The Vintage Distortions of Nandan Ghiya

“Existential Angst,” 2013, from the series Download Errors, is a daunting declaration about the state of our existence, a reminder of our failed and failing attachments. All installation views from Ellipsis: Between Word & Image.

The history of photography in India, and Rajasthan in particular, is as speckled as the tints that artists once used to adorn a still image. Brought through colonial influences, photography was at first a means of scientific and anthropological documentation. The nobility were the vanguard practitioners and patrons; think Sawai Ram Singh II of Jaipur, known as the “photographer prince” whose benefaction was particularly pivotal to the medium’s dissemination within the desert state. The miniature art tradition, which thrived in and around North India, soon segued to photography, and Rajasthan became an important centre of patronage and incubation for photographer-artists.

While black-and-white photographs are traditionally thought to possesses an erudite quality, in the hands of native Indian photographers, gray-scale images took on a new life, suffused with bright colours. Before long, bazaar or marketplace studios proliferated across regions, sustained by the bourgeoning mercantile class who were enthralled with this unique mode of visualization. The photographer-artist thus emerged, lending this craft a new aesthetic. His—as it was typically “his”—methodology was informed by the subcontinent’s longstanding cultural fixation with colour distilled through the heritage of visual storytelling. The artist tinted achromatic images, embellished details of garments and jewelry, and later staged elaborate backdrops, challenging the inherent authenticity of the photographic image. His concerted effort nurtured by continuous interdisciplinary and cross-cultural inputs fostered a new model of image making, melding photography, and indigenous art practices to create a new artistic idiom.

This historical backdrop informs the practice of Nandan Ghiya, a Jaipur-based visual artist who works primarily with vintage photographs. At the recently concluded exhibition Ellipsis: Between Word & Image at the Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur, a section of the show displayed a mid-career retrospective of Nandan’s works spanning a decade.

Nandan’s grandfather was an eminent photographer-artist in Jaipur, while his father is a dealer of Indian art and antiquities. Having trained as a designer at the National Institute of Fashion Technology in New Delhi, Nandan’s social framework, familial profession, and formal education have converged to create a distinctive visual language that embodies what he calls a “coexistence of odds,” a core principle of his practice.

By “vandalising” distinctly Indian vintage photographs that carry vestiges of history, Nandan imagines the fate of these “archaic” images in the contemporary era of compulsive image-making and self-documentation that pervade our screens and lives. There exists a strong undercurrent of regional affiliation in his practice, discernible in his choice of raw material, colour palette, and finishes. As someone who has been close to his artistic process for a number of years now, I have witnessed Nandan staying true to his cultural upbringing. His practice is an aspirational outcome of convergent introspection, and his works a somewhat dissonant amalgamation of the iconographies of the local visual vernacular and digital screen.

The Chairmen, 2012 – 14. Foraged vintage photographs are embellished with emblems of the digital zeitgeist, lending them a mutable contemporaneous relevance.

Nandan forages forgotten and discarded vintage photographs of mostly Rajasthani origin, and works with them with a scientifically investigative approach: he curates and collates images based on tangible and intangible similarities, choosing from an ever-expanding collection that he’s assimilated over two decades. He almost always works directly on the photographs themselves, painting and splicing. His process is organically perceptive, contrasting inherent and acquired aesthetics and observations. Values are added gradually; some of his works take years to reach completion and yet hold within them the possibility of further exploration.

Nandan is driven by a tenacity to distort literally the vintage photographs he has been taught to venerate , to blur the lines between the real and the virtual as if to create his own parallel reality. Much like the photographer-artist of yore, who painted upon images illusory backdrops, jewelry, and elaborate facial details to elevate the mundane to the fantastical, Nandan’s work deploy markers of past and future to create imagery that traverses spatio-temporal boundaries.

The series Download Errors (2012) offers a sardonic illustration of the Internet Age and its fundamental ephemerality by investigating the value of an image in the era of Google Search, clip art, and stock photos. The works looks like the outcome of a malfunctioning digital display, replete with glitches, error-message boxes, and pixels, alluding to the gradual annexation of a collective mindscape by the propensity of digital screens. Incidentally, these glitches might make the antiquated photographs relevant again, resuscitating and delivering them into the 21st century.

