Visual archives as a metaphor of Time

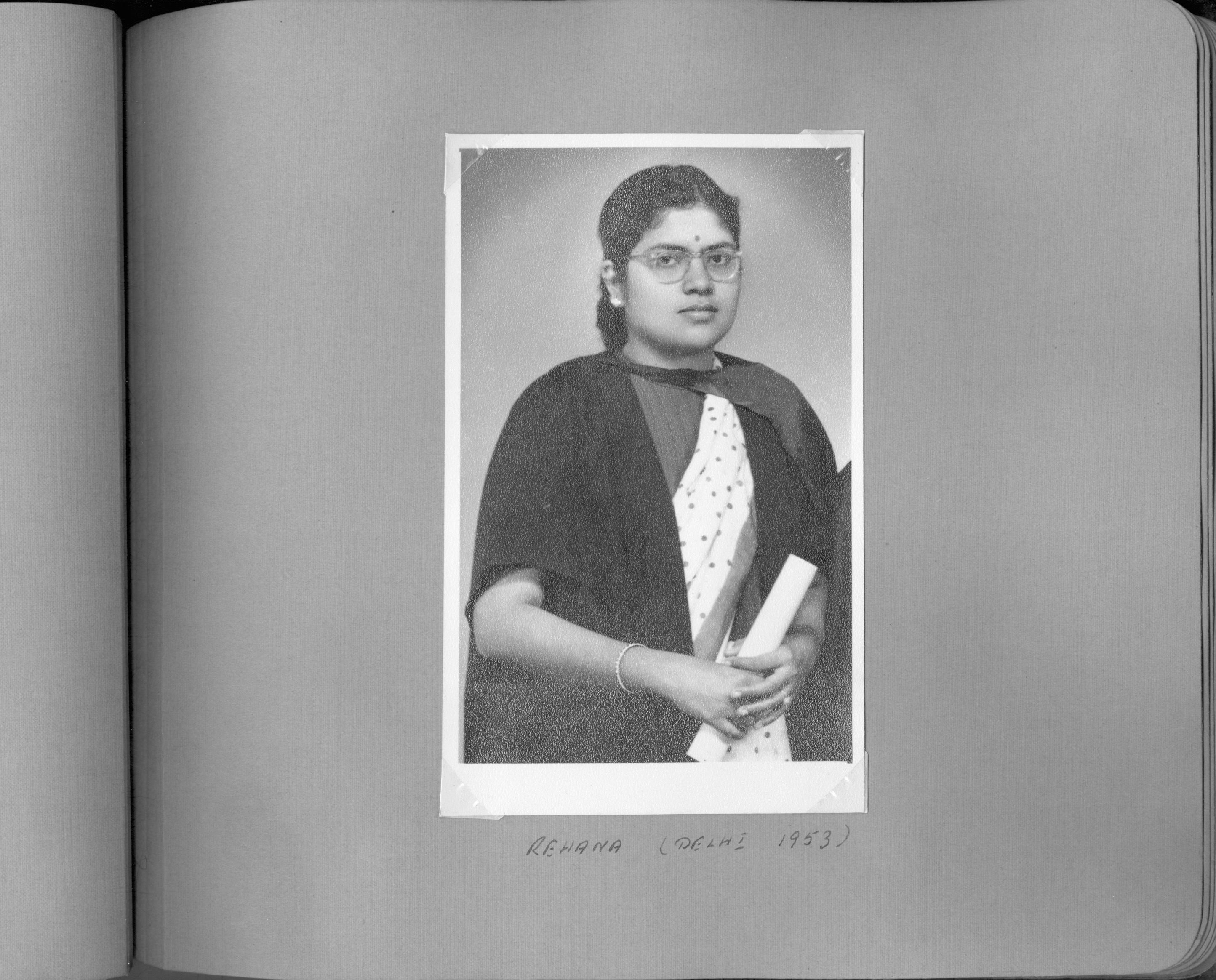

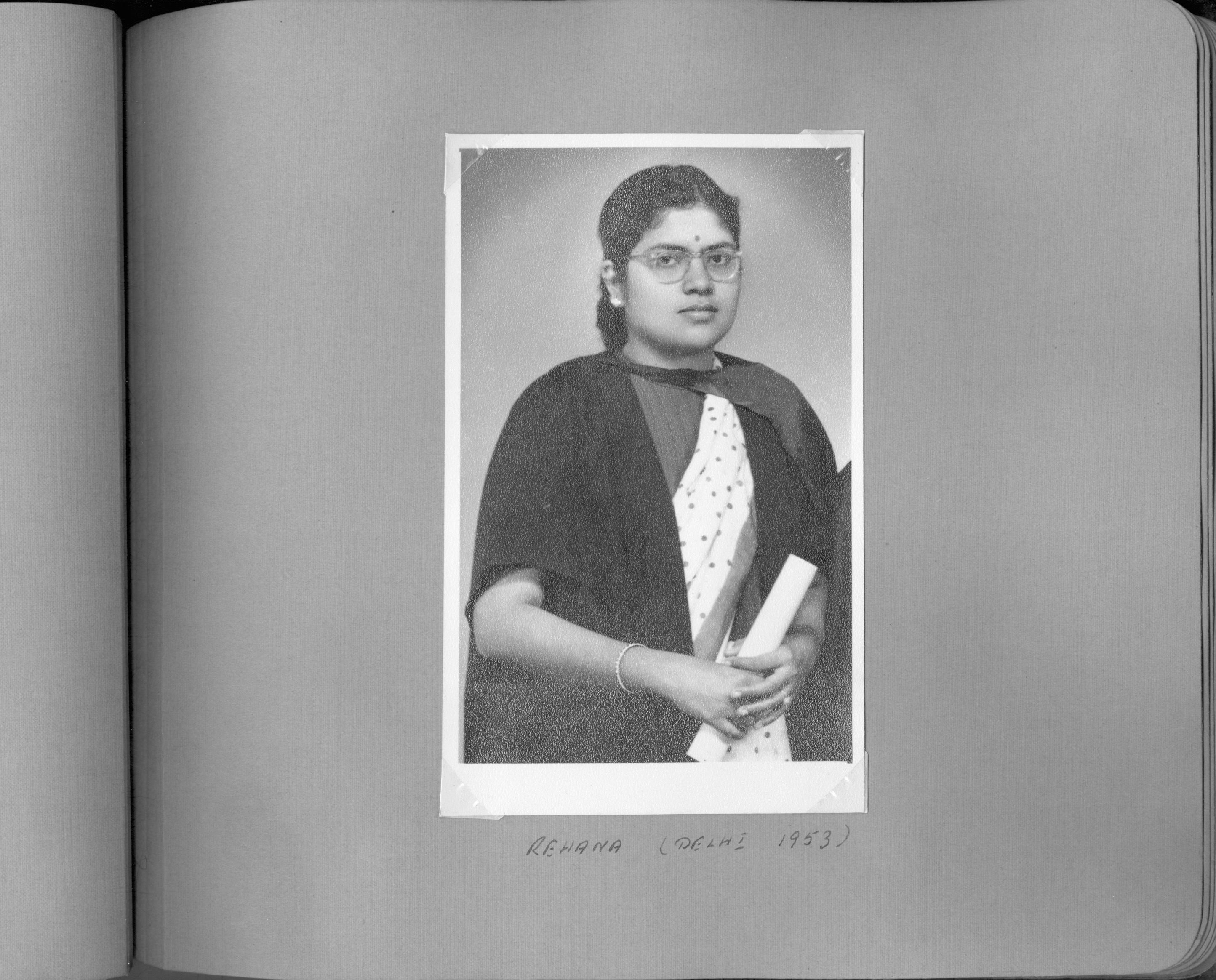

Dr. Rehana Bashir’s graduation portrait, 1953, Bashir Family Collection

[Family albums’] meanings are social as well as personal – and the social influences the personal. Family photographs are shaped by the public conventions of the image and rely on a public technology which is widely available. — Holland, Patricia., Spence, Jo., Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography

The notion that images and their associated memories lie at the ‘heart of a radiating web’ of connections leading to reflections about location and interpretations about the past, are aspects that emanate from British author, Annette Kuhn’s seminal work, Family Secrets (pub.1995). Though her references are to personal photographs and compilations which may have never been shared previously, she insists that associations formed through them, move beyond the strictly personal—rather they link the historical, cultural, and social with it.

Her argument further purports that the process of ‘memory-work’ and family photographs, including other mnemonic sources, is mired with inevitable distortions of the past and unforeseen yet enforced amnesias. The author therefore acknowledges that the stories that emerge from visual interactions or interplays are neither out-of-the-ordinary nor ‘factual’ anomalies. They are unique compositions. This contention provokes the question: What particular aspect of history do we garner from family photography?

Family photographs, either explored through one’s own archive or through an unknown provenance—migrating from a private zone to the public sphere by endorsement or chance—have provided essential clues about the larger narrative history of community, ethnicity and nation. Online storehouses such as the Indian Memory Project or the Nepal Picture Library among others, have honed their own anthropological perspectives through freewheeling and insightful investigations into the undocumented histories of the subcontinent with images that are not always produced by or even presented by known archives or institutions, thereby generating timelines and cross references that may never be registered in larger, mainstream establishments, but from the repositories stacked in every home.

