The Image in the Machine: AI Art and Its Implications

Installation view of Mario Klingemann’s 79530 Self-portraits (2018) at the exhibition Gradient Descent / Courtesy Nature Morte

When Google released the first set of images created with its DeepDream networks in 2015, the results were fascinating. Generated by training a neural network—which attempts to mimic mechanisms of the human brain—on a dataset of images, and then asking it to create its own visual manifestations, the resulting pictures seemed to synthesize many strands of a contemporary digital moment, aflood with visual information and methodologies of classification. At the same time, these beguiling, swirling pictures felt somewhat anachronistic, belonging to a speculative vision of the popular sci-fi imagination. There was a rift between the conceptual potential of an incredibly complex technology and the visual language that it ultimately employed.

At Gradient Descent, a recently concluded exhibition of art created using artificial intelligence (AI) at New Delhi’s Nature Morte gallery, the works on show seemed to have taken a significant step in closing this gap. Curated by 64/1, a research collective founded by brothers Karthik Kalyanaraman and Raghava KK, the show brought together a range of well-known and emerging artists working with different types of algorithmic systems. Mario Klingemann, Anna Ridler, Memo Akten, and Jake Elwes make use of video and disparate training sets to demonstrate their processes, while Harshit Agrawal and Tom White employ prints in different mediums as material manifestations of the AI. Diversifying not just the visual possibilities of AI but also uncovering its theoretical challenges, these artists offer a way to reconfigure our aesthetic frameworks. While I’ve written more extensively about the exhibition—and its limitations—elsewhere, I was confronted with larger questions about the implications of AI networks on image-making in particular. Specifically: how does the technology complicate how we consume an art object, material or otherwise? What is the next step for AI, and how might it affect artistic agency?

In my conversation with Kalyanaraman, a former professor of statistics and econometrics, he helps clarify some of these questions, gesturing at the significant historical and philosophical similarities between AI and photography, and the future of the mediated image under the gaze of the machine.

Arnav Adhikari: Without wanting to create a strict binary from the outset, do you view AI as a tool or a medium for art, and what are the consequences of thinking of it as either?

Karthik Kalyanaraman: That’s a fascinating question because if you see what happened with painting in the 1950s, in the time of modernist art critics Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, paint was always brought up as a tool to create images. But then people started talking about flatness, about the third dimension of paint, the surface of the canvas, and the medium itself starts to assume an importance it didn’t really have before. With AI, people have similarly been thinking of it as a tool primarily to create images, but one of the goals of 64/1 in trying to curate this show was to start to think of AI as a medium as well. Or rather, to reexamine the notion of tool and medium, because they are inextricably linked.

In 79530 Self-portraits (2018), Mario Klingemann uses an algorithm that amalgamates his own webcam photos with self-portraits by Old Masters, creating a strange, richly textured, and continually morphing tableau. / Courtesy Nature Morte

AA: In a recent piece, you expressed the parallels between the advent of the photographic medium in the 19th century and AI image-making in the contemporary moment. In what ways are the two forms linked or disparate? Could one augment the other?

KK: They’re certainly linked, and some of the debates about them are eerily similar. The early conversation was about how photography could be an art because it was just mechanically copying nature. How do we consider this art and where do you locate the creativity—in the brain of the photographer, the camera apparatus itself, or in nature? All these questions came up in the late 1800s and sure enough, we’re having exactly the same debate again with AI because again, you have this notion of creativity being displaced onto a machine, which is very unsettling. Creativity is still a mystery to us.

Another link is what the effect on other media is going to be. Photography had a slow but immense impact on every form of image-making including painting, which it radically changed. All the things that painting was striving to do with perspective and precision were suddenly devalued because photography could do them better and the effects were such that painting started to copy some of the innovations of photography—Degas was one of the forerunners there. Inevitably, painting needed to ask itself what it could do that photography couldn’t.

