Re-creating Pastness

View of Light Works exhibition. 2017. Jitendra Arya Foundation

“While the scene stills and on-the-set candid shots would be used to sell the movie, the portraits could be used to introduce a would-be star to an international audience.” —Maxine Ducey, Hollywood Glamour, 1924-1956: Selected Portraits from the Wisconsin Center (1987, Madison, Wisconsin: Elvehjem Museum of Art)

It was Jitendra Arya’s ability to ‘create’ a star by deploying the craftsmanship of a very refined visual artist, which defined his impeccable and convivial style as a cinema photographer.

Jitendra Arya is well known today for his formal portraiture and stylised studio lighting, which is resonant of renowned practitioners such as the Armenian-Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh’s dexterous, if not subtle use of light, shade and shadow. Additionally, Jitendra had the unique ability to enter a more informal space, his subjects visibly at ease, in order to frame a moment through candid images – a personal treatment which remains a largely unacknowledged part of his oeuvre. It is this compounded versatility that Light Works, a retrospective of Jitendra Arya, presented at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai in 2017 explores, by revisiting the archive, managed now by his next of kin.

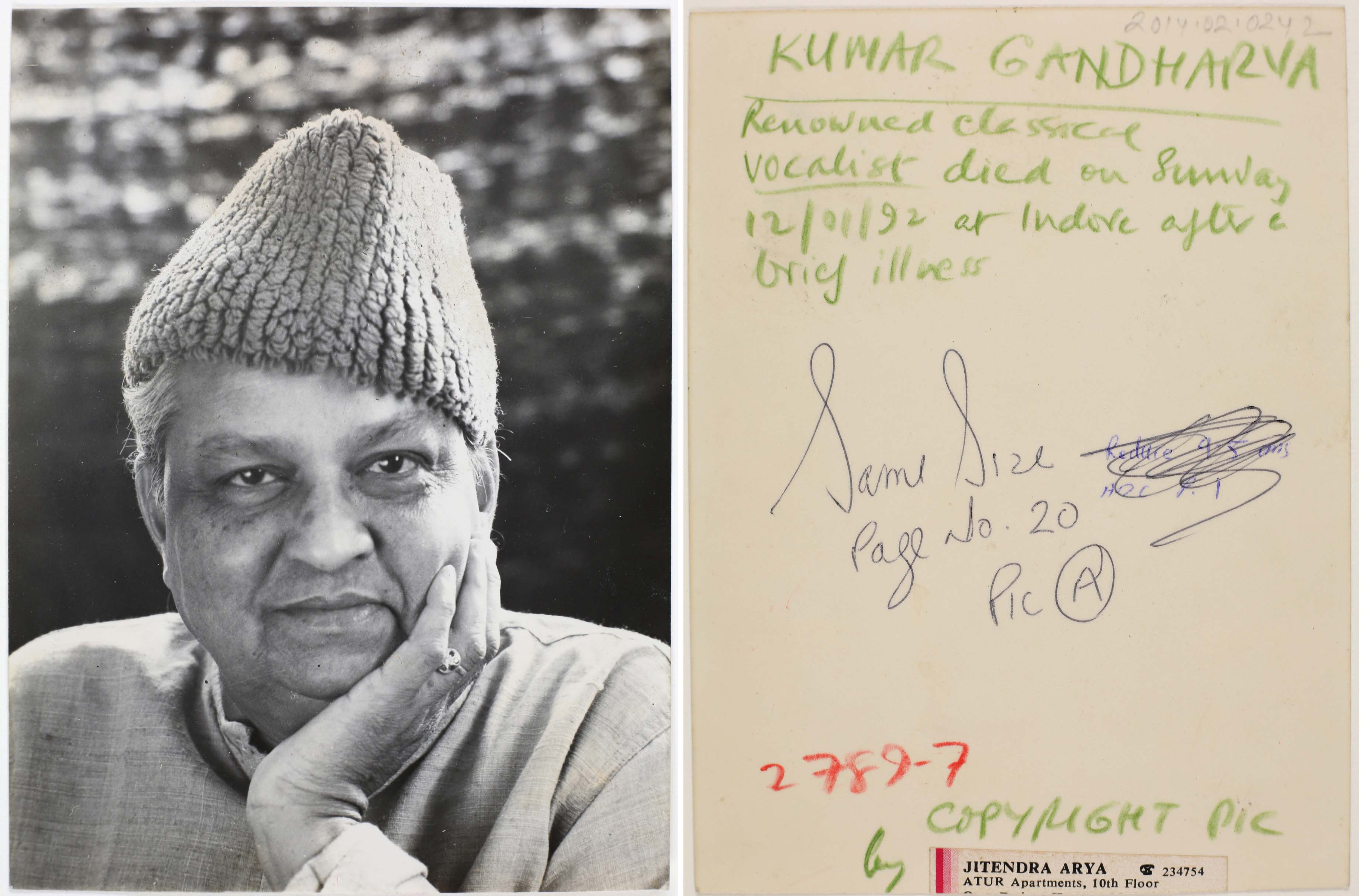

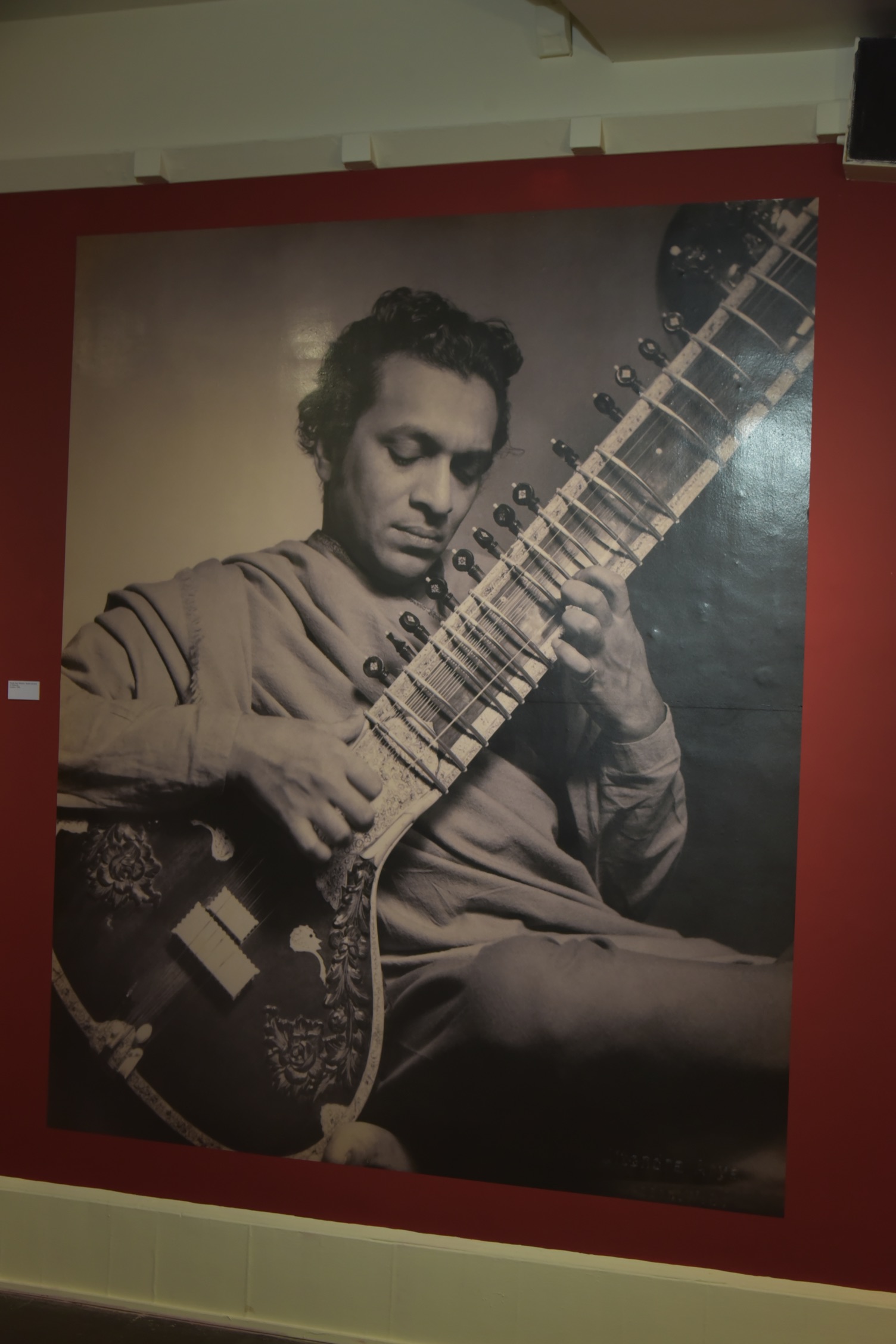

Jitendra Arya, Kumar Gandharva, 1980s–90s, 158 x 66mm, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Jitendra Arya, Kumar Gandharva, 1980s–90s, 158 x 66mm, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

