Life after Ritwik Ghatak—Part 1

Surama Ghatak at her residence in Kolkata, 2016

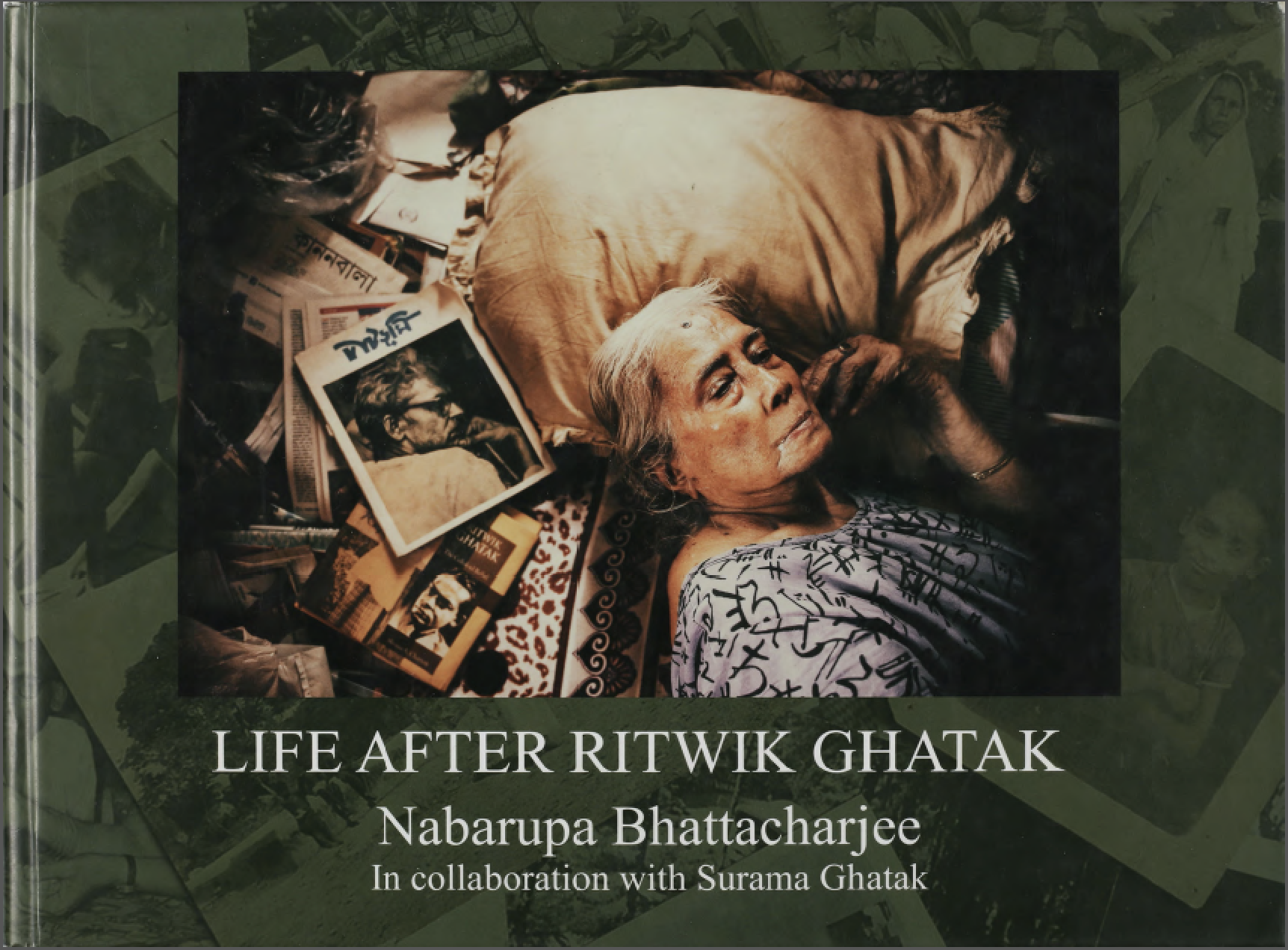

This piece, one of two posts, is dedicated to the memory of Surama Ghatak (14 November 1926 – 7 May 2018), wife of Ritwik Ghatak. Thamma as she was endearingly called is the central focus of ‘Life After Ritwik Ghatak’ (2016), a book by Nabarupa Bhattacharjee in collaboration with Surama. The project was the recipient of the Photojaanic Photobook Grant, 2016, and was released by C. Senthil Rajan at the 47th International Film Festival of India (IIFI, 2016) as a Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (Government of India) supported initiative.

In his account of Ritwik Ghatak’s place in the history of Indian cinema, film and cultural theorist, Ashish Rajadhyaksha in his acclaimed publication, Indian Cinema in the Time of Celluloid (2009), proposes that Ghatak was a pioneering and innovative filmmaker with no cinematic predecessors, having developed a unique style that combined realism, myth and melodrama. However, through the shifting terrains of bold artistic mannerisms and styles, Surama was privy to all aspects of his life, supporting and caring for him in times of great hardship. But Surama was also an activist in her own right, joining the Communist Party before they met, and even being incarcerated for two years.

Born on November 4, 1925, Ritwik Ghatak—as well as Surama—were part of a generation that witnessed devastating partitions— Bengal during Indian Independence in 1947 and the Independence of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971.