As with Sohail Akbar’s exploration of his own family album here—through the authorship and narrative construction of his mother, Rehana Bashir, the images offer the reader (in this case also Sohail), an opportunity to understand the self through the experiences of his family members. While the images themselves act as references to events and important family occasions, they intermittently comment on aspects of their own creation—the photographic practice at the time, or the political and social environment which conditioned their production.

Akbar’s reading of the ordinary and routine images of his mother’s album also attempt to paint a particular portrait of the traditions and practices of a middle-class family at a very critical, pre-and-post Independence moment—who identified themselves as ‘Indo-Persian Muslims’, which till this day echoes with a status that has not entirely undergone a paradigm shift, at least in civil terms. As a consequence, images of that moment can be read as interventions around a relatively undocumented social and cultural history, forging a unique timeline and sequence, yet signifying a larger social condition and impact.

Below, excerpts from Akbar’s unpublished essay, highlight key events in Rehana’s life as an independent woman of ‘modern’ India, which also visually present changes in the practice of photography. Perhaps what can be said of the current form of the album, amalgamated over time and through the participation of many members of the family, is this:

In this marriage of sociology and social history, the typicality of the album is often stressed as a function of its collective authorship – compilation by agreement, rather than individual authorship.—Langford, Martha. ‘Speaking the Album: An Application of the Oral-Photographic Framework’ Locating Memory: Photographic Acts

