The sonic imagery of Savinder Bual

Savinder Bual, Pineapple Project, install shot at PEER, 2020, image credit Stephen White & Co.

When an artist is considered ‘South-Asian’ or as part of the diaspora, they are parenthesised within a geo-cultural frame. However, a more layered and multivalent approach to these and other artists’ works is needed for unearthing more than the narrative of post-colonial displacement or for simply articulating their current civilian or locational status.

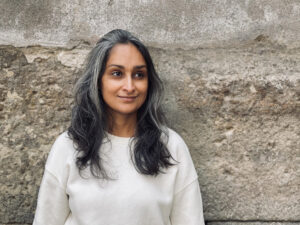

Savinder Bual, a visual artist based in Hertfordshire studied photography at the Royal College of Art, London (2010) and consciously steered away from ticking any identity-enclosing boxes while building her career as an artist. She was keen to push away from what she felt was expected of artists of colour. Hence, Bual chose not to apply for grants that inadvertently privileged her ‘heritage’ over and above the very situatedness of her practice. Although this may have slowed down the moment of her being recognised through public acclaim, it made her focus on aesthetic sincerity and cultural research beyond the weighted and sometimes forced facets of nationhood, identity and home, usually expected of so called ‘non European’ artists. Working outside the fetters of nationhood or nationality, the key to her work lies in media experimentation with film, sound and mechanical devices.

She recalls an incident from the Royal College of Art, when she was asked by one of her tutors: “Where are you in this work? I can’t see you in it.” At a time when there were only a fews students of colour in the course, this question/proposition led her down a path of self-discovery, and the need to communicate with a diverse viewership.

Savinder Bual, Javasu, installation at Caraboo Projects, 2019. Image courtesy, artist

We enter a phantasmic world – a giant sea monster creates ripples of forgotten maps, pineapple heads sound stories of time. Bual’s practice further involves engaging with sound, images, maps and kinetic objects, inspired by eighteenth and nineteenth century mechanical inventions. These material and phenomenal sources carry discursive and epistemological residues of colonial trajectories, and are propelled into the contemporary through moving image and other pre-cinematic and digital mediums. In referring to herself as a ‘cinema pioneer’, Bual constructs an identity around chapters of European cinema history, that were predominately (white)male-dominated, with inventors such as Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), Augustin Le Prince (1841–1890), Thomas Edison (1847–1941), the Lumiére Brothers and Georges Méliès (1861–1938).

With reference to constructing an identity in relation to cinema, Bual says, “this is a little bit tongue-in-cheek, but addresses some of the implied notions of identity (for instance based on colour and origin) and home.” However, the very location of home for Bual has shifted with time – China, India and Ecuador.

Describing her work as being process-driven, The Pineapple Project (2018) was initiated in India during her residency at 1Shanthi Road together with a workshop at Jaaga Bengaluru in 2016. Similar to her other works such as Projector (2011), Flying Works (2014), Javasu (2019) and Fade (2020) this project also emerged as a pre-cinematic experiment. A pineapple head was manually placed on a rotating device by one of her animation workshop students. The artist was fascinated by the hypnotising effect generated by the spinning leaves.

On returning to her studio in the UK after her residency, the artist began experimenting with similar objects but was dissuaded by many sound technicians from making an actual instrument. However, when the leaves of the pineapple accidentally struck the device, Bual was convinced she heard a “musical scale” . Therein lay the seed for her invention of a pineapple instrument – each one eventually generating a unique sound. It took the artist one and a half years, and the advice of innumerable gourd instrument experts in Ecuador, in order to finally craft the first prototype.

With nine unique gourd instruments in hand, the artist proposed and performed The Pineapple Orchestra at the Bristol Beacon (formerly Colston Hall) in November 2018. The artist was keen for the community around it to grow organically rather than through workshops which brought together a diverse group of people through invitation. The Pineapple Project was a direct response to the artist’s frustration emanating from facilitating workshops with a number of organisations whose intention was to bring more diverse audiences to their spaces. Bual says, “this translated into bringing enough people of colour through the door. Yet, these workshops were always tokenistic gestures. The organisations would not do the real work to really bring in a diverse audience. Rather, they were just making sure they ticked their boxes for future funding.”

