Life after Ritwik Ghatak—Part 2

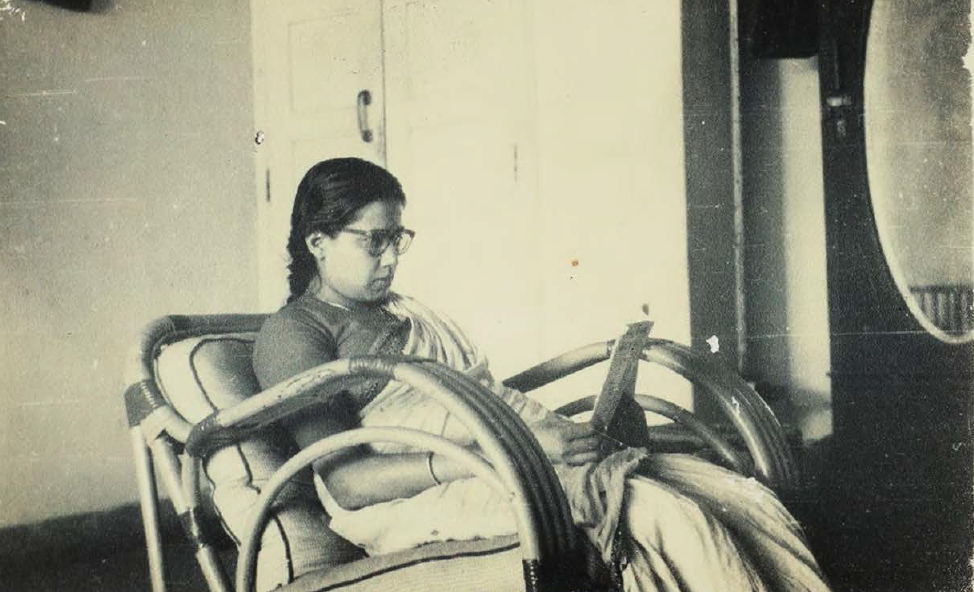

Surama Ghatak, 1960s, Mumbai

It was 1965, and the lives of Surama (endearingly, Thamma) and Ritwik were at a cusp.

He wrote a letter to Thamma asking her opinion on starting a new life with Meera Jana, with whom he had forged an emotional bond. Naturally, Thamma was very hurt by this so-called altruistic note or gesture, and tore the letter, moving instead to Shillong – away from the mental and physical stresses of the day-to-day.

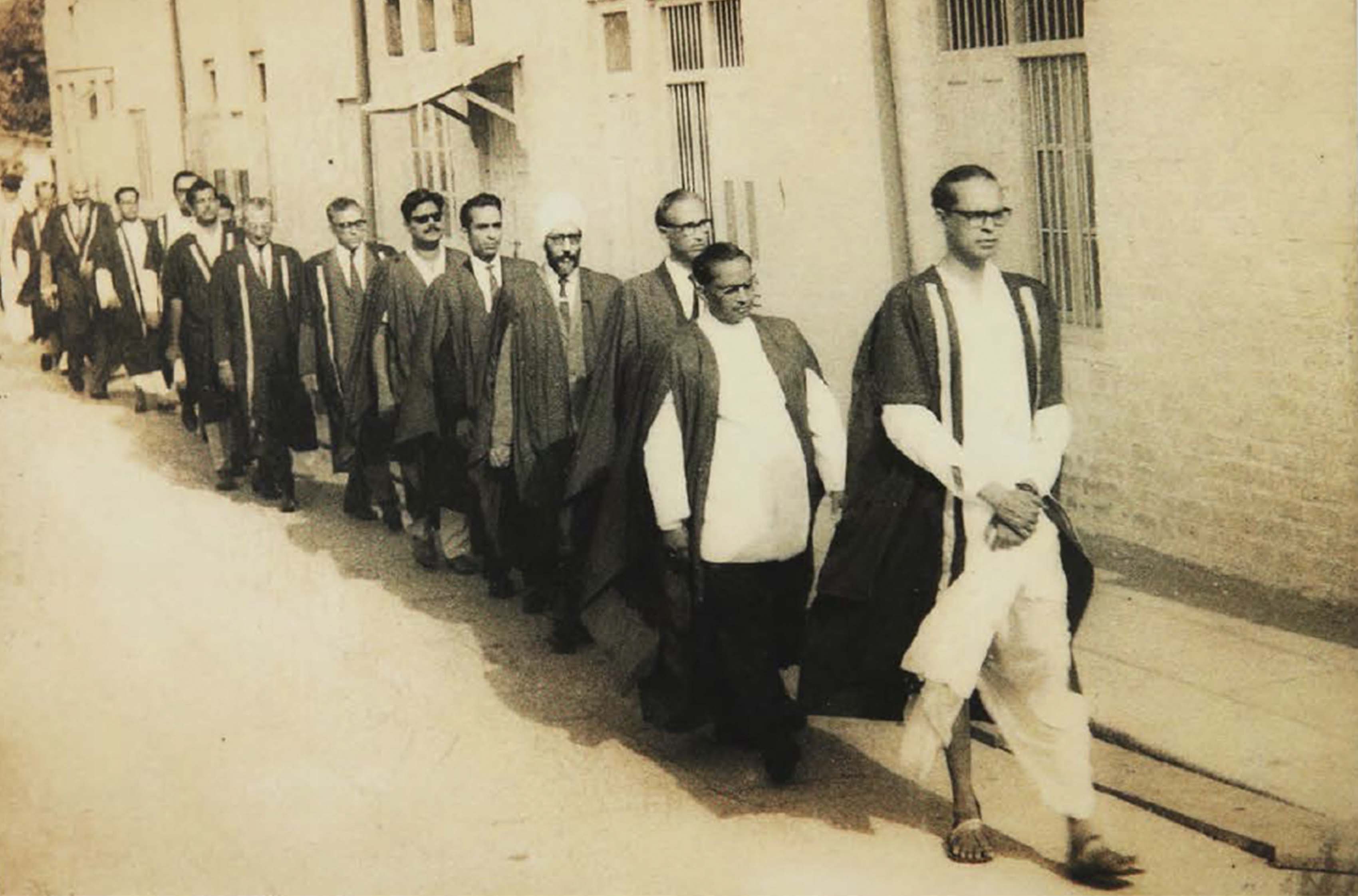

Ritwik, realising the seriousness and insensitivity of what he had done, discussed the delicate situation with Meera Jana. She was a mother herself, and suggested that he remain with his family. Thus, set on the path to reforming himself and bringing stability to his life, which also included rehabilitative treatment – he joined the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) as Vice President the very same year.

Ritwik Ghatak at the head of the line, 1965, Film and Television Institute of India, Pune

Ritwik Ghatak at the head of the line, 1965, Film and Television Institute of India, Pune

Thamma mentioned that she fell severely ill at this time – developing dark patches on her body with periodic panic attacks, until she was hospitalised. Though their relationship had changed forever, the thought of a balanced co-existence, remained extremely desirous.

