The Place of Shahidul Alam

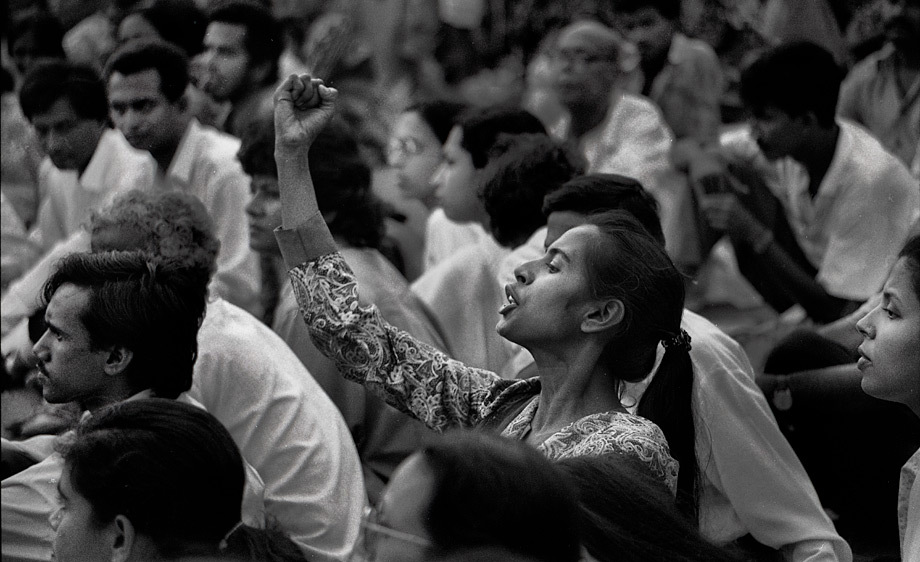

From A Struggle for Democracy, 1987–1990

No heaven, no hell, no everafter, do I care for when I’m gone

Peace here I seek, in this sand and soil, this place where I was born

As oceans deep, as deserts wide, as forests and fences loom

As children die, as lovers sigh, no cross, no epitaph, no tomb…

Place by Shahidul Alam, 2017*

Paddy fields at twilight captured in technicolour stretch to the periphery where they meet restless, silhouetted trees. This is where a border separates two nations. Partitioned in the last century by colonial powers wherein families were atomised, exiled and many rendered homeless – the consequences of which still resonate today – this serene image exudes with traces of contested histories, suspended in an otherworldly, hyper-real atmosphere. At first glance, the fields are lush, unrelenting and fertile – the land of plenty. But there are truths that lie embedded within the image, within the homeland – maybe even the nation – as un-truths begin to blur into focus between meadow and sky. Beyond the fields towards the margin, in the clearing nearby, or in cottages out of view – hidden lives covet hidden truths that are brought to a frontier every day, to a threshold they must transcend in order to make it through. Such is the power of Shahidul Alam’s message and the reality it slowly unsheathes.

This image was drawn from a forceful and provocative exhibition titled Crossfire, mounted in 2010 and curated by the Peruvian curator, Jorge Villacorta, but was soon closed down in Dhaka upon a government ban (later shown at the Queens Museum in NY, 2012) as the subject dealt with heavy-handedness of the state highlighting extra judicial disappearances that have been rampant statewide, if not region-wide – a brazen reminder of our own geo-political reality. It was however, reopened to the public upon legal recourse, guiding them once more through the open fields, strewn vestments, near abandoned lanes, edgy graffiti and eventually the shrouded bodies, readied for autopsy and dissection. The images echo with eclipsed voices – recorded disappearances that found presence once more through memory-traces and material evidence. The site in question was of an alleged shootout; the victim, it is believed carefully planted in the grass given there was no other disturbance to the site.