A third debate that’s happening is adjacent to the French film critic André Bazin, who argued that film and photography are about the poetry inherent in “reality,” shunning any form of manipulation of the photographic image. Now, of course, digital photography and editing complicate this. You then start to see some parallels to the problems associated with digital media: do we need these images to be a particular way? Is art about a material object, or can it just be about an image in someone’s head?

AA: That leads perfectly into my next question, which is about this fascination with the “final” image. Is the final picture that an AI creates more interesting, or is it the ephemerality or instability inherent to the technology? In other words, does the generative process or the “material object” mean more?

KK: Both. What AI art does is it foregrounds the process in a way that cannot be ignored by the ordinary art-viewer. What we are presenting is an algorithm that could potentially produce an infinity of images, of which we’re only showing a small slice, but it’s very explicit what is being presented. There are indeed seven artists, but really it’s seven human artists and seven AI artists, each one of whom could have produced these images. We can’t fetishize the image anymore, because, very pragmatically, what is the gallery selling? It could sell, as you’ve pointed out, the final image, which is either a segment of a video or a certain number of stills. But there emerges the same kind of problem that photography faces, which is, if you have unlimited editions of photographs, how do you preserve the scarcity value of art? One of the solutions leads into your second point, which is to not just sell a video, but in fact sell the process, by signing an agreement with the artist to not use that particular training set or the examples of images used to teach the AI that visual style, along with the specific algorithm used in that project. What you’re effectively considering art here is the affinity to create potential images, and not exactly these images themselves.

AA: You’re talking about it from the gallery’s perspective, but do you think that audiences are able to appreciate the visual manifestations of AI art in and of itself, or does the spectacle of its creation overshadow the work, at least at this stage of its development?

KK: If I put this in a crude form, you’re asking: are we selling AI Art or AI Art? Raghava and I have been following the development of the field over the last few years, when it really started with Google’s DeepDream, but the main reason we did not propose to curate anything was because it was all just fancy image-making, and all we would be selling would be AI Art. But even within the past year-and-a-half, it’s changed so much that there are distinct aesthetic sensibilities and concepts with each of the seven people we chose. The publicity has definitely been about the novelty of having a show built around art created by AI, but our hope was also that people would pay attention to the aesthetic questions raised and appreciate the images. Some people found certain human-plus-AI combos, if you will, more approachable than others; the more expressionist ones like Jake Elwes’s Closed Loop or Harshit Agrawal’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Algorithm, for instance. My sense was that people did start to appreciate the concepts at work and not just the AI creating art.

Closed Loop (2018) is a two-channel video by Jake Elwes that plays with both image and language. One network generates an image based on the thousands of photographs it has learnt from the dataset, while the other, a captioning algorithm, tries to describe it. The image then changes again to match the words in an unsettling tête-à-tête. / Courtesy Nature Morte

Closed Loop (2018) is a two-channel video by Jake Elwes that plays with both image and language. One network generates an image based on the thousands of photographs it has learnt from the dataset, while the other, a captioning algorithm, tries to describe it. The image then changes again to match the words in an unsettling tête-à-tête. / Courtesy Nature Morte

AA: The term “human-plus-AI” offers an interesting way into thinking about authorship. In postmodern and contemporary photographic practice, the found image features heavily, where there is a co-opting of both authorship and memory at play. How does image-making with AI fit into this paradigm, given the millions of images that a network is typically trained on, or the millions or images we consume? Where does this leave the question of authenticity?

KK: You can think of AI art to have been created pixel-by-pixel by a machine that typically has been given no instruction in line, colour, texture, or any other visual fact except the examples it’s seen, radically destabilizing how we think of creativity. But it’s also somewhere in the middle, between readymade or found art, where you’re putting a frame around something and calling it art, and that changes the way we’re looking at the object completely. Contrary to the traditional idea of the artist-as-genius, what’s happening here is something very immediate that Raghava calls the “artist-as-cyborg,” which is the idea that the whole process is spread out over the machine and the human. If you think about what makes Mario’s work different from Memo’s, it’s just the examples that the AI has seen and the images it’s trying to transform, but who gets to choose which image an AI has seen? It’s still the human artist.