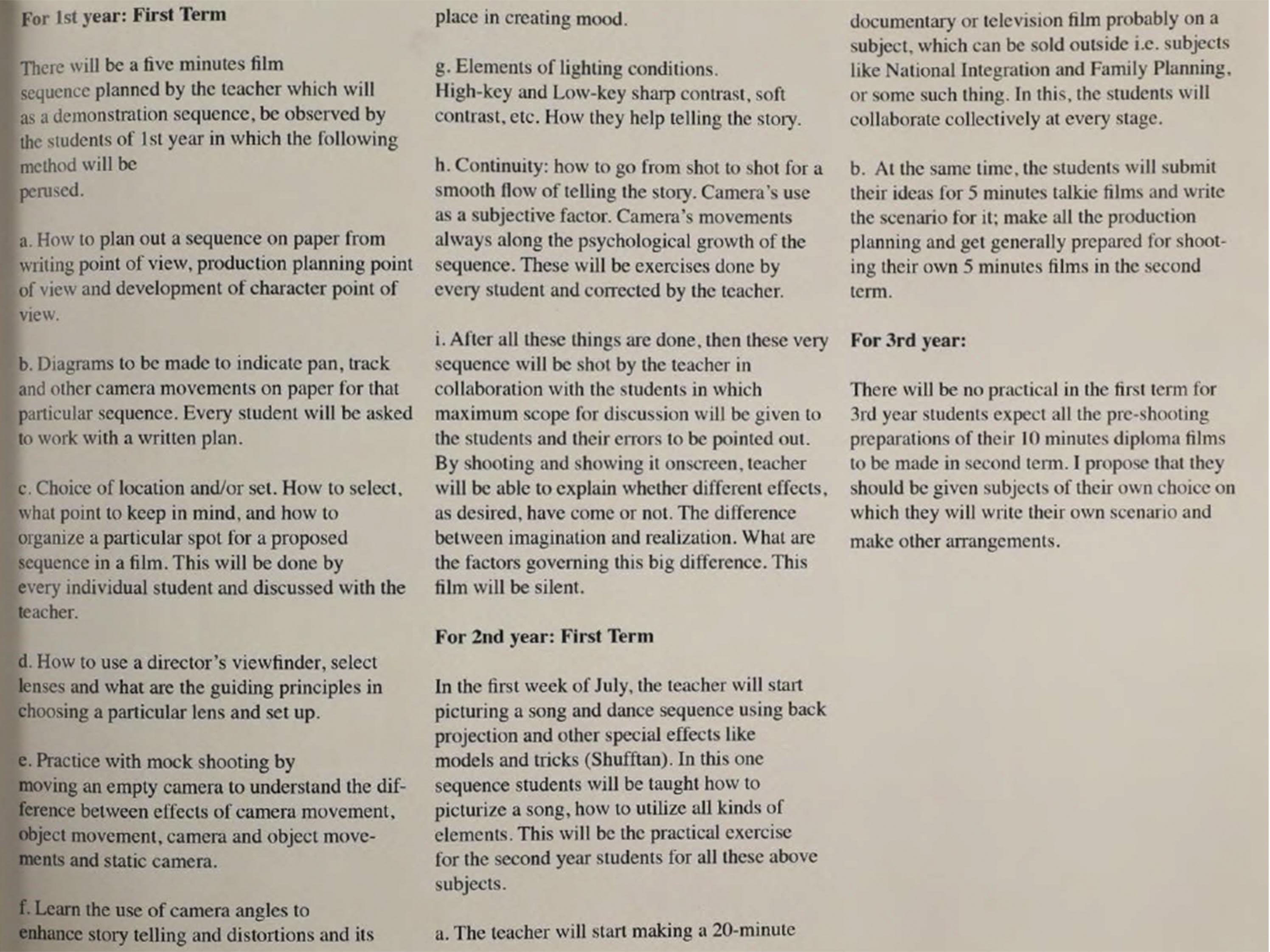

At Pune, Ritwik, once more proved charismatic and inspiring to his students, and proposed a complete restructuring of the Direction programme, emphasizing practice over theory. (Below are some details of the curriculum restructuring proposed by him, reproduced from the publication Life After Ritwik Ghatak). But inspite of being a formidable force in the department, a desk job didn’t suit him – he was overwhelmed by the administrative paperwork.

Curriculum proposal for the Direction Programme at FTII by Ritwik Ghatak, 1965

Curriculum proposal for the Direction Programme at FTII by Ritwik Ghatak, 1965

When Ritwik visited Shillong, Thamma believed that he had come to invite her and the children to live with him in Pune. Instead, they were informed that he had resigned from his post. This left her devastated. While in Shillong, Surama remembers that he locked himself in his room for three days. The light would always be on and he would keep talking to himself; sometimes even screaming. She would often come home to find him partially, or completely unconscious after having consumed too much liquor.

