Jazz, Survival, and Imagining History: Interview

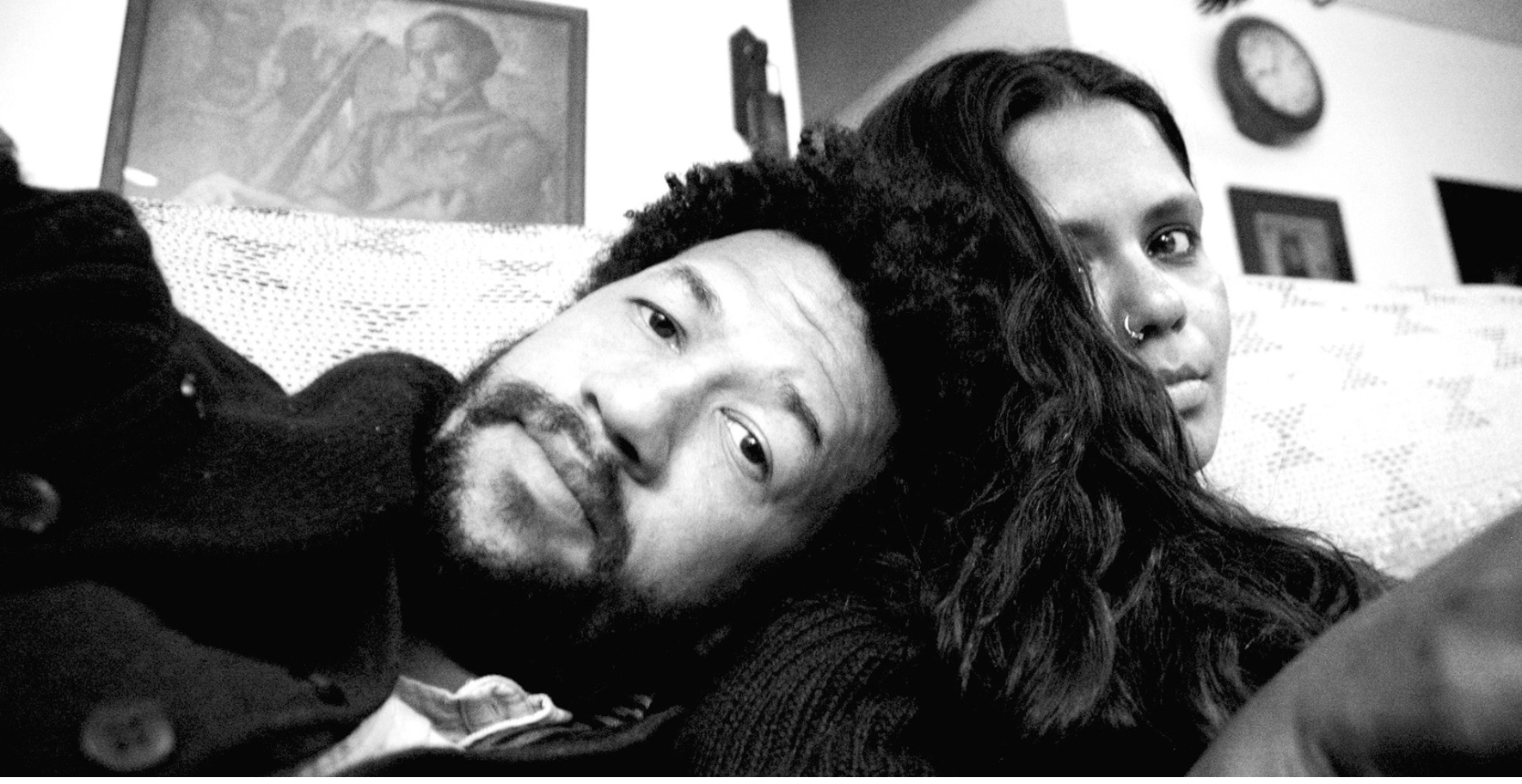

Pigeonhole (2019) Dodd Galleries. Installation views courtesy: Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall.