AA: Is the ultimate aim to create neural networks that are able to replicate human composition and creativity, or is it to create an entirely new vocabulary of aesthetics altogether?

KK: Both. If you feed a neural network a whole bunch of paintings of Old Masters, like in Mario’s work, it’ll produce images with the texture and look of those paintings, so in that case, the goal is to imitate something about human creativity. On the other hand, if you look closely at Memo’s images and try to figure out what the medium is, you would think patches of it were created with drypoint or impasto, or that some patches look like photographs, which comes from the the fact that the AI has learned what these look like. But what it hasn’t learned is that it should not or cannot mix all these three things together in the same image, which is something we’d never think of doing or would find it hard to achieve.

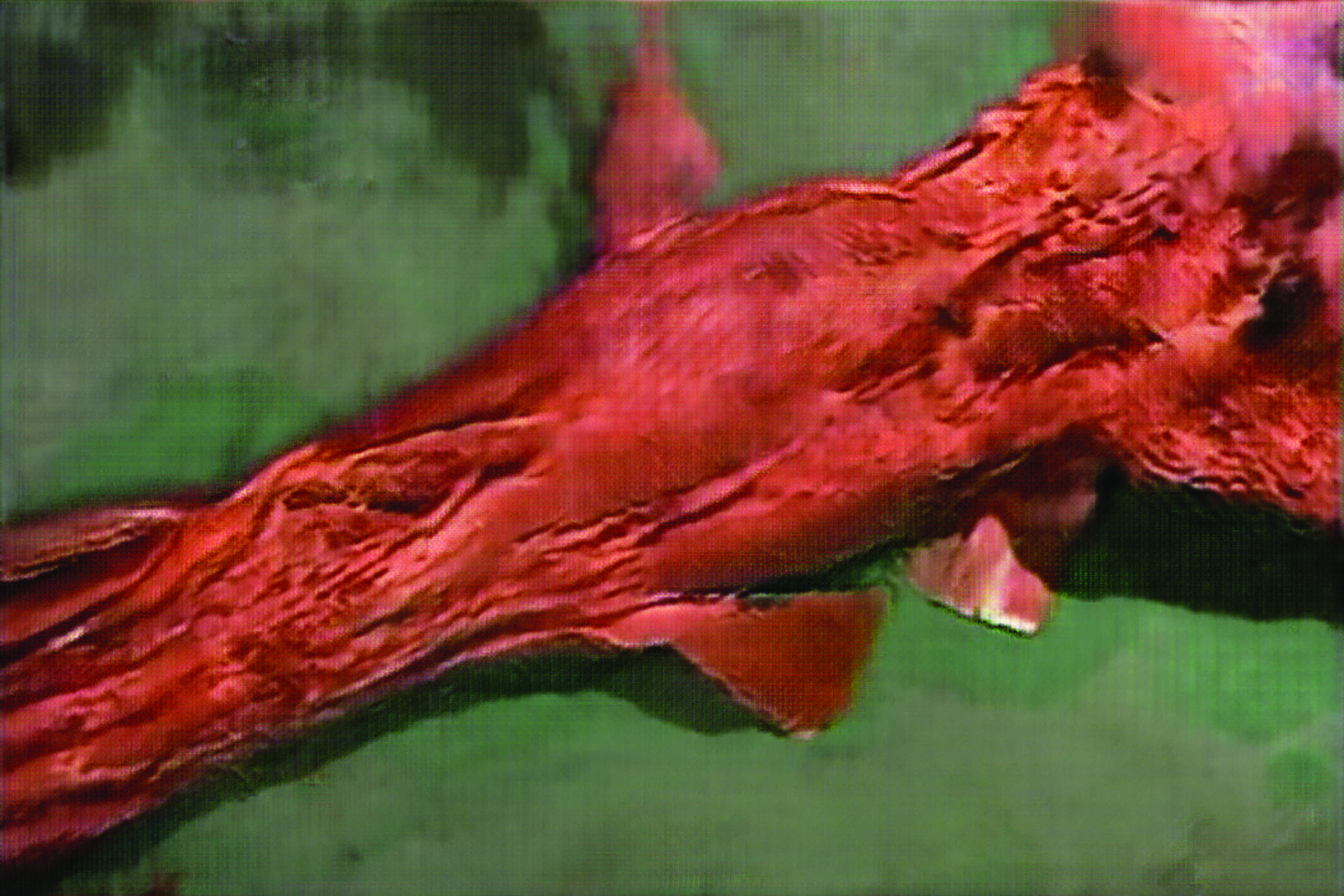

Harshit Agrawal trains the AI on images of human surgery in The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Algorithm (2018), and then allows the algorithm to produce its own images of imagined dissection. / Courtesy Nature Morte

Harshit Agrawal trains the AI on images of human surgery in The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Algorithm (2018), and then allows the algorithm to produce its own images of imagined dissection. / Courtesy Nature Morte

AA: I want to then ask you about the murkiness of the AI archive. In a digital moment where the photographic archive is ubiquitous and perhaps in peril, what might an archive of AI images look like? Or what does the archive mean for a system that generates or interprets millions of images?

KK: It’s a fascinating question, and there are artists who have approached it very differently, because the archive comes in through the training set, which relies on pre-existing images. You have for instance Anna Ridler, who uses it in a very unique way in her piece The Fall of the House of Usher, by creating the training set herself, which produces very different characteristics in the final image.

Because the archive is so important for all of this work, one of the constant themes that we saw in almost every AI artwork that we looked at was that of memory, of what is the difference between memory and imagination. The AI could only create new work based on what it has seen, or its human-curated memory, and the art lay in the surprising juxtapositions that the AI made between those images. When Jake’s video shifts from one image to another, some of the connections between those two images are not connections a human would’ve made, they’re connections the machine has made. That dissonance creates what I call a “poetics of metonymy,” putting two things that are next to each other and asking us to find links.