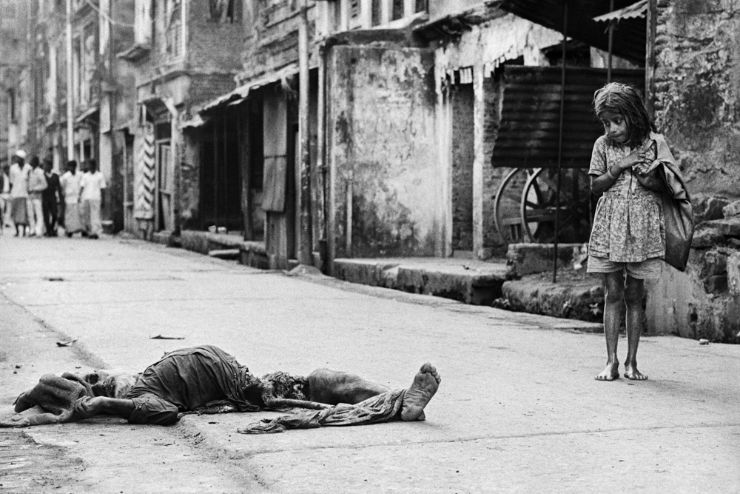

Girl gazes at dead body on the street, Bangladesh, 1971, Kishore Parekh.

Girl gazes at dead body on the street, Bangladesh, 1971, Kishore Parekh.

Source: www.talkativepictures.com/2013/03/24/kishore-parekh-bangladesh/

Through his rather short 50-year lifespan, he moved from one medium to the other—filmmaker, author, playwright and actor, trying to express the deep impact of these traumatic times, which would absorb him, both intellectually and personally. All this, with Surama striving to keep the family together, and find work in order to support Ritwik’s own ambitions.

Before immersing himself in films, however, Ghatak was part of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India, which since 1943 was a platform for politically engaged art and literature, attracting the leading artists of its time such as Prithviraj Kapoor, Balraj Sahni, Utpal Dutt, and Salil Chowdhury.

IPTA deeply influenced Ghatak’s creative outlook—he believed that the role of the artist was that of an agent for social change. He saw cinema as a form of protest, through which one could voice the anger and anguish of the refugees as well as one’s own position as a witness to their trauma. This articulation of the Partition has been profoundly captured in his trilogy – Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-capped Star), 1960; Komal Gandhar (E Flat), 1961; and Subarnarekha (The Golden Thread), 1962.

