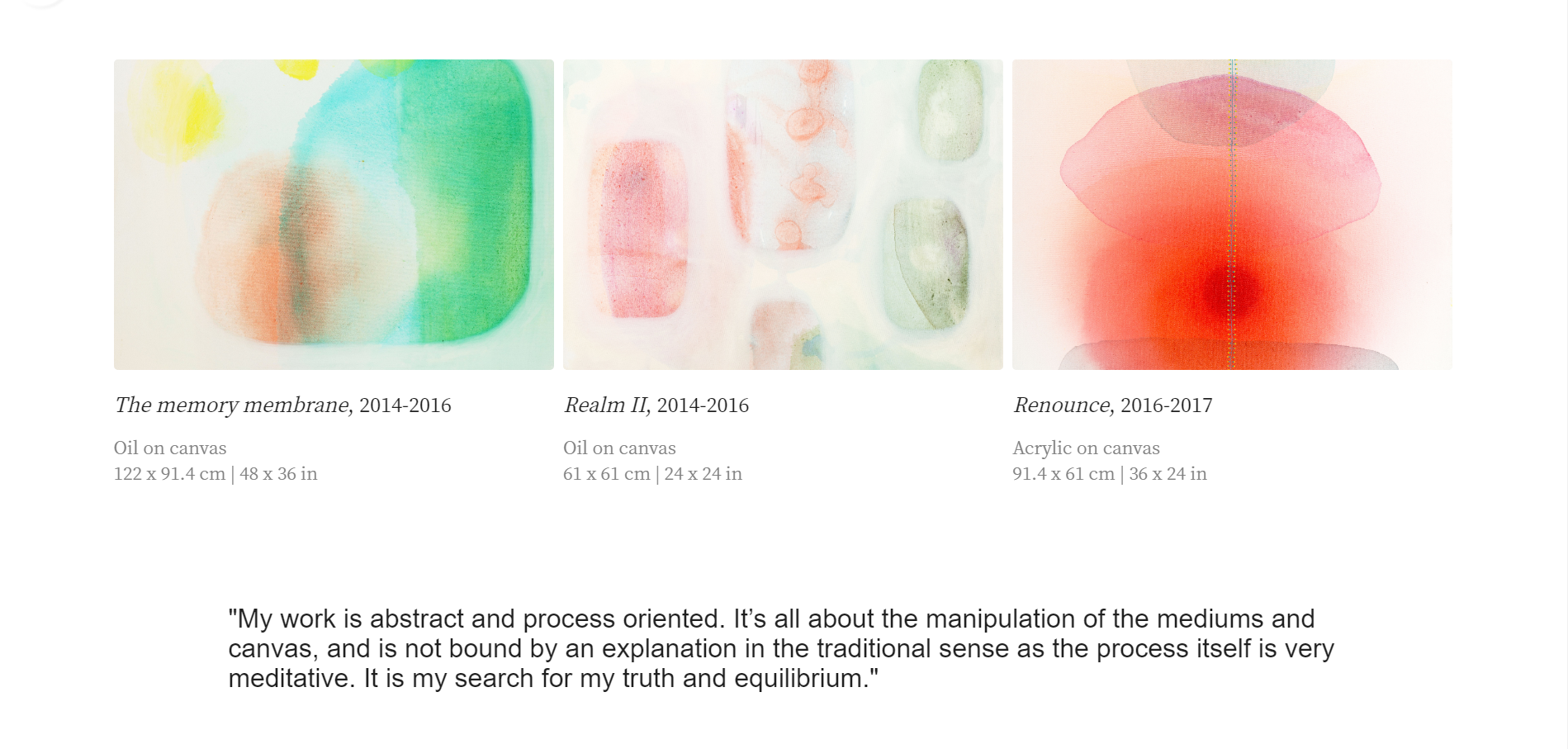

Screenshot of the online exhibition Luminous Fields, by Shristi Rana Menon featured on Terrain.art

RA: As a sense of the archive has changed for you since the Rubin, and has it become a more malleable space?

BC: When I reflect back on the idea of this blockchain powered archive in January 2020, we needed to do this because there was a proliferation of fakes. I look at auction catalogues sometimes and you have to wonder at least when you know that an artist was made only four or five paintings a year, how every auction house would have one or two every season – the math doesn’t always add up.

It’s bad for artists, for collectors, for art history, and disrupts the arts economy. But now I think the idea of the archive is much more malleable and that it can be much more future-oriented. So by working with artists and also educating them about why they need to keep track of their work from very early on in their career, it can be meaningful for artists, it can change the nature of their relationship with their galleries, with their collectors, and with how they put their work out into the world.

Comments