When histories are imagined, are they simultaneously fictionalized? Or is fiction the voice of colonial power, which often fashions national realities to match its vision? As historian Benedict Anderson (1935-2015) suggests in Imagined Communities (pub.1983), nations themselves were constructed from the proliferation of the vernacular, written word that in turn formed solidarities around nationalistic and uniform discourse(s). How, then, can alternative forms of remembering or new archival modes establish history outside the national and textual, particularly for those who often slip through its cracks?

These are some of the propositions raised and challenged by artists Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall in Pigeonhole (2019), a multi-media installation project that stitches together cultural trajectories of migration and the politics of memory-making through the fascinating figure of Bobby Alam. In imagining the fictional Alam as a Bengali peddler passing as a black jazz musician in the early-20th-century United States, Dasgupta and Marshall utilize the form of a museum retrospective to coalesce truth and myth with playful and powerful effect. By presenting a personal—albeit contrived—history through this lens, Dasgupta and Marshall deconstruct the ways in which prevailing power structures deny authenticity or narrative agency, and also suggest alternative means by which identities can be shaped. In a moment when conceptions of citizenship are being dramatically redrawn along nationalist lines, Pigeonhole‘s microhistory offers possibilities for storytelling outside traditional frameworks.

Pigeonhole, first exhibited at the Dodd Galleries in Georgia earlier this year, will be on view at New York City’s Knockdown Center between June 29th – August 18th, 2019. PIX spoke to Dasgupta and Marshall via email.

What was the genesis of Pigeonhole? And what particularly drew you to Bobby Alam?

Pigeonhole, or Bahauddin “Bobby” Alam’s story, was born out of Priyanka’s research and work that she developed for her MFA thesis. Inspired by the history of Bengalis passing as black in the United States, as recorded in Vivek Bald’s book Bengali Harlem (pub.2013), Priyanka appropriated an image of a nameless, bare-chested Bengali peddler, had him embellished with a 1940s-styled suit and transformed into a black jazz musician. The original image was culled from the 1868-75 phrenological text, The People of India, which she encountered during her research at the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts in New Delhi in 2016. The suited Bengali with his dark skin, facial features, and roughly slicked hair, now looked like a down-on-his-luck black jazz musician.

Originally, the peddler was created as a nod to Bardu Ali, a black Bengali jazz musician attributed as having discovered Ella Fitzgerald, but of whom we couldn’t find an image at the time. The resulting appropriated image resonated so strongly with viewers that we were compelled to become more expansive with our musician, and create a retrospective-level archive around him. As there is such little and fragmented information available about Ali, and it doesn’t seem right to impose imagined details onto a real individual, we decided instead to create Bobby Alam. His fictitious nature gives us the freedom to lend to his life story all the nuances and details that would accompany someone who is deemed worthy of remembering by a historical archive. Over time, as this archive grows more elaborate, we hope that Alam, a parafictional composite created to draw attention to a real history, also engages with the politics of how history is constructed, as well as who decides what is remembered, and how.

The embellished portait of Bahauddin “Bobby” Alam. Courtesy Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall

Can you talk a little bit about the form that this project took on, and the desire to realise it as an installation with objects, furniture, photographs, etc.?

With Alam being derived from the history of Bengali immigrants passing as black in the early-20th century to circumvent the Barred Asiatic Act of 1917 in the US—and in his case, a Bengali passing as a black jazz musician—we’ve tried to design installations that evoke his narrative without being didactic or too literal. For this reason, we decided to approach the telling of his story from the perspective of a museum retrospective and have thus been looking to create the kinds of objects one would generally come across at such places—photographs, handbills, concert posters, clothing, instruments, notes, video, and sound recordings. We wanted these items to be presented in-situ and decided to use the site of a “juke joint,” where upcoming musicians of the time would have performed.