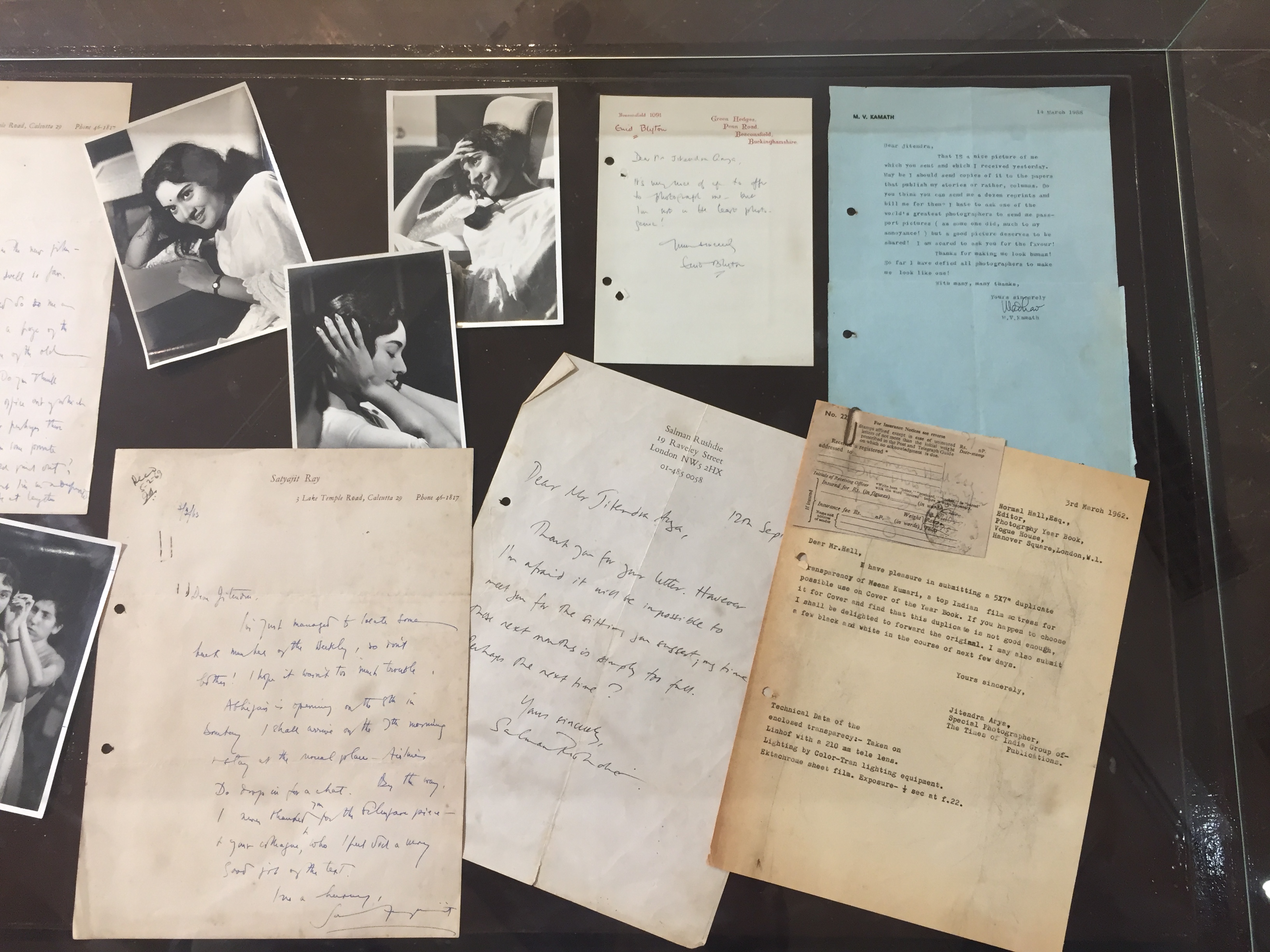

Display at Light Works exhibition, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Display at Light Works exhibition, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

