The New Studio Madras: An Oral History

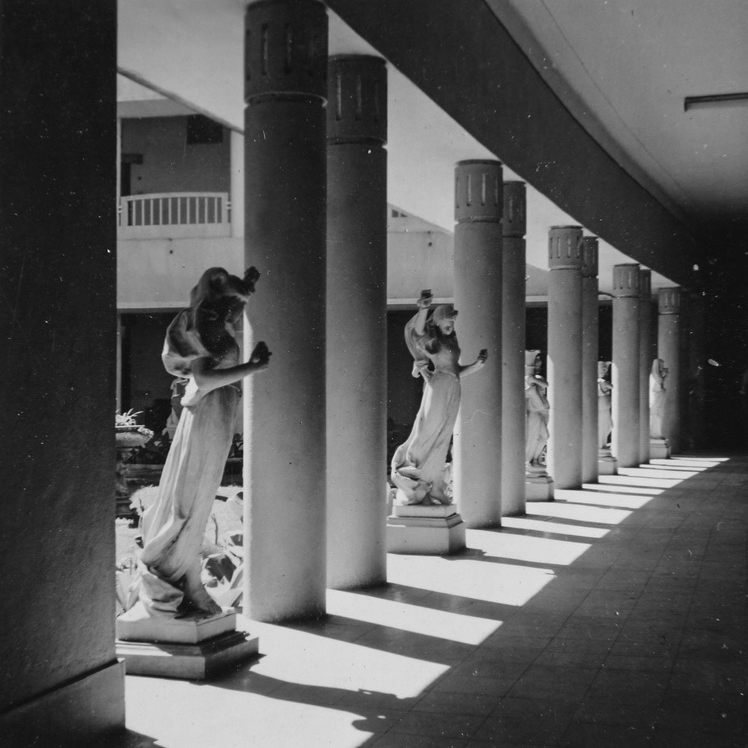

A photograph by C.B. Shastri on a film set in Srinagar, c. 1940s (New Studio Madras)

In 2016, one of the oldest running photo studios in the world, Kolkata’s Bourne & Shephard, was forced to close its shutters after 176 years in business, signalling that perhaps the era of the commercial photography studio was finally coming to a close. Once the locus of technical innovation and experiments with film and portraiture, studios in India—if not South Asia—have gradually lost their currency and sustainability for image-making.

For this week’s PIX Post, Rishi Kochhar, a masters student at the National Institute of Design, shares an oral history of one such studio in the city of Jammu. Unassuming at first and tucked away in the bustle of a busy market, the New Studio Madras has a fascinating past. Its founder, C. B. Shastri, was a maverick at his craft, a photographer and studio technician who would constantly update his practice to learn about new forms. Kochhar provides a rich portrait of the advent of Shastri’s studio, and its parallels with the nation’s political and cultural histories.

The New Studio Madras, located on Residency Road, is nestled within the hustle and bustle of Raghunath Bazaar, a flourishing marketplace in Jammu city, and is run by sixty-year-old Chandan Sunder, who has been overseeing the studio for almost four decades. In our first meeting he seemed like an inquisitive man, with an attention to detail and a calm demeanour, going about his business patiently.

Similar to most surviving photography studios in the country, which are now run by second or third-generation photographers or have been handed down to heirs, the New Studio Madras is a family operation, founded by Chandan Sunder’s father, Chandan Bhadram Shastri in 1965. During his adolescent years, Shastri, who migrated from Andhra Pradesh to Jammu and Kashmir at a young age, originally trained as a painter and then slowly started using the photographic medium in the pre-Independence era. He travelled and worked across cities like Madras, Calcutta, and Bombay, where there was a proliferation of photography studios. While in Bombay, Shastri assisted the noted cinematographer Radhu Karmakar, who worked extensively for R. K. Studio and shot most of Raj Kapoor’s films. This training prepared Shastri for a life behind the camera and helped him acquire the tools he would later employ in a prolific career.