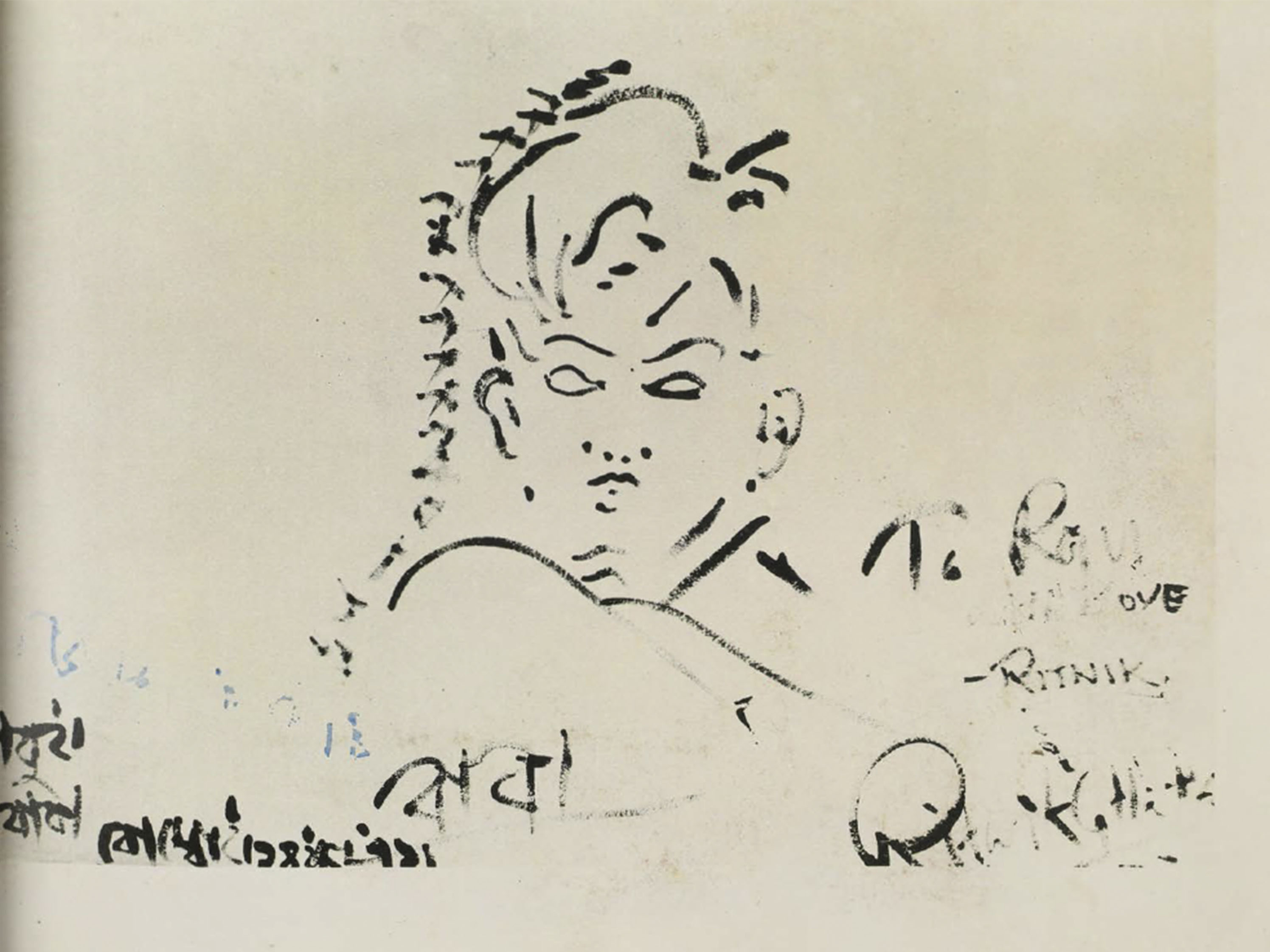

Sketch of his son, Ritaban Ghatak by Ritwik

Sketch of his son, Ritaban Ghatak by Ritwik

The family soon moved back to Calcutta, but from a professional standpoint, the relationship with and to his contemporaries, became strained. He took this very personally as he felt that everyone failed to understand his voice or support his creative bent of mind. Ritwik however, continued to write – short stories, fiction and other essays, with a pace that was no less than prolific. In his lifetime, he wrote almost 50 essays on film covering every aspect of cinema. Night after night he obsessively scrawled in prose and spoke to Thamma of his plans for the future. But with time, the antidote to his changing temperament – a continued focus on work – didn’t alter his predicament but only exacerbated the fissures, the ruptures. In 1969, he was admitted to Gobra Mental Hospital in Tangra.

It was painful to see him like this. His vision was so different, not many people could understand him. Cinema in our society is more of an entertainment. My husband was not an entertainer rather he dissected our society and has shown that in his films. He himself said ‘I do not believe in the label entertainment nor do I accept slogging’.

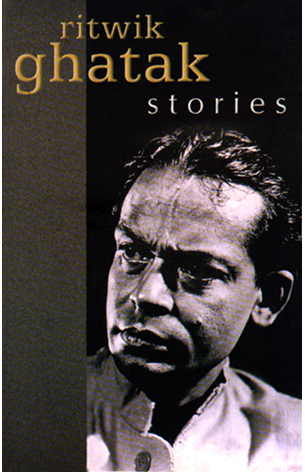

Book cover of Ritwik Ghatak Stories, Translation by Rani Ray Srishti

When Ritwik was hospitalised, the family’s economic situation was dire. Thamma tried continuously to find a job, but was unsuccessful. It was, eventually, Ritwik’s cinematographer for films like Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-capped Star, 1960) Komal Gandhar (A Soft Note on a Sharp Scale or E-flat, 1961), and Subarnarekha (Streak of Gold, 1965) – Mahendra Kumar, who helped the family financially. Many years after Ritwik’s death, Thamma discovered that Mahendra had intended to have a relationship with her, over which Ritwik and Mahendra had fiercely argued. On one occasion, Ritwik was badly injured. Thamma resented Mahendra for this, which also obliterated his benevolence in their time of need.

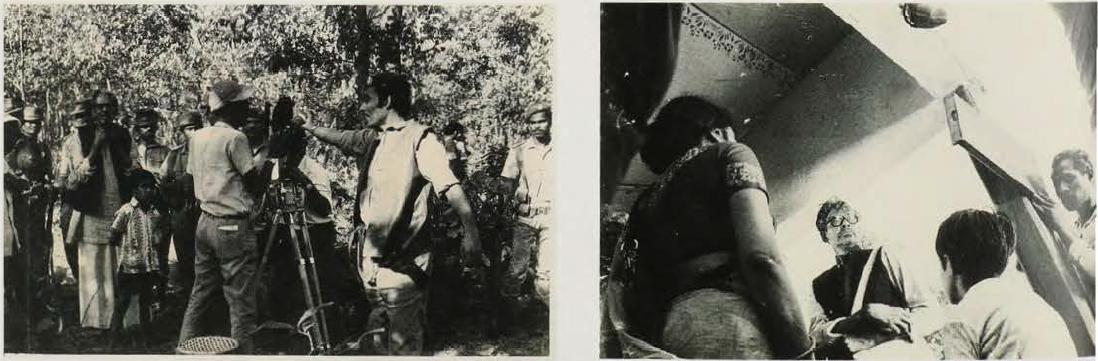

On the sets of the film Subarnarekha (1965)

On the sets of the film Subarnarekha (1965)

In 1969, Ritwik was not only suffering from alcoholism, but possibly a form of dementia as well – hallucinating, delirious, depressed and even schizophrenic. A decision was now made that would alter his condition forever.

The doctors suggested electric shock therapy, as a more extreme and ‘effective’ step in his recovery treatment – and Thamma, unfortunately, did not oppose it.

It led only to further estrangement and disorder. He said to Thamma on occasion, that he saw haunting images of women covered in blood, and sometimes referred to them as the “spirit of Bangladesh”. He was injected heavily every day for a period, repeatedly rendering him unconscious. He even told Thamma that he was no longer able to think clearly and wished to go home. But his time at the hospital continued given the domestic situation remained uncertain, if not unresolved.

Hearing about this phase of Ritwik’s life, naturally troubled me. I often wondered— had Thamma succumbed to the situation, unable to reason her life or the practicalities of it in order to care of Ritwik? Was she humiliated and unable to forgive him? Though the love between them had gradually waned, she still respected him as an artist – his articulations of the evils of social injustices, especially those perpetrated against women. However, could that reconcile with his treatment of Thamma which seemed erratic and unfair?