In spite of his apparent and explicit circumspection and distance from the medium, Ghatak’s experiments with filmmaking have produced some of the finest works in Indian cinema—a dizzying use of deep-focus cinematography, a carefully detailed yet often disorienting soundtrack, explorations in the epic form, immersive cinematic expression and the use of major narrative ellipses—elements that helped Ghatak tease out the vicissitudes of the human condition.

Surama Ghatak at her residence, 2016

Surama Ghatak at her residence, 2016

But outside of his films, can we view his life through the eyes of Surama? Nabarupa Bhattacharjee, grand-niece of Ghatak, narrates the story of Ritwik through an intimate lens—the memories of her grand-aunt, Surama Ghatak. Previously unseen documentation and photographs of the life they led and the one he left behind, present a view of Ghatak as a husband, a father and yet, a solitary being, compelling us to ponder Surama’s world—her own nuanced life, one of fortitude and courage. What were her own thoughts and feelings about Ritwik and their rooted yet ephemeral relationship?

Surama Ghatak next to a portrait of Ritwik Ghatak, 2016

Surama Ghatak next to a portrait of Ritwik Ghatak, 2016

Ritwik and Surama – A Life Outside Cinema

On July 24, 1971, P.C. Joshi wrote to Surama Ghatak, my grand-aunt, following a visit to the family a few weeks before then. Ritwik, by that time was ailing and alcoholic and was unable to stand up to greet his old friend. Joshi was worried and gave his friend some solace and advice to give up the addiction—but it fell on deaf ears.

Thamma, as I lovingly recall Surama Ghatak, was living in Sainthia when she received the letter from Joshi. She was working as a schoolteacher and longed for a job in Calcutta (Kolkata today) in order to support her three children and husband, though most of their acquaintances at the time assumed that they had separated. Thamma, however was not able to secure a job in Calcutta and hence stayed behind, continuing her duties as a mother of three, rather than a wife.

I have known Thamma since I was a child. She is the only woman who perplexed me to no end—how did she find herself in such a tenuous position? What were her own thoughts and feelings about Ritwik and their estranged life?

For me, Ritwik was not an outsider, and yet his life seems like a complete mystery. One might conclude that both their lives ran a tragic course, but there was more to it than loss—it was about endurance and resilience too. Through the course of my own life, having constantly questioned, doubted and engaged with notions surrounding their togetherness, I wanted to revisit my roots and understand how and from where the family began, how did Ritwik and Surama meet for instance? It seemed as though that history had been forgotten, almost without a trace.

In my collaborative book Life After Ritwik Ghatak, I have tried to arrive at some answers regarding timelines, both of family ties and professional affiliations. The idea was to retrace their lives as a married couple and develop a personal history through the images. Every foray into what remains of their archive continued to raise more questions regarding ‘how’ they lived: and the personal circumstances which had to be surmounted. There were larger considerations regarding his addiction, separation, his love and the social norms that were always transgressed: something that perhaps played out more distinctly in his films than his life; his work rather than his everyday.

Book cover, Life after Ritwik Ghatak, 2016

Book cover, Life after Ritwik Ghatak, 2016

Ritwik Ghatak, 1940s

Ritwik Ghatak, 1940s

Ritwik Ghatak or Bhoba as I knew him, was born in Rajshahi, Bangladesh on November 4, 1925. He and his twin sister, Bhobi (Prateeti Ghatak) were the youngest of nine children. Both of them were born prematurely and hence weighed less than normal. At the time, the family thought Ritwik would not make it, but as the family remembers it, the ceaseless prayers of his mother, Indubala Devi must have had some effect. His father, Suresh Chandra Ghatak, the District Magistrate was equally concerned, and perhaps some of these early predicaments or difficulties inspired his own poetic verses and plays, which are usually overlooked in the telling of Ghatak’s life.