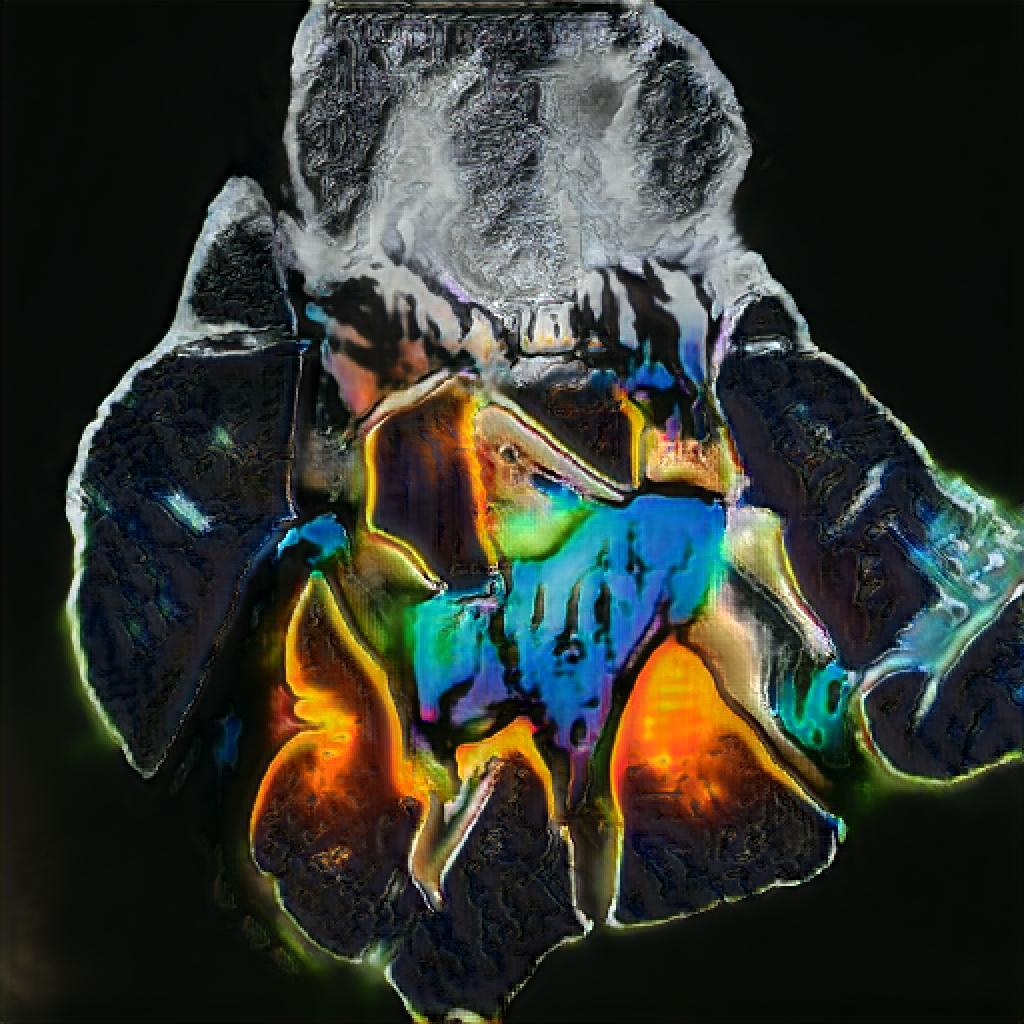

For his piece Learning to Dream, Memo Akten trained the AI on all the paintings in the Google Art Archive, which then brings up both your questions—not only the value of such a thing as the Google Art Archive, but the bias that is inherent in such a resource. If you see the paintings produced by this AI, there’s an unmistakable post-renaissance, pre-modern look to a lot of those paintings and it’s clear that the archive was primarily European. You can thus see biases in the dataset. The archive is not a value-neutral concept, it’s loaded with value.

A still from Memo Akten’s Deep Meditations (2018), which draws images from the Google Art Archive. / Courtesy Nature Morte

A still from Memo Akten’s Deep Meditations (2018), which draws images from the Google Art Archive. / Courtesy Nature Morte

AA: Where do you think AI art is going, or what are you most excited about? And what role might Indian artists, curators, and coders have to play?

KK: I think the work is going to become even more conceptually rich. There’s a kind of rapidly-developing AI that IBM Watson is working on called knowledge representation engines. This is an AI that understands connotation and denotation; it understands concepts, how they refer to objects in the world, and how they refer to other concepts in the language. Insofar as conceptual art is a play between denotation and connotation, metaphor and metonymy, AI art can very quickly start producing interesting concepts. I would say another decade, but one tends to be wrong with how quickly this stuff happens. But purely conceptual art, where the visual element is a translation of a piece of text and that