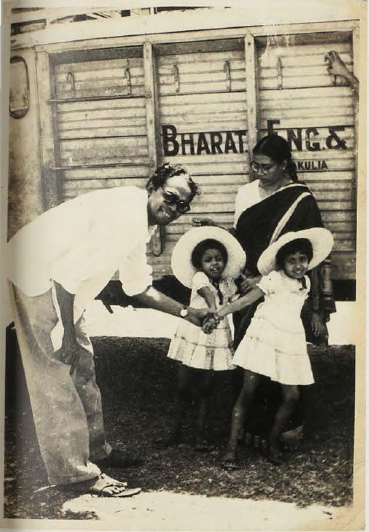

Ritwik and Surama with their children

Ritwik and Surama with their children

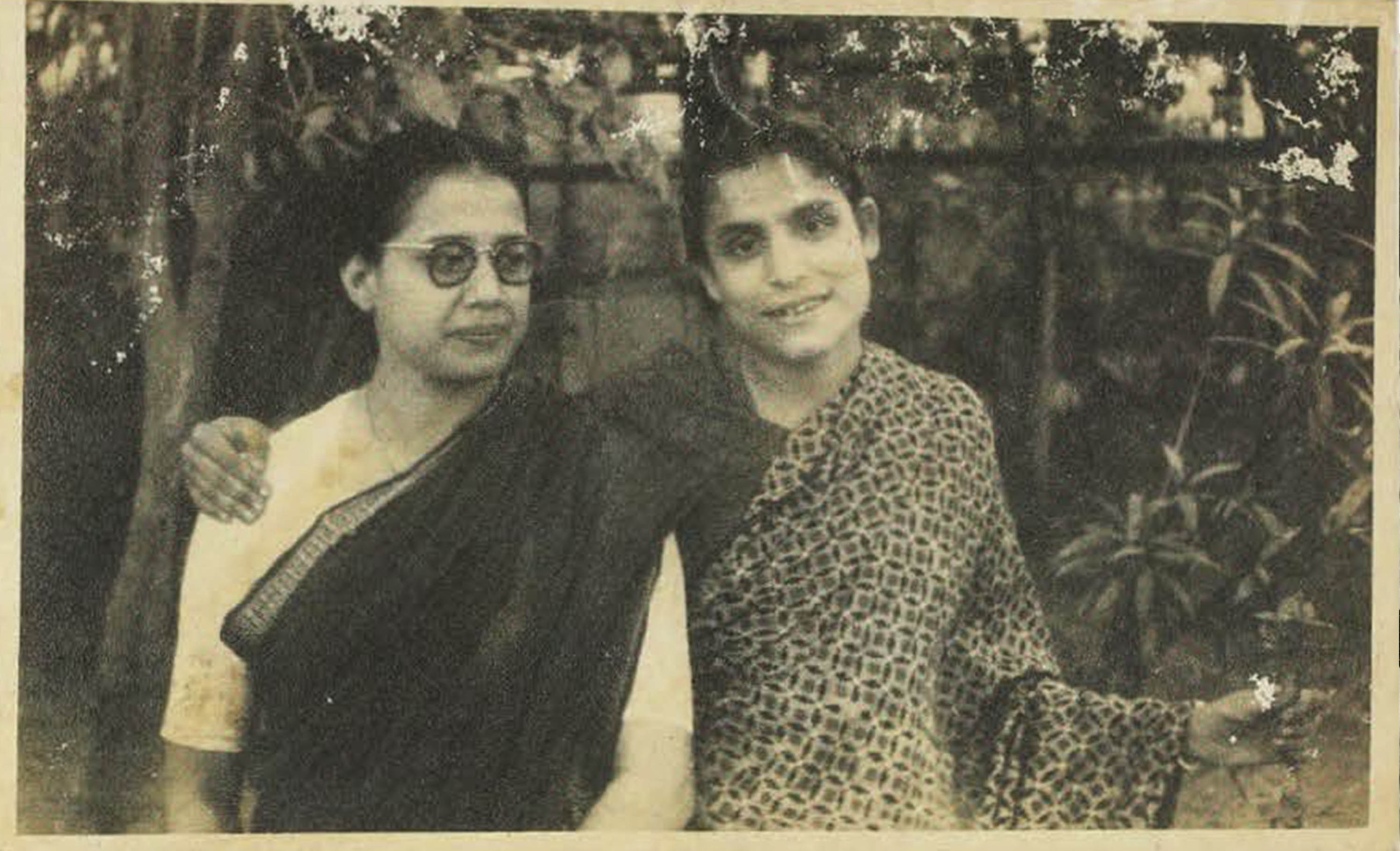

Surama with a friend

Surama with a friend

As time went on, so did the public interest in his condition and soon members of the Writer’s Building objected to the inhumane treatment he was undergoing. Ritwik was finally discharged within the month and returned to his home in Calcutta.

In December 1969, Thamma too returned, expecting a changed man. Instead, life relapsed once more into another version of an earlier routine. He accused her of being an unsupportive wife, unwilling to help with his career. Thamma retorted by voicing his failure to support dreams of her own – ones she was foregoing for him.

Returning home one day, she found him lying, inebriate, with members of the Kalighat crematorium, discussing the practicalities of his demise. Thamma, embarrassed and at her wits end, packed her belongings and left with their three children for Sainthia. She had secured a job as a schoolteacher and her decision was irrevocable.

My aunt, Samhita, Ghatak’s elder daughter recalled that this shift left their father utterly heartbroken. He tried to stop them.

On the sets of Jukti Tokko Aar Goppo (1974)

On the sets of Jukti Tokko Aar Goppo (1974)

Introduction video clip to Jukti Tokko Aar Goppo (1974)

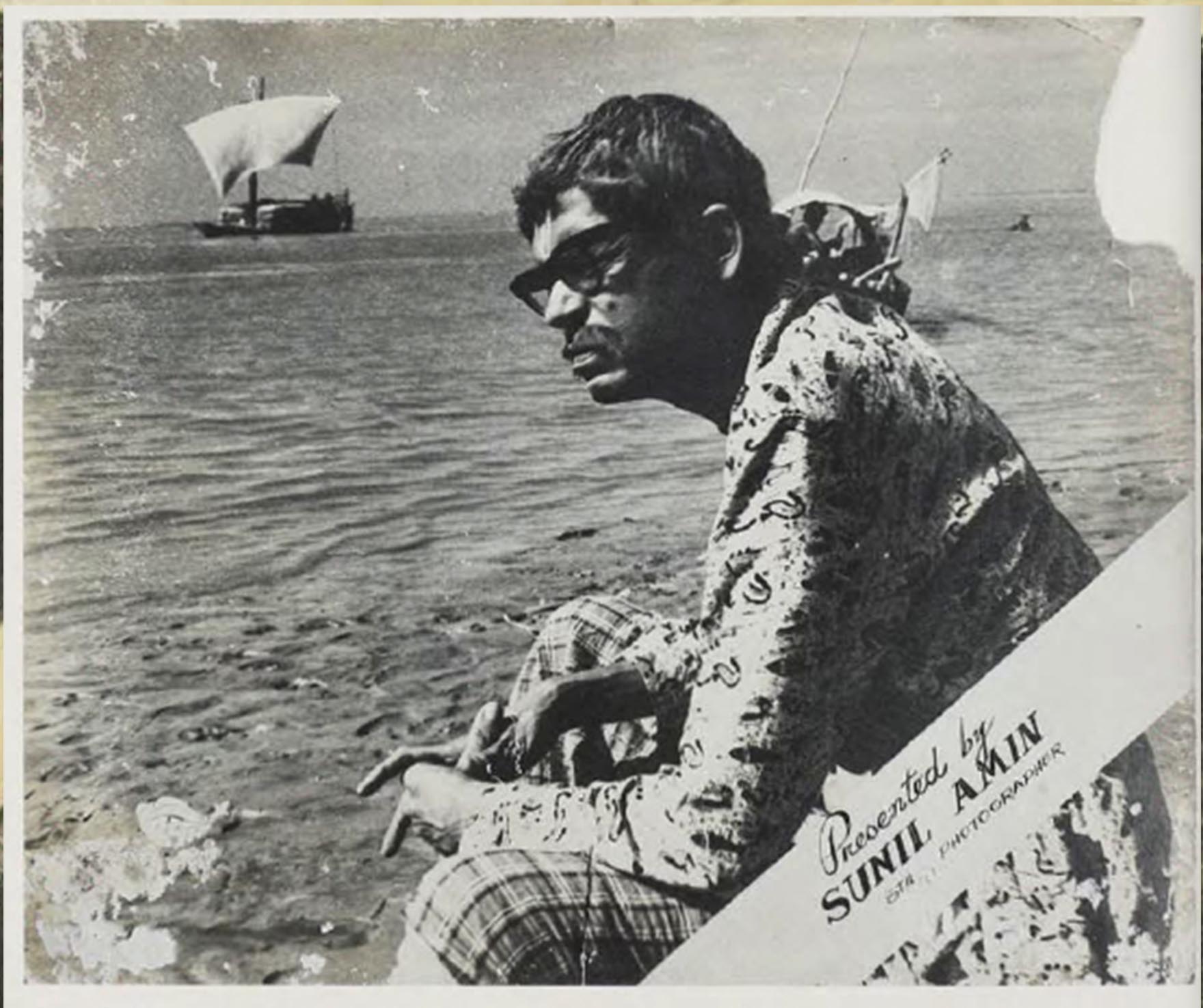

Ritwik Ghatak in the film Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973). On his way to Bangladesh, watching river Padma. The photo was taken by cinematographer Mahendra Kumar who accompanied Ghatak and reported that Ghatak cried while looking at the river. He shared an emotional bond with Bangladesh is reflected in all his work.