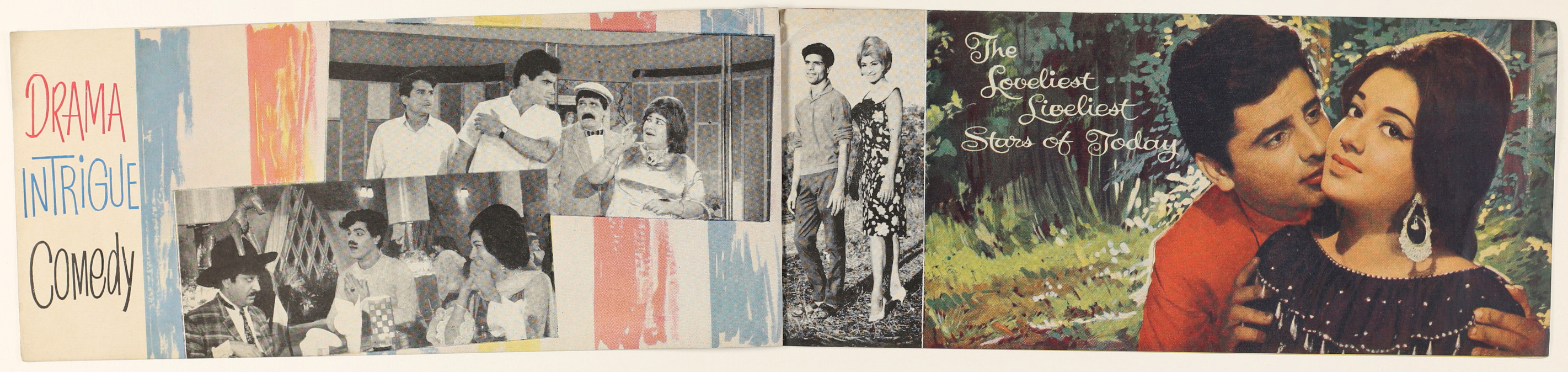

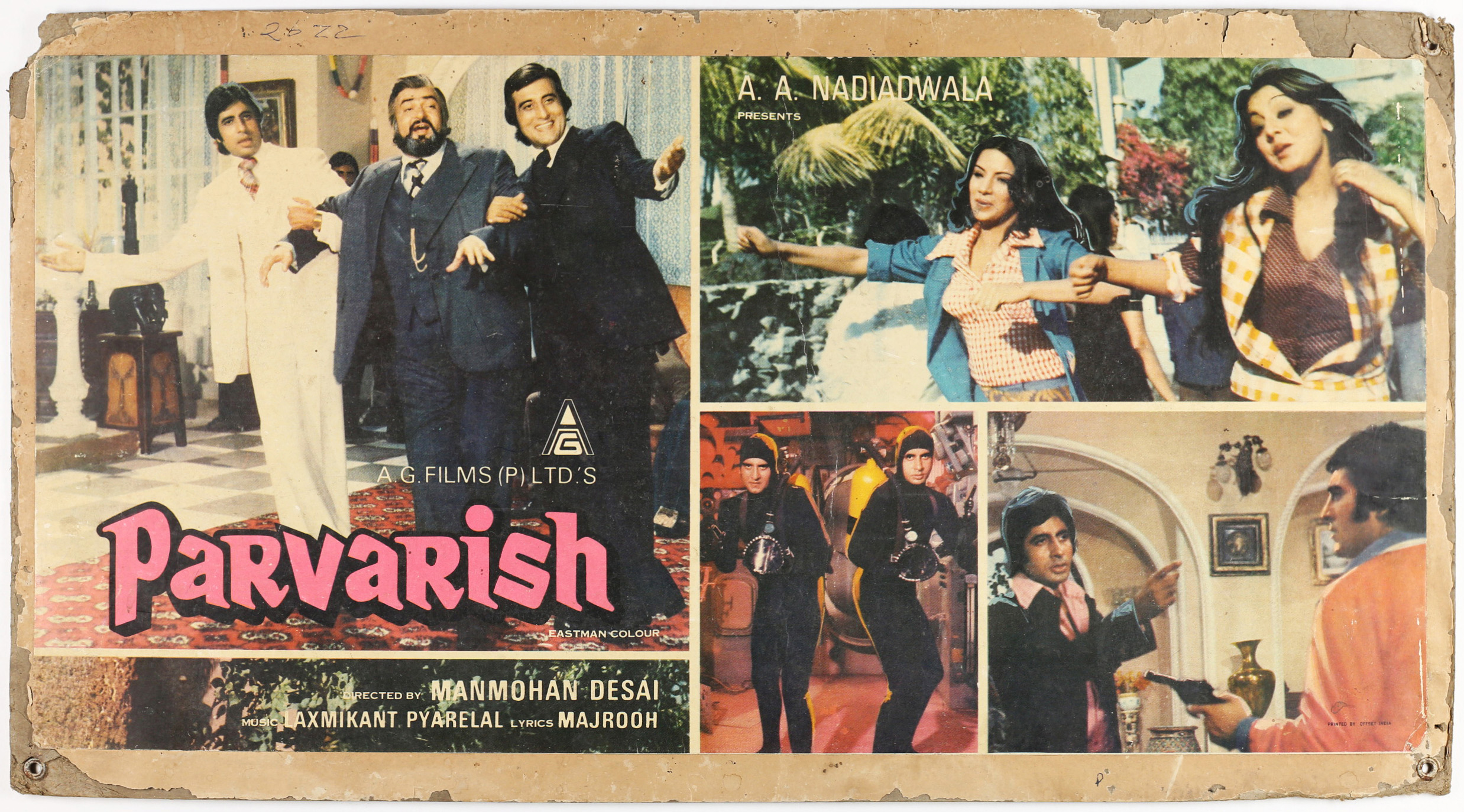

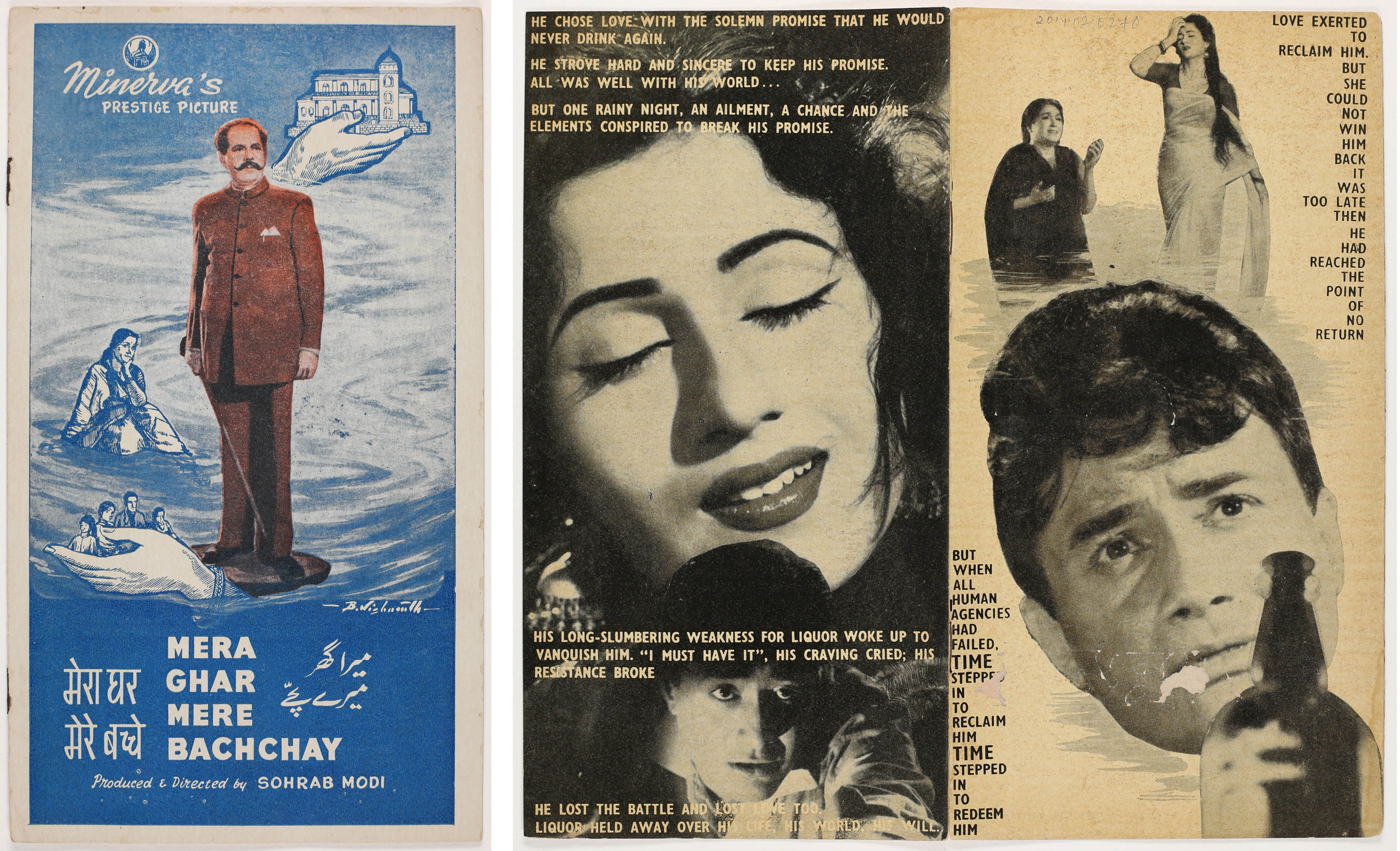

Photographic promotional material of and around films, mostly by anonymous practitioners through the 50s, up until the 90s, often combined painterly renditions through filters, lithographic printing or even halftone printing. The images that finally appeared for publicity purposes—surreal and hyper-real compositions when colour photography was unaffordable, suggest that there is an entire history of print culture that remains unexplored.

Songbook for the movie Dus Lakh, 1966, 121x 285mm, Editors’ Collection.

Songbook for the movie Dus Lakh, 1966, 121x 285mm, Editors’ Collection.

Lobby card for the movie Parvarish, 1977, 314 x 577mm, Editors’ Collection.

Lobby card for the movie Parvarish, 1977, 314 x 577mm, Editors’ Collection.

(Left to right) Songbook of the movie Sharabi, 1964. 264 x 139mm (closed); Songbook of the movie Mere Ghar Mere Bachche, 1960, 223 x 127mm (closed).Editors’ Collection.

(Left to right) Songbook of the movie Sharabi, 1964. 264 x 139mm (closed); Songbook of the movie Mere Ghar Mere Bachche, 1960, 223 x 127mm (closed).Editors’ Collection.

In this context too, Arya’s contribution to the image culture of Indian cinema, presents a refined, formal aesthetic that elevated commercial photography to a structured and respected profession for time to come. His contribution as a magazine editor in the 60s, was to achieve standards of printing that would give the photographs the effect and quality they so warranted.

Even as early as the 1920s, studios in Hollywood such as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer recognised the transformative quality of photography. Portrait photography became one of the key elements in amplifying the image of the performer and henceforth turning performers into ‘stars’.

(Left to right) George Hurrell, Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer, Joan Crawford, 1936, Creative Commons; Photographer unknown, From the movie Dil, 1946, 294 x 238mm; Photographer unknown, Meena Kumari, 1950s, 129 x 81 mm, Editors’ Collection.

Until the 1950s, when the field grew exponentially, photographers like George Hurrell, Clarence Sinclair Bull and Ruth Harriet Louise developed a style of Hollywood portraiture, turning the subjects of these images into icons of the silver screen.