In his late forties, Shastri returned to Jammu and Kashmir and soon lost his father, an absence that shook him and abruptly placed upon his shoulders the burden of considering a stable, rooted existence. He spent some time working in studios in Srinagar, Jammu, and Poonch. As the famed, mystical valley with breath-taking gardens and scenic views, Kashmir attracted more photographers and artists than any other region in the state, providing a plethora of opportunities for studios and photographers looking to gain a foothold. Shastri worked at a few of these studios at the time, including the legendary Mahatta & Co. and Preco Studios Private Limited in Srinagar, the latter of which, like many studios in the region, had a branch in Jammu that only opened in the winter due to the unbearable cold in the Kashmir valley.

In the initial early years after Independence, the country was in turmoil. The British made a hasty exit and the preparations for Partition had been shoddy at best, resulting in widespread violence and chaos. Over the next decade, while the nation nursed its wounds and tried to navigate the prevailing uncertainty of a newly independent administration, there was also the hint of a fresh beginning.

Under Jawaharlal Nehru’s leadership, the government promptly set out to realize his vision of revitalizing the economy by improving agricultural production, and investing heavily in industries like coal and steel; industrial and scientific progress became emphatic markers of a modern India for Nehru. Creative and literary pursuits had consequently taken a backseat to compensate for the large demand for engineers and other allied professions required to fuel the ambition of the young modern state. As most of the youth at the time aspired towards government jobs which provided stability and a steady income, photography was far from being considered a secure occupation, and even young hobbyists opted for “nobler” pursuits in an attempt to contribute to their nation’s economic progress.

Before Independence, when the freedom movement was at its peak, Chandan Shastri was drawn to the significant events being organised across the country and the charismatic freedom fighters that were leading the struggle. Living a largely nomadic existence, Shastri used a light, 35mm Leica, akin to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s, on his photojournalistic endeavours, where he captured the likes of the Indian advocate, Vinoba Bhave (aka Acharya). Sunder faintly remembers printing his father’s portraits of Bhave, but admits that those negatives have likely been lost somewhere in the archives of their residence. Many more plates and negatives have met a similar fate over the years, a part of our history lost in the process.

Near the Vaishno Devi shrine in Katra, c. 1930s (C.B. Shastri, New Studio Madras)

Near the Vaishno Devi shrine in Katra, c. 1930s (C.B. Shastri, New Studio Madras)

The Studio Years

In 1965, Shastri eventually opened the New Studio Madras, a nurturing ground for Chandan Sunder, who was only ten years old at the time. Sunder recalls how he would often spend his evenings at the studio after school, carefully observing, learning from his father, assisting with studio work, and developing his first black-and-white film roll while in the fifth grade. He was a fast learner and was fascinated by the chemical processes involved in the darkroom. By 1965, the wet-plate process became passé and new sheet films were in use. Sunder explained how large-format sheet films were mostly 10×12 inches but were more often of a vague rectangular proportion. Shastri used a few old wooden cameras, which employed glass plates 11×14 inches in size, although they were mostly used to photograph large groups. These cameras had a manual lens focus, flexible bellows, and were propped up using wooden tripods. The New Studio primarily operated German equipment due to Shastri’s preference for German workmanship, and in their initial years had up to three cameras including a Linhof, a Rolleiflex medium-format twin lens reflex (TLR), and a large-format wooden camera which was produced in South India. According to Sunder, his father also used English-made lenses, which he’d have imported through friends.

Shastri later shifted to using the Rolleiflex, an East-German Pentacon Six 120mm SLR, and then a Japanese Mamiya C330 TLR with interchangeable lenses in the ’70s. Having worked with a diverse range of cameras, Shastri had a knack for repairing them, a valuable skill given the paucity of professional technicians at the time. Sunder remembers when the information department of Jammu and Kashmir had purchased a medium-format Hasselblad camera that had broken down. In the early ’70s, Hasselblads were only repaired in Bombay for a hefty five-thousand rupees in addition to transportation charges, and would have required a minimum of two months to fix. The Director of Photography at the state department, who knew Shastri personally, had requested him to carry out the repair instead. Shastri, who had agreed and asked for three months and three-thousand rupees was able to restore the Hasselblad to working condition within a week, and gave it to Sunder to explore and photograph with for the remaining two months of the contract. Sunder was predictably ecstatic.