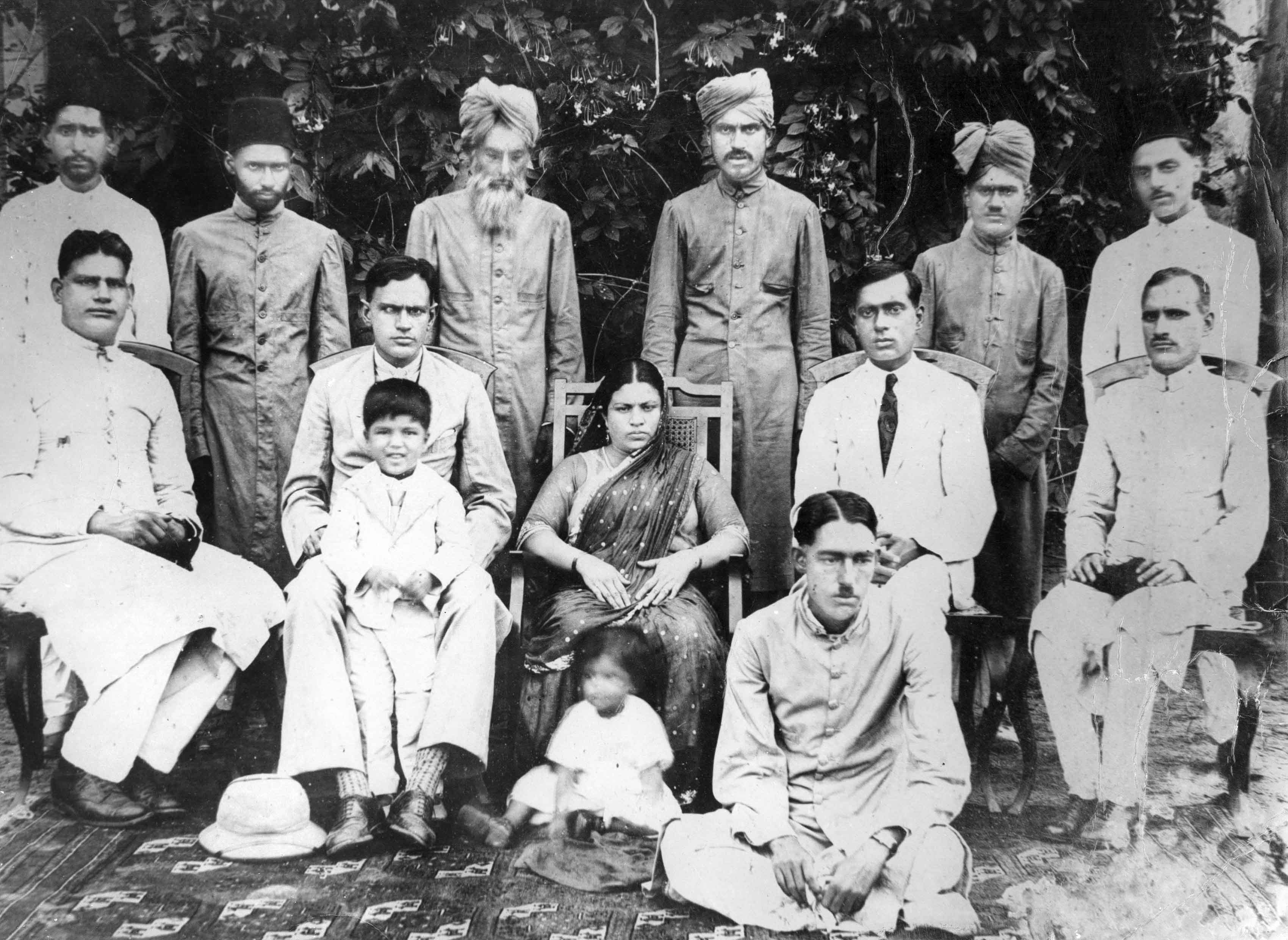

Prof Bashiruddin, his wife and children with the staff of the Aligarh Muslim University library’, 1932, Rehana Bashir Collection

My mother’s generation was truly India’s post-Independence, first generation. Even though they were born in British India, they were soon unshackled from it.

The story of my mother in this album begins with a very eminent and amusing picture—she is there and she is not there.

The image in question, seen above, has two toddlers in the foreground—one sitting on the floor and the other standing. The image of the boy is clear and I can make out that it is my mother’s elder brother, who was about five years old. The child who appears as a blur next to him is the two year old Rehana, my mother—fidgety and restless, she can’t keep still on the floor and is thus registered in movement on the film. The year would have been 1932 or thereabouts as she was born in 1930. I consider this photograph to be the earliest representation of the Bashir family with the youngest child, yet to be born.

The picture tells us many things about the people who are central to the story I am attempting to disclose. I, who will be born almost thirty-five years later and shall get to know my maternal grandfather, Prof. Bashiruddin, am struck mainly by his sartorial sense.

My grandfather was always seen in western attire, whereas in this picture, around him are other members who adorn the traditional Indian shervani. His mannerisms too were very British, which very early, earned him the soubriquet—Kala Angrez or Black Englishman. He was a person truly affected by western modernity—reflected also in his general outlook. No wonder you see his wife in the same picture seated amongst a crowd of men! This is because he rejected the practice of purdah (veiling) and always believed that women were to be treated no differently.

Bashir Family Home

Bashir family home, 1930s, Rehana Bashir Collection

Bashir family home, 1930s, Rehana Bashir Collection

My grandfather’s progressive standpoint was also articulated and captured in his pictures of the house that he built. In the latter half of the 1930s, the family moved into a new residence that was conceived of and constructed by him—located on the outskirts of the university campus. At a time when the contemporary architecture of Aligarh had all the moorings of the Indo-Persian style—arches and domes formed a prominent part of the cityscape—it is nothing less than amazing to see a house that completely stood apart from the norm.

With clean and straight lines, the mansion sports a minimalist look, reminiscent of the refined architectural lexicon of Joseph Allen Stein, or even Charles Correa, among other modern professionals. Blocks of rectangular shapes are placed on one another—a marked rejection of curves and frills, which were however used to stunning effect by other architects in time such as BV Doshi, Laurie Baker and even Claude Batley. Asif Bashir, the youngest of the three Bashir children recalls that the architect was from Hyderabad, a city quite far from Aligarh, but a bastion of modernism at the time.

Early Childhood (1930–1940)