Ritwik Ghatak in the film Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973). On his way to Bangladesh, watching river Padma. The photo was taken by cinematographer Mahendra Kumar who accompanied Ghatak and reported that Ghatak cried while looking at the river. He shared an emotional bond with Bangladesh is reflected in all his work.

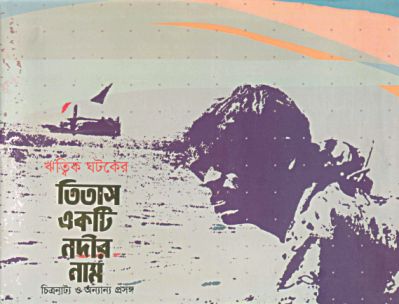

After Thamma left for Sainthia, Ritwik remained in Calcutta and began to live with Biswajit Chatterjee, a noted Bengali singer and actor of the time, and his wife. They advised him well. It was only months later that Ritwik went to visit his family in Sainthia. Things appeared to have improved as Thamma remembers being overjoyed to see him having returned to a somewhat normal schedule. It is at this time that he wrote the script for Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (A River Called Titas, written and released in 1973) and Jukti Tokko Aar Goppo (Reason Arguments and a Story, written in 1974 and released 1977).

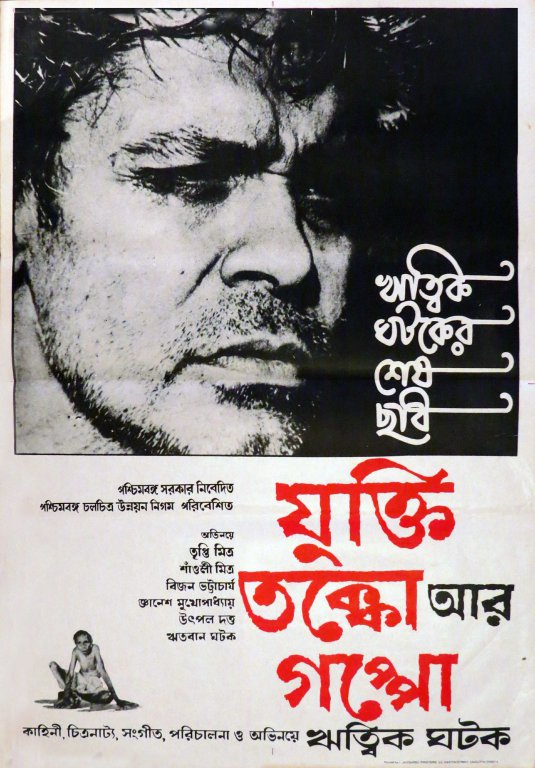

Poster for Jukti Tokko Aar Goppo (1974)

Poster for Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973)

Surama and Ritwik had resolved their differences for the time being. Thamma excitedly wrote to P.C. Joshi, General Secretary of the Communist Party of India (CPI) who also helped form IPTA in 1942, regarding a transfer to Calcutta, in order to start working there full time – but there was little encouragement.

The couple eventually began to live separately again.

Ritwik Ghatak on the sets of one of his films, with a stained kurta

Ritwik Ghatak on the sets of one of his films, with a stained kurta

With the passage of time, between 1973-74, there was another blow. Ritwik was diagnosed with tuberculosis. On one occasion, Ritwik fainted after finishing Titas, and so Thamma instantly travelled to Bangladesh. His condition was deteriorating swiftly.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, (who was introduced to Ghatak when he was theatre activist in Santiniketan, and who later worked on a documentary on Mrs. Gandhi in 1972) sent her personal helicopter to bring him back to India and Ritwik was immediately hospitalised at the Calcutta Medical Hospital. Uttam Kumar, a noted Bengali actor, contributed financially towards his treatment this time round, and Thamma travelled back and forth between Sainthia and Calcutta to check on his general condition.

Soon, Ritwik was discharged and started living with Biswajit Chatterjee in Calcutta again.

Ritwik Ghatak, 1970s

Ritwik Ghatak, 1970s

By 1976, with some resources in hand, and before the release of his film, Jukti Tokko Aar Goppo, Ritwik made plans to go to Malaysia, for reasons unknown, and was even considering buying a house in Calcutta. He wrote to Thamma, saying that he wanted to start a new life – a secure one. When I asked Thamma about how this made her feel, she said that she could no longer bring herself to accommodate the idea of a new life that could once again, end in tragedy. She had lost all hope.

She was not mistaken.

In early January 1976, Ritwik visited his family in Sainthia. Thamma recalls, that he did not speak much that day but he heard their son, Ritiban sing and held him in a long, tight embrace. Inspite of the time spent apart, he chose not to live with them but instead, stayed in an inexpensive hotel in town.

His financial situation was most likely desperate, since he returned the next morning and asked Thamma for a loan – which after heated deliberation, she agreed to give him. Thamma remembers that he seemed absent-minded and did not speak much, again. This was the last time she saw him.

Soon after his return to Calcutta, Ritwik was once again admitted to the Calcutta Medical hospital and on this occasion, Thamma refused to visit him.

Less than a month later, on 6 February 1976, Thamma received news of Ritwik’s death. Around the same time, Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee offered Surama a position in a Government School in Calcutta. So she finally came back to Calcutta, but first, to cremate her husband.

I was dumfounded when I heard the news. All I could remember was him saying he would not come back alive if he went to the hospital again. This came true. We rushed to Kolkata as soon as I got the news. I was completely lost but had to remain strong.