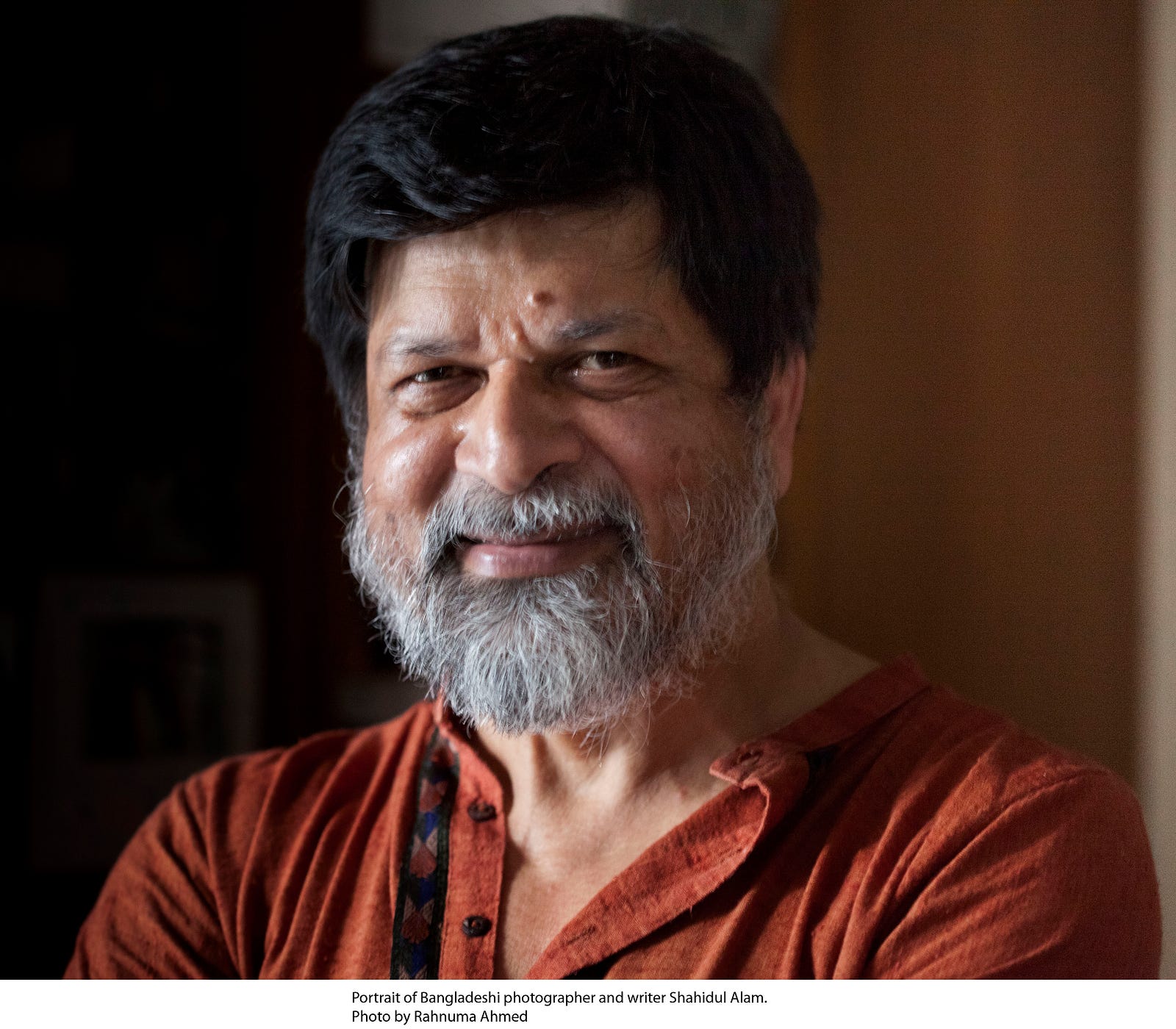

As a colossal figure who has worked ceaselessly for the last three decades as a practitioner, publisher, writer, pedagogue and activist – countering rote opinions, opposing covert and guided elisions of secular expression, revealing marginalizations and atrocities within community, Shahidul Alam – now seeks justice yet again in a personal capacity, having been reprimanded by the state for voicing his reactions to civil injustices being championed by students who have mobilized in the thousands across Bangladesh over the last few days. As the Founder of Drik Picture Library in 1998 and subsequently Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, he went on to set up Chobi Mela, South Asia’s most influential photography festival. Which is to say, there is a dynamic, poetic and prophetic power in this moment too as Shahidul has over the years, galvanised the passionate inflections of an entire generation to think critically; to see well beyond the surface of an image (or circumstance) and to always question event, intention, context and voice (of the self and other). Having probed and exposed homogenizing tendencies across social spectrums by cross-examining cultures in conflict, he has championed the individual as an unwavering, energised force – and personal disclosure as a profound political tool.