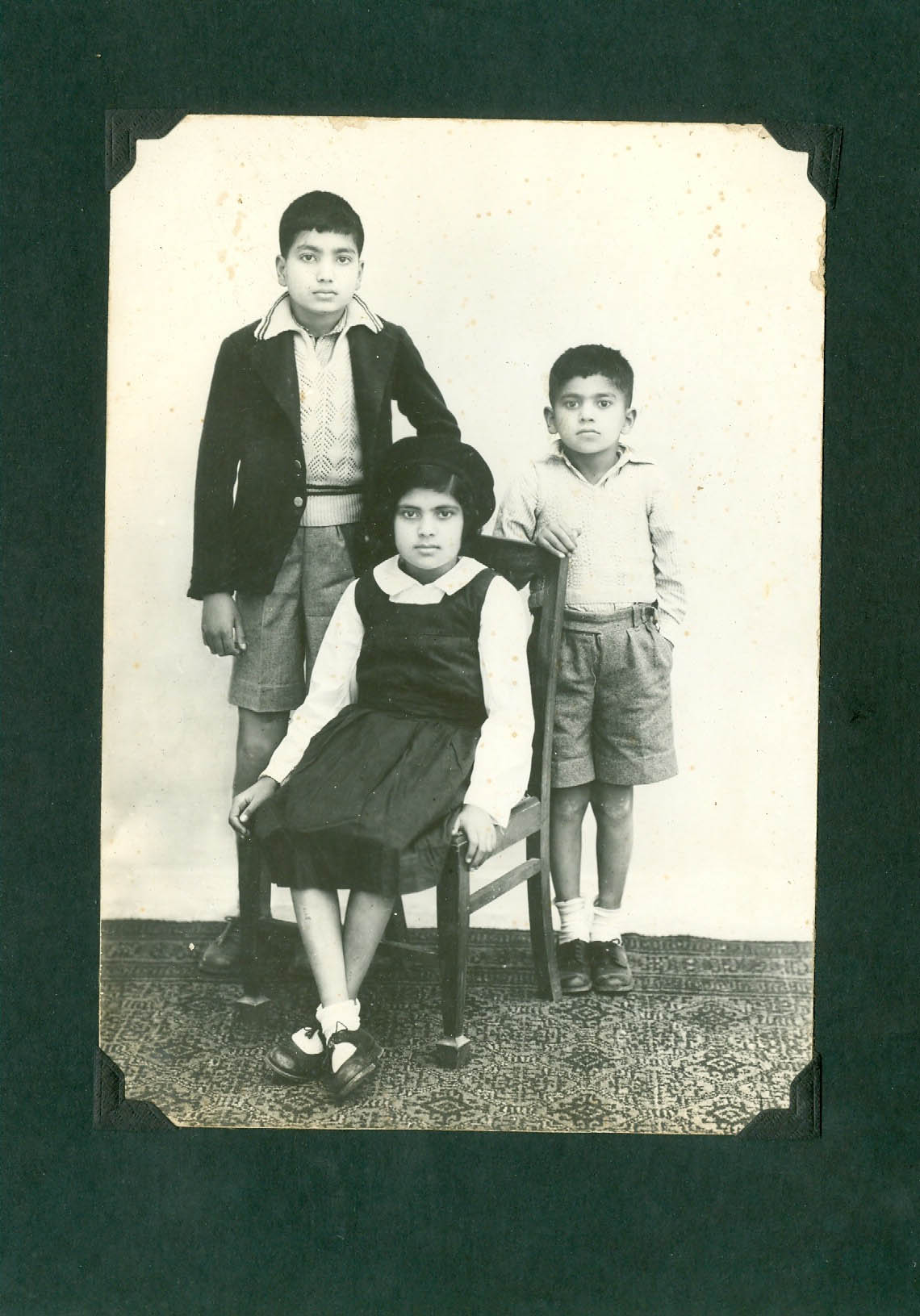

Arif, Rehana and Asif Bashir, early 1940s, Rehana Bashir Collection

The album folio above opens a rather intriguing window onto my mother’s life. It is also the first picture that marks the presence of the youngest of three siblings, Asif Bashir.

My mother seated in the centre may be wearing her school uniform—but upon scrutinising it further, it appears as though she is adorning a stylish headgear, possibly a beret. My grandparents, in time, would support a superior education for their daughter. She was sent to the best convent in the state which was in Allahabad, more than three hundred miles away from Aligarh, and from thereon, she would only advance further into her medical career.