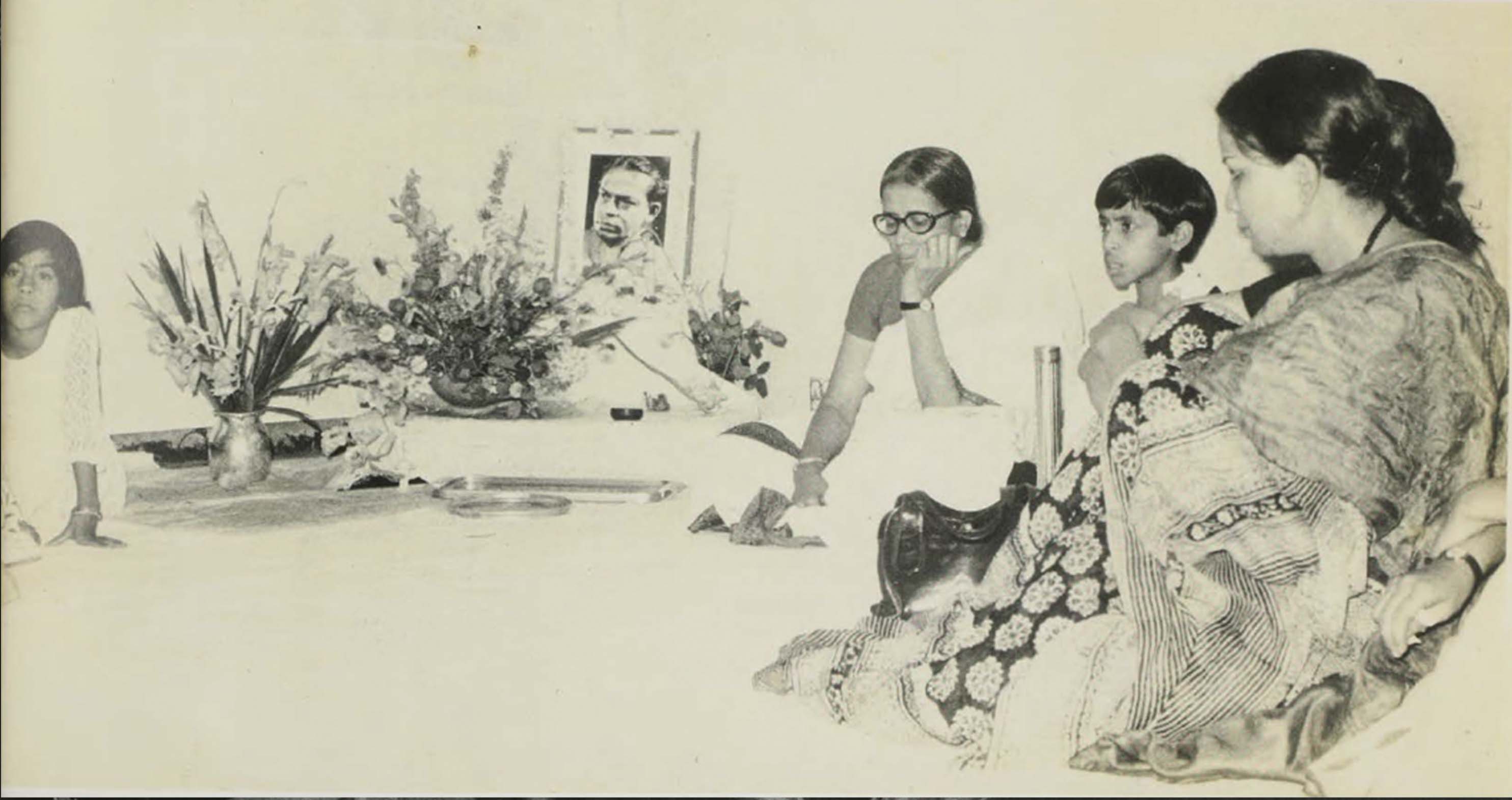

Prayer meeting for Ritwik Ghatak, 1976

Prayer meeting for Ritwik Ghatak, 1976

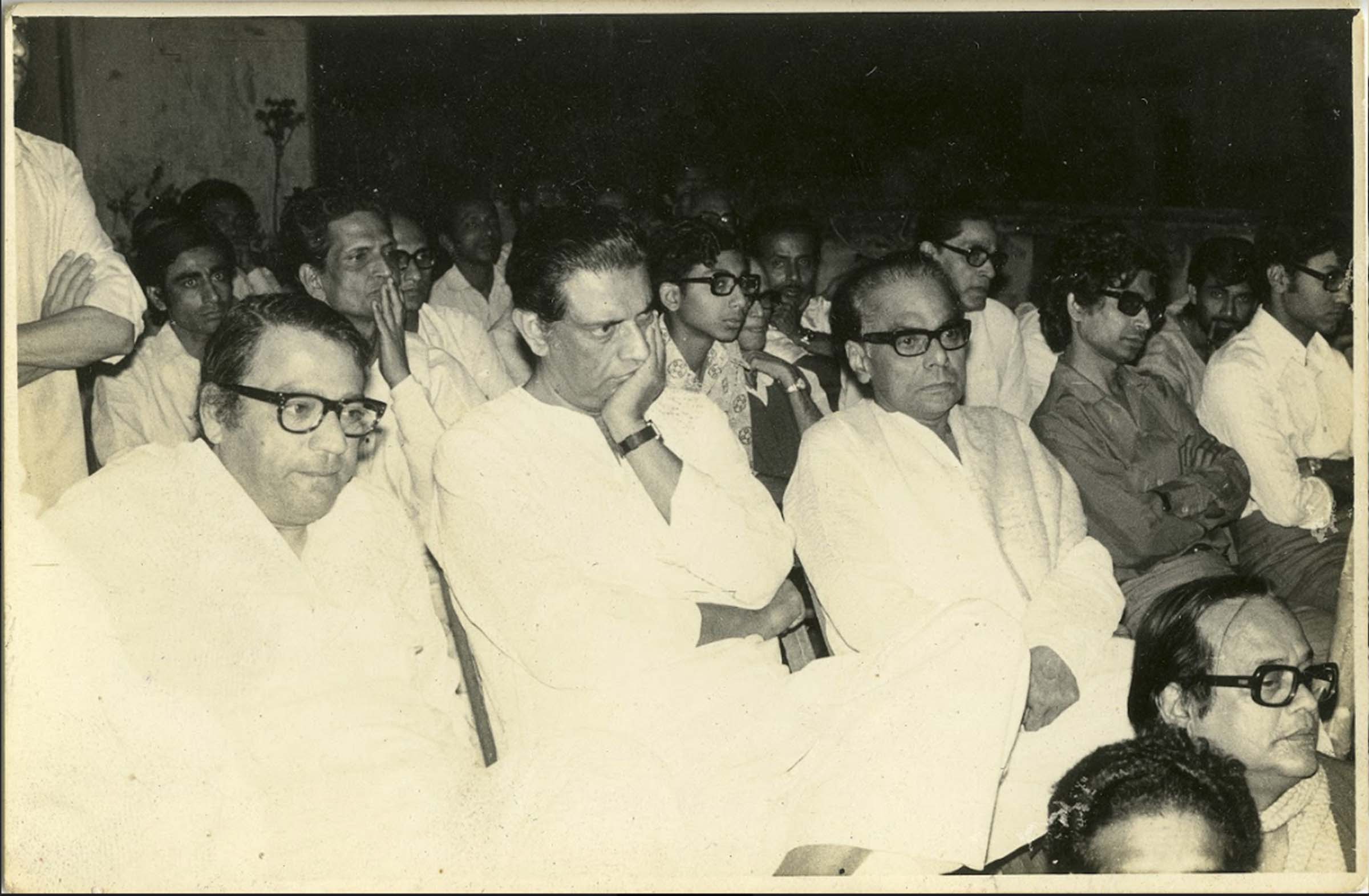

Satyajit Ray and others at the prayer meeting for Ritwik Ghatak at the residence of Mrinal Sen.

Satyajit Ray and others at the prayer meeting for Ritwik Ghatak at the residence of Mrinal Sen.