The artist decided to then approach this “problem” with music. The group created through The Pineapple Orchestra was one where people were listening to each other. Sixteen members of the public, some who had never played a musical instrument before formed the orchestra. Since the instruments were new inventions, they created a blank canvas to work from. The orchestra participants dedicated themselves to rehearsals, responding at first to the sounds generated from the instruments in falsetto and were subsequently directed by a composer. The seed that was planted by Bual eventually led to a strong sense of community.

On the other hand, the pineapple as an object, also gestures to a dark colonial history. This exotic fruit journeyed from South America to the U.K. on the ship and later became a symbol of opulence. The associated exoticism of conquered worlds became another potent metaphor as seen in the Dunmore Pineapple folly in Scotland. The pineapple was grown in hothouses in the U.K. and its presence in a household signified wealth and power. Sometimes, to impress their guests, owners of this precious fruit often rented them as dinner-table decor. Though narratives of slavery and oppression associated with the making of the Empire are not usually associated with this fruit specifically, Bual’s, artwork brought this forward in conversations through ‘deep listening’ sessions during the Pineapple Orchestra’s rehearsal gatherings.

Savinder Bual, The Pineapple Project performance, 2018. Documentation: Florence Pellacani

As a trained photographer, Bual translates her need for precision into ‘visual sound’. She says, “it’s all about slowing down, listening and noticing, not taking things at face value and going a little bit deeper to have the space to think and imagine between the gaps and beyond the image.” As a lens- based artist she plays with the medium of light to sometimes accentuate and then erase areas, creating different planes of focus and impression. She confesses that she still thinks in technical terms: F-stops and fixing frames when formatting her works. This method of localised editing, of creating a layered sensibility addresses the way in which she melds one form into another. This is evident in some of her video works such as: Flicker (2004), Train (2009) and Road (2011), that use animation and a single image.

The notion of subconscious residue is perhaps also present, and can be observed in the work Pinjekan (2019), wherein the movement of the viewer activates a distinct flapping sound and further animates the image. Javasu (2019) and Movements of a Flatfish (2020) undergo a visual metamorphosis as they pass through bamboo rollers. While both these works are about Bual’s interest with the moving image and photo montage, they also go back to her personal and lasting interest in myth and folklore as expressed through traveler maps and sea monsters, described earlier in the piece.

The artist’s most recent work, Fade (2020) further ties in her decade-long vocabulary developed with sound, photography, moving image and machinery. Inspired by a novel, self-recording tide gauge (that drew waves on a paper to mark the shifting intensity) from the Isle of Sheppey, Bual was fascinated with the idea of the sea itself making creative forms through its organic flow. To mimic this, she created a ‘kinetic installation’ that is activated with the movement of water. While the visual itself is a seascape projection of a 35mm slide, it transforms as the water drips from one vessel into another gradually flooding of the image. The sounds emitted from the stainless-steel vessel resonate and echo to fill the entire space.

This semiotics of image and sound, and the way they transcend barriers of language and culture has had a major impact on the artist’s engagement with her audiences. The sounds that act as foleys, convert a visual image into an immersive experience. Bual’s intentions with her works, journeying into the future from hereon, are to instigate change, wherein accidents become creative components that spontaneously contribute to the discovery of multiple centres, resounding with new discoveries and encounters.

Savinder Bual, Fade, video, 2020. Documentation : The artist

Savinder Bual studied painting at Winchester School of Art and Photography at the Royal College of Art, London. Since then, her work has been screened and exhibited widely, including at Bloomberg New Contemporaries; Turner Contemporary; CCA, Wimbledon Space, Focal Point Gallery, Animate Projects, Peer Gallery, Standpoint, The British Council, 1Shanthiroad, Bangalore and OV Gallery, Shanghai.

Read more about the author, Veeranganakumari Solanki here.

Comments