My Afghan Photo Album

A TV camerawoman vying for a spot among male colleagues to cover the Nowruz celebration, Kabul, 2014

The news comes in waves. The Taliban have completed their takeover of Afghanistan.

Flabbergasted by the sheer speed of this re-capture, I dig into my old photo albums with images I have been taking in the country from 2002, since the last US invasion. I wanted to remember the faces of the people who have been at the receiving end of some of the worst atrocities imaginable – a land violated again and again by world powers over centuries.

I looked at a photograph of a wide-eyed, bright faced girl in primary school, located in the small town of Charikar, just north of Kabul. I recall how, with a sparkle in her eye, she proclaimed, ‘I want to be a policewoman when I grow up.’ That image was taken seven years ago. She must be a teenager now, possibly going to high school. I wonder if she still wants to be a policewoman or if she has different goals. Becoming a policewoman is now virtually out of the question for her. The dire situation is such that she may not even be able to attend school given the Taliban’s well-known practice of disallowing education to grown-up girls and women, and how at present, women teachers and students in certain parts have been asked to stay home.

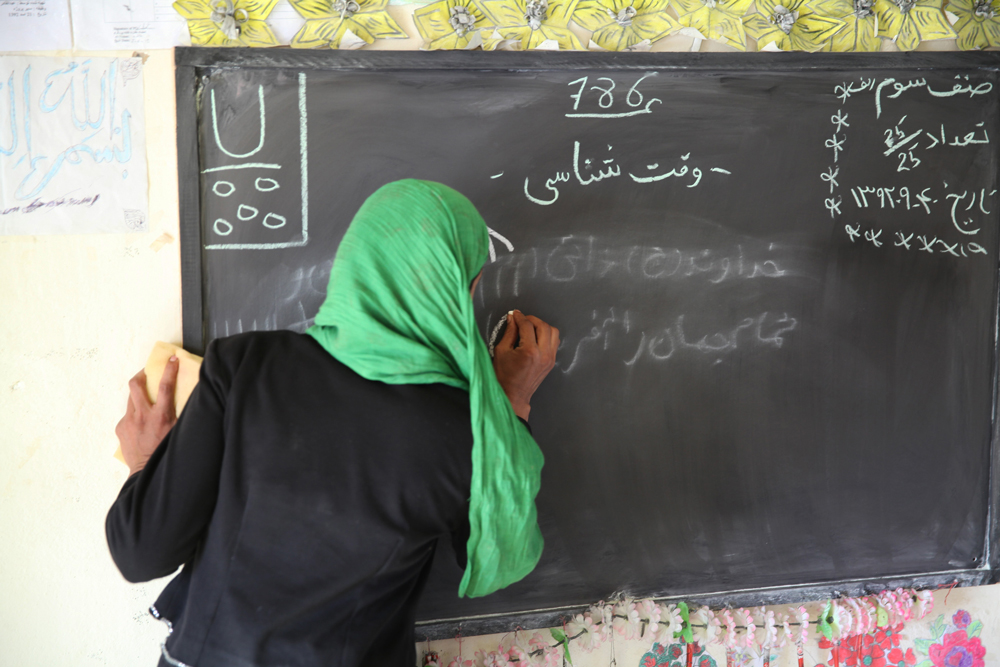

Classroom in a Girls’ School. Charikar, 2014

Classroom in a Girls’ School. Charikar, 2014

I come across another group of images of young and middle-aged women sitting on a carpet. The walls are adorned posters scripted in Dari, announcing the rights of women and a campaign against domestic violence. When I took the photograph, though the women are draped in burqa and chador, I recall how they clearly expressed their opinions. I did not completely understand what they were discussing at the time, barring the smattering of a few familiar words. However, the energy and conviction with which they were conversing was palpable, and the message clear.

My photos then took me to the celebration of Nowruz in 2014 – the Persian New Year near Hazrat Ali mosque in the Shia quarters of Kabul. Parents accompanied their children in their best attires and presented them proudly to the camera as I approached them asking for permission. I remember how the toddlers ran around excitedly taking turns on a wobbly merry-go-round. Their joy knew no bounds. I also took a photograph of a camerawoman working for a local TV channel vying for a vantage point among several other cameramen, perched atop a building overlooking the mosque complex.

Travelling through the country for almost 15 years while working for the BBC as a Field Producer and later as a Senior Editor, I was interested in the lives of ordinary Afghans, going beyond the oft repeated ‘Afghanistan-at-war’ visual narratives that had dominated the media. I wanted to understand the indomitable ‘Afghan spirit’, unwavering in their resolve and resilience, some images of which were published in the catalogue of Kabuliwala, a project jointly realised with Moska Najib, based on Rabindranath Tagore’s iconic short story. But I also wanted to know how they spent their leisure hours and had other pursuits – if they had meals as a family outside their homes; if they went to art exhibitions; what their weddings were like; how important it was to send their kids to schools. I wanted to see how women took part in public life, their public engagements.

At Nowruz celebrations, Kabul, 2014

At Nowruz celebrations, Kabul, 2014

There are now more layers to these narratives, bound to emerge through the perspective of the present paradigm shift. I am reminded now of other images…

The face of a lone woman amidst rows of turban-clad sombre faced bulky men at a local Jirga or assembly in 2002, in which the country’s future was being discussed. As I progress through these years in photographs – a filmic reel of exchanges and captured events – I recollect how girls and boys were in classrooms, some housed in makeshift tents in 2002 while others in colourful and bright school buildings in 2014; I see tens of thousands of young men and women attending universities, and several other moments which were conceivably going to set the country on another, more liberal path. I see women in public space; I see more women taking part in politics and government.