Today, forty-two years after his death, Ritwik Ghatak remains a maestro of Indian cinema. Accounts from Thamma make me believe that his work never found adequate support, and the common people for whom they were made, couldn’t appreciate the full breadth of his contribution given their defined reach – nationally and internationally.

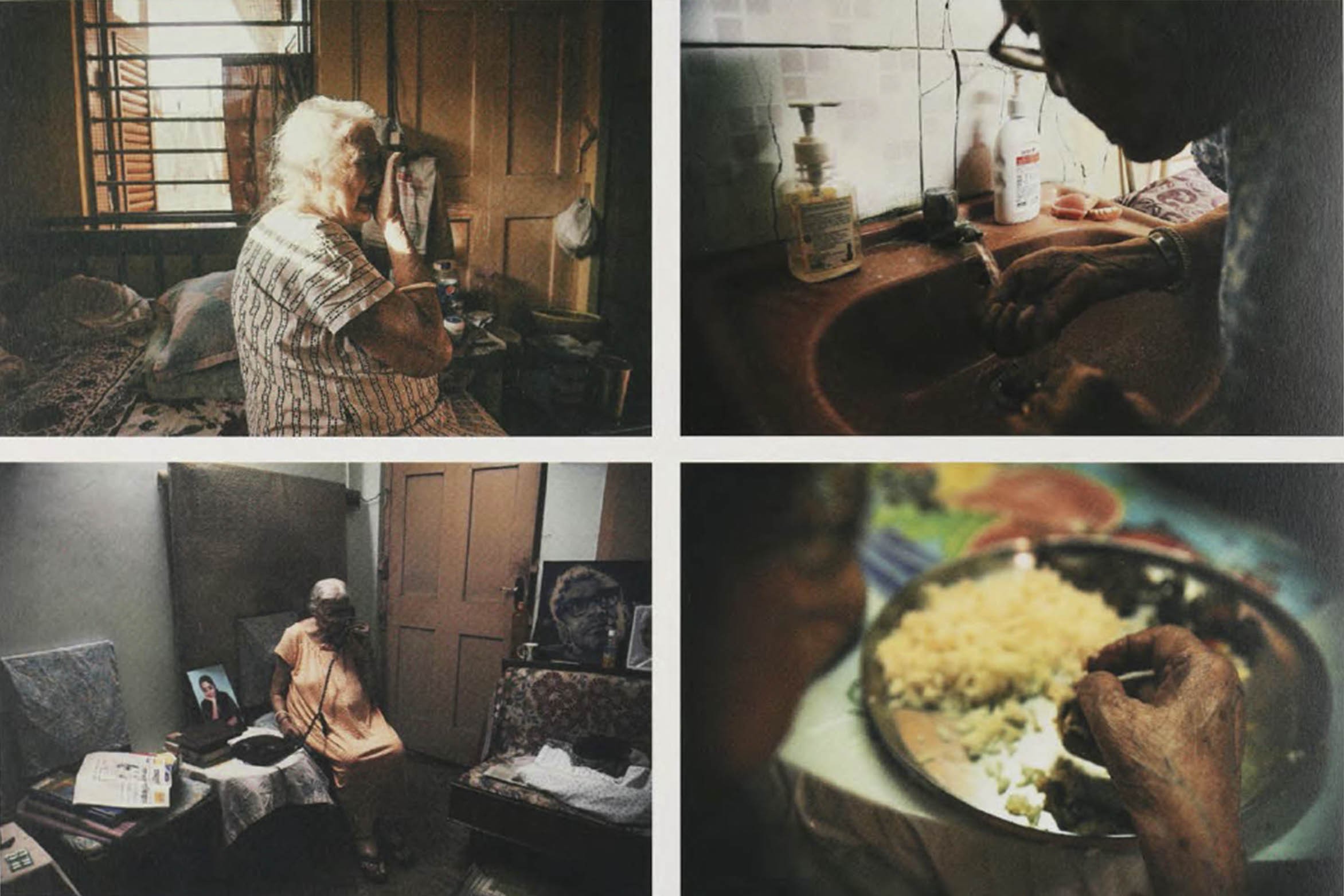

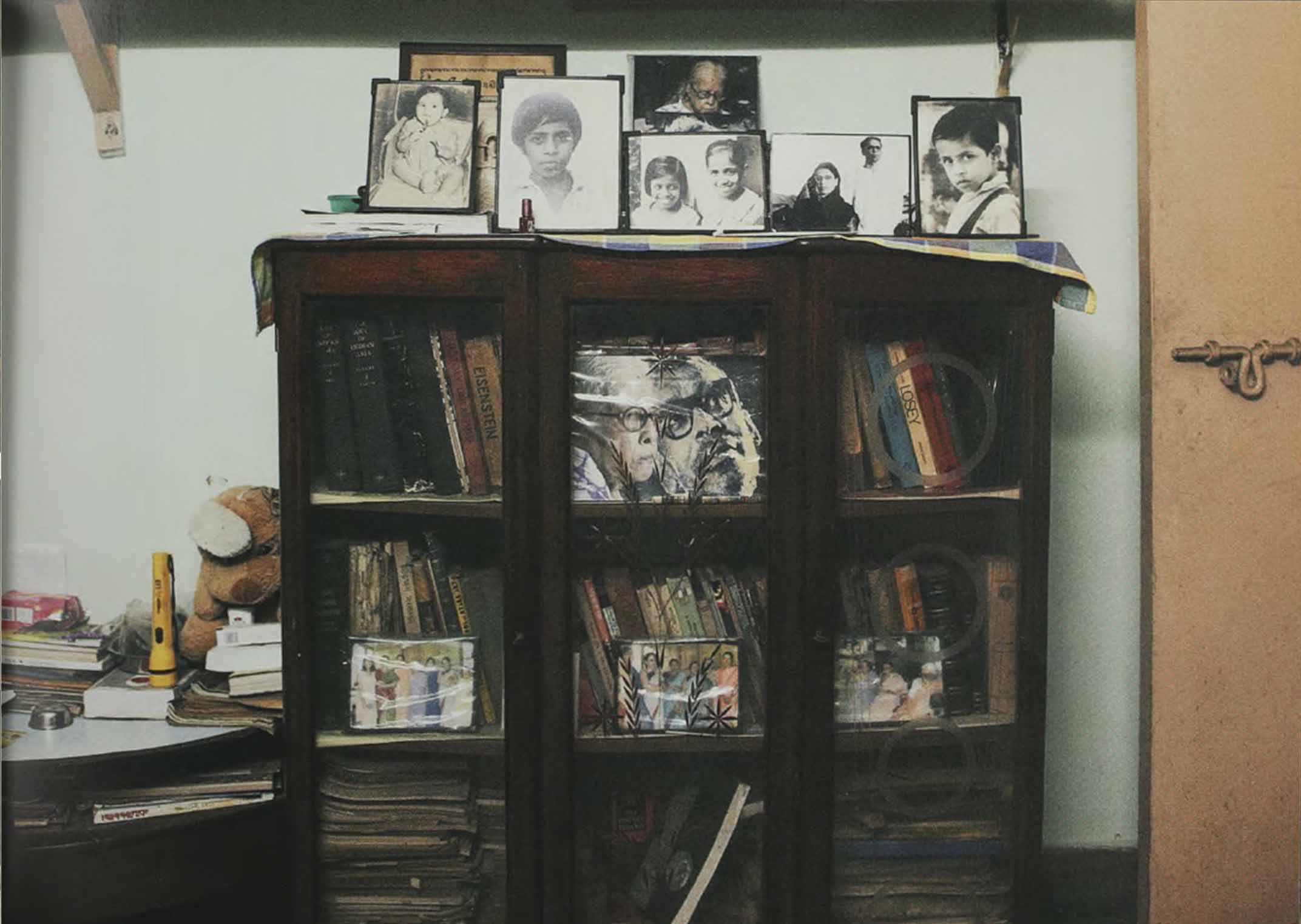

Surama Ghatak at her residence in Calcutta

Epilogue

In 1982, Surama Ghatak along with Satyajit Ray, Sankha Ghosh and Baleshwar Jha formed the Ritwik Memorial Trust. Posthumously, Ghatak received more fame and recognition, than in his lifetime.