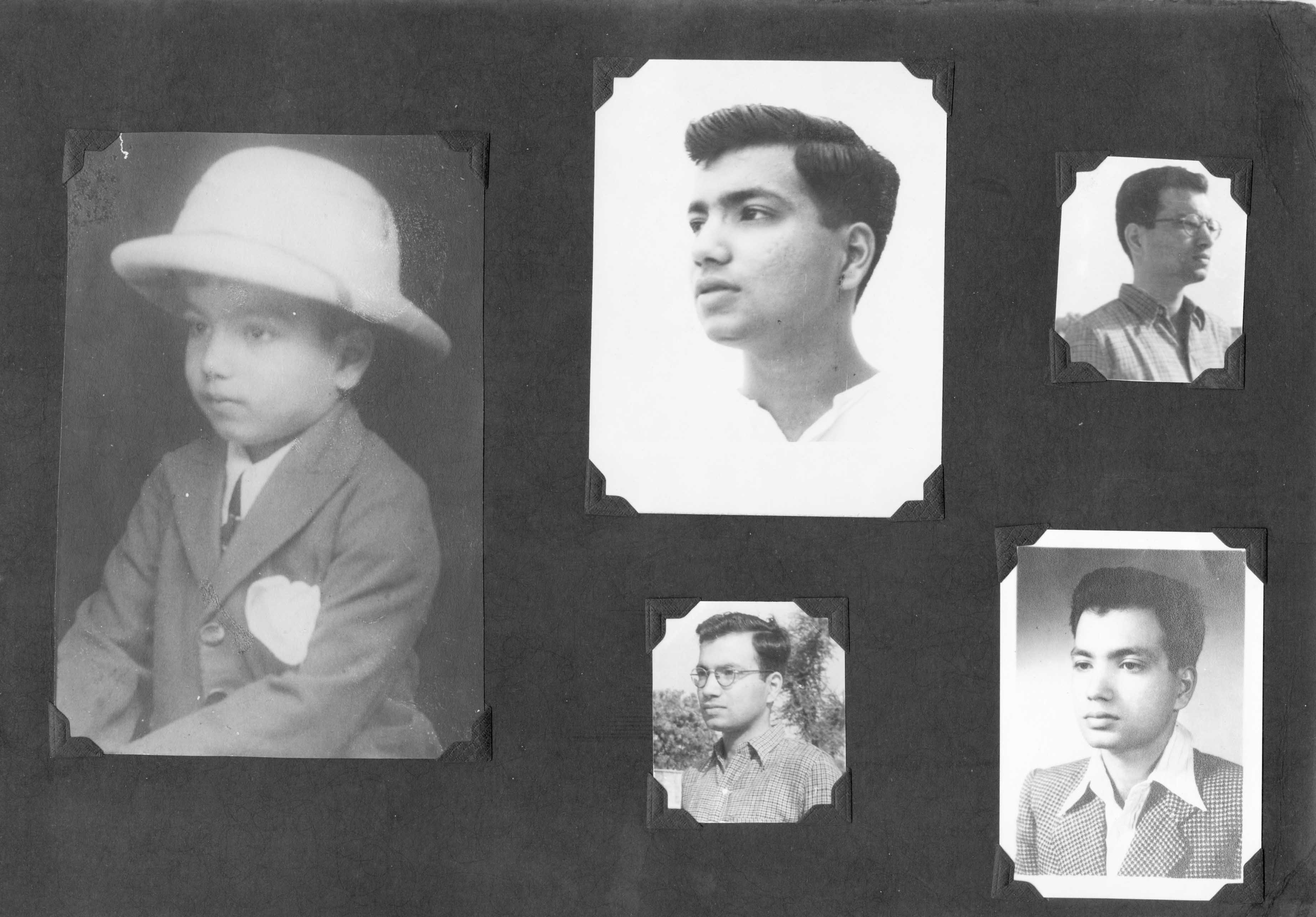

Arif Bashir, 1930–1940, Rehana Bashir Collection

The story of my mother’s early life in pictures however, cannot be complete without mention of her elder brother, Arif Bashir. Arif being the first born was the most photographed of the three siblings. He was captured in different western attires over time, often even in the studio. A most adorable profile image of his, donning a Sola hat and wearing a coat and tie, was to later become an enduring, signature-style sartorial convention. Needless to say that he grew up to be a person quite obsessed with his own looks, complexion and attire!

Delhi (1950s)

Album folio with photographs from Delhi, 1950s, Rehana Bashir Collection

The post-Partition, communally-charged atmosphere was not safe either. Muslim families in India were plummeted into insecurity in the aftermath of the riots. The most vivid memory that Rehana recalls from those times was of living at a family friend’s house when she had gone to Delhi for admission. It was located around Chandni Chowk, dominated by a Muslim populace, and a barbed wire fence was stretched all around its periphery and electrified as live wire in the nights; allegedly done to ward off marauders who may want to attack the community. A night curfew and patrol was also instituted so as to protect people from any untoward incidents. But at the same time, the community was hemmed in, caged.

There is a visible shift in the albums’ photographs from here on. The sari, for instance, prominently enters the frame—a shift that will forever become as much a statement as a motif in her life. While the earlier images portray a so-called provincial, small-town life with family and friends, the photographs from this period show groups of friends that have crossed the threshold of adolescence and stepped into a life that is independent of home. The shalwar or gharara clad teenagers gradually become self-confident, sari-clad women who would boldly face the camera in a studio along with, as we can see above, two classmates who had, like her, come to Delhi from distant, smaller towns.

A visible marker of perceived cosmopolitanism like the bindi which is traditionally not worn by Muslims in North India, was now forthrightly worn. With pride and as a mark of syncretism, this probably was a cultural influence imbibed from the new friends that she made.

Allahabad (1953–1957)