In India, photographers like James Burke who met an untimely demise in Assam in 1964, travelled here to shoot Begum Para, who starred in films like Neel Kamal (1947), and Jharna (1948), for LIFE magazine, presenting her as symbol of glamour and sensuality.

(Left to right) James Burke, Begum Para, 1951, Creative Commons; Photographer unknown, Nanda, 1970s, 302 x 238mm, Editors’ Collection.

Outside the domain of portrait photographs, the presence of such interactions and emerging modern perspectives—the Indian subject and the Western aesthetic cannot be undermined. Most recently, an exhibition titled, A Cinematic Imagination at Serendipity Arts Festival, Goa, 2017 showcased, for the first time, images by Josef Wirsching, German cinematographer and Director of Photography of the Bombay Talkies. These behind-the-scenes images, portray a dramatic German expressionist aesthetic, which brought to Indian cinema a certain universalism in the pre- and post- Independence years and may well have served as a resource for future photographers of the Indian cinema.

But how do you bring alive images which speak of a different time, especially in post-independence India? In digitising his archive, what decisions would Arya have taken? How did he re-define stardom?

Below, Sabeena Gadihoke, Curator of Light Works, shares her insights.

Some months ago, I curated a retrospective of celebrated portraitist and commercial photographer Jitendra Arya titled Light Works at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai. Arya’s career that spanned over five decades began in Kenya and London and after which he relocated to Bombay in 1959. Since most of his photographs were published in magazines, they have disintegrated over time and many of them are lost.

Besides some originals, the show was constructed through a return to Arya’s negatives. The process of digitisation came with the realisation that the full expanse of his work is yet to be discovered. While formal portraiture was indeed Arya’s forte, his ability to capture the fleeting moment through candid photography was no less remarkable. The exhibition displayed Arya’s production stills on the sets and locations of several films in Hollywood and Bombay. He was also an early architect of fashion photography.