*…As bullets whiz by, as shrapnel shard, as hate pours from above

As blue skies curse, the wounded I nurse, as spite replaces love

It is home I long, as I boundaries cross, a shelter that I seek

A world for us all, white brown short tall, the boisterous and the meek…

From Women of the Naxalite Movement

At a time when political pogroms surrounding identity issues seem force the world into binaries yet again; as religion/caste or class in coded and overt ways enforce xenophobic insecurities or induce a depraved form of ritual cleansing – his life clearly denounces a growing societal malaise by speaking to and of vibrant lived testimonies which function as counter-arguments, making transparent rampant authoritative motives. Joining a chorus of articulations in the arts field, his work activates a sense of multi-culturalism that is carefully and poignantly deployed as a parallel dimension through mounted international exhibitions – be they series like Women of the Naxalite Movement and Everyday Life in Bangladesh, to publications such as Birth Pangs of the Nation or My Journey as a Witness. A head-on debate with notions of sovereignty, authenticity, and extendedly, even civilization then become ways in which trans-national issues are tackled with a symbolic energy.

*…If my bosom is raised, or my beard is long, or I sleep with the ‘wrong’ kind

If my politics isn’t yours, nor my country of birth, a terrorist you will find

You return my boat to the cruel sea, back to the wars you wrought

Walls you will raise, to keep me at bay, my children in danger fraught…

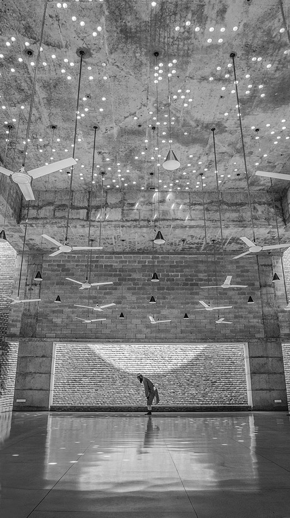

From Embracing the other, 2017

From Embracing the other, 2017

In 2017, Shahidul presented Embracing the Other, looking at ways in which we can re-calibrate the debate on radical Islam by considering the everyday life of devotees, focussing on one particular centre of learning, the Bait Ur Rouf mosque. In his words, “What I want to do through this work is to establish that Islam (and pretty much all religions) by and large, provides a moral compass for our navigation. There are large magnets around that have changed the direction of our compass. I want to return to the original direction and to remind people that it is the carriers of these magnets both within, and outside, whom we need to challenge. It is not Islam we need to fear, but the weapons industry and those who control it.”

To engage with a global debate by questioning stereotypes through the exposure of local histories and personal narratives, has been a constant and provocative refrain in his work so as to examine tolerance in contemporary South Asia. His photography and his poetry present interlinked and lyrical propositions for the need for fusions – at a societal level by using visual reminders and metaphors around appropriation and occupation. It is this very ethics of discontentment – ideological affinities and strategies resulting from constitutional stalemates, that he emphatically deploys for bearing witness at ‘home’ – even his own home from where he was forcefully and secretly captured by the authorities. It brings to light, in a resounding way, constitutional loopholes for those in power to mobilise laws such as section 57 of Bangladesh’s Information Communications Technology Act, which has seen several citizens and media practitioners incarcerated over the years; and makes us demand more emphatically, a world without dark, outdated constitutional clauses such as section 124A (IPC) or 57 (mentioned above), but perhaps more keenly observe 19(1), which enumerates our fundamental right to express freely, and to create new lands and territories unencumbered by hateful pasts.

But it also brings into focus an earlier exhibition he produced in 1987, titled A Struggle for Democracy, which speaks of the pangs of a nation on the precipice of change; of the death of Nur Hossain which led to free elections in 1991 – yet terror, genocide, civil unrest, and the subsequent devastation and uprooting of entire communities continues to unfold. And while many stories of suffering are simply never told, his work preempts a new wave around the iconography of activism – the production of fresh visual testimonials through the fearless inscription of injustices as his own students are now everywhere, and his institutions stand strong.