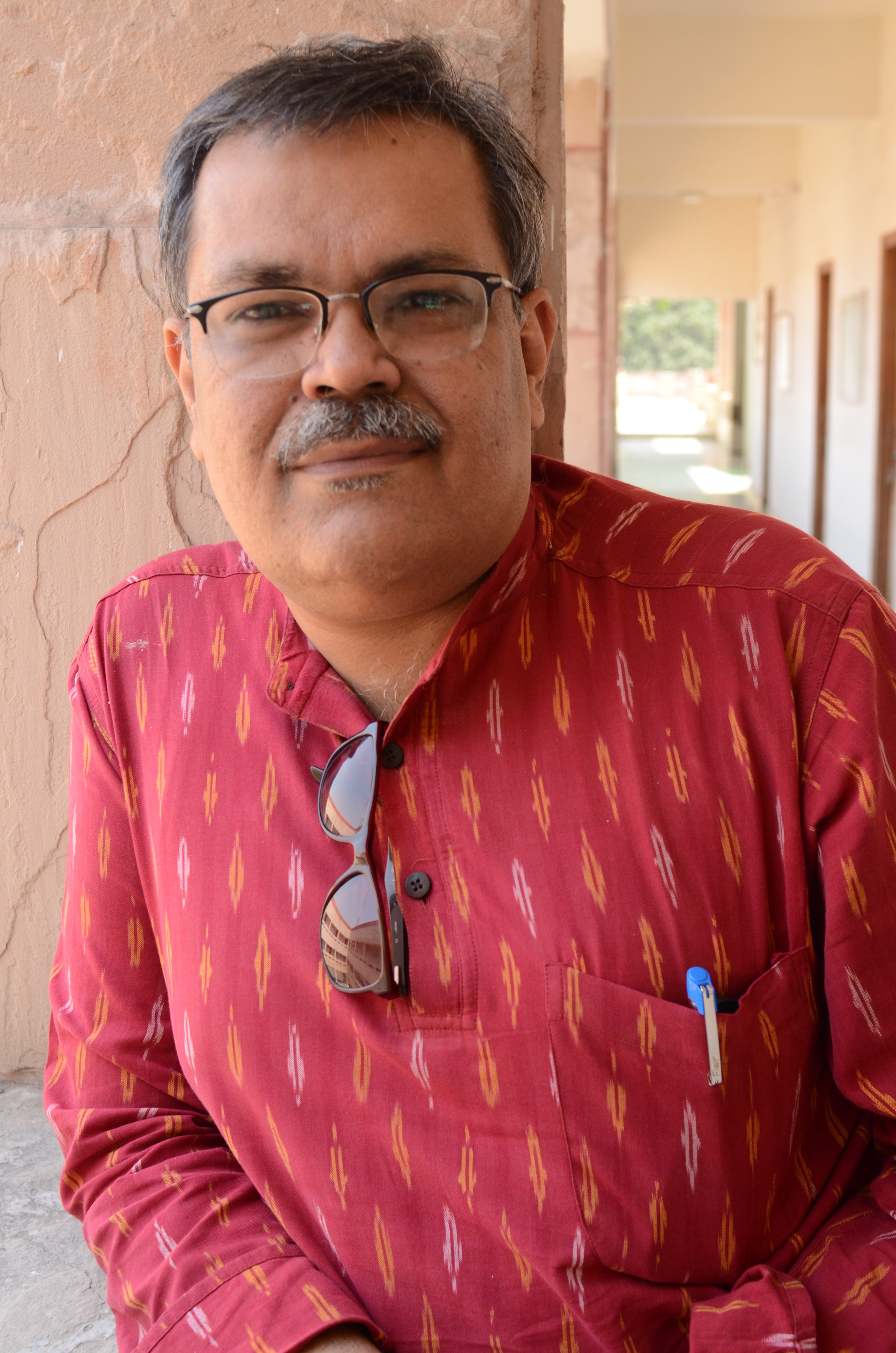

Graduation portrait, 1953, Rehana Bashir Collection

In 1953, Rehana posed for her graduation portrait in a Delhi studio. She was now a qualified doctor. With a Medical degree in her hand at twenty three years of age, donning the black gown—an image of self-contentment if not well-deserved achievement.

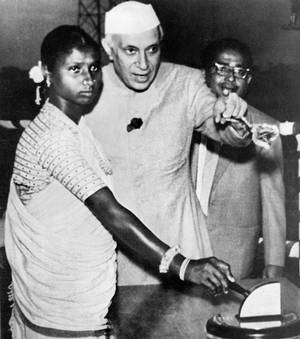

India had just arisen to a new dawn and Jawaharlal Nehru, its first Prime Minister had the support of the people to make the country that had suffered years of colonial rule, a modern nation in a new globalised world order—and, according to him, a scientific bent would deliver this dream. Planning to build factories, dams, roads, institutions etc. that would facilitate the life of the common man and enhance the self image of the nation—were in full swing. Nehru who was a socialist at heart wanted to provide equal opportunities to all. His iconic photograph of getting the power station at a dam inaugurated by an Adivasi woman construction worker spoke resoundingly of his commitment.

Budhni Mejhan inaugurating the power station at the Panchet dam in December 1959, Nehru Memorial Museum And Library, New Delhi

Rehana’s first job was with the Kamla Nehru Memorial Hospital in Allahabad. She had no clue that after having studied in a convent school for three years she was destined to return to this city which was going to become her home for the rest of her life, although there would be another minor deviation before such a permanent settlement occurred.

Nehru inaugurating the Maulana Azad library with Prof. Bashiruddin, 1960, Rehana Bashir Collection

Prof. Bashiruddin, Rehana’s father, was in any event, well settled in the city, and among other fortes, was a pioneer librarian. He established the library Science department at Aligarh Muslim University and also authorised its famous Maulana Azad Library.

Allahabad (1953–1957)

When Rehana graduated from the Medical School, she was subsequently on the lookout for a place to work. She then met Prof. Dastur from Allahabad University who was visiting Aligarh and was a guest of Rehana’s father. My mother mentioned Kamla Nehru Memorial Hospital to Prof. Dastur and her desire to work there, at which point he told her that he knew its Director, Dr. Vatsala Samant well and would put in a good word.

Dr. Vatsala Samant soon offered her the job and she was to become Rehana’s mentor and guide in her medical profession. As this was a hospital for women there was a constant need for women doctors—rare to come by in those days. Dr. Samant was from Bombay and was a dynamic lady whom Nehru had approached and later helped establish the hospital.

At Kamla Nehru she was to grow close to two Maharashtrian ladies—one was Dr. Samant and the other was her deputy, Dr. Sthalekar. It was going to be a fairly solitary life of independent living and hard work, but in a city famous for being India’s intellectual and political capital, there was much to learn and prove.

Dr Sthalekar, 1950s, Rehana Bashir Collection

Dr Sthalekar and Rehana posing in front of the Fiat, 1950s, Rehana Bashir Collection