However, unlike the rest of his siblings, growing up, Ritwik did not have a close relationship with his father. He disliked his father’s excessive drinking and vowed never to touch alcohol in his life. But there were too many extenuating circumstances. Having witnessed war and political tumult, he constantly questioned his identity, nationality and personhood but, unlike most people in Bangladesh, saw good reason in resisting norms that were imposed from the outside. The transition from India to East Pakistan and finally, Bangladesh left deep psychological scars—physical violence, state intervention, family separations if not communal unrest—all provoked a sense of rupture and up-rootedness.

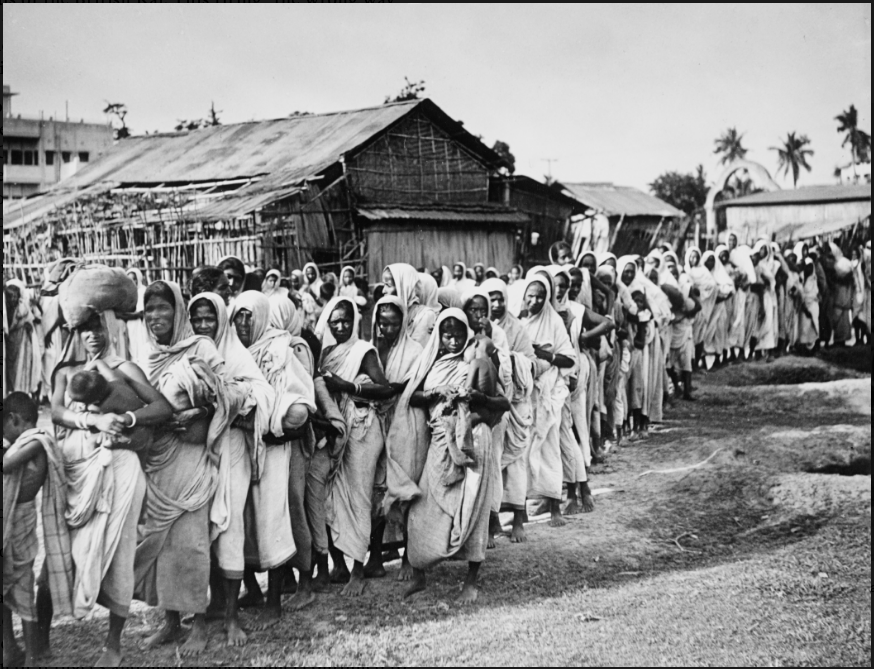

And life had already taken its toll. Ritwik came to Calcutta during the Bengal famine of 1943. He was tormented by what he saw—mothers lying dead beside their crying babies, and emaciated, starving bodies everywhere. These haunting scenes of life would later become Ritwik’s lifelong inspiration, if not compulsion for making films.

Women queuing for rice during the Bengal Famine, Lake Market, Calcutta, 1943, Sunil Janah.

Women queuing for rice during the Bengal Famine, Lake Market, Calcutta, 1943, Sunil Janah.