We use the wooden shipping palette as a design element in our construction as it simultaneously resembles the clapboard in the structure of juke joints while alluding to Alam’s merchant navy past, as well as the capitalist reduction and commodification of self that Pigeonhole seeks to confront. The multidisciplinary nature of the installation contends with the hegemony of the written word as the official apparatus of historical recording. Through the incorporation of multiple media and methods of representation, Pigeonhole resists the linear, singular perspective ascribed to the document and its imposition, in favour of the multifaceted complexity of a history preserved and circulated through multiple lenses. Moreover, the appropriation of archival photographic material within the work, and the adoption of specific historical tactics of embellishment and disguise, raise critical questions around the implementation of photography as an apparatus of the state and a phrenological tool to restrict and control the colonised.

What you’re suggesting is a disruption of museumized display practices through a self-reflexive co-option of archival tactics. Can you share how you delineated these existing strategies of visualization—what were some examples you were looking at or working against?

A consideration of the relationship between image circulation and power is definitely a critical component of our practice. We are particularly interested in the tactic of embellishing photographs with paint—popular with the British in India, and Indian nobility as well—to mask physical ailments, or present favourable “truths.” A particular image that comes to mind in this regard is the photo-montage commissioned and circulated by Lord Curzon following the Delhi Durbar of 1903, to present an image of an orderly, unified front comprised of members from both the Empire and her colony. The image, “Imaginary Scene of Lord Curzon and the Duke of Connaught, Coronation Durbar, Delhi,” despite its obvious construction has a visual resonance that is provocative. This tactic of trespassing between document and fiction, and the power that it wields, is definitely something that we consider and contend with in our own constructions, as we develop and embellish our parafictional character, Bobby Alam. Moreover, in our decision to cull and appropriate images from The People of India manuscript for our portraits of Alam and his friends, we critique the staged nature of these volumes as well, and use it to point to the reductive, stereotypical image of the “Bengali Peddler” that Alam is ultimately trying to escape.

Pigeonhole (2019), Dodd Galleries. Installation views courtesy: Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall.

In allowing for complexity beyond the written document, does the adoption of this retrospective voice also attempt an institutional legitimization for figures like Alam, otherwise lost to history?

Our endeavour is to critique the institutional practices of controlled and compartmentalized collection and preservation, and the prevailing hegemonies which dictate who and what these collections highlight. Our retrospective-styled collection for Alam adopts the structure of an institutional archive not with the desire to be embraced by it but to disrupt. The individual objects within our archive are nuanced, complex, and evade singular narrative or linear perspective from which the collection can be contained. Ultimately, for an institutional legitimization, our retrospective must, at some level, be reduced, however, the hybridity that lives at its core, refuses the same.

What’s fascinating and perhaps most challenging about manifesting personal histories like these is the question of how to deal with scale. How did you think through presenting Alam’s story as distinctively singular as well as part of a larger historical arc? How comprehensive or selective did you have to be about the material?

The scale of the installations has really been defined by the fact there are only two of us and our resources are limited. As a result, we have needed to be realistic about what we can accomplish and what items would resonate the most with viewers. At present, our decisions regarding material reflect the trajectory of Alam’s music career and our research around what memorabilia from other musicians of the ’30s and ’40s in the US has been preserved, or is deemed worthy of preservation.

Additionally, our design ethos of creating spaces that make a physical impression and generate a physical memory for the participant, making them an active viewer, also impacts the scale. It is important to us that the work resonates on a level beyond the visual, and the structures we create are designed specifically to generate such a physical response from our audience.

Passing, whether in terms of gender, caste, or race and ethnicity, is often a means of survival, as in Alam’s case, as well as a way to perhaps create “inauthentic” solidarities from places of privilege or otherwise. Ultimately, it raises an important question of authorship, agency, and who can rightfully make certain truth-claims. Can you explain how Alam’s passing took shape, and what approaches you adopted in presenting these complexities through the installation?