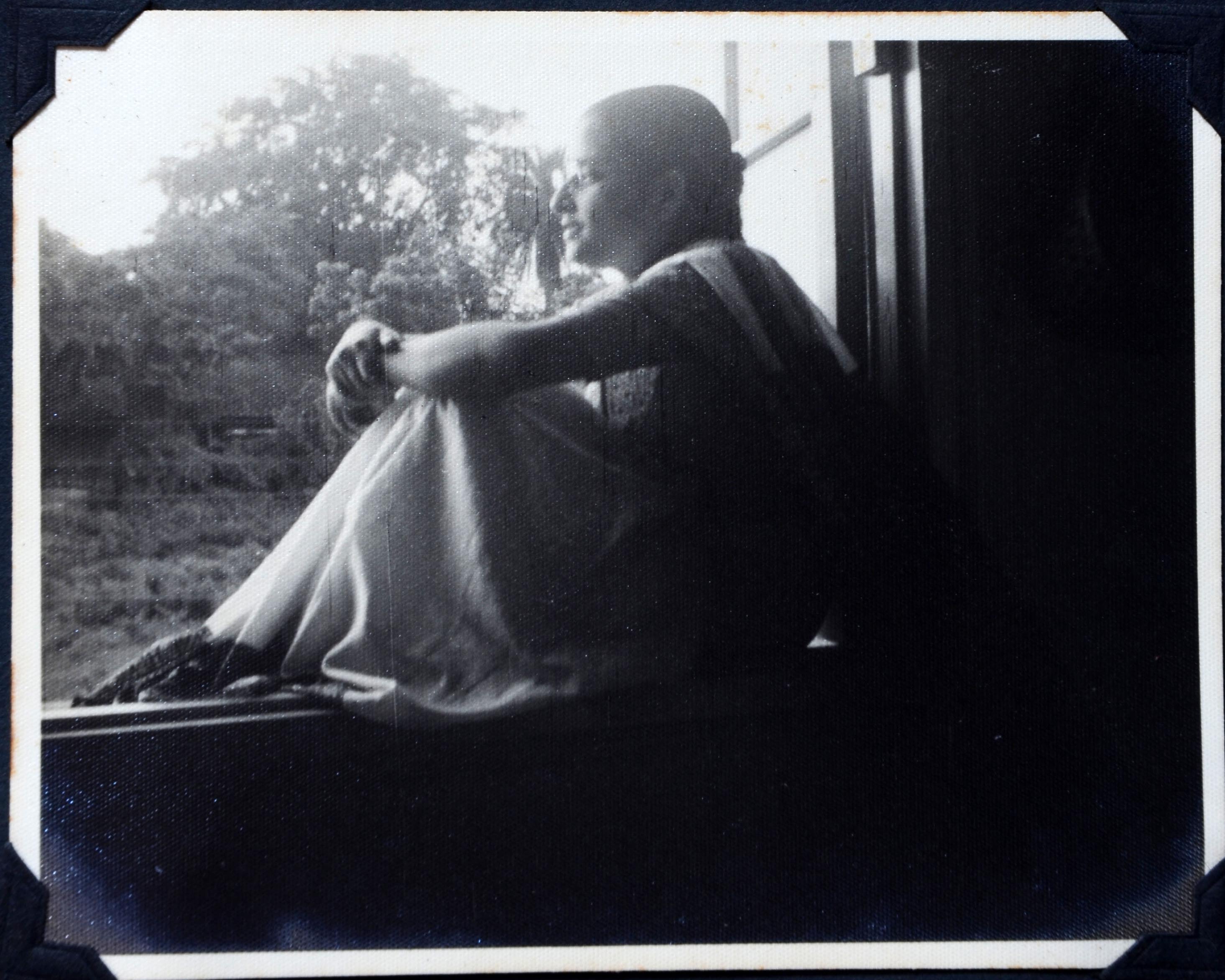

Photographs preserved from this era give us a glimpse into the life of these ladies in their twenties. We either see them in domestic spaces, consciously posing for the camera or get a glimpse of their social life outside the work environment—leisurely outings or picnics to nearby scenic spots of Allahabad.

Dr. Sthalekar was older by ten years to Rehana and had a house in the hospital campus—her mother staying with her. Furthermore, the photos that we see here, give us the glimpse of the amenities of modern day India—a two wheeler, which she rode to work and then a car. In one picture, we see Dr. Sthalekar and Rehana proudly posing in front of Dr. Sthalekar’s Fiat car.

Now looking back, I can sense my mother’s growing influences and aspirations—the need to be an independent woman at the time, wherein she too would own a car and have herself photographed sitting in the driver’s seat in time.

Colleagues from Kamla Nehru Memorial Hospital, 1950s, Rehana Bashir Collection

Dr Prem Pant, 1950s, Rehana Bashir Collection

In another set of photos from this period, we are introduced to two co-doctors whose friendship has lasted till date—Dr. Pushpmalti and Dr. Prem Pant. Along with them, is another friend Rahat, who was not a doctor. Pictures of these ladies, most probably framed by Rehana allude to a life of contentment as an independent professional. Pictures with a staged yet candid sensibility are interesting as a certain cinematic element seems to have crept into the aesthetic which maybe may have been inspired by the film stills that were so popular during the fifties.

Dr. Prem, being a particularly attractive lady, is often the focus of attention in these frames. Soon she would fall in love with a Muslim gentleman and marry him. This would be a big scandal at the time—her parents would temporarily disown their daughter whereas the gentleman would forever leave his family. The friendship with Dr. Prem Naqvi (married name) would be further forged into a family liaison when some thirty years later, her son would marry Rehana’s niece! However, there was another social dimension that needs mention. As it was not easy to arrange a spouse for persons of interfaith marriages in India, relatively fewer people accepted this social manoeuvre and forged such marriage alliances. Luckily, as Dr. Prem knew my mother’s family and was aware of their outlook on such matters, she proposed the family alliance.

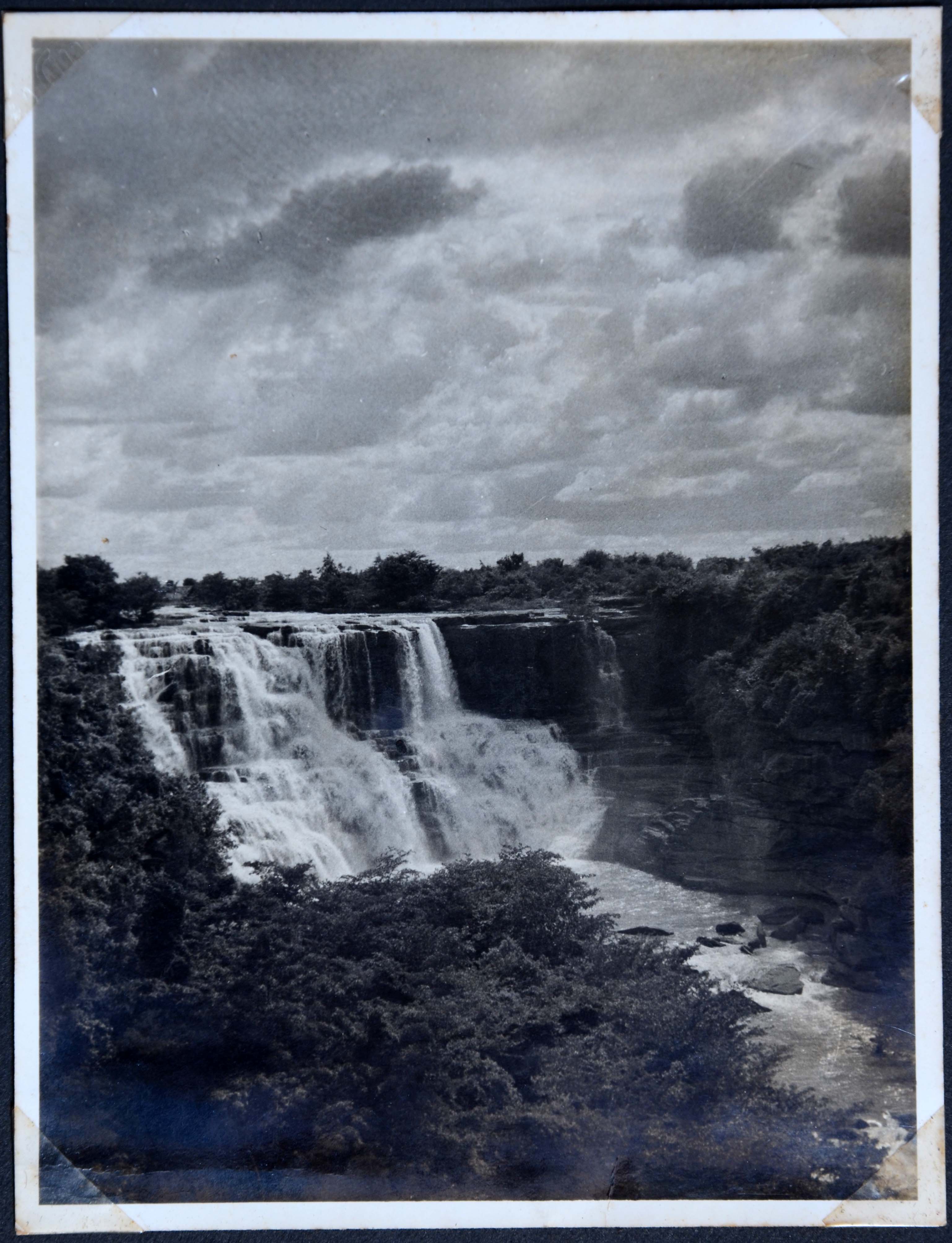

On the other hand, photography of the scenic and its creative interpretation in black and white through an adopted pictorialism is also visible in the album. This aspect is evidence that though professional life kept people busy, routine leisure trips around Allahabad became very common—and their inclusion always takes on a nostalgic sensibility. Waterfalls, riverbanks, places of religious significance etc. were places where these ladies travelled to on Sundays, driving their car on the sparsely populated roads of the expanding countryside. And with them the camera travelled as an essential appendage delivering moments of the exceptional in the everyday. Some photographs of the high-contrast clouds on the waterfront, have a self-evident picturesque quality.

Landscape photography from around Allahabad, 1950s, Rehana Bashir Collection

In another photograph, Dr. Pushpmalti framed leaning against the carved pillar of a Hindu temple catches my attention—the subject’s pose, and the appeal of a waist level camera shot come together to make the photograph balanced and engaging to me. Looking at these images, I cannot stop to think that by now the the work of hobbyists had matured into something more rigorous—wherein the artistic and the evidential merge to form compositions of higher quality.

Dr Pusphamalti, 1950s, Rehana Bashir Collection

England (1957–1959)

The opportunity to hone her skills as a medical professional came in the form of an internship at the Royal Sussex County Hospital in Brighton England, where she would spend close to three years specialising in the field of Gynaecology.

Rehana’s departure to England, 1957, Rehana Bashir Collection

Many people came to see off the twenty seven year old lady embarking on her first journey outside the Indian sub-continent. The picture is a classic airport departure photograph with the person travelling in the centre of the frame surrounded by her companions. Though it does appear that the aeroplane in the background was the same one being taken by Rehana, upon closer look, I read the name on the plane and discovered that it was in fact, a cargo plane, serving only the purpose of a backdrop.

Group photo at Versailles, 1958, Rehana Bashir Collection

Album folio with photographs from around Europe, 1958, Rehana Bashir Collection

Christmas lunch on the ship returning to India, 1959, Rehana Bashir Collection

Looking at pictures of her stay in England I do ponder how a man would have recorded his time there? Would that be any different from a woman’s photographic record?

Wedding (1967)

The two newly wed couples in Karachi, 1965, Rehana Bashir Collection

A friend of Rehana’s, Zarina, introduced her to Zia ul Haq. Zia originally belonged to Allahabad but was settled in Delhi where he was a full-time member of the Communist Party of India and worked as a journalist for the newspaper of his Party.

Rehana herself came from a progressive background where her father had leftist leanings; she was a believer of the inherent goodness that lay in the Communist ideology.

Zia’s entire family had migrated to Pakistan in 1947. Due to his commitment to the freedom struggle, he stayed back in India much against the wishes of his elders. Thus, Partition was a major scar in his personal life.

Rehana and Zia married on January 3, 1965, interestingly in the town of Kota, in Rajasthan. Since, Zia’s parents and siblings were all settled in Karachi, Pakistan, only his father was able to make the journey from Karachi to Kota for his eldest son’s marriage. Thus, Zia and Rehana travelled to Karachi few months after and were introduced to the extended family at the wedding of Zia’s brother, which as they recall, turned out to be a joint wedding reception!

Only three photographs of the Karachi trip are in the album and they give us a peek into the hospitality that the couple received. One of the photos, which is in colour has the two newly wed couples, seated. It is difficult to make out whose wedding it is as both the women are dressed as newly-wed brides.

Sohail Akbar’s childhood (1970s)

Childhood photographs of Sohail Akbar and his brother Sameer, late 1960s, Rehana Bashir Collection

It needs to be said that the craft of arranging the photographs in the photo album was no less creative than the process of clicking the pictures. There is a sequence to the images and at times looking at their arrangement one gets a sense that they may have been clicked bearing their future display in mind. For example, the four photos of the child, one after another are arranged in an undulating format—a kind of stop motion.

I notice that my first three birthdays are documented and I am also photographed cutting the cake. The second birthday cake is in the shape of a Steam Locomotive and I am propped on my grandfather’s lap. My fascination with railways must have sparked before my second birthday as I have a hazy memory of a railway crossing close to our house where my ‘Nana Mian’, my maternal grandfather, would take me to watch the passing trains. No wonder I have always experienced a connect with Apu of Pather Panchali—watching the passing of a steam locomotive in sheer awe.

Sohail Akbar is a teacher of Still Photography at the AJK Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia University New Delhi. Apart from teaching he practices and researches photography. His area of interest includes personal photo albums and family archives. He is also a practicing photographer who has photographed extensively for the development sector in India. He has exhibited in two solo exhibitions in Delhi. ‘Nazraana: A Tribute to Life’ is a Photo Book of his collection of work.

Sohail Akbar lectures and conducts workshops on photography at various institutions in the country and has contributed to the development of curriculum for courses that teach photography at school and university level.

Comments