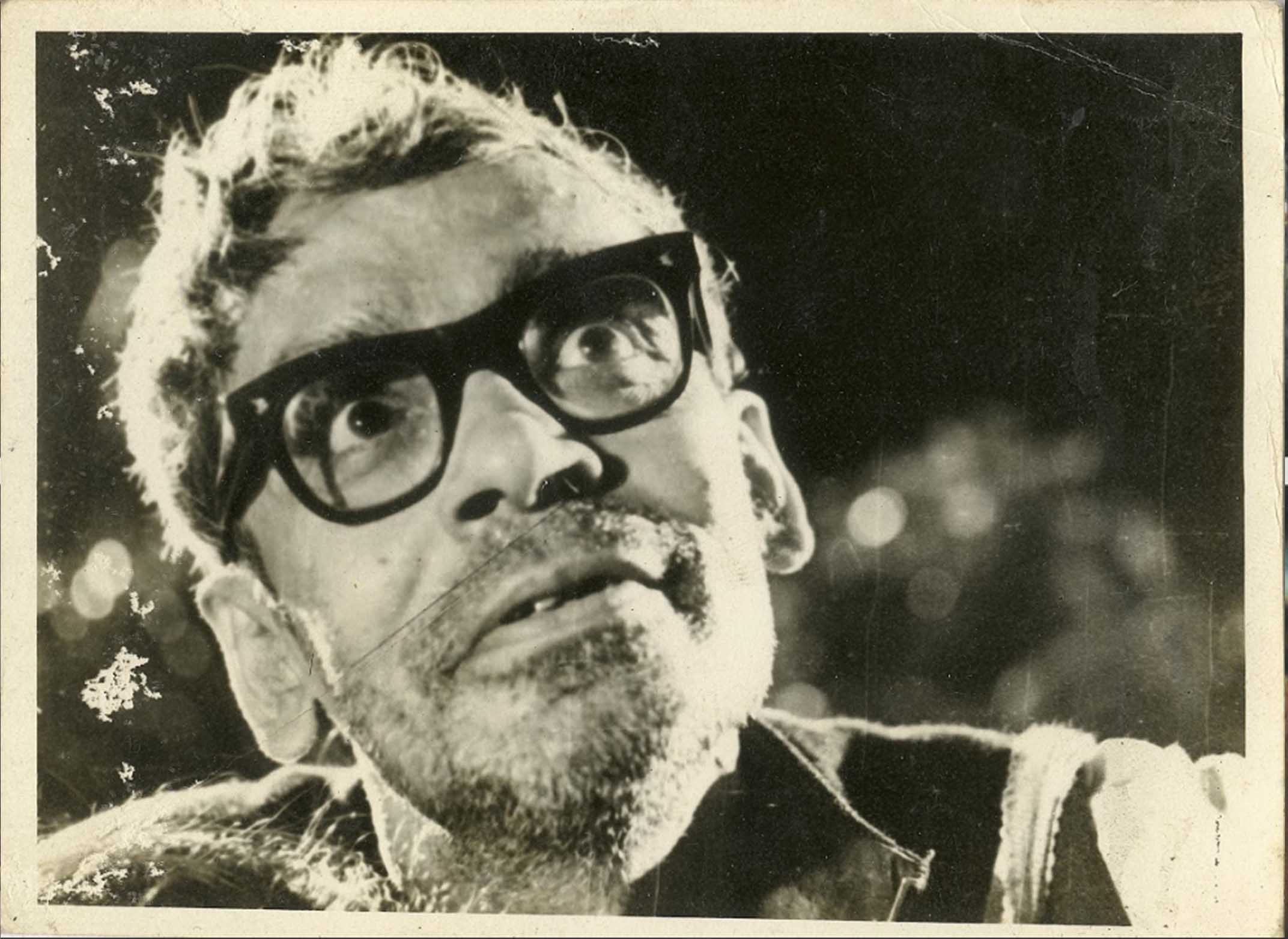

Ritwik Ghatak, 1970s

Ritwik Ghatak, 1970s

Thamma, who endured a trying and hard life, passed away at the age of ninety-two on 7 May 2018. In her last days, Thamma spent her time taking care of her husband’s letters, photographs and scripts and would sleep with Ritwik’s portrait next to her. Her memory was not very sharp but whenever I would ask her about her husband, she would smile and say that he always loved to eat and used to call her amar shona Lokkhimoni (my sweetheart Lokkhi).

After Ritwik’s death, there weren’t many who she could approach for support. She could rarely move around due to her own deteriorating health and barely received any aid from family or members of the film fraternity, all of whom, she felt, accused her of abandoning Ritwik in his time of need.

I was grateful to be by her side in her last years.

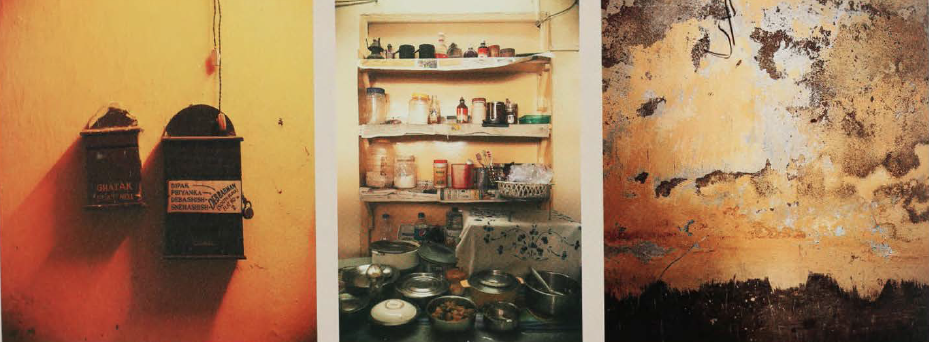

Interiors of the Ghatak residence in Calcutta, 2017

Interiors of the Ghatak residence in Calcutta, 2017

Her life has been the sole inspiration for my book, Life After Ritwik Ghatak. And it is true – I have known Ritwik only through Thamma. I believe they spent very little time together in the end but more than lovers, they were friends, both believing in the positive aspects of humanity.

For me, she is an embodiment of courage and boldness; kindness and affection; a wife and a mother, and I sometimes wonder whether she was in fact, Ritwik’s muse?

As P.C. Joshi in a letter to Surama stated, hers is ‘the silent struggle, the real life.’

The Ghatak residence in Calcutta, 2016

The Ghatak residence in Calcutta, 2016

Comments