text is more informative about the image than the image itself, is somewhere the AI can go, and is going. So far, semantic content has just meant recognizing objects in a painting, or creating a sentence about that painting, like in the image captioning algorithm that Jake had used.

One of our hopes and reasons behind pitching this show to galleries in India was precisely that we would love Indian artists to get involved in this new medium. We are in the early stages of conversation with Nature Morte about founding a lab to provide the infrastructure for young artists to work with this stuff. We don’t know if that will go anywhere, but that’s certainly something we’re thinking of.

In The Fall of the House of Usher (2018), Anna Ridler creates her own dataset of images, which are hand-drawn ink sketches of stills from the eponymous 1928 film. She then trains an AI algorithm on these sketches to generate its own images. / Courtesy Nature Morte

In The Fall of the House of Usher (2018), Anna Ridler creates her own dataset of images, which are hand-drawn ink sketches of stills from the eponymous 1928 film. She then trains an AI algorithm on these sketches to generate its own images. / Courtesy Nature Morte

Arnav Adhikari is an editor at PIX. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, Hyperallergic, and Apollo Magazine.

Karthik Kalyanaraman started out studying Baroque painting, but ended up with a PhD in Economics. He then taught statistics and econometrics at University College London and University of Maryland, College Park. Now, having returned to art, he works full-time with his brother Raghava KK heading the curatorial and art collective 64/1.

Comments