And so our thoughts too remain with Shahidul who has shown us, once again through his own predicament, the brutal erasures and agonized absences that are being imprinted on the collective memory of a people – everywhere.

Kalpana’s Warriors, 2016

And through his thesaurus of clues we find evidence of other lives that must funnel our undivided attention: such as Kalpana, who was only 23 when she was abducted, after making her life’s mission to campaign for the rights of the indigenous people living in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), on whom Shahidul mounted an exhibition in 2016 using laser etching on straw mats. But as he continues to suggest, these etchings are not only to be reflected in our minds eye, but in other places too…

*…I love the land I was born in, the tree that gave me shade

My broken home, my shattered dreams, slain lover that goodbye bade

My slanted eyes, my dreadlock hair, my tongue though strange may be

I bleed red blood, as flows in your vein, Is there a place in your heart for me?

The police detention and alleged beating of photographer Shahidul Alam is a shocking development in Bangladesh. The videos circulating online show him unable to walk. We, the photography and activist community in India, strongly condemn this action and call on the Bangladesh government and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to release him immediately. It needs no saying that Shahidul is a pillar of not just Bangladeshi photography, but of the world photographic community. As a concerned photographer, he has stood for human rights for decades and has used his medium in the most engaged way to fight this fight. He has placed South Asia and Dhaka in particular, in the center of international photography through his advocacy of non mainstream photo cultures through his Drik agency, school and festival in Dhaka.

The attacks on photographers and journalists in Dhaka are an sharp wake-up call to us in India, where journalists are being fired from print and television channels for doing their job and questioning the ruling government on policy failures. Like us, Bangladesh calls itself a democracy, but no democracy is legitimate without protection of freedom of speech and specially a free press. We must stand together to resist all attempts to curb our voices.

The world is with you Shahidul!

—Ram Rahman, Photographer and activist

It’s a cliche – too casually deployed – to call someone an institution. But Shahidul Alam is at least three. Drik and Pathshala of course. But the most important of the three would have to be the man himself.

Generous. Courageous. Visionary. Shahidul has dedicated his life to improving the world we find ourselves in. His belief in the transformative power of visual culture, and in the young to enact such transformations is unparalleled. We need him back. Now!

—Hammad Nasar, Curator

Shahidul has taught us how to dream, to love, to fight injustice. Photography is just a tool, we should take whatever medium is necessary and to tell the story we need to. Until we push these boundaries inside and outside, from all peripheries, we will never reach a point. One Shahidul means voice of thousands. He is the symbol of uncompromising strength.

— Munem Wasif, Photographer

As someone who has given so much of his life not only to the community in Bangladesh but also far beyond including India, it is time now for us to step up for Shahidul.

—Sohrab Hura, Photographer

Shahidul Alam is an inspiration to everyone who considers light and the lens to be instruments of reflection. He is not just a very significant photographer, but also a teacher and mentor to several generations of people working with the photographic image all across South Asia and in many parts of the world. That he should be incarcerated, harassed and tortured for doing his job – using his vision, critical intelligence and compassion to draw attention to the just demands of young people in Bangladesh is nothing short of a scandal. That this should be done by a dispensation in Bangladesh that swears by democratic and secular values is even more shameful. I hope that Shahidul Alam is released soon and can go back to his work, his life, his teaching and the making of images.

—Shuddhabrata Sengupta, Artist, Raqs Media Collective

He is one of the most important photographers of our time and his commitment to working towards a better and more just world for all is inspirational. It is my hope that justice and sense prevails and that he is released immediately and unconditionally without charge and is allowed to return to his family and his valuable work.

—Dr Mark Sealy, Curator

I am shocked and angered by the news of Shahidul Alam being forcibly confined by the Detective Branch in Dhaka on Sunday. Shahidul’s only ‘crime’ were some FB posts and an interview to a news channel speaking in support of an agitation by young students in Bangladesh demanding a safe public space and more accountability for rash driving on the roads. The infamous ICT act has been used to silence the voices of those like him who speak up against the authority of the state. The FIR states that his remarks will worsen the law and order situation and ‘tarnish the image’ of the country. However, Shahidul’s illegal detention is only one among a series of acts that have already tarnished the image of Bangladesh that include attacks and murders of secular and atheist writers, bloggers, and publishers as well as sexual and religious minorities. Even while we condemn his incarceration in the strongest terms, it is important to remember that the abuse of human rights and democracy is a feature of the region as a whole and that many more like Shahidul Alam must speak up against these violations in India as well.