Source: www.documenta14.de/en/south/888_so_many_hungers

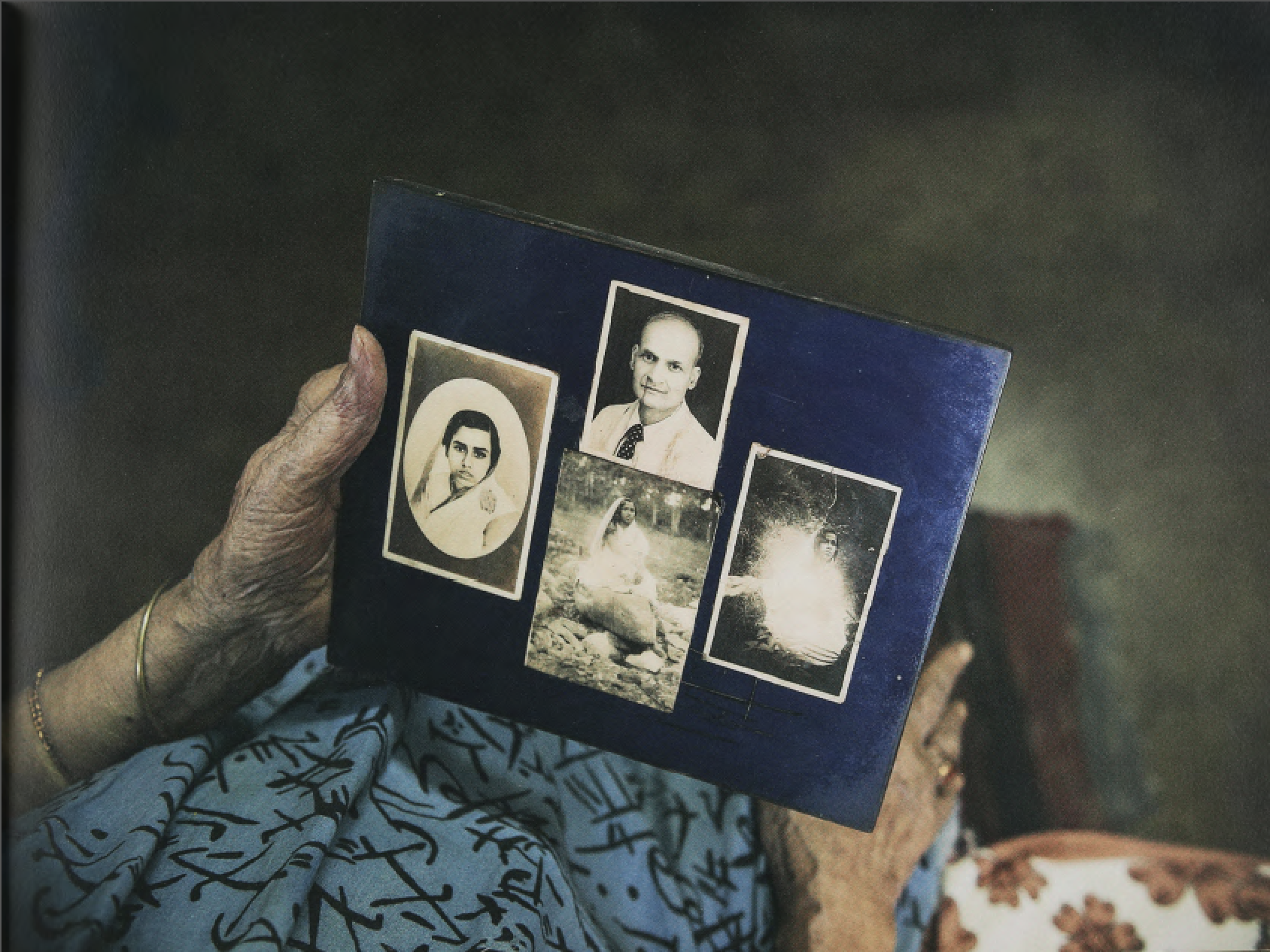

Images from the family albums, 2016

Images from the family albums, 2016

Thamma‘s life too had its own spate of tragedies. She lost her mother when she was only twelve years old. Her father, my great grandfather, Kumud Ranjan Bhattacharjee was a Banker and the Editor of the Shillong Literary Society. He brought up his daughter differently than most girls who were raised during those times. Thamma had joined the Communist Party, which went underground in 1949, the same year she was arrested. She spent two years in prison, in the company of criminals and sex workers. Thamma’s father sent her to Calcutta soon after she was released from jail in 1951—she had recently broken up with her Muslim boyfriend, and her father was worried this would cause further problems with the community at large.

Childhood photos of Surama and Ritwik

Childhood photos of Surama and Ritwik

Surama Ghatak, 1940s

Surama Ghatak, 1940s

Ritwik on the other hand, finished his degree in English literature and was an active member of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). He was popular amongst the girls whom he was tutoring in order to support his writing career. He eventually began writing scripts in the hope of venturing into filmmaking. Thamma was living with her aunt, Sadhana Roychowchury, another active left-wing member of IPTA. It was through her that Surama met Ritwik and the two immediately were drawn to one another, often meeting over coffee and fish kabiraji at the Coffee House on College Street, Calcutta.