Ravi Shankar at Jitendra Arya’s studio in London taken in late 1950s at the exhibition, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

One of the major sections in the show focused on stardom. Known as the ‘Yousuf Karsh of India’, Jitendra Arya launched the careers of many aspiring actors who went onto become famous. A number of film stars were photographed by him during different stages of their lives and career. Here is a photograph of ninety-year-old Kamini Kaushal in front of a cluster of photographs at the show. Two of her own images that appear on the wall behind were taken by Jitendra Arya during the 1950s and 1980s. This group of pictures included not just those who appeared on the screen (like Kaushal) but others who were stars because of their amazing voices such as Lata Mangeshkar, Noorjehan, Mallika Pukhraj, Runa Laila and Nazia Hasan who tragically died young.

Actor Kamini Kaushal on a visit to Light Works, The portrait of Mala Sinha can be seen the background, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Actor Kamini Kaushal on a visit to Light Works, The portrait of Mala Sinha can be seen the background, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

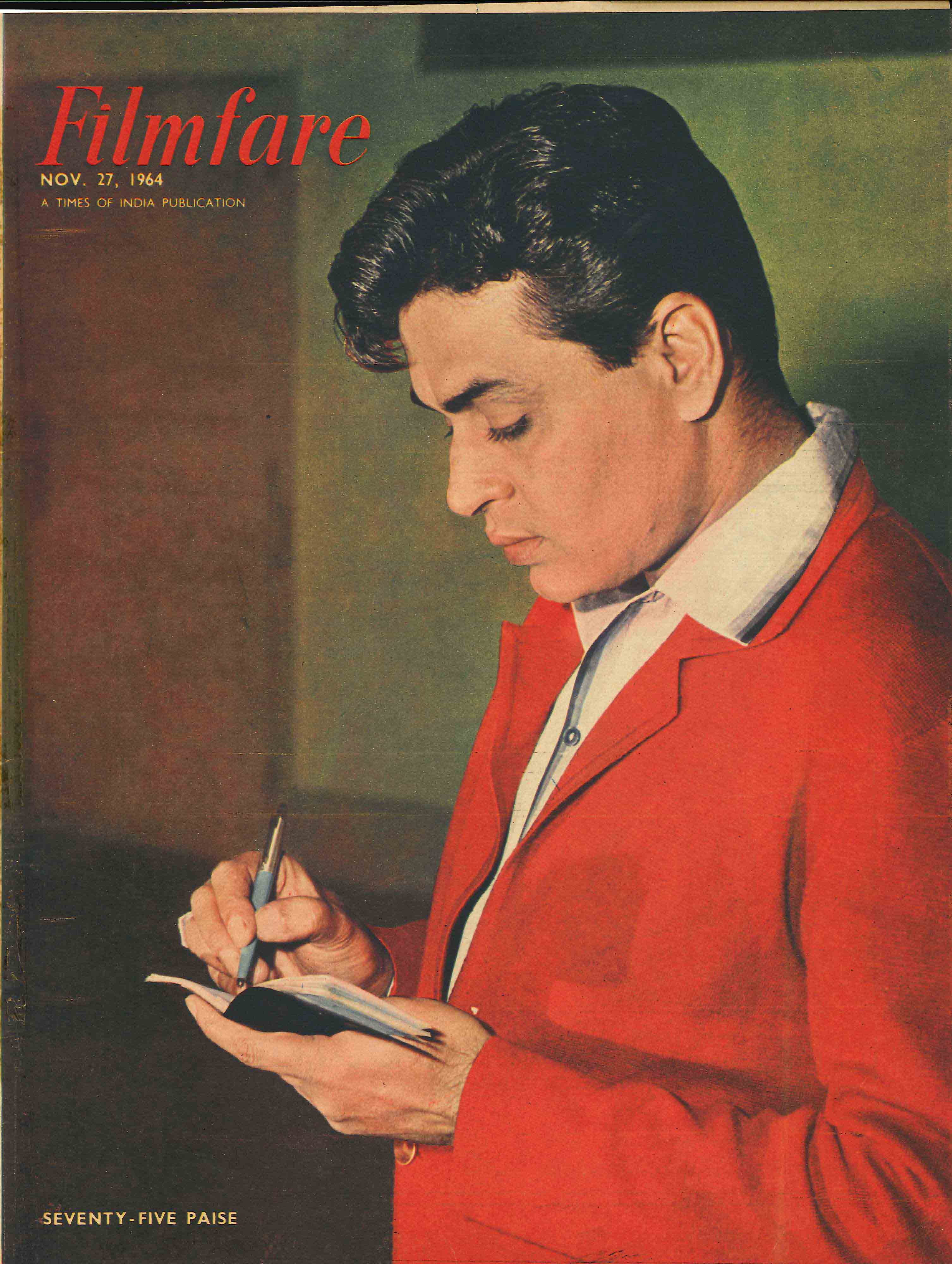

A master portraitist, Arya had the ability to infuse most of his subjects-famous and otherwise with an aura. Arya once remarked that celebrity images had raised the bar of photographic reproduction as glamour demanded higher production values. When in the 1960s Jitendra Arya started his career in India, most professional photographers sought to publish their works in illustrated magazines even though the available print technology resulted in a majority of the images looking grainy and indistinct. Arya struggled to achieve a standard of reproduction that would do justice to the representation of stars and his own craft as a professional.

Jitendra Arya, Rajendra Kumar, 1964, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Jitendra Arya, Rajendra Kumar, 1964, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

His original black-and-white prints had beautiful tones. From the late 1950s he was experimenting with different kinds of 35 mm colour film and from the 1960s he was making Chromogenic or C prints that were popular till digital prints arrived. He also made prints from Positive or slide film (Ektachrome and Kodachrome) and hand coloured some of his negatives too. Light Works used many of his original monochrome and C prints but for a large part we digitally re-printed some negatives.