Sunder’s own first personal camera was a Russian-made Zenit 35mm SLR, acquired after the New Studio Madras helped a team of Russian engineers who were overseeing the Chenani Hydroelectric Project, with processing their black-and-white film in the early ’70s.

In 1977, Shastri, a member of the Royal Photographic Society and the Federation of Indian Photography, took Sunder to a national convention in Hyderabad celebrating the FIP’s Silver Jubilee. He recalls how inspiring the event was in motivating him to take the plunge into the field. He consequently invested in more advanced equipment, purchasing a Minolta SR-T 101 35mm SLR, and started gradually taking over the New Studio’s commercial work while exploring his own interests in landscape photography in the region.

Sunder began sending his work to national salons and contests at this stage, hoping to gain exposure and recognition for his work. He began corresponding with the monthly journal Viewfinder, published by the FIP, submitting a couple of entries each month for their beginners’ contest, wherein a judge nominated by the Federation would pick the winners and provide technical guidance and feedback for each entry. Sunder steadily rose through the ranks and soon qualified for the advanced section of the journal.

Chandan Sunder at the FIP convention in Hyderabad, 1977 (New Studio Madras)

Chandan Sunder at the FIP convention in Hyderabad, 1977 (New Studio Madras)

Sunder began to take up most of the responsibilities of running the studio work by the mid-’80s, around the same time that colour photography was being introduced in the Jammu area, though only few studios in Srinagar had the capacity to process colour film. Sunder’s father processed his first 120mm Kodak colour film in 1967, when he’d shot in Ladakh for the tourism department using his Rolleiflex. Shastri’s membership to the Royal Photographic Society enabled him access to magazines and journals published by the RPS that regularly carried information about the chemicals required and the step-by-step breakdown of film-development processes for its readers. This allowed Shastri to procure the required chemicals and compose his developers, stop baths and fixers independently. He had a strong preference for mixing chemicals himself and rarely relied on readymade ones available in the market. He would even would wait for months for a small amount of a certain chemical to arrive from England. Shastri was well-versed in the chemistry of the process and passed on his skills to Sunder over their years spent in the darkroom together. But as the bulk of photographic work at the studio started shifting to colour and the developing process becoming more complex, Sunder too shifted to buying readymade chemicals.

Painted Photographs

Colour is in many ways the essence of life in India—its ubiquity is reflected across cultural traditions of the country. The regional painting of Karkhanas (artists’ workshops), for example, have been present for centuries, later evolving into the Mughal and Rajput styles of miniature painting. When black-and-white photography was introduced in the subcontinent by the colonialists, there was a tension created between this existing painterly, colour tradition and the newer, alien medium of image-making.

The painted photograph, or coloured portraiture, can then be viewed as a response to the colonial encounter, an amalgamation of objective documentation and artistic manipulation, adding life to monochromatic portraits. Indian royalty and the burgeoning middle- and upper-middle classes adopted the new medium while combining it with indigenous inflections. The artists in royal courts were thus retained even after photography entered the scene. Instead of abandoning them, their patrons now employed court painters to to apply colour on photographs, as they had done for centuries on canvas or paper.

In the 19th century, not many would have enthusiastically claimed that the practice of painting on photographs would thrive. In retrospect, it survived well up until the digital revolution, when it was slowly phased out by film photography of the late-20th century. The New Studio Madras, however, had been using this painting technique since its inception, initially starting out with oil, charcoal, and watercolour on prints and negatives, turning primarily to water colours in later years due to a lack of skilled artists. Like with so many other techniques, Sunder’s father was himself a specialist in the form.

The New Madras Studio used Fuji and Camel water colours meticulously by diluting them and then applying them layer-by-layer directly onto prints. They also carried out colour toning of prints and had a variety of tones on offer, including sepia, cobalt, and blue. Sunder let me in on a trade secret while explaining the process; he says that one could not use water colours on the shadow (black) regions of the print and therefore, as his father had suggested, they would first add the sepia tone to the print and then proceed to watercolour the blacks (which had now turned brown under sepia toning) in different shades of dark colours. Oil paint, on the other hand, worked differently due to its opaque nature. There existed many such techniques used by artists and studios alike to create a realistic, colourful reproduction of reality.