One of the most striking pieces from Download Errors is “Existential Angst,” a large-scale installation of photographic frames forming the phrase “Attachment Failed.” The frames, fashioned to form individual pixelated alphabets, contain images of couples whose faces are blurred by the artist as if to protect or obliterate their identities. The message, typically displayed on a computer screen in the event of a weak network connection, is a routine occurrence, a minor inconvenience. However, when blown up, it manifests itself as a daunting and profound declaration about the state of our existence, a reminder of failed and failing attachments: to individuals, community, location, history, and memory.

The recent stretched and pixelated work “DSC2065,” with the image of the revolutionary Bhagat Singh marks the initiation of a new direction for Nandan’s practice. The frame, which was once thought to confine and protect the image, is here overextended in tandem with the profusion of digital intervention in everyday, analogue experience. It is convoluted, as if challenging the status quo of an image in real time. With the pixelated frames, Nandan’s works take on a dynamism that pushes the margins of the image and its inherent identity. The wall is integrated into the artist’s canvas and newer viewpoints trickle in.

“DSC2065” (2012). The frame, which was thought to confine the image, is overextended and pixelated in tandem with the profusion of digital intervention.

With the Blue Screen series from 2014 onwards, Nandan’s process has surpassed concerns of identity, focusing instead on the lassitude of digital surfeit. Images have been fragmented and flattened with a specific shade of blue used prolifically in hoardings, billboards, and local signage, a counterintuitive response to visual profusion, a ritualistic cleansing that brings a meditative focus back to fundamental elements of the lines and shapes of objects. The objective of Blue Screen was solely to declutter and create blank spaces, representing voids in the memory map, that can be filled with subjective whims or icons.

The digital screen is further emulated, almost compulsively, in newer bodies of work post-2014. It is ironic that while Nandan’s practice began as a scathing appraisal of the deleterious impact of the virtual, it is now modeled after its visual standards. The circle of disenchantment appears to have been complete with the permeation of the New Aesthetic in his process, drawing upon James Bridle’s theory that describes a coalescing of the digital into the physical world.

From the Blue Screen series, 2014. The images seem to be fragmenting and elongating, stretching out of its confines, effectively turning the wall into one large glitching screen.