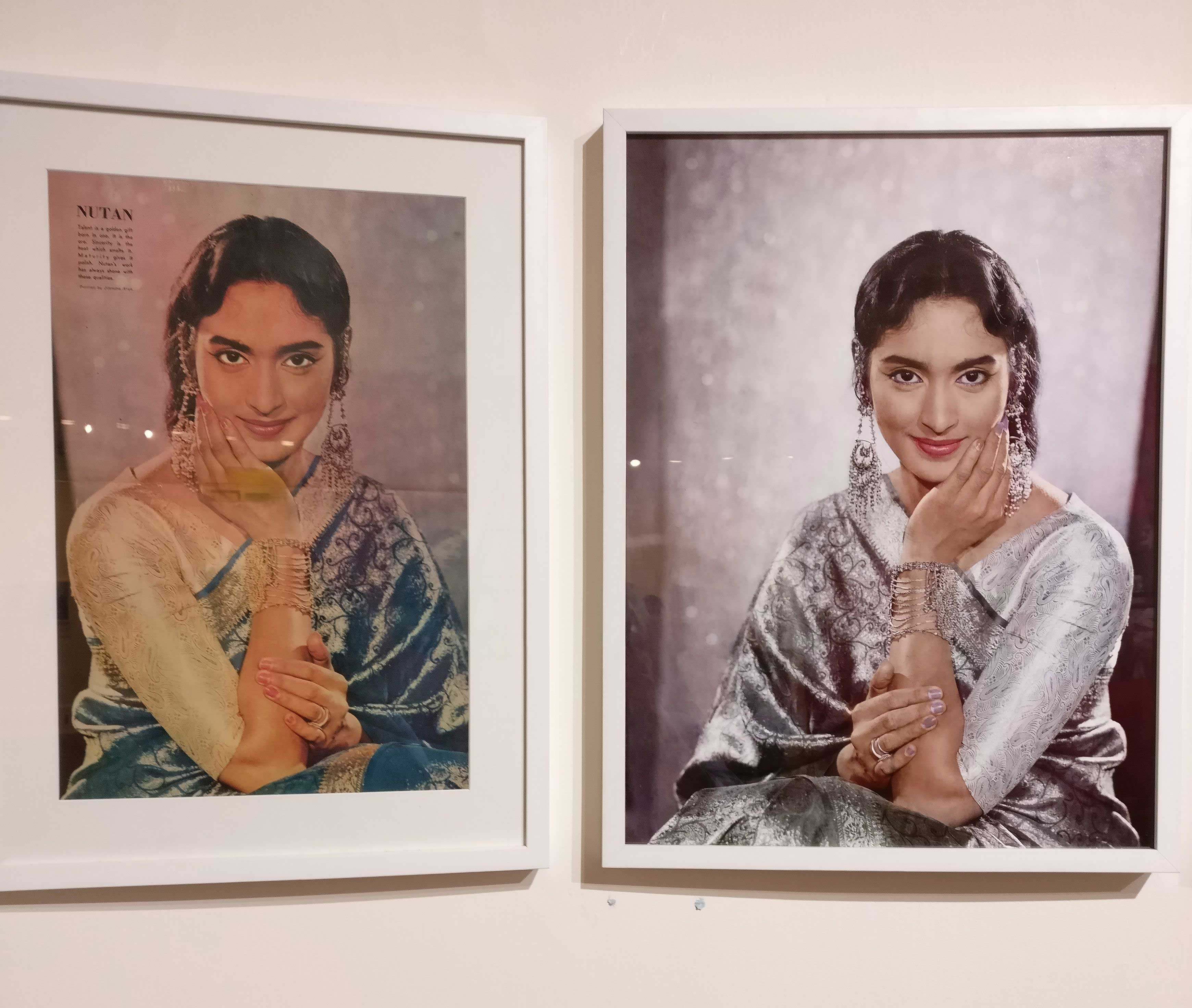

As a professional Arya’s black-and-white exposures were near perfect and besides cleaning them, one only needed to check the tonality of the skin tones while scanning. Colour however proved to be much more complicated. There is an arresting portrait of Mala Sinha behind Kamini Kaushal who was her colleague in the industry from the 1950s. Sinha wears an olive green sari with a purple blouse, but while restoring this image, one noticed that her lipstick and her bindi had a tinge of purple too. While this was not completely ‘realistic’, it was retained as the hue added to the glamour of the picture. Of course there was a more practical reason for the shift in colour in these negatives that were almost half a century old.

The original pink negative and a version created by the lab, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

The original pink negative and a version created by the lab, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Chromogenic prints used a photographic paper that contained three emulsion layers, each of which was sensitised to a different primary colour. It was then submerged in a chemical bath to create a full colour image. The nature of the process made the print very sensitive to light and humidity and therefore C prints deteriorated much faster. Moreover, unlike black-and-white that became a rich sepia (and still have some kind of referent to the ‘original’) old colour negatives are known to turn pink. Over time the cyan and yellow layers of the negative fade, leaving only the magenta. The lab scanning Arya’s colour negatives was working on hunches while restoring them.