In the days of film photography, there was a also large amount of retouching and finishing required before a photograph was considered complete. Akin to most studios of the era, Sunder’s also used lead and wax pencils to retouch negatives, creating different densities and ensuring skin blemishes and other processing marks were cautiously removed. Similarly, one could use lead pencils and brushes and employ different inks for artistic manipulation of a print. Most of this tedious work was carried out manually and required a devout, patient attention to detail, often requiring hours and days to retouch some photographs.

The fascinating part about painted photographs is the extent of artistic manipulation involved. According to Sunder, most often, colours were not simply reproduced as per the real scene, but were actually revised to create a more harmonic and balanced setting. This kind of “fudging” was usually possible only in portraiture created in studios or outdoors using backdrops. Artists and photographers had a more difficult task painting on images of natural landscapes, unable to manipulate colours with consistency.

These techniques were most efficiently applied in marriage portraiture. In India’s widely prevalent tradition of arranged marriages, the initial point of contact between the two families was quite often through an exchange of photographs between potential brides and bridegrooms. Large portions of the studio’s clientele were soon-to-be-married men and women, and they often entertained requests for change in skin tones, sari colours, and blazers to create a more appealing image to perhaps increase the chances of matrimony. Retouching was thus not only restricted to black-and-white film but extended to colour film and prints as well. Sunder explained how, while the colours couldn’t be changed in a colour negative, the tones could be influenced using colour lead pencils. Slowly, however, as affordable DSLRs flooded the market at the turn of the 21st century, and most of the post-processing shifted to digital software, the art of hand painting on photographs entered its twilight.

(Above) Maharana Fateh Singh of Udaipur, gelatin silver print and watercolour, c.1920-1930. (Below) Seated lady, gelatin silver print and watercolour, c. 1920-1940. (From Painted Photographs: Coloured Portaiture in India, Alkazi Collection of Photography)

(Above) Maharana Fateh Singh of Udaipur, gelatin silver print and watercolour, c.1920-1930. (Below) Seated lady, gelatin silver print and watercolour, c. 1920-1940. (From Painted Photographs: Coloured Portaiture in India, Alkazi Collection of Photography)

The New Studio Madras has persevered through the digital age and continues to serve customers today. Sunder has now added a Canon, Nikon, and Pentax DSLR to his arsenal and still overlooks the business. The studio now covers weddings, ceremonials, product shoots, commercial and industrial shoots, and portraiture. Sunder even pursues his own documentary projects and maintains that neither he nor his father ever had any qualms about shooting in any particular genre. He recollects how his father had the reputation of being the most expensive photographer in Jammu, although people across distinct economic backgrounds and social circles used to visit the studio during its peak. They made the most of what came their way and even today, the major chunk of their earnings come through marriage assignments and studio portraiture, though business from the latter is diminishing.

Sunder now spends his days lazily traipsing through the New Studio. On a typical day, he visits in the afternoon and after taking an account of the morning’s events, settles in for a quiet cup of chai and a cigarette. He often reminisces about the days of film processing and when studios were the only avenues for making portraits. But Sunder does not loathe the digital age and accepts that change is the only way forward. He engages in discussions about trends in contemporary photography and talks passionately about some of his favourite contemporary artists. With the photo studio business diminishing over the years, the New Studio Madras is truly a relic of an era of photography now well into its decline.

The New Studio Madras is nestled on Residency Road, in the hustle and bustle of Raghunath Market.

The New Studio Madras is nestled on Residency Road, in the hustle and bustle of Raghunath Market.

C. B. Shastri founded the New Studio Madras in 1965

C. B. Shastri founded the New Studio Madras in 1965

Photographs by Chanden Sunder (New Studio Madras)

Photographs by Chanden Sunder (New Studio Madras)

Rishi Kochhar, an architect by training, is currently pursuing a Master of Design at the National Institute of Design in Gandhinagar. His work is concerned with issues of narrative memory and identity, and has been exhibited at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in New Delhi in 2014, as part of the student show, Prarambh.

Comments