—Sabeena Gadihoke, Professor, AJK Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia

One of the most shocking images from the aftermath of Shahidul Alam’s abduction from his home by the Detective Branch of Bangladesh is one in which he is being half-carried and half-dragged by a large posse of policemen. Disheveled and barefoot, he looks at the camera and says: “I have been assaulted. They have washed my blood-stained ‘panjabi’ (kurta} and made me wear it.” That one of the most respected citizens of Bangladesh and an internationally reputed cultural practitioner should be treated like a criminal in his own country is a matter of shame for not just the government – because those in power tend to be shameless – but all those who have remained silent through the Awami League’s continual violation of human rights and civil liberties.

When in 1996, after two and a half decades of authoritarian rule, the daughter of Sheikh Mujib led the Awami League to power, it was hoped that finally the winds of change and freedom would sweep across the country. Sheikh Hasina promised to return to Bangladesh, the secular and democratic impulse of the Liberation War suppressed by the militaristic regimes following the the assassination of Sheikh Mujib in 1975. At the start, such an aspiration, even seemed possible till gradually the Awami League began to take the shape of the beast it had sworn to replace. Just as the current BJP Government in India fends off all criticism as the rantings of anti-nationalists, the Hasina government has reduced the legacy of the Liberation war into a blunt instrument with which to bludgeon dissent. The tragedy and irony is that the Awami League is bludgeoning those who kept the cultural memory of the Liberation War alive with a generation that voted Awami League to power in 1996 and then 2009.

Cultural memories are never preserved by political parties driven by electoral aspirations but individuals, groups and communities. Shahiidul Alam is one such extraordinary individual. Not only has the Drik Photo Library archived the many histories of post-Liberation Bangladesh, it mounted in 2000, the historic 1971: The War We Forgot exhibition that Shahidul curated for the first edition of ‘Chobi Mela’, the Festival of Photography in Asia. Over six years, Shahidul had travelled across the world to painstakingly identify and collect images that would comprise the exhibition. In addition to photographs taken by local photographers, the exhibition included images of 1971 taken by internationally renowned photographers and photojournalists like David Burnett, Mary Ellen Mark, Don McCullin and Raghu Rai. The exhibition educated an entire generation about the Liberation War and reminded others, both within and outside Bangladesh, about one of the most under-discussed genocidal wars of the the 20th Century.

But Shahidul’s curation was not a paean to blind nationalism which is why the government asked him to take down the images that showed Bengalis killing alleged (Urdu-speaking) collaborators. Instead, Shahidul pulled-off the the exhibition from the gallery in the National Museum and moved it to Drik. He was admired for his principled act of defiance. Today, for a similar act of ethical dissent he is being detained and tortured to be tried under the draconian provisions of section 57 of the ICT Act and face up to 14 years of imprisonment. (Section 57 is similar to 66A of the IT Act that the Supreme Court of India struck down in March 2015 on grounds that it would have curbed Freedom of Speech and Expression and created a ‘chilling effect’.)

The Detective Branch has accused Shahidul of spreading “fear and panic” using “fantastical and provocative lies”. On the contrary, in supporting the road safety agitation of thousands of school children, Shahidul Alam has acted once again, as an outspoken conscience-keeper of Bangladesh. Over two hundred students have been maimed and injured by the rubber bullets that the government has used to quell the agitation. Can there be any doubt who the real enemies of the people are?

It is very possible that the ‘system’ will collude to keep Shahidul incarcerated. It is possible that evidence will be fabricated and others arrested and detained as `collaborators’. This mode of silencing critics and creating a `chilling effect’ is a contemporary South Asian nightmare which includes India.

Therefore, in fighting for Shahidul Alam, we fight for ourselves. We fight to preserve those critical spaces where democracy lives and breathes.

—Shohini Ghosh, Professor, AJK Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia

Comments