References wherever possible were not helpful as colour reproduction in magazines was not always up to the mark. Neither were skin tones (like in the case of the black-and-white images) because pancake make-up or foundation in the early days of colour was not exactly ‘realistic.’ Given these handicaps, the lab picked a mid range grey in different parts of the faded negative to re-imagine what these images from the past might look like. They ‘painted’ the image with Photoshop in much the same way as Arya may have done by hand many years ago. This resulted in some unintended but welcome ‘mishaps’ too. For instance we printed up another pink negative as a beautiful portrait of the actress Nutan wearing a silver sari and jewellery. A few days before the opening, we found the original image printed in the magazine Filmfare, where Nutan wore a turquoise sari and golden jewellery! Both images found their way to the gallery eventually and placed side by side, they drew attention to the process of reconstructing images for the show.

The original and the re imagined image of Nutan in the gallery, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Another deliberate intervention was to remove the colour and reverse the direction of a well-known portrait of Meena Kumari made by Arya on the sets of Pakeezah (Kamal Amrohi, 1971) in the 1960s. Placed on one of the main panels of the show, the reversal allowed Jitendra Arya with his Linhof camera to ‘face’ the subject that he immortalised.

Jitendra Arya with the reversed Meena Kumari. Picture on display at the site of the exhibition, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Digital reconstruction involves many material decisions too. In attempting to be as close to Arya’s original images, the prints from the original negatives were made on a Harmon gloss Baryta paper. As an employee of Bennett Coleman and company limited (the Times of India), Arya had shot thousands of covers for magazines like Femina and Filmfare. We chose to draw attention to this history of print culture by colour xeroxing them. These much brighter ‘copies’ of the older covers were used to create a huge collage on the wall.

The wall of colour xeroxed magazines at the exhibition, 2017, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Of course, newness’ is relative and there is always an interesting tension between ‘old’ and ‘new’ media. Joanna Sassoon notes how the digital recreation of ‘past-ness’ inevitably involves removing the marks of an analog time- scratches, blemishes, finger prints and dust. While many negatives were thus ‘sanitised,’ fungus had marked its own material traces on others and digital scanning enabled this to be visible. As vestiges of temporality the fungus created patterns that were like ‘new’ works of art. Perhaps these images will find their way to another version of the show in the future.

The ‘marks of time’, Portrait of a family in London, 1950s, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

What pictures would Jitendra Arya have chosen to show and how? We had to confront the difficult issue of cropping. In 1952 Jitendra Arya followed the location shoot of the Hollywood film Mogambo (John Ford) to Kenya and Tanzania. His sensational photographs of Ava Gardner bathing were carried as an exclusive in Life magazine in 1953 but there were many other negatives of Gardner on location. In one of them she looked across the river with her binoculars but a smaller original print had been cropped from top and bottom to give prominence to the star. This was understandable considering that the original context of the photograph would have been a magazine. Displayed in a gallery however, many years later, the un-cropped square format seemed to reveal more details about the circumstances that surrounded this picture that included not just the landscape and also her star status. In this picture Gardner is seated on a chair and has kicked off her high heeled shoes comfortably resting both feet on one of the shoes. The male members of the crew (clearly lower in the ‘pecking order’) sit at her feet or stand behind her.

Ava Gardner on the sets of Mogambo, 1953, Uncropped version, Jitendra Arya Foundation.

Jamie Baron points out that while archives seem ‘closer’ to the past they represent and are therefore potentially seductive in their seeming transparency, they are in fact more unruly and open to interpretation by new users. The ‘archive effect’ created through curatorial intervention in Light Works inevitably changed our encounter with a historical past. In the absence of references, one had to re-imagine and often re-fashion what Arya’s images might look like. The digital reproduction of the analog works inevitably resulted in altering the original and may further do so in the future. ‘Hand painting’ with Photoshop so many years later drew attention to how media cultures are sedimented and recurring phenomena- folds of time and materiality where things might be suddenly discovered anew (Parikka, 2012). The exhibition has also been a reminder of genealogies and continuities at a digital moment which is often amnesiac about an analog history. In this excavation of his archive, what decisions would Arya have taken? One will never know. Therefore, the show is ultimately an acknowledgement that a return to an ‘unmediated’ past is impossible.

References

Sassoon, Joanna. (2004). ‘Photographic Materiality in the Age of Digital Reproduction.’ In Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images, (Ed.). Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart. New York: Routledge

Baron, Jamie. (2014). The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audio Visual Experience of History. London and NY: Routledge

Jussi Parikka. (2012) What is Media Archaelogy? Cambridge UK: Polity Press

Sabeena Gadihoke is Professor at the AJK MCRC at Jamia Millia Islamia where she teaches Digital Media Arts. She started her career as an independent documentary filmmaker and cameraperson and was a member of Mediastorm, India’s first women’s collective that made three films on religious fundamentalism. Gadihoke was a Fulbright Fellow at Syracuse University during 1995-6 and has published widely. Her book on India’s first woman press photographer Homai Vyarawalla, Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla (Mapin/ Parzor Foundation) was published in 2006. Gadihoke has curated several shows on photography including a retrospective of Homai Vyarawalla at the National Gallery of Modern Art in three cities during 2010-11 and more recently a retrospective of Jitendra Arya at the NGMA Mumbai titled Light Works. Her research interests focus on the intersection of the still and moving image and she has written on contemporary documentary films, photo history, popular visual culture and female stardom in Bombay cinema. She is currently working on a book on photography and print culture in India during the 1950s and 1960s.

Comments