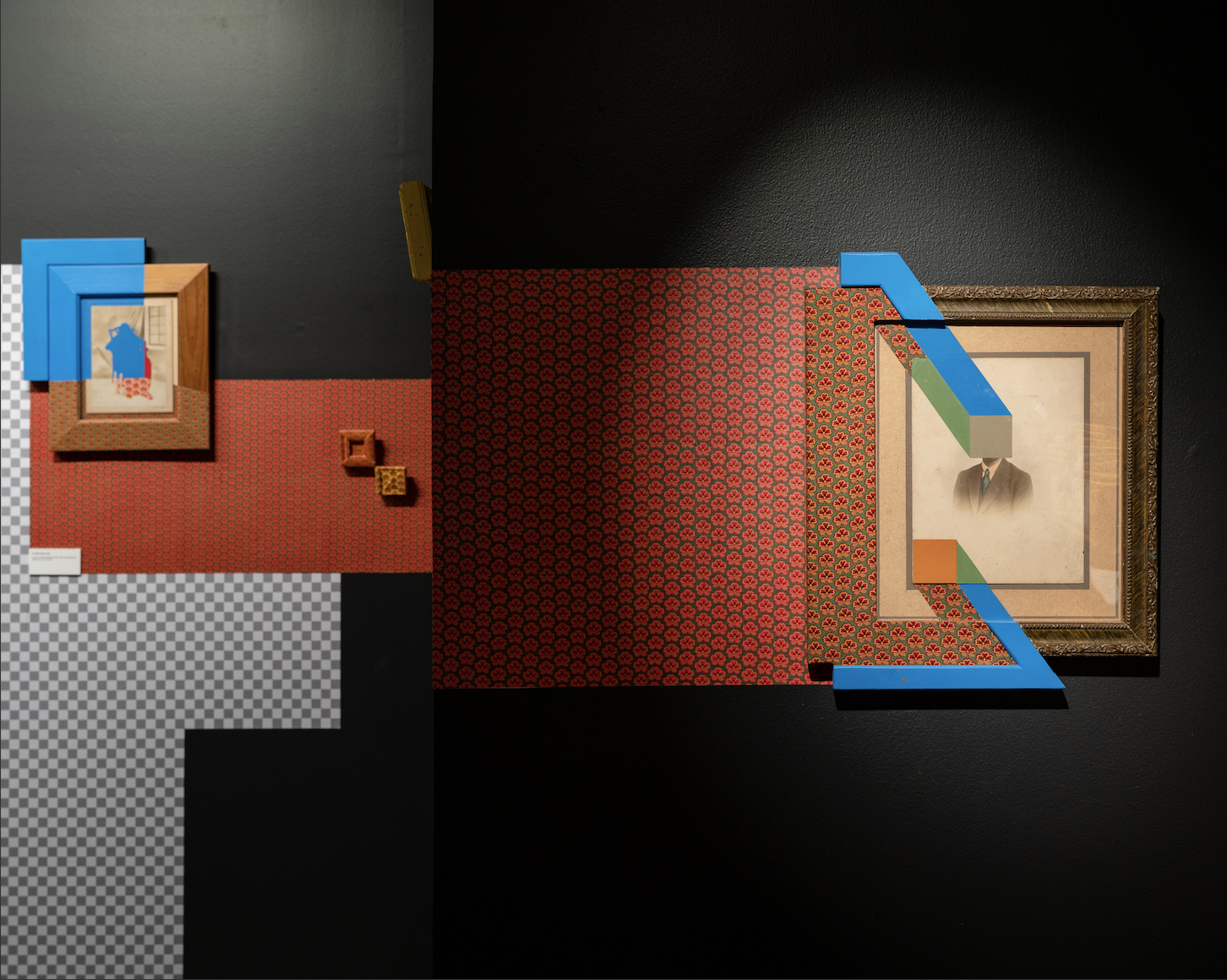

The primary images Nandan uses for his latest body of work called Chaura Rasta Neighbours, created for Ellipsis, are from a series of late-20th-century oil-painted photographs by a Jaipuri bazaar artist. These are static portraits of ordinary people that depict the relative austerity of image-making of that era, paradoxical to the current trends of imaging culture. To Nandan, they serve as the perfect blank canvas to experiment with manifestations of the ego and superego in an attempt reexamine the complexities of digital identity and consciousness. A number of graphic values, along with vintage imagery, are deployed—camouflage, floral prints, Photoshop background checks, watermarks, pixels, and distortions—to denote the subtle invasion of digital forces that slowly chip away at human cognizance. The works seem to be mutating to the point of disfigurement and allude to the many layers of the shape-shifting self.

Chaura Rasta Neighbours is a dystopian projection of virtuality and its intrinsic liabilities, the leitmotif being the insatiable pursuit of attaining the all-encompassing persona. The relentless projection of self takes precedence over the subject, who progressively loses authority, and is rendered an object governed by digital filters, backgrounds, and the glitches that come ascribed with them. The works thus seem to be frozen in an elusive moment of transience. This meditation on liminality is increasingly present in Nandan’s new works, which are also beginning to take on an immersive quality, often spilling and distending, turning wall space into a large, dynamic, glitchy screen.

The scope of Nandan’s practice seems to have surpassed his own digital weariness, and appears to be growing with the magnitude of digital culture. His palimpsestual works evolve as a pertinent allegory of the binary existence of emerging “internet tribes,” which are struggling to find its footing between the long-standing histories and a rapidly globalizing world. Photography in the digital age is stifled as a form of artistic expression and increasingly rendered a commodity, even though its scope has grown exponentially with the surge of new-media practices and heightened engagement. The authenticity of authorship is debatable and becomes entirely distinct from the subject of the image.

Against this framework, Nandan’s narrative becomes an iconoclastic critique of the meaning of imagery and its subsequent consumption. The past is layered with emblems of the digital zeitgeist, with a view to interrupt the preordained metaphor of vintage imagery, lending it a mutable contemporaneous relevance. By reinterpreting the iconography of traditional studio photography through subversive methods, Nandan is at once paying homage to his cultural and locational history, while rupturing 21st-century tenets of image-making.

Chaura Rasta Neighbours, 2018 – 19. The images seem to be mutating to the point of disfigurement.

Chaura Rasta Neighbours, 2018 – 19. The images seem to be mutating to the point of disfigurement.

Nandan Ghiya’s work was featured in “Nandan Ghiya’s Spectral Emanations,” as part of the exhibition Ellipsis: Between Word & Image, which also showcased photographs and text from the PIX archives. The exhibition was on view at the Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur between 15th February – 30th April, 2019, and was supported by Exhibit320, Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust, and the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts. Installation views by Philippe Calia and Srinivas Kuruganti.

Shaivyya Gupta trained as a fashion designer, and divides her time between doing innovative experimentations with the craft of hand-block printing and freelancing as a fashion designer, art collaborator, content writer, and design faculty.

Comments