While issues of authorship and cultural appropriation are very of the moment, they’re not relevant to Alam or the passing of Bengalis immigrating to the United States at the time, in that they were not passing within the black and latino communities that harboured them. They passed in the larger white world as a more familiar, dark Other of black or latin descent instead of the exotic, dark (and illegal, owing to the Barred Asiatic Act of 1917) Other of Indian. This is an important distinction and central to the impetus behind our work: Alam is not cooning or a minstrel. He is not making claims to speak someone else’s truth; he is speaking his own truth in the guise of “they all look the same.” When the black and latino communities accepted Alam and the other Bengali men, they knew who they were. Moreover, as the black community was, right from the outset, a collection of different African tribes, ethnicities, languages, and cultures, these men signified just more of that. However, to the powers that be that lacked an eye for nuance, they represented just another brown or black face. It is this complexity of self in the face of a commodifying, indifferent simplification, and the pigeonholing that accompanies the trading of one stereotype for another in the struggle to live on one’s own terms that Alam’s passing is trying to address.

Pigeonhole (2019), Dodd Galleries. Installation views courtesy: Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall.

To stick with passing for a moment, you say that Alam’s configurations of self occupy a space between reality and fiction, or rather, complicate that binary. Can you speak more about that? Does Alam symbolise an imagined, utopian identity or is he a symptom of political narratives often drawn on fictions willed into reality by the state?

None of the above. Much like any good movie or novel that references reality, Alam is a composite of real people, created to visualize a history that has only been preserved in fragments, and to give the authors more freedom over the narrative. The larger narrative in this case is the stories of the Other in America, and the desire to present a more transparent look at the “American Melting Pot,” and the contradiction in the Americana ideal of simultaneously welcoming the unwanted, to the reality of the US government actively barring those same unwanted, both historically and in the contemporary moment. If anything, Alam’s story is a critique of the utopian ideals of belonging that exist alongside the contradictory politics of assimilation in the United States, and the continued perpetuation of notions of singular identities and similar polarizing actions of the state.

As you gear up towards the latest realisation of Pigeonhole at the Knockdown Center in New York, can you tell us what’s changed since the last one, what you may have modified, and finally, what you hope the afterlife of this project might be?

Going back to your question of scale, as this is the second iteration of Pigeonhole, this means that we have had time to expand the archive, include more photographs, music, and video, and have “found” Alam’s resonator guitar. As our installations are site-specific, we’ve adapted the layout to capitalize on the space and added a collaborative, performative element that pulls from the Knockdown Center’s other role as a performance venue. During the course of the exhibition, we will have live performances featuring music that inspired, was performed, or has been inspired by Alam.

As for future iterations of the work, Alam’s story is that of the immigrant in America. It is also a statement on history and the archive, and questions what is remembered and how. As we continue to develop our practice, we are looking for opportunities to explore and expand upon these aspects of our politics in greater depth.

An excerpt from If the Suit Fits from Pigeonhole (2019). Courtesy Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall

Priyanka Dasgupta and Chad Marshall’s practice draws from archival texts, sociological conventions, and postcolonial studies to examine power in the United States, and its relationship to appearance. Exhibitions of their work include Pigeonhole, Dodd Galleries, University of Georgia (2019), Sunroom Project Space: Paradise, Wave Hill (2018), How to see in the dark, Cuchifritos Gallery (2018), In Practice: Another Echo, Sculpture Center (2018), Loving Blackness, Asian Arts Initiative, Philadelphia (2017). Residencies include Artist Studio Program, Smack Mellon (2018) and AIRspace, Abrons Arts Center (2018). Dasgupta and Marshall are recipients of the 2019-2020 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, and are currently working towards a solo exhibition at Knockdown Center, New York, opening on June 29, 2019.

Comments