I am also aware that at this moment, publishing many of these images will not be possible. As long as the Taliban are in power, such images may well become difficult to share publicly. At the same time, they could also become part of an archive that will reclaim and revive the lives of those that survive persecution. And though redacted images often lose their souls, the affective nature of photographs have the potential for filling in gaps over time, and can, in the future, help counter the oppressiveness of the current regime.

Kids make an orderly line to enter their class room, Herat, 2013

Kids make an orderly line to enter their class room, Herat, 2013

I am also reminded of the photography book by the British photographer Harriet Logan, Unveiled: Voices of Women in Afghanistan, which charted the journey of women in the country from 1970 to the times of the Taliban between 1996 to 2001.

One of the overtly publicised archival images – of three young women in short skirts, high heels, walking in the streets of Kabul confidently, depicting a different Afghanistan of the 1970s, has been re-circulated on social media over the years, and even underscored for a certain stereotyping. Though I had seen this photo for the first time on the back cover of Logan’s book, she also used other images – women taking part in student politics at the university for instance. Logan‘s book additionally presents haunting images, supplementing the ones she took from 1997 at the peak of the Taliban rule, until 2001. Given the immense time lag between 1972, when those three women could walk the streets of Kabul, to 2001-2002, when all you see is women covered in burqas, we can observe how women’s attire changed with successive regimes, indicative of prevalent ideological and/or social restrictions. Afghan women have constantly navigated these impositions, and I wonder now about the repeating arc of history, and how the actual lives of many of her subjects were spent.

In 1972, Afghanistan was a conservative Muslim country but the beliefs did not sanction the extreme violence we have subsequently witnessed. Throughout the 1980s to the early 1990s, women enjoyed relative freedom during communist rule in the country. So how and why were they rendered invisible from 1996 onwards?

This question becomes central to unpicking everything that has happened in Afghanistan from the 1970s to the civil war years, until the Taliban rule between 1979 and 2001 – and now the hostile takeover of the Taliban in the past one week. Some of the most orthodox interpreters of Islam – the Wahibis and the Salafis – were facilitated by the Western powers following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the winters of 1979. Afghans did not create the international jihad, neither did they have any history of being part of political Islam – it was created as part of the ‘cold war’ to counter the USSR and imported into the country.

The high degree of conservatism we see today, arose for other reasons altogether. After the politicised version of Islam was implanted in the 1980s following the Soviet invasion, tribal conservatism and Sharia overlapped. The fiercely independent Afghan tribes wanted to remain in seclusion—at a safe distance from outside influence. This so-called ‘forbidden country’ with a most picturesque landscape, at once a mythical destination that lured Western explorers in the nineteenth century to expand spheres of their political influence eventually led two European powers, Imperial Britain and Tsarist Russia, to interfere in Afghanistan’s internal matters.

This race for Central Asia – the ‘Great Game’ – as coined by Rudyard Kipling in his novel Kim (1901), has been continuing since, and has been captured subsequently by the media with images of warlords, endless invasion, youth indoctrination, religious intensification, communist sway and propaganda. Some dimensions have also been highlighted in Pakistani journalist Ahmad Rashid’s book, Taliban: The Story of Afghan Warlords (2001), if not in the one-sided, dramatised depiction of the Hollywood film Charlie Wilson’s War (2007). We may well ask what the legacy of these representations come to mean in the present moment. At the same time, we must acknowledge how the Taliban is the disastrous outcome of the West’s skewed foreign policy to thwart communism, causing so many ordinary Afghan’s to suffer for so very long.

What we do see is how, after fulfilling their goal of ‘defeating’ communism and the USSR, the West turned its back on Afghanistan in the early 1990s, leaving it in chaos.

The same is happening today.

Going through my dispersed album of images, it is also evident how the past twenty years has been a time of hope for young Afghans. They were connected with the world like never before. Their skills and imagination in media, art, governance and business can be seen in these images. They were taking charge of their country, a moment that now seems to be in jeopardy.

We may now ask ourselves as viewers, documentarians, history writers, or just as a people – when is the time to revive or remember vital narratives that are elided by oppression? I can see in the image archive for instance, how women artists have produced graffiti on the walls of Kabul to raise social consciousness, how networks/collaborations of film and photography collectives and organisations have paved the way for more inclusivity in the region, how international festivals like Documenta have been realised in public space, and how the streets were once the place of congregation and respect.

This is also the Afghanistan I remember.

The tomb of Rabia Balkhi, the Princess of Balkh and Afghanistan’s first known woman Sufi poet from the 10th century, 2012

The tomb of Rabia Balkhi, the Princess of Balkh and Afghanistan’s first known woman Sufi poet from the 10th century, 2012

ALL IMAGES BY AUTHOR

Author

Nazes Afroz has worked as a journalist for more than 40 years, 18 of which for the BBC, covering current affairs spanning South, Central and West Asia in the capacity of a producer and later as a senior editor. His work has taken him to Afghanistan regularly since 2002. Apart from coauthoring a cultural guidebook on Afghanistan, Nazes has translated Bengali scholar Syed Mujtaba Ali’s classic memoir of his time in Kabul, ‘Deshe Bideshe’ into English under the title ‘In a Land Far from Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan’. As a passionate documentary photographer Nazes has held several exhibitions in countries across three continents from 2015.

Comments