Surama and Ritwik Ghatak at their wedding, 1955

Surama and Ritwik Ghatak at their wedding, 1955

When they married on May 8, 1955, Thamma thought they would lead an enchanted life. She was surrounded by some of the greatest intellectual minds of her time, and soon the dream of beginning anew, with a career of her own began to bloom.

Surama and Ritwik discussing films over a meal, 1960s

Surama and Ritwik discussing films over a meal, 1960s

They flew to Bombay and Ritwik started working for Filmistan Studios. But here Ritwik remained uninspired. His longing was for a different career, and his deep interests lay elsewhere, and not in the entertainment industry; rather, he was keen to pro-actively dissect social class and portray human nature under the destructive circumstances he saw while growing up—he wanted to demonstrate this somehow. He was, however, keen to set up an experimental film department at the studio, even writing to the renowned film producer, Sashadhar Mukherjee, saying “…put all sorts of hurdles before them [the mainstream industry] – low budgets, no stars, no good equipment, no fancy names of technicians, no massive sets, no legendary music directors and also no colour – just the ideas…” Despite working with films that gained commercial success, and with directors such as Bimal Roy and Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Ritwik and family eventually left Bombay, and somewhat disillusioned and returned to Calcutta.

Ritwik Ghatak, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Tapan Sinha, and Utpal Dutta had regular Sunday addas, or gatherings. It was a golden time – these young, visionary artists had nothing to lose and the world could well be seized by their political mindedness. With time on their hands, and a genuine concern for society and humanity, their intense closed-door discussions fueled their passions further. When Satyajit was shooting Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road), Ritwik’s first feature film Nagarik (Citizen), had already been completed, but due to a lack of finances, it couldn’t be released. My cousins and I were always told that if Nagarik had released before Pather Panchali, Ritwik would have had a more successful entry into the Indian cinema circle.

Nagarik poster and film-still, 1977

Nagarik poster and film-still, 1977

Satyajit and Ritwik were good friends yet they were critical of each other’s work. Mrinal Sen on the other hand, as Thamma recounts, was more of a ‘gentleman’. Satyajit and Ritwik often argued about the principle of cinema, and there were times when Ritwik became physically aggressive. This was perhaps an early indication of his mental instability, which everyone in the family, sadly overlooked.

Stills from Meghe Dhaka Tara, 1960

Stills from Meghe Dhaka Tara, 1960

After the release of Meghe Dhaka Tara in 1960, Ritwik gained enormous recognition. But this also was the last happy year for the couple.

The next year Komal Gandhar released. It was a commercial failure, and Ritwik was devastated. Thamma was doing her Masters at Jadavpur University, but she dropped out due to his depression. Thamma had no inkling that Ritwik had started drinking heavily until one day she found him in complete stupor, almost loosing control of his physical functions.

By this time, conjugal life between the couple had deteriorated completely. However, Thamma still remained a supportive wife, but she was saddened that she could not complete her education. She never let go of the dream of being independent, and striving for her beliefs. She knew that her husband was depressed due to his profession and all she could do was stand by his side. This was a difficult time marked by regular conflict and immense financial insecurity; and very soon, they started living apart. Thamma thought that if she secured a job, their day-to-day concerns would disappear. She could deal with the household expenses and Ritwik could concentrate on his work without worrying about paying the bills.

Unfortunately, Thamma had to withstand another shock. When she broached the topic of looking for a job and moving back together, Ritwik informed her that he had fallen in love with a woman named Meera Janna and wanted to start a new life with her. Initially devastated, Thamma vowed to dry her tears and move on. Their relationship would never be the same again.

Surama Ghatak, 2016

Surama Ghatak, 2016